Your senses create the world

Primal Ignorance and the 25 Tattvas: Part I

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

If I told you that I was a tomato, you would think I misspoke. If I insisted that I was a tomato, you would think perhaps I was joking. If I continued to assert that I was a tomato, you would think there was something wrong with me.

Now, if I truly believed I was the tomato, when it is threatened, I will feel fear and anxiety. When it begins to rot, I will feel sadness and worry.

This is our current situation, and it is called avidya (pronounced uh-vid-yah), or the Primal Ignorance.

According to the philosophies of Yoga and Vedanta, we have confused ourselves with objects of experience, and this confusion is the root of all our suffering. (Incidentally, it is also the root of desire, and so of karma, but more on that later). The purpose of all the four Yogas, discussed last week, is to ultimately remove avidya, and so to allow for your ever-present freedom to shine through. This is moksha - freedom from all suffering.

We usually have no trouble differentiating ourselves from objects outside the boundary of our skin. For many of us, it is also fairly easy to see the body as an object. However, when it comes to the mind, it is a totally different situation. We identify with our mind completely - we think we are the mind - and this can result in immense suffering.

The purpose of the next few articles in this series will be to shine a light on the mind so that we can see how it functions, and in doing so start to see it as an object in our experience, rather than as the essence of our being. In this way, having a framework to understand the mind helps us to make sense of what can otherwise feel like a tangled mess.

Consider two scenarios.

In one, you are driving to your destination without using Google Maps. You are on your way, expecting to get there in 30 minutes or so, but about halfway through your drive, you hit unexpected traffic. You panic - you are going to be late, and you start to consider alternative routes. Not knowing the roads well enough, perhaps, in your panic, you take a wrong turn. Now things get really bad - you start to ruminate about all the things you could have done differently so you would have been on time. Perhaps you could have left 10 minutes earlier, maybe you shouldn’t have run back to the house to change your jacket, maybe it’s not your fault after all, and your husband, wife, kids, roommate is to blame for the current predicament. How terrible they are for having done this to you. Now you wonder what you’re going to say when you get to the destination. Will you have to apologise? Will the whole evening be a disaster? The mind has become scattered, tired, and cloudy, but the traffic has not changed.

In another scenario, you’re driving, but you’re using Google Maps. You are on your way, but this time you expected the traffic, and you knew the best route. The app told you approximately when you would arrive, and you were able to deal with the situation. No one is to blame, and your mind remains calm as you enjoy the music in your car.

The only difference between these two situations is the fact that you had knowledge of the traffic beforehand. You were able to set the expectation in your own mind that matched the reality, and this allowed you to navigate (pun very much intended) the situation without freaking out about it. This is why Yoga begins with learning about the mind.

If we don’t understand the mind, it appears as a tangled mess of perceptions, thoughts, memories, and emotions, that flares up unexpectedly leading us to actions that we later regret, or feelings that we cannot seem to overcome.

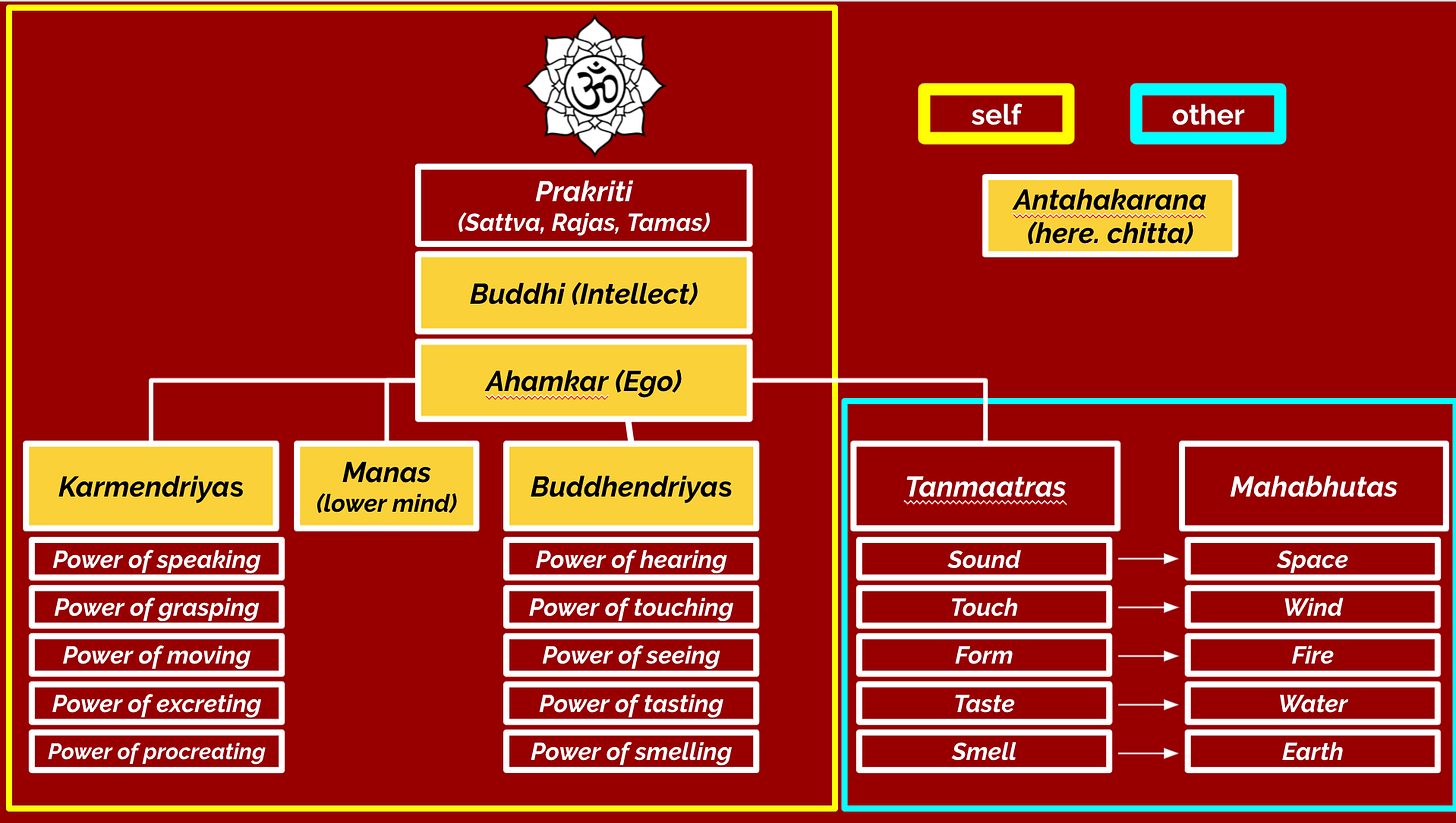

Today, we will start to go over the basics of Yoga Psychology. The framework we will use is called the 25 Tattvas, and is intended as a flashlight to help you notice, understand, and eventually explore the depths of your own mind. The word “Tattva” simply means “that-ness”, and this framework breaks down the entire Universe into 25 categories, or 25 things (because a “thing” is nothing more than a category). As you will notice, there is a lot of enumeration (5 of this, 4 of that, 3 of this other thing). The philosophy from which this is borrowed is called Sankhya (pronounced Saan-khyuh), which literally means “enumeration” or “numbering.”

In this article, we will go over the following categories from the diagram above:

Mahabhutas: Physical/Gross elements

Tanmaatras: Subtle elements

Buddhendriyas: Organs of perception

Karmendriyas: Organs of action

Next week, we will discuss:

Manas: Lower mind

Ahamkaar: The “I”-maker

Buddhi: Intellect

And finally, we will go over Prakriti, and then Purusha.

There is a lot of detail to cover, but this is critical as a basis for Raja Yoga, and is also extremely helpful for Vedanta. Additionally, having a framework to understand the mind and the Universe provides us with a common language with which we can frame our experiences, and allows us to deal with situations in our day to day lives in a skillful manner.

Like in the driving example above, consider this framework to be a map of your inner workings, and your relationship with the world around you.

Let us start by focusing on the coloured outlines in the diagram above. The yellow outline is what we normally consider to be “self.” This includes things like body, mind, senses, and Awareness. The blue outline is what we normally consider to be “other” - this includes the physical world, and sometimes includes our bodies too (e.g. in the sentence “I hurt my foot” - the body is an object, but in the sentence “I am tall”, the body is identified as “self”). We will go over each category in some detail:

The 5 Mahabhutas: Gross/Physical Elements

This category is the external physical world that we see all around us. The Sankhya philosophy (as well as many other ancient philosophies from around the world) states that the entire gross/physical Universe is composed of only these 5 elements. They are:

Aakaasha: Space

Vayu:Wind

Agni: Fire

Aapa: Water

Prithvi: Earth

We needn’t take this cosmology too seriously, because in our day and age we have a highly sophisticated science for breaking down the physical Universe. However, it is useful in that the methods prescribed in Yoga, Vedanta, and related philosophies use this cosmology to return to Purusha, or the Self.

Additionally, any framework is just a way of slicing the world. Take the example of your hand. If you were using your hand to teach a child to count, you would not use the framework of arteries, veins, bones, joints, tissue, etc. that you might use if you were teaching surgery to a class of medical students. You would simply differentiate between fingers, and use the framework of “open vs. closed” to signify the numbers from one to five. Conversely, you would not use this simple framework to teach surgery, but - and this is important - that doesn’t make it any less correct. They are both simply different ways to slice the world.

Similarly, with the physical world, if you are interested in using your understanding of nature to build a bridge, the framework of Newtonian physics would be tremendously helpful. If you want to use your understanding of nature to create medicine, the framework of chemistry is your best bet. However, if you’re trying to understand quantum mechanics, you need to throw both of those out the window, and use the framework of subatomic particles, waves, and probability functions. None of them are more or less correct - they are simply different ways to slice the world.

With Yoga, knowing Mendeleev’s periodic table is good, but not particularly helpful. The Yogi is less concerned with physical nature than with the nature of Self, and so this simplistic model will do just fine. But again, like with any framework, don’t take it too seriously - a framework is only a symbol to represent reality, not reality itself.

To quote Alan Watts, “the menu is not the meal.”

The 5 Tanmaatras: Subtle Elements

This category is apparent in our everyday experience, but we often take it for granted or mix it up with other objects of experience. They are the 5 Tanmaatras or “essential essences.” They are:

Shabda: Sound

Sparsha: Texture

Roopa: Form

Rasa: Taste

Gandha: Smell

Notice, these are related to the five sense organs (below, the organs of knowledge), but are different from them. One uses the power of hearing to hear sound. One uses the power of smell (ghraana) to smell smells (gandha) (yes, English is confusing - Sanskrit is very precise).

Sound can also be considered as the “pure element of space”, while the gross/physical element of space is seen as a mixture of a quarter of the sound tanmaatra, and an eighth of each of the others. It is the same with all the other tanmaatras, as shown in the diagram below. This combination is what is said to make the gross elements.

The implication of this is huge. Normally, we think that an object exists outside, and its characteristics lead us to hear, touch, see, taste, or smell it. In Yoga, the object evolves from form, taste, smell, etc. If you think about it, it is an accurate representation of our experience.

We don’t actually see an object - we see form, and then presume an object to exist “out there”.

Our entire world, including the physical body, is made of these tanmaatras. Another way to say this is that there are only 5 objects in the physical Universe, and we mentally combine them to make the manifold that we see and take so seriously.

The 5 Buddhendriyas: Organs of Knowledge

This category is the 5 sense organs. The word “buddhendriya” comes from a combination of the word buddh which means “to know” or “to perceive”, and the word indriya which means “sense organ.” It is through these five doorways to the mind that we gain any and all knowledge:

Shrotra: Power of hearing

Tvak: Power of touching/feeling

Chakshus: Power of seeing

Rasana: Power of tasting

Ghraana: Power of smelling

The first thing to note is that these are different from the physical organs. In Sanskrit the words are also different (e.g. the power of hearing is shrotra, but ears are karna; the power of tasting is rasana, but the tongue is jihva). These represent the subtle ability to hear, feel, etc., not their physical counterparts.

In our experience, we can use the power of hearing without a physical sound. To illustrate this, consider a time when you had a song stuck in your head. You weren’t mentally singing it, it was just there, and you were using your subtle power of hearing to listen to it.

It is this same subtle power of hearing (shrotra) that we use when “listening” to a mantra during meditation, or “listening” to our inner monologue. The inner monologue, mantra, or any subvocal thought is a shabda tanmaatra (subtle element of sound) being listened to by the shrotra buddhendriya (subtle power of hearing).

For many, this can be a huge revelation - your inner monologue is not you, it is just another sound playing in your head.

The tanmaatras and the buddhendriyas are related too, by way of the ahamkaar (which we will discuss in detail next week). Sound emerges from the power of hearing, form emerges from the power of sight. Normally, we think of it exactly in the opposite way - we feel like there is an object, the object has a form, and our power of sight sees the form. Rather, it is quite the opposite - without sight there would be no form, and without form there would be no object. Object emerges from form, which further emerges from sight (sight -> form -> object).

Consider the sun - it has light and heat. Imagine a Universe now, in which there were no eyes. With no eyes, there would be no light either. Light is only light when there are eyes to perceive it. Similarly, a hard surface is only hard in relation to the softness of skin. A sound is only a sound when there is an ear to hear it.

Our senses do not just perceive the manifold Universe, they create it.

This is not some abstruse philosophy, it is right here - the truth of our everyday experience.

P: Does this mean that the Universe wouldn’t exist if there were no one to perceive it?Jogi: If a tree falls in a forest, does it make a sound?P: Does it?Jogi: What is the sound of a one-handed clap?P: Huh?

Jogi: Let us consider the example of the tree falling in a forest. It falls, and it creates a vibration in the air. The vibration is nothing but a pulsation of air. The pulsing air turns into “sound” only when it hits the ear of the perceiver. In this sense, there is no sound without a perceiver. Sound and ear go together like two sides of a coin - there cannot be only one side to a coin. P: But is the vibration there?Jogi: It is like asking the question “if there were only one side to a coin, would the coin exist”? There cannot be a one-sided coin, and so the question itself includes an impossibility. We can go out on a limb, with faith, and say that there is a vibration, and then try to figure out what its nature might be. However, we would then be spinning in circles trying to find a fictional solution to a fictional problem. There are no one-sided coins, so there can be no question of its existence or non-existence. In this way we can dissolve the question rather than solve it, for there is no question to begin with.There is also a relationship between the senses of perception and the 5 physical elements! Space can only be heard, Wind can be heard and felt, Fire can be heard, felt, and seen, Water can be heard, felt, seen, and tasted, and Earth can use any of the five subtle elements (and so any of the five sense organs) to make an impression in your mind.

The 5 Karmendriyas: Organs of Action

There are also 5 organs of action (karmendriya is a compound of the word karma, which means “action”, and indriya, which means “organ”). The karmendriyas are how we interact with the world. Similar to the sense organs above, these represent the subtle organs in the mind, not the physical counterparts in the body. They are:

Vaak: Power of speaking

Paani: Power of grasping

Paada: Power of moving

Upastha: Power of procreating

Paayu: Power of excreting

Notice, the further up you go in the diagram of the 25 Tattvas, the more “subtle” the category gets. If you don’t understand what this means, don’t worry - we will go over the idea of “subtlety” later in the article on Prakriti and the three gunas.

Ok, let’s review what we’ve learned today. There are 5 Mahabhutas, or physical elements. The entire physical Universe, including the body, is made of these. It is just a framework, and like any other framework, there is no need to take it seriously. Yoga is not concerned with the outside world as much as it is about your “inner” world, and so this framework is only to help us connect the dots between the two.

There are also 5 Tanmaatras, or subtle elements (sound, texture, form, etc.). This is what we usually experience, and the physical elements evolve from these. We experience form and presume objects outside. We normally think that the object produced the form, but if we look closely, it is the experience of form that causes us to believe there is an object. Together with the Mahabhutas, this is what we normally consider to be “other” - or separate from “me.”

There are 5 Buddhendriyas, or organs of perception - these are not the physical eyes, ears, etc., but the capacity of seeing, hearing, etc. This is where the boundary of “me” usually begins. The Tanmaatras evolve from the senses because without eyes, there would be no light. The organs of perception can be considered the doorways to the mind.

Finally, we went over the 5 Karmendriyas, or organs of action, which are our capacities to speak, grasp, move, etc. These are the tools we have to interact with the world - our outputs.

Notice, there is no faith involved in any of this, simply noticing what is already in your experience.

Next time, we will go over the Manas, Ahamkaar, and Buddhi.

Until then, look at your experiences with this framework. Notice how you are quite literally creating your reality with every perception. The Universe depends on you, you are its creator, and this whole thing is a marvelous dance of you and not-you, together.