The Four Attitudes

Friendliness, Compassion, Gladness, and Equanimity

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Our relationships with other people can be a source of tremendous happiness and fulfilment, but also of tremendous suffering. Think about the last time you felt jealous of someone else’s success. Now think, was this a pleasant feeling? What about a time when you felt annoyed or angry at someone else’s actions?

On the other hand, consider a time that you felt a genuine sense of happiness at another person’s happiness - remember the pleasant feeling in the mind. This feeling of mental calm, clarity, pleasantness, and lucidity is called chitta-prasaadanam, and this week we will discuss how to bring it about regardless of the situations we may find ourselves in.

The method is called bhaavanaa, or cultivation of a particular feeling. While at first it can take some effort, eventually, as the channel in the mind gets deeper, with continued practice and dispassion, these attitudes become second-nature.

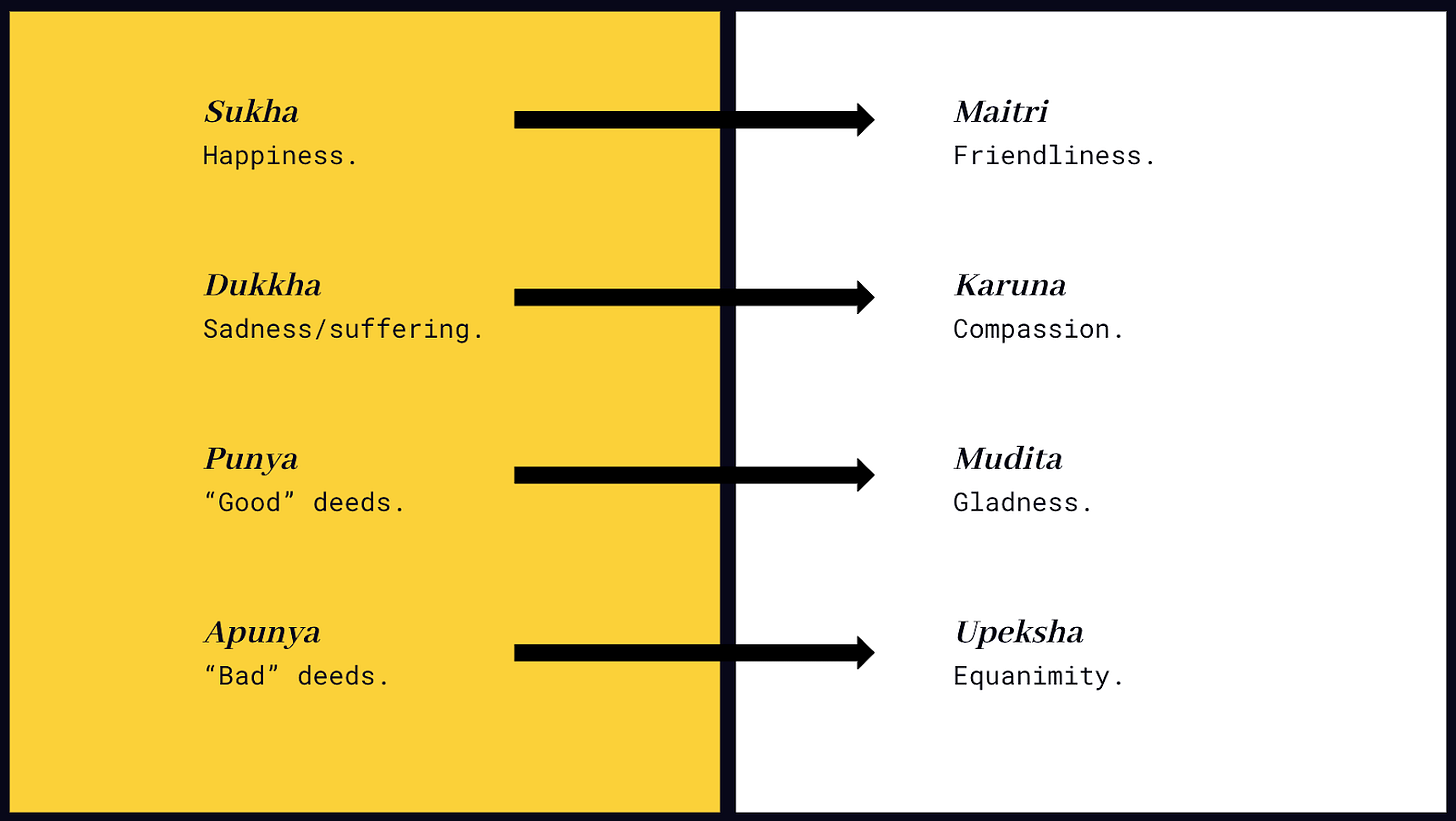

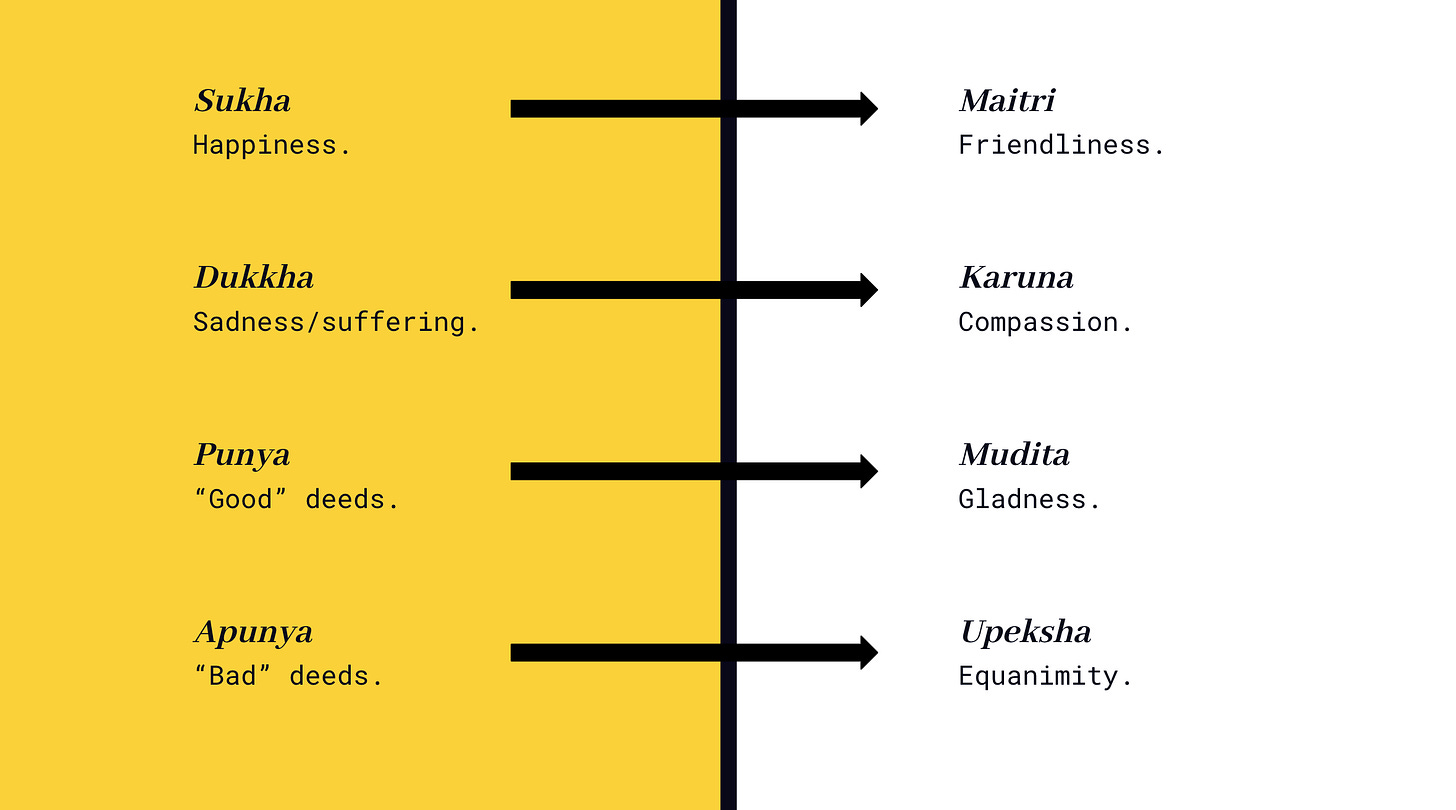

मैत्रीकरुणामुदितोपेक्षाणाम् सुखदुःखपुण्यापुण्याणाम् भावनातश्र्चित्त्तप्रसादनम् ॥MaitriKarunaMuditaUpekshaanaam SukhaDukkhaPunyaApunyaanaam BhaavanaatashChittaPrasaadanamCalm (ie. chitta-prasaadanam) arises in the mind by cultivating an attitude of friendliness towards those who are happy, compassion to those in suffering, joy towards those who are virtuous, and equanimity to those who are not virtuous.

- Yoga Sutras 1.33

All situations in our relationships with other people fall into one or more of the following four categories:

Sukha: When you see that someone is happy

Dukkha: When you see that someone is sad

Punya: When you see someone else’s success, or see someone commit a “good” deed

Apunya: When you see someone else’s failure, or see someone commit a “not good” deed

When we experience any of the the four situations above, feelings may arise in the mind - sometimes the feelings lead to mental calm, but other times these feelings can create inner turmoil. The skill we will go over today is the cultivation of particular feelings in particular situations, such that the mind can remain calm regardless of the situation. These feelings are known as the Brahmavihaaras, or the “Divine Abodes”, and are extensively discussed not only in Yoga, but also in Buddhist literature.

In each of these situations, if we cultivate any feeling other than the Brahmavihaara, it will lead to feelings of inner suffering and mental disturbance. However, if we are able to skillfully cultivate the appropriate Brahmavihaara, it leads to chitta-prasaadanam, or mental peace, stability, clarity, and pleasantness:

When you see that someone is happy, cultivate friendliness

When you see someone suffering, cultivate compassion

When you see someone else’s success, or doing a “good” deed, cultivate gladness

When you see someone else’s failure, or doing a “not good” deed, cultivate equanimity.

Near and Far Enemies

For each of the Brahmavihaaras, there is a near enemy and a far enemy. These are indications of whether you are succeeding or failing at cultivating the attitude. The far enemy is the opposite - the furthest away you can get from the attitude you are trying to cultivate. If you are successful at cultivating the attitude, you will notice tendencies towards the far enemy subside.

The near enemy is the dangerous one - like an enemy masquerading as a friend. On the surface, it may appear much like the Brahmavihaara, but upon closer inspection it is contrary to it. If the near enemy is still present, this is an indication that you have not yet succeeded in cultivating the attitude, but noticing the near enemy is a sign of progress.

This may seem quite theoretical at this point, but will become much clearer as we go through the examples.

Maitri: When you see happiness, cultivate friendliness

When we see that someone else is happy, we can feel a resistance to it. This resistance may manifest as jealousy or sadness, where you wish that happiness for yourself. It may manifest as distancing - you don’t want to be around them because they are happy and you are not. It can also manifest as annoyance at their happiness, or even, in some cases, anger.

Instead, cultivate maitri, or friendliness, to calm and clear the mind. This is a feeling of love and kindness towards the other person, and can be generated by looking closely to see the lovableness in them. It can also manifest as a feeling of benevolence, wishing the other person well, and feeling an active interest in their well-being. By doing this, you will notice that the feeling of annoyance dissipates, and your mind feels calmer and clearer.

The far enemy of maitri is hate or ill-will. This is the furthest you can get from the feeling of friendliness. One cannot feel both friendliness and ill-will simultaneously, and so cultivation of maitri results in, and is strengthened by, the letting go of ill-will.

The near enemy of maitri is greed, attachment, or selfish affection. This means that on the surface we may appear to be a well-wisher, or even feel a sense of benevolence towards the other person - but out of attachment, fear, and selfishness rather than open-heartedness. For example, one might feel “I will love you if you love me back” or “I wish you well because it benefits me.” Instead, maitri is a cultivation of friendliness such that you wish for the other person’s happiness, regardless of your own gain.

The Brahmavihaaras are presented in order of difficulty. Maitri, being the first, is the simplest to cultivate.

Phrase: “May you be happy” or “May you be well”

Karuna: When you see suffering, cultivate compassion

When we see that someone else is suffering, we may feel upset and sad. Depending on our tendencies, we may also feel a sense of imposition, frustration, or even anger. If we are honest with ourselves, there may even be some people for whom we feel happiness at their suffering. In the face of suffering, any of these feelings will lead to a mind that is disturbed and cloudy.

Alternatively, the Yogi should cultivate karuna, or compassion. This is a feeling of love and warmth towards others that prevents the desire to abandon those who are suffering.

Compassion is not the same as empathy or sympathy.

With sympathy, there is a mental understanding of the other person’s suffering. Empathy takes that a step further with viscerally feeling what the other person is feeling. However, empathy can be extremely draining - this is called “empathic distress.”

Empathic distress is defined by psychologists Tania Singer and Olga Klimencki as: “a strong aversive and self-oriented response to the suffering of others, accompanied by the desire to withdraw from a situation in order to protect oneself from the excessive negative feelings.”

When we feel empathic distress, there is a tendency to avoid situations where we come face to face with the suffering of others. In addition, research shows that empathy can increase in-group bias, and increase feelings of distance from those we consider to be different from ourselves. In sum, while empathy is better than sympathy or apathy, it is still a me-focused feeling, and is limited. That is, after a while, the fountain of empathy dries up, and we feel like we must withdraw in order to take care of ourselves.

This is where compassion comes in. With compassion, not only do you recognise the suffering of the other person (ie. sympathy) and feel it directly (ie. empathy), but you add one more ingredient - a willingness or readiness to alleviate the suffering. Thupten Jinpa, the principal author of the course Compassion Cultivation Training (and the principal English translator to the Dalai Lama) defines compassion as a four step process:

Cognitive: An awareness of suffering

Affective: A sympathetic concern related to being emotionally moved by suffering

Intentional: A wish to see the relief of that suffering

Motivational: A responsiveness or readiness to help relieve that suffering

Unlike empathy, compassion is an infinite resource. By skilfully cultivating compassion rather than simply empathy, the likelihood of burnout is significantly decreased.

Empathy works by seeing a suffering person as a part of your “in-group.” This essentially means that you are drawing a boundary where some people fall into it, and others fall outside of it (ie. people like us vs. people like them). At worst, it can lead to feelings of aversion to those we consider different from us. Compassion, on the other hand, works by extending or dissolving the boundaries of your in-group to include more people. As a matter of fact, all the four Brahmavihaaras work this way.

The proximate cause of compassion is the awareness of helplessness in a person overwhelmed by suffering.

Let us take an example to make this clear. Let us say you are walking down the street and you see someone begging on the side of the road. Depending on your mental tendencies, you might think “why can’t they go and find a job” or “if they just stopped taking drugs they could solve their own problems.” Now let us investigate - what happened here?

The first step was a separation of self and other. That is, you identified the person as different from you. They are unhoused, you are not. They are on drugs, you are not. They are unwilling to work, you are not.

Also, there was mental activity in your mind that was not pramaana (evidence), but rather viparyaya (error) or vikalpa (imagination). You do not know of their housing situation, their drug use, or their employment based on a quick look at them, yet you imagine these to be true. Perhaps they are, but it is not based on evidence.

Then, based on these viparyaya and vikalpa vrittis, additional feelings arose - perhaps anger or frustration, based on the imagination that they are not helping themselves. These feelings are unpleasant, and lead to a clouding or disturbance of the mind.

Now instead, let us take a look at what you know only based on evidence (pramaana). The person is standing on the roadside, asking for help. Perhaps they are not clean, maybe they look tired or frustrated. Clearly, they are suffering. This is all you know - anything else is imagination or error.

At this point, touch the suffering directly - without any judgement, preconceived notions, or other interfering ideas. Due to innumerable causes and conditions, this person is suffering. Notice the aspect of helplessness - they want to stop suffering, just like you, but are unable to do so. If they were able, they would have done so. No one wants to suffer.

Here, cultivate a desire that their suffering be alleviated. Once this is solidified, cultivate a desire to help in some way, even if this means just mentally wishing that their suffering be alleviated. Whether or not you actually go out and help is a different matter, but actively cultivate a motivation to alleviate their suffering. This is karuna, or compassion.

The far enemy of compassion is cruelty. This is the furthest you can get from compassion, and is characterised by an active desire to harm others. Cruelty and compassion cannot arise in the mind simultaneously, and so cultivating compassion automatically weakens any tendencies towards cruelty.

The near enemy of compassion is pity. It closely resembles compassion but is opposed to it in a more subtle way. In both, one may want to alleviate suffering. However, in the case of pity, it is a self-focused motivation - you want to alleviate their suffering in such a way that it benefits you. Perhaps it makes you look good or feel superior, or perhaps you gain from it in some other way. The presence of pity indicates that the tendency towards compassion has not yet solidified.

Phrase: “Just like me, you too suffer. May you be free from suffering.”

A brief aside into Punya (karmic merit)

In order to understand the next two Brahmavihaaras, a brief aside into what the word “punya” means.

Punya (pronounced pun-yuh, where the first “u” is pronounced as in “put”) means “merit.” Specifically, this refers to a karmic merit that one receives as a direct or indirect result of good action. That is, generally speaking, if someone experiences happiness, good experiences, a good birth, a long life, it is the result of their punya. We will discuss the specifics of karma in a future article, but for the purposes of the next two attitudes, punya can refer either to a good deed that someone does in order to accrue punya, or to a positive result of punya.

To make this clear, let us take a few surface level examples - if someone gives food to a hungry person, this is punya. If someone wins the lottery, this is also punya. Now, as you might notice, it gets more subtle than this - giving food to a hungry person may not be punya if the motivation is selfish. With the lottery example, winning the lottery may not be punya if it is the cause of future suffering.

Additionally, the classification of an action or result as “good” is in itself problematic. One person may think that feeding a hungry person is good, while another may feel like it is furthering the problem of poverty and so classify it as “bad.” One person may feel like winning the lottery is “good” while another may see it as a potential cause of suffering and so classify it as “bad.”

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

- William Shakespeare, Hamlet

In the context of the Brahmavihaaras, whether an action or result is classified as punya (or its opposite, apunya), depends entirely on the mind that classifies it. The reason for this is that the classification itself is the cause of any associated feelings that arise. This will become more clear as we go into the next two attitudes.

Mudita: When you see punya, cultivate gladness

When we see someone doing a good deed, or if we see another person’s success (ie. punya), we may feel jealous, inadequate or sad. Depending on our tendencies, we may also feel frustration or anger towards the other person. These feelings are painful, and cause the mind to be disturbed and cloudy.

Rather, in order for the mind to remain peaceful, we should cultivate mudita - gladness or empathetic joy. The exponent of gladness, according to the Buddhist philosopher Buddhaghosha, is one who “laughs first and speaks afterwards.” You might recognise this feeling in yourself when you see a close friend after a long time, or when you see a child’s success. It is not to be confused with pride, in that with mudita, there is gladness regardless of any benefit to you.

The key to mental clarity in the face of punya is to cultivate this feeling with all people - whether they are friendly or neutral to you, and no matter how much pain they may have caused you. In fact, the test of mudita is to feel gladness for others’ happiness, even when you are facing hardship yourself.

P: What if someone is feeling happiness at someone else’s suffering? Should I be glad for their happiness?

Jogi: Do you mean sadistic pleasure?

P: Yes.

Jogi: In this case, cultivate compassion for the person who is suffering.

As with all the Brahmavihaaras, at first it may be an effort to cultivate the attitude. But over time, with repeated practice and letting go of counteracting tendencies, it will become second nature.

The far enemy of gladness is jealousy. This is the furthest you can get from gladness, and is characterised by an explicit desire to have what the other person has.

The near enemy of gladness is shallow-merriment, or grasping out of insufficiency. This looks like you are glad, in that you may look happy externally, or even feel happy internally. The difference lies in the self-focused motivation of shallow-merriment, and the other-focused motivation of gladness.

To make this clear, let us take an example of someone who has just bought a large, beautiful house. You may be their friend, and they invite you over to their housewarming party. If you are happy for them insofar as it benefits you (ie. you are happy because you get to hang out there, or because you will be able to throw parties there), this is what is meant by shallow-merriment. It will look to others as though you are genuinely happy for them, and it may even seem this way to you. As with the other Brahmavihaaras, the near enemy masquerades as the attitude, although it is truly opposed to it in a subtle way.

Phrase: “I am glad you act this way” or “I am glad this happened to you.”

Upeksha: When you see apunya, cultivate equanimity

Apunya (pronounced uh-pun-yuh) is the opposite of punya. It includes anything that is not classified as “good” action. This could mean “bad” action (e.g. if you watched someone hurt someone else - physically or verbally), or “neutral” action (e.g. watching someone tie their shoelaces or walking on the street).

As with punya, apunya depends on the mind of the observer - your judgement of the situation is what results in any feelings that arise with regard to it.

Apunya also includes results. For example, if you see that someone has failed in what they were trying to do, this is apunya. A subtle point - the suffering that ensues from their failure is dukkha, and should be met with compassion. Apunya refers to the situation itself. For example, if someone did not get a job that they wanted - the fact of them not getting the job is apunya, but their sadness or frustration from not getting it is dukkha (suffering).

Normally, when we see someone doing a bad deed, or witness an apunya of any sort, we can feel angry or outraged, upset, or sad. Depending on tendencies, one may even feel happy!

Instead, in order to calm the mind, the Yogi should cultivate upeksha, or equanimity. This is the last of the four attitudes, and by far the most difficult to cultivate. The ability to cultivate equanimity comes after the first three attitudes have been strengthened. Furthermore, establishing equanimity solidifies the first three attitudes. The traditional example used is that of a roof with rafters - just as the rafters cannot be placed in the air without first having set up the scaffolding and framework of beams, so equanimity cannot be developed without already having developed friendliness, compassion, and gladness.

To help illustrate what equanimity means, here is a short story from the Buddhist tradition:

Once upon a time, there was a novice monk who wanted to practice his daily meditation, but was unable to find a quiet place within the monastery. As he searched for a nice spot, he eventually wandered around outside the monastery gates, and came across a boat on the nearby river. It was empty, and the surroundings were nice and quiet, so he climbed in, sat down, and closed his eyes to meditate.

Hours went by, and his meditation was extremely peaceful. Suddenly, he felt a hard bump. Someone had bumped into his boat!

Keeping his eyes closed, so as not to disturb his meditation, he felt immense anger bubbling up inside of him. He felt feelings of blame - “how could this other boatman be so careless as to bump into my boat!” and frustration - “why didn’t the boatman just look at where he was going!”

Eventually the anger was too much for him to handle, and so he opened his eyes to yell at the boatman. The sun had set, and the fog was starting to set in, but as he looked closely through the haze, he saw that the other boat was completely empty!

Immediately his anger disappeared - there was no one to blame.

Just like the monk in the story, we look around us and see people as responsible agents, and as a result, blame them for their bad deeds (or what we deem as bad anyway). Instead, if we see people as empty boats - simply combinations of several causes and conditions - the anger we feel simply disappears. This is equanimity.

In reference to this story, the ancient Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou says:

If a man is crossing the river and an empty boat collides with his skiff, even though he is a bad-tempered man he will not become very angry. But if he sees a man in the other boat he will scream and shout and curse at the man to steer clear. If you can empty your own boat crossing the river of the world, no one will oppose you, no one will seek to harm you. Thus is the perfect man – his boat is empty.

That is, the idea of equanimity need not only be applied to others, but can also be applied to oneself. Normally, we view ourselves as a separate agent in this world, but rather, viewing ourselves as an empty boat we can live in harmony with the flow of the Universe rather than raging against it.

P: So if we see someone doing a bad deed, we should just accept it and move on? Are you saying we shouldn’t fight against injustice?

Jogi: Not at all. Fight injustice where you see it, but do it with a clear mind. While anger can be a motivating agent, it clouds judgement and weakens the intellect. Additionally, it results in a life spent suffering. Rather, with equanimity, one can clearly see the causes and conditions that lead to an action or a result, and thus counteract the “bad deed” much more effectively - with a calm and clear mind.

Thich Nhat Hanh, the famous Vietnamese Buddhist monk and human rights activist says:

“If you nourish your hatred and your anger, you burn yourself. Understanding is the only way out. If you understand, you will suffer less, and you will know how to get to the root of injustice.”

Rather than making ourselves more upset and angry at a given situation, we can apply equanimity to accept that the situation has occurred, and investigate without judgement to find the causes and conditions that led to it. With a calm mind, we can then understand the situation more deeply, and thus counteract it more effectively than if we were simply outraged.

The far enemy of upeksha, or equanimity, is resentment and approval - blame and praise. These are the furthest one can get from this Brahmavihaara. We will discuss these in more detail next time.

The near enemy of upeksha is indifference, or apathy (also known as the equanimity of unknowing). On the surface, both indifference and equanimity share the common quality of seeing past virtues and faults, but differ in a more subtle way. While indifference and apathy require a closing off of the outside world, like an ostrich with its head in the sand, or a horse with blinders on, equanimity is the complete opposite - directly looking at the situation and investigating the causes and conditions closely, and without fear or judgement.

Phrase: “I understand the cause of your choices”

How do I use this teaching in my life?

The practice of the Brahmavihaaras is not only a seated practice - it is to be applied every day, throughout life. Every interaction with another person is an opportunity to practice this method. The attitudes are to be cultivated in the order presented - Friendliness (Maitri), Compassion (Karuna), Gladness (Mudita), and Equanimity (Upeksha) - and are in ascending order of difficulty. The idea behind this is as follows:

Maitri (Friendliness/Loving Kindness): First you promote the welfare of all beings.

Karuna (Compassion): Then, seeing that those beings whose welfare you promoted suffer, promote the removal of their suffering.

Mudita (Gladness/Empathetic Joy): Next, seeing the success of those beings upon the removal of their suffering, be glad.

Upeksha (Equanimity): Finally, since there is nothing more to be done, be equanimous.

Now arises the question of whom to apply these teachings to. In increasing order of difficulty:

Oneself: Towards yourself.

The dear one: Towards someone you love.

The neutral one: Towards someone you don’t feel either way about - perhaps someone you see while walking on the street, or someone who serves you coffee at a coffee shop.

The difficult/hostile one: Towards someone who is hostile towards you, or (if you don’t have someone like this) someone who you feel it is difficult to be around.

Sometimes, especially in the West, this is taught starting with the dear one, and ending with oneself. Play around with it to see what you find easiest, and start there. Move on to the next when you feel comfortable doing so.

Finally, once you feel comfortable applying these attitudes to one person at a time, they can be extended. The classical example here is that of a farmer who delimits one part of their land to plough the soil, rather than trying to plough the whole farm at once. Start with one person, then your own household, and then extend from there. To quote Buddhaghosha from his text the Vishuddhimagga,

“When the mind has become malleable and wieldy [with respect to a single dwelling], expand to two dwellings, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, one street, half the village, the whole village, the district, the kingdom, one direction, and so on up to one world-sphere, or even beyond that.”

Until next time:

As you go about your day, categorise situations in your life using this framework: sukha, dukha, punya, apunya.

Notice your default mental reaction to each situation.

Try to cultivate the appropriate Brahmavihaara, and notice how it makes you feel.

As always, take notes to better understand your own tendencies, and don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions, comments, objections, or feedback!

Next time: Boundaries