Note: In a couple of weeks, we will begin a series where the articles will be devoted to answering questions posed by readers. If you have any questions, please click the button below to submit them. If you want your question(s) answered privately, you can mention this in your submission as well. All questions of all levels are welcome.Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Over the past few weeks, we have been reviewing everything we have gone over in this newsletter so far. This method is known as singha-avalokana-nyaya - the method of the Lion’s Backwards Glance.

Yoga is a prescription - a set of methods designed to cure the ailment that we all suffer from - dukkha.

Dukkha is more than just “suffering”, although it is commonly translated in this way. It is the feeling of incompleteness in life - the feeling that nothing in this world will satisfy us completely. The goal of Yoga is complete freedom from suffering, and absolute fulfilment.

Yoga begins with the acknowledgement of dukkha - seeing clearly that nothing we have ever spent our time and energy on has ever resulted in a feeling of complete fulfilment.

This acknowledgement is followed by a decision to make the purpose of your life to overcome dukkha as efficiently as possible. Rather than Dharma, Artha, or Kaama, the purpose of the Yogi’s life is Moksha.

There are four Yogas, and thus far, we have been discussing Raja Yoga - the path of meditation.

Raja Yoga prioritizes direct experience over faith, and uses our day-to-day experience of the Universe to uncover the nature of Self. Given this priority on direct experience, the Yogi must first be able to clearly understand their current experience of the Universe. In order to do this, Yoga provides a series of frameworks to better understand the Universe, the mind, and the movements within it. These are the 25 Tattvas, the 5 Bhumis, the 5 vrittis, and the 5 kleshas.

Once the Yogi is able to discern their experience, practice begins. All the techniques in Yoga share a common, twin, foundation - abhyaas (practice) and vairaagya (letting go).

The foundational techniques come first, and are to practiced in one’s daily life, depending on the situation. The practice of One Thing at a Time - eka-tattva-abhyaas - the six stabilizing techniques, the Brahmavihaaras (ie. the Four Attitudes), and Kriya Yoga, all play different roles in calming the mind and making it conducive to the core of Yoga - the eight limbs.

The eight limbs are a sequential set of techniques that systematically stabilize the various layers of our being.

The first five - Yama (external observances), Niyama (personal conduct), Aasana (posture), Praanaayaam (lengthening the Praana), and Pratyaahaar (sense withdrawal) - are known as the “external limbs.” These are not necessarily seated practices, but things we can do during our daily lives to make the mind more calm, more aware, and more joyful.

The last three - Dhaaranaa (concentration), Dhyaan (meditation), and Samaadhi (meditative absorption) - are known as the “internal limbs”, or simply “samyam”, and are - together - an exclusively seated practice. Samyam is the practice colloquially known today as simply “meditation.”

Last week, we reviewed Dhaaranaa and Dhyaan - going over the fundamentals of the practice, and how to apply them to weaken the kleshas, or mental afflictions. You can find the article here:

This week, we will begin our review of Samaadhi - the eighth and final limb of Yoga - starting with six key concepts. You can click on the links provided to dive deeper into each concept.

Then, next week, we will go over the various levels of Samaadhi, using the concepts outlined here.

A recap of some key concepts

In order to understand Samaadhi, it is important to have a grasp on six key concepts:

Pravritti and Nivritti: Evolution and Involution

Shabda, Artha, Jnana: Word, meaning, and idea

Lokapratyaksha and Parapratyaksha: Regular and higher perception

Vyutthaana and Nirodha Samskaaras: Outward and inward tendencies

Samapatti: Engrossment

Grahitr, Grahana, Graahya: The grasper, the grasping, and the grasped

Evolution and Involution: Pravritti and Nivritti

Consider a ball of Play-doh. The Play-doh can be moulded into the shape of a cup, a cylinder, a person, or anything else. These shapes are specific forms of the underlying, generic substance. Here, the Play-doh is known as saamaanya (literally “generic”) while the forms are known as vishesha (literally “specific”).

When saamaanya evolves into vishesha, it is known as pravritti, or evolution. When vishesha goes back into the saamaanya, it is known as nivritti, or involution.

In terms of Play-doh, when the cup, cylinder, person, or other forms are created from the Play-doh, this is pravritti. Then, when the forms are mushed back into a ball, this is nivritti.

Notice, any vishesha is nothing but the saamaanya with a different name and form. There is no additional factor there.

We know this because if we remove the saamaanya, the vishesha completely disappears. In the case of a cup made of Play-doh, if we remove the Play-doh, no part of the cup will remain. The cup is nothing but Play-doh, through and through.

A traditional example of this is waves and water. If we remove the water, no part of the wave remains. However, the wave can rise and fall, and the water will remain.

Said another way, there is a one-way dependence between the wave and the water, where the wave is dependent on the water, but not the other way around - the vishesha is entirely dependent on the saamaanya.

P: What does this have to do with Yoga?

When we see the wave, we are seeing the evolution - the pravritti - of water.

However, if we adjust our perspective, we can see the wave as nothing but water. This is nivritti. Yoga is just like this - a systematic process of nivritti by which we see everything as nothing but Prakriti.1

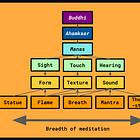

Look carefully at the image of the 25 Tattvas below.

The Tattvas are a cascading set of saamaanyas and visheshas. The buddhi is the vishesha of Prakriti, which is its saamaanya. In turn, the ahamkaar is the vishesha of the underlying buddhi, which is its saamaanya. This continues all the way down to the physical elements which we experience as water, fire, air, and so on.

Now consider your aalambanaa - this could be the breath, mantra, deity, or anything else that you are using as the support for your attention in meditation.

The aalambanaa is experienced as a combination of sensations - physical or subtle.

For example, if you use the breath as your aalambanaa, breath is air, which is experienced as a combination of texture and sound. Texture and sound are the tanmaatras - the saamaanya - for the breath. Next, texture and sound are experienced by the senses of touch and hearing. Without the senses of touch and hearing, you cannot experience the breath, and so we can establish the one way dependence - the senses are the saamaanya, and the tanmaatras (texture and sound, here), are the vishesha.

This continues all the way back up to the buddhi, and finally to Prakriti.

All objects - every single thing in this Universe - can be decomposed in this way, by involuting it back into Prakriti.

Said another way, the entire Universe is a sequential evolution - a pravritti - of Prakriti, and so can be seen as Prakriti through the process of involution - nivritti.

The purpose of Samaadhi is exactly this - a sequential nivritti of the aalambanaa, so that it can be seen as nothing but Prakriti, and ultimately non-self.

Word, Meaning, and Idea: Shabda, Artha, Jnana

Whenever we experience an object - whether it is subtle or gross - we are actually experiencing three things at once:

Shabda: Word

Artha: Object, or meaning

Jnana: Idea, or category

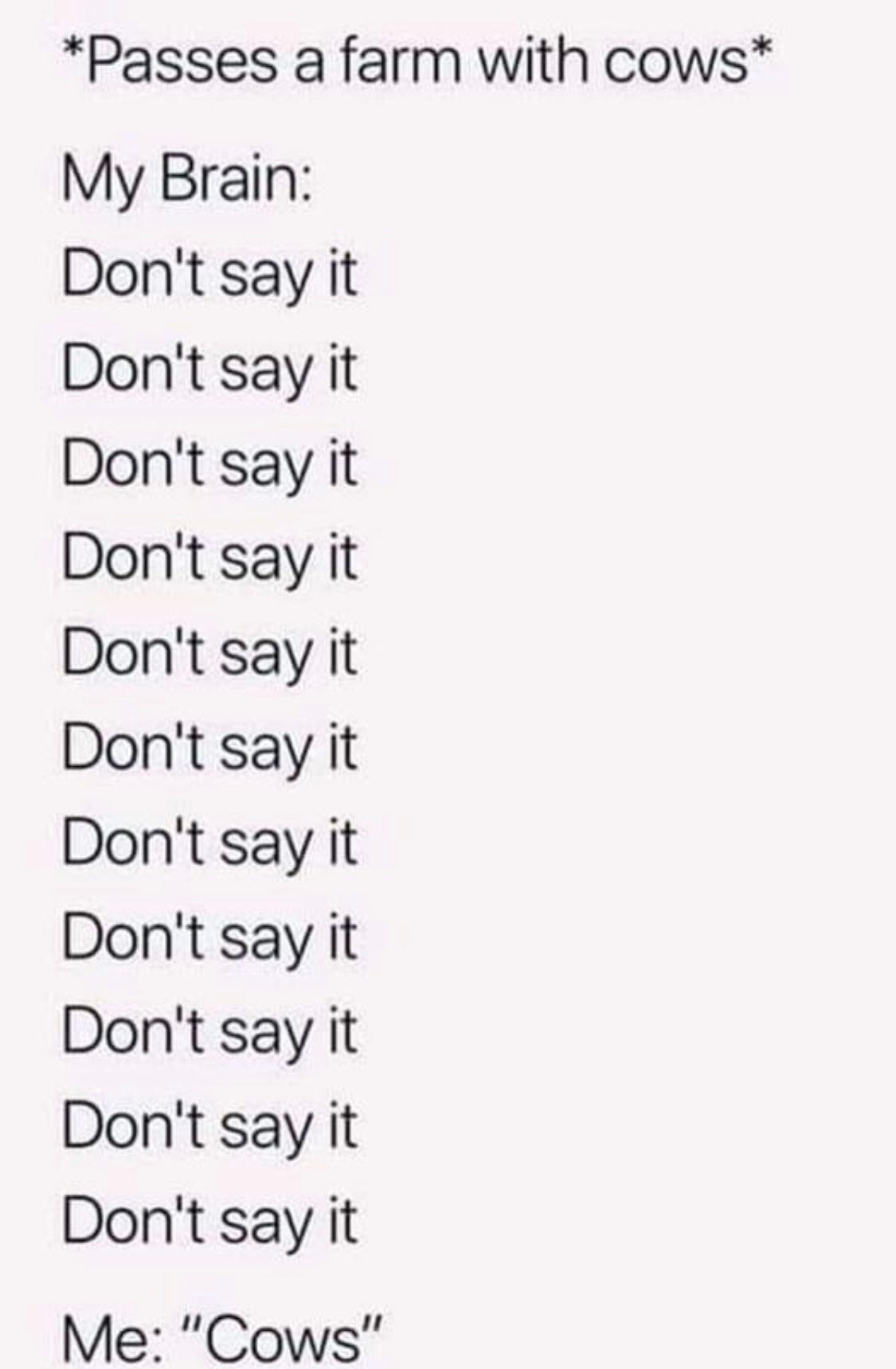

The traditional example is that of a cow.

When you see a cow, three things happen in quick succession. We see the physical cow - this is the artha. The word “cow” appears in the mind - this verbal signifier is shabda. Finally, the classification of the object into the class “cow” required the recall of the category “cow” - this category, or idea, is jnana.

Normally, these three appear in such quick succession that we cannot tell them apart. However, if we look closely, we will find that they are, in fact, three separate mental movements.

P: How is this relevant to Yoga?

We experience the world through a veil of thought.

Everything we experience is categorized neatly into boxes that we have inherited through language. As a result, when we see a cow, we split our attention between the actual cow, the word, and the category.

This is also true for people - we rarely see people for what they are. Rather, we categorize them into “good”, “bad”, “man”, “woman”, “Hindu”, “Muslim”, and so on, and then base our actions and thoughts on these categorizations.

In reality, all categories are just figments of thought - symbols that we use for convenience. However, we mistake these categories for the reality, and so end up living in a world of symbols, rather than in the Reality in front of us.

“The menu is not the meal.”

- Alan Watts

The two types of perception: Lokapratyaksha and Parapratyaksha

There are two types of perception - regular, or mundane perception (loka-pratyaksha), and the higher perception (para-pratyaksha).

When shabda and jnana are intermingled with artha, it is known as lokapratyaksha. When artha appears alone, without shabda and jnana, it is known as parapratyaksha.

The practice of Samaadhi habituates the mind to parapratyaksha, thus allowing the Yogi to see the world unobstructed - without the veil of thought.

All the teachings of the various Moksha-shaastras (soteriological texts) are sourced in Parapratyaksha. However, since they must be communicated through language, there is a sort of distortion that occurs. This is the reason that Yoga prioritizes direct experience. Listening and reasoning can only take you as far as the limits of language. Beyond this, there is only the higher perception - Parapratyaksha.

Outward and Inward tendencies: Vyutthaana and Nirodha Samskaaras

All thought patterns stem from samskaaras - mental tendencies, channels, or seeds.

These samskaaras are, in turn, generated from repeated thought patterns. For example, the more we think about food, the more we are likely to think about food. The more we allow or cultivate anger, the more likely it is for anger to appear automatically.

For any thought pattern, the more we allow it to sit in the mind, the more habitual it becomes, creating cycles that are hard to break.

These patterns - samskaaras - can be classified into two categories - outward (vyutthaana) and inward (nirodha). These are not absolute, but rather relative categories. That is, the same samskaara may be outward when compared with something, but inward when compared with something else.

Vyutthaana (outward) samskaaras are counterproductive to Yoga, while Nirodha (inward) samskaaras help to expedite progress. In fact, all the techniques in Yoga can be seen as a systematic method of reducing the proportion of vyutthaana samskaaras and increasing the proportion of nirodha samskaaras in the mind of the practitioner.

Samapatti: Engrossment

Samapatti is defined as any moment in which the distinction between the knower, the known, and the process of knowing completely disappears.

Samapatti can occur even without samaadhi.

For example, you have likely experienced samapatti when seeing an expansive and beautiful view for the first time, or when you are deeply engrossed in reading a book, or watching a movie. Any time “you” disappear, and you are entirely absorbed in the object of experience, it is samapatti.

P: What does samapatti have to do with Samaadhi?

Samapatti is a prerequisite for Samaadhi. In fact, the levels of Samaadhi are just different types of samapatti.

Grahitr, Grahana, Graahya: The grasper, the grasping, and the grasped

In any perception, there are three essential components - the knower, the known, and the instruments of knowledge that connect the two. These are known as grahitr (literally “the grasper”), graahya (literally the “grasped”), and grahana (literally “the instruments of grasping”).

As an example, as you are reading this right now, your mind is the knower (the grahitr), your eyes are the instruments of knowledge (the grahana), and the words on the screen are the known (the graahya).

Normally, we identify with the grahitr, or knower. We say things like “I read the article”, or “I saw the cat on the porch.” However, if we notice closely, we see that the Self is the observer of all three aspects of knowledge. The Self is the witness of not only the known and the instruments of knowledge, but also of the knower itself.

In Samaadhi, we begin by bringing attention to the graahya - the object - since this is what we are most used to. As Samaadhi deepens, attention turns to the grahana - the instruments of knowledge, such as the senses, the mind, and so on. Finally, attention turns to the grahitr - the knower within the mind - making it clear that even the knower is an object to You, the Self.

This is the stepwise process of Samaadhi.

TL;DR

In this article, we continued our singha-avalokana-nyaya - revisiting the six key concepts that are necessary to understand Samaadhi - the eighth and final limb of Yoga. The concepts are:

Pravritti and Nivritti: Evolution and Involution

Shabda, Artha, Jnana: Word, meaning, and idea

Lokapratyaksha and Parapratyaksha: Regular and higher perception

Vyutthaana and Nirodha Samskaaras: Outward and inward tendencies

Samapatti: Engrossment

Grahitr, Grahana, Graahya: The grasper, the grasping, and the grasped

Thus far in our singha-avalokana-nyaya, we have reviewed

We then discussed a few frameworks which are helpful throughout the journey:

The twin foundation of Yoga: Practice and Letting Go

Next, we began a discussion on the techniques, starting with the foundational methods:

Eka-tattva-abhyaas: Focusing on one thing at a time

Six stabilizing techniques: Spot-fixes to calm the mind

The Brahmavihaaras: Four attitudes to calm the mind regardless of external circumstance

Kriya Yoga: The method to weaken the kleshas, and build willpower and discipline

Then, last time, we began our discussion on the eight limbs, specifically focusing on the five external limbs of Yoga. Each of these limbs had several articles, so the first of each has been linked below:

Yama: External observances

Niyama: Personal conduct

Aasana: Posture

Praanaayaam: Lengthening the Praana

Pratyaahaar: Sense withdrawal

Last time, we reviewed Dhaaranaa and Dhyaan - the first two of the internal limbs, following it up with this week’s article reviewing the key concepts necessary to understand Samaadhi.

Each layer of Samaadhi has its unique characteristics by which we can identify them. They have names, and are sequential in nature.

Next time, we will review the levels of Samaadhi, using the concepts that we revisited here.

Next time: The Prescription: Part VII

In Advaita Vedanta, this nivritti is taken a step further, and everything is seen to be nothing but Self.