How do I become free from suffering?

The Four Yogas

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Welcome back! Last week, we went over the four Purushaarthas, or the four purposes of human life. To summarise, they were:

Dharma1: Doing the “right” thing

Artha: Money, power, wealth in general

Kaama: Sense pleasure

Moksha: Freedom from the cycle of suffering

In this week’s article, we will discuss the four paths to Moksha, or freedom from suffering. These are called the four Yogas, and are a framework to better understand the various “spiritual” paths that humanity has devised over the past several millennia. The four Yogas are not limited to the umbrella of Hinduism, but also include paths which may have never intersected with it, as we shall see in the following sections.

The word “Yoga” comes from the root word yuj which can mean to join (as in the English word “yoke”), but can also mean “to contemplate.”

The four Yogas are not mutually exclusive, but rather complementary to each other. However, each does serve certain purposes better than others. They are:

Bhakti Yoga: The path of love and faith

Karma Yoga: The path of unselfish action

Raja Yoga: The path of meditation (aka the “royal Yoga”)

Jnana Yoga: The path of knowledge (aka the “direct path”)

Bhakti Yoga

Bhakti means “love” or “devotion.” This is the most common path, and is characterised by devotion and faith to God. Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are examples of this path, where God is meant to be loved and followed, and faith is an imperative. The umbrella of “Hinduism” also has many Bhakti schools such as Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism, and many others. In the West, the Hare Krishna movement is an excellent example of this path. It is extremely powerful in its results, and exceedingly simple to follow.

However, it is not for everyone.

For many, especially in today’s day and age, faith is difficult. Simple questions cannot be answered logically without falling back on texts, or returning to the fact that faith is necessary. For example, asking a Christian “How do you know that God exists” will result in a series of responses which ultimately boil down to “because it says so in the Bible.” It is the same with other Bhakti paths, even in the “Hindu” traditions. There are many who have tried (and failed) to answer this question rationally, such as the first cause argument (all effects must have a cause, and so there must have been a first cause), or the argument of perfection (how could nature be so perfect without an architect), and many, many more. While these answers may be satisfying for some, for many, they are not. As a result, many people, especially educated youth, turn away from religion, assuming that there is nothing more that it has to offer. [Side note: If this paragraph made you feel uncomfortable, that’s good! You have identified a tightly held belief which you haven’t yet questioned. The goal of Yoga is to uncover the truth, and you have just found the first step on your journey - empty your cup!]

Having said this, there is a tendency in those who are not satisfied with the the path of faith to assume that those who believe in God are intellectually inferior. This is not the case. It is simply a matter of mental tendencies – some are able to hold faith better than others. Although it is not necessary for moksha, faith is an extremely useful tool, and can be a shortcut to freedom. If you have it, consider yourself lucky!

Astv’evam anga bhajataam bhagavaan mukundoMuktim dadaati karhichit na hi bhakti-yogamIndeed, among those who worship him, the Lord may grant Mukti (Moksha/liberation) sometimes, but rarely Bhakti. - Srimad Bhagavatam 5.6.18

Karma Yoga

Karma simply means “action.” Karma Yoga is the path by which one uses action to become free of action. One common Karma Yoga method is selfless service – doing action where the fruit is not going to be enjoyed by the actor. This is different from the Dharma-Purushaartha in that one can do the “right thing” without explicitly searching for freedom from the suffering it may bring. For example, one can spend their entire life trying to do good, but being attached to the fruits of their work, and thus suffering when the fruits do not arise. Karma Yoga is a discipline where the fruits of the action are given up. Further, it involves a close inspection of why we do “good” action in the first place. Ultimately, we realise and accept that our apparently “unselfish” action was selfish all along - it makes us feel good to do good work. This brings about a questioning of how to be truly unselfish. To illustrate this:

Jogi: Why do you want to be unselfish?P: So I can be a better person.Jogi: Why do you want to be a better person?P: (pauses) - because it will make me happy.Jogi: Is that not selfish?

Ultimately, once we are truly honest with ourselves, all unselfish action is also selfish in nature. Karma Yoga helps us to identify this, and bring us to a place of questioning the truth of our own nature.

In Bhakti traditions, this often takes the form of offering the fruit of one’s labour to God (e.g. “doing the Lord’s work” in Christianity, “prasaadam” in Vaishnavism, langar in Sikhism, etc.). However, it is not necessary to believe in God to be a Karma Yogi.

Karmanyivaadhikaaraste ma phaleshu kadaachanaMa karmaphalaheturbhurma te sango’stvakarmaniYou have the right to action, but never to its fruits.Do not let the fruits of your actions be your motive, and do not be attached to inaction.- Bhagavad Gita 2.47

In this verse from the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna lays out the basis of Karma Yoga. Doing action without attachment to the results. Notice in your own life when you may have worked with attachment to the result, and remember the anguish, anxiety and frustration it caused. Now compare that to a time when you were doing the work without worry of the results – remember the feeling of joy in this kind of action.

P: If I act without worrying about the fruit, won’t it be pointless? How will I ever get where I want to go?Jogi: There are many layers to this question, including the hidden assumption that there is somewhere to get to.“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow. They toil not, neither do they spin.”- Matthew 6:28Having said this, for most of us, this feels impractical. We have things to do, goals to meet, “success” and all of that.Taking this into account, consider your goals, know that your actions are driven by these principles, and then stop micromanaging yourself. Set the intention with your intellect, and then trust your body and mind to do what needs to be done.

Making a habit out of acting this way, one starts to notice that which does not move despite the intense activity that the body and mind undertake. This is how Karma Yoga leads to freedom. This last sentence may sound a bit esoteric, and there will be more on this later on as we dive into the nature of the Self.

Jnana Yoga

Jnana (pronounced “gyah-n” or “nyah-n”) means “Knowledge.” This is the path of inquiry into the nature of the Self by way of reading, listening, then doubting and questioning, and finally allowing it to settle in the depths of the mind (sravana, manana, nididhyaasana, respectively). This path involves numerous methods of systematic inquiry, and provides rational, logical, and intellectually honest answers to life’s big questions.

Ko’ham Kathamidam Jaatam Ko Va Kartaasya VidyateUpaadaanam Kimasteeha Vicharah So’yameedrishahWho am I? How was all this created? Who is its creator? What is its cause, its material? This is the way of inquiry.- Aparokshanubhuti 12, Shankaracharya

Many of the world’s religions have esoteric counterparts which fall into this category, for those who are more inclined towards logical inquiry than towards faith. For example, in the umbrella of “Hinduism”, Advaita Vedanta (Non-Dual Vedanta). Within Islam, Sufism. Within Christianity, there is the Gnostic tradition and other esoteric schools, in Judaism there is the Kabbalah, and in Buddhism there are the Madhaymaka Shunyavaada and Dzogchen schools.

Raja Yoga

Raja (pronounced “rah-j”) means “Royal.” This is the path of meditation, and is considered the “Royal road” to moksha because it provides direct experience rather than faith or philosophising. Again, most of the world’s religions have paths that fall into this category, but within Eastern traditions this path often has a strong textual and monastic tradition. For the purposes of this newsletter, we will be focusing on Raja Yoga as outlined by Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras.

As an aside, the modern use of the term "Yoga” refers to physical postures, or Asanas, also known as Hatha Yoga. This is only the third limb of the eight-limbed Raja Yoga of Patanjali. The postures are discussed in detail in texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika which, incidentally, explicitly states that the ultimate purpose of postural Yoga is Raja Yoga. Yoga, in its traditional meaning, is any set of practices that leads one to absolute freedom from dukkha, but also refers specifically to one of the six schools of orthodox Indian philosophy. It also refers to the final state of emancipation from the cycle of birth and death, skilled action, as well as the state of a completely controlled mind.

Even before freedom from all suffering, the path of Raja Yoga offers many benefits including stress reduction, improved moods, discipline, and general well being. However, it is important to note the context and ancient traditions out of which these practices stem.

Practicing meditation certainly provides benefits, but if done without the proper context, it can eventually lead to feelings of detachment, disassociation, and fear stemming from what is often termed “ego-death”, which is in fact the explicit purpose of these practices. Done properly however, it can bring about feelings of immense bliss and peace.

How the four Yogas play together

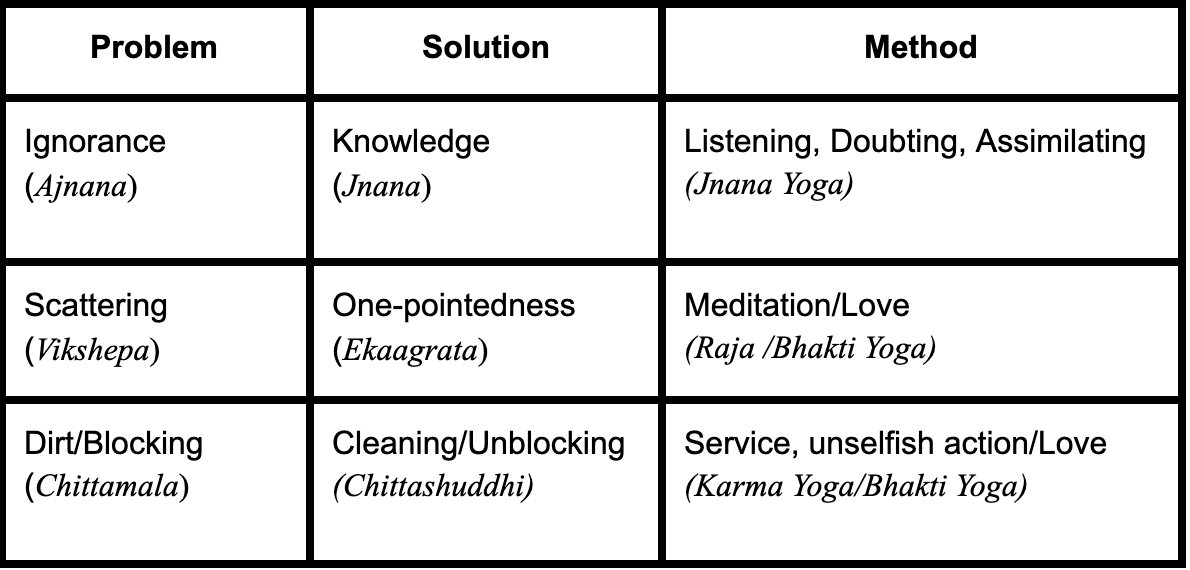

While each of the four Yogas is sufficient for Moksha, they each have particular strengths in terms of solving the three main problems that block one from knowing themselves as they truly are. Moksha is not something to be achieved, but rather your natural state. You are already free - always were and always will be. The problem is that we don’t know it. We feel like a mind trapped inside a body, somehow dropped into a vast, uncaring Universe - the purpose of Yoga is to clear up the blockages that keep us feeling that way, and help us to clearly see the Truth.

The traditional example is that of a farmer who wants to irrigate their field. The farmer will go to the bank of the river and remove some soil to allow the water to flow where they want it to flow. In this way, Moksha is like the water – it is already there, and flowing freely. All you need to do is remove the soil that’s blocking you from Knowing your Self as you truly are. There are three main blockers:

Chittamala: Mental “dirt”

Chittavikshepa: Mental “scattering”

Ajnana: Ignorance

Chittamala: Mental “dirt”

Chitta roughly means “mind”, and mala means “dirt.” Chittamala includes things like anger, jealousy, pride, delusion, cravings, sloth, etc. that lead to feelings of sadness, anxiety, and dejection – dukkha. The solution to chittamala is chittashuddhi – simply, mental “purity” which does not mean that you never have a dirty thought, but rather that the mind is no longer focused on the continuity and well-being of the separate-self (i.e. the identity that you have built up over your lifetime, generally tied to mind and body) over others.

The methods that are best for achieving chittashuddhi are Karma Yoga and Bhakti Yoga.

Notice, one does not need to believe in God to achieve chittashuddi. In fact, in the Advaita tradition (which a lot of these writings will be based on), blind belief in God without doubt or questioning can even be a hindrance to progress.

Chittavikshepa: Mental “scattering”

Vikshepa means “scattering.” This phenomenon is well known to all of us who relate to this meme, courtesy Reddit:

If the mind is scattered, it leads to feelings of sadness, boredom, anxiety, and dejection. Notice, we often speak of boredom as the cause of a scattered mind – there is nothing exciting enough to focus on, and so we consider ourselves bored.

Here, it is exactly the opposite – boredom is the result of a scattered mind, not its cause.

The solution to chittavikshepa is chitta-ekaagrata – which just means “one-pointedness of mind.”

The methods that are best to achieve this are Raja Yoga and Bhakti Yoga. Raja Yoga includes (but is not limited to) things like mindfulness and vipassana, which we will discuss more later on in this series, from a Yogic perspective.

This blocker is a level above chittamala – if there is anger, jealousy, etc. in the mind, it will naturally scatter and will be more difficult to focus. As a result, the suggestion is to first tackle the chittamala and then bring attention to focusing the mind. Raja Yoga deals with both these categories. A clear symptom of one who has tried to focus the mind before cleaning the dirt is when someone says “I find it difficult to meditate” or “I can’t sit down and focus.” The tendency for the senses to go outwards towards objects of the senses leads to a mental scattering that is difficult to bring under control without using the faculty of the organs of action.

Ajnana: Ignorance

Ajnana (pronounced “uh-gyah-n” or “uh-nyah-n”) does not refer to just any ignorance, but specifically the ignorance of the nature of the Self. Notice, I use the word “Self” with a capital S to differentiate it from what we normally refer to as self (i.e. mind, body, identity). For those of you acquainted with Buddhism, in Buddhist terms, this would be the same as one who does not recognise the truth of anatta or non-self.

The solution to Ajnana is Jnana, or Knowledge, and the method is Jnana Yoga.

For many who are introduced to Jnana Yoga without first having solved the first two blockers above, the symptom is that of “understanding it intellectually” but not “absorbing it.”

To summarise, here is a table:

An analogy to help with this is that of unlocking a door. You arrive home late one night, stumbling through your hallway in the dark. The lights are off, and it is difficult to see the door, let alone the key-hole. This is chittamala. You turn the lights on so you can see clearly. This is chittashuddhi.

Your hand is shaking (perhaps it is cold outside), and so it is difficult to put the key into the key-hole. This is chittavikshepa. You steady your hand. This is ekaagrata.

Finally, you don’t have the key, and there is no way to open the door. This is ajnana. Your friend, standing next to you this whole time, hands it to you. The key is jnana. With your now steady hand, using the light to see the keyhole, you put the key in and open the door. This is moksha, or freedom.

What’s Next

In this newsletter, we will start by focusing on Raja Yoga. The goal will be to provide you with frameworks and techniques to apply both in your day-to-day life, as well as in seated meditation so as to clear the mind of dirt/blocking, as well as to focus it. Imagine your mind as a river – right now, it is muddy and turbulent. The goal will be to first clear it so it is clear but turbulent, and then to calm it. To do this, we will use frameworks presented by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras, and go through them in an order that makes sense for practical application to our day to day lives.

Next time: Your senses create the world: Primal ignorance and the 25 Tattvas (Part I)

The word “Dharma” as used here, is not to be confused with the usage in Buddhism, where it is used to connote the method that the Buddha laid out to achieve Moksha. The Buddha Dharma (aka Buddhism) includes methods from all the Yogas mentioned above, including a form of Bhakti Yoga where one surrenders to the Buddha, the Sangha, and the Dharma, rather than God (Buddhism is atheistic).

Thank you Kunal! 🙏 That is a very clear explanation of the 4 yogas. It seems that Bhakti yoga may be the surest path to moksha, but it requires faith and that is something that seems innate. Is faith truly something that people are born with or can it be cultivated either through direct mystical experiences or even through something that appeals to the logic like Jnana Yoga? And if faith can be cultivated then is it considered indirect and therefore inferior in some way compared with faith that is innate? Somehow it seems that when one is born with shraddha, it is always better than when one adopts it later in life.