Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Imagine your mind as a lake. When the lake is calm, you can see the bottom easily, but when there are ripples, the bottom is harder to see.

Now imagine that the water is muddy. The bottom is nearly impossible to see, regardless of the ripples in the lake.

In this analogy, the ripples are vrittis - the 5 types of mental modifications that we discussed in last week’s article. This week, we will talk about the dirt.

वृत्तयः पञ्चतय्यः क्लिष्टाक्लिष्टाः॥Vrittayah Panchatayyah KlishtaAklishtahThe vrittis are of 5 types - they can be coloured or uncoloured.

- Yoga Sutras 1.5

In Yogic Psychology, the 5 types of vrittis can either be coloured or uncoloured. These colourings are called kleshas, and are the cause of all the mental suffering we experience.

Remember, Sanskrit is a polysemic language, which means that a word can have several meanings. The word “klesha” comes from the root “klis” which can mean colour1, affliction, poison, burden, or pain. All of these are correct in this context.

There are a total of 5 Kleshas, and, in terms of their strength or influence, they can be severe, weakened, interrupted, or dormant at any given moment in one’s inner life. The goal of Yoga is to first weaken the influence of the kleshas, and finally to put them into a dormant state so they can be destroyed. The classical example is that of a seed which, once burned, will never again sprout.

Normally, these kleshas are very active in our lives and cause feelings like jealousy, anger, pride, vanity, hatred, and several other emotions that disturb the mind. By weakening your kleshas, you will find that your mind becomes calm and peaceful, and your inner joy will shine forth. Don’t take my word for it - try it for yourself!

The 5 Kleshas are:

Avidya: The Primal Ignorance

Asmita: “I am”-ness

Raag: Attraction

Dvesha: Aversion

Abhinivesha: Fear of discontinuity

Avidya: The Primal Ignorance

Look around you right now. You likely see a laptop or a phone, the walls of the room you’re in, your own hands, and maybe some other physical objects. You may hear some sounds - maybe the ventilation in your apartment, traffic on the street, birds in the trees, the wind, and your own breathing. In addition to the physical objects around you (including your body), you likely are experiencing a voice in your head reading these words, the feeling of understanding the meanings, the wavering of your attention, the level of energy in your body and mind, and a whole host of other objects - internal and external.

If you examine closely, you will find that these “objects” are not really objects at all, but rather just a cluster of individual perceptions to which we have assigned a name. For example, what you call a laptop is a cluster of individual, momentary sight-perceptions, touch-perceptions, sound-perceptions to which we have assigned a name - “laptop.” Similarly, what we call a “body” is a cluster of individual perceptions to which we have assigned a name.

To make this clearer, let’s take a look at the image below. What do you see?

Avidya is just like in this Rorschach plot - right now it’s a meaningless (and beautiful) mess, but if you look at it long enough, you start to project meaning onto it - especially if you want to discuss it with someone else. The tendency to conceal the underlying reality and project meaning is Avidya.2

Take a look at the meanings projected onto the plot above. I can even make up a story about them:

A fisherman put his spear into the river. Seeing this foreign, powerful object, all the river-creatures decided they should worship it. The frogs got up really close to it because they had powerful legs, while the fish swam as close as they could, and the crabs carried some leaves to fan the spear with, as a method of worship. Seeing the gathering of the river-creatures, the birds decided to dive in and have a look for themselves. However, as it started to get crowded, the frogs got a bit too close to the spear, and it cut them. As the spear cut through their flesh, they bled, and three droplets of their blood spilled downward into the water.

Now really speaking, there is no frog, fish, spear or leaves. We projected those onto the plot that did not have objects intrinsic to it. We even separated out the background (the water) without giving it a second thought! But taking the story seriously, we could start to ask questions like “why didn’t the fish get there first?”, “how were the birds able to stay underwater for so long?” or “how did the blood fall downwards in such perfect droplets, and not diffuse into the water?”. These questions can be answered, of course, using the framework that we projected onto the plot (frogs, fish, leaves, river, etc.), but really speaking, the questions are meaningless, and so any answer would be just as fictional as the objects themselves.

Notice, the projections work through language - we create objects by creating a symbol (e.g. a word, or an idea), and then acting as though that symbol is fundamentally somehow real.

These names and symbols are, of course, tremendously useful to us - we can use them to communicate with each other. However, the problem arises when we start to take the names seriously, as though the objects are real in themselves, and not just a collection of individual perceptions assigned a name for convenience, and by convention. This is especially problematic when it comes down to the mind, body, and idea of “me.” Once there is a “me”-idea, questions such as “what happens when I die?” or “where was I before I was born?” can arise. However, really speaking, just like in the example of the Rorschach plot above, these questions are meaningless because the idea of “me” is itself a conventional fiction.

This clustering of perceptions into objects, and then taking those conventional labels seriously is called “avidya” (pronounced uh-vid-yaah) or ignorance. It is the underlying cause of Karma, of the idea of the individual sentient being (aka the jiva), and so the ultimate root of all suffering. Specifically, it results in four behaviours, or confusions:

Confusing the impermanent as permanent

Confusing the impure as pure

Confusing that which causes inevitable suffering as something that may cause happiness

Confusing the non-self for the self

The removal of avidya is called by many names - Moksha, Nirvana, Jnana, Salvation, Enlightenment, Awakening, Freedom, and many more across various traditions. In terms of Karma, the removal of avidya is the complete freedom from Karma.

A traditional example likens avidya to a field in which all the other kleshas grow. If avidya is removed, all the other kleshas disappear with it. Said another way, first we selectively cluster the perceptions, then we give these clusters names. We then take the clusters seriously, and finally start getting attracted to some clusters, averse to others, etc. This final attraction, aversion and so on are the other kleshas, and they cannot exist without the fertile ground provided by avidya.

Asmita: “I am”-ness

Have you ever noticed that when someone takes your phone away from you, even briefly, you feel a slight sense of anxiety? If not, have you ever noticed a sense of anxiety when someone is about to bump into your car on the street? If not, let’s try another example - when someone insults your body or your behaviours, do you feel bad?

Asmita (pronounced uh-smih-taah) literally means “I am”-ness. When we consider something as “me” or “mine”, suffering is the inevitable result. This is true for anything at all - it could be a physical object out there, it could be the body, it could be your mind, an idea you had, or even things like your job, your financial status, your house - anything that you consider as belonging to “you”. This feeling of “mine” or “me” that we project onto objects and sensations (ie. vrittis) is called Asmita, and is the second colouring on the list because all the colourings below stem from it. Asmita stems from Avidya, and the other kleshas below stem from Asmita.

Asmita is not to be confused with Ahamkaar, which is specifically a movement of mind which takes credit. While Ahamkaar is a function of the mind, Asmita is a colouring on existing vrittis that may or may not be present. For example, if you see a cloud in the sky, Ahamkaar is active (in that it helps to create a distinction between you and the perception of the cloud, and creates a unified sense of “I” as the perceiver of the cloud), but Asmita is not (that is, you don’t feel like the cloud somehow belongs to you).

दृग्दर्शनशक्त्योरेकात्मतेवास्मिता॥DrgDarshanShaktyorEkAatmataEvaAsmitaaaAsmita is when the Seer and the power of seeing (ie. Buddhi) are taken as one.

- Yoga Sutras 2.6

In terms of Yoga psychology and the 25 Tattvas, Asmita is defined as the confusion of the Purusha (Self) with the Buddhi (intellect). All our experiences are mediated by the Buddhi, and so it is not surprising that this is a deep-rooted klesha. However, when we inspect closely, we will notice that the Buddhi (unlike the Purusha) is constantly changing. As an example, there was once a time when you did not understand calculus, then there was a time when you did, and perhaps now you no longer understand calculus. This is true for any understanding - the buddhi, being the seat of understanding, is thus seen to be in constant flux.

We know that asmita is active when we feel that we are the body, or that we are the mind, and so say things like “I am thin”, “I am fat”, “I am happy”, “I am sad”, or even “I am awake” or “I am tired.” Specifically though, it is the “I am”-ness before any specific identities (like thin, fat, happy, sad, etc.) have been taken on. It is similar to avidya above, except it is specifically focused on what we consider to be “me” or “mine.” Avidya results in asmita, and from asmita flow the following kleshas on the list.

Raag: Attraction

Imagine you just took a bite out of a delicious dessert - one that you have never tried before. There is a feeling of pleasure that permeates the mind. Now watch closely, what happens immediately after? There is another movement that pulls you towards taking another bite. This second movement is raag.

As an example, I love chocolate chip cookies from Starbucks - especially when they are warmed up just enough to make the chocolate chips melt. In terms of kleshas and vrittis, this means that the vritti of the warm chocolate chip cookie is coloured by the klesha of attraction (raag), because I am drawn to the cookie due to a memory of a past pleasure.

सुखानुशयी रागः ॥SukhaAnushayi RaagahRaag (attraction) follows pleasant experiences.

- Yoga Sutras 2.7

This attraction or attachment is not an issue of morality - it’s just a fact of life. We are all attracted to some things more than others, and the level of attraction changes over time. It is a natural tendency of the mind, and should be viewed in a playful way - the way you might view a child who puts their hand in the cookie jar. The key is to notice the attraction as it arises. If we do not notice it, it pushes us to act, and so we get stuck in patterns that may be unwanted.

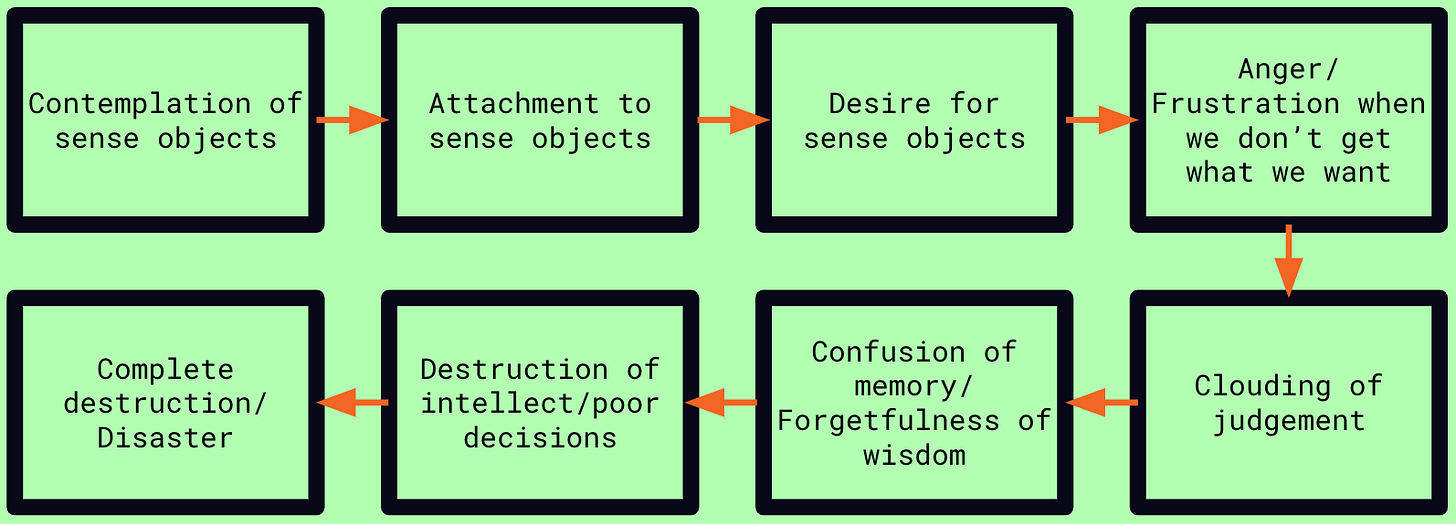

The Bhagavad Gita describes a chain of events that stem from the contemplation of sense objects:

ध्यायतो विषयान्पुंस: सङ्गस्तेषूपजायते | सङ्गात्सञ्जायते काम: कामात्क्रोधोऽभिजायते ||क्रोधाद्भवति सम्मोह: सम्मोहात्स्मृतिविभ्रम: | स्मृतिभ्रंशाद् बुद्धिनाशो बुद्धिनाशात्प्रणश्यति ||Dhyaayato VishayaanPunsah SangasTeshuUpajaayateSangaatSamjaayate Kaamah KaamatKrodhoAbhijaayateKrodhaatBhavati Sammohah SammohatSmritiVibhramahSmritiBhranshaad BuddhiNaasho BuddhiNaashaatPranashyatiBy contemplating the objects of the senses, a person develops attachment to them.

Attachment leads to desire, and desire leads to anger.

Anger leads to a clouding of judgement, and a clouding of judgement leads to a confusion of memory.

Confusion of memory leads to destruction of the intellect, and destruction of the intellect leads to complete ruin.

- Bhagavad Gita 2.62-63

On the other hand,

रागद्वेषवियुक्तैस्तु विषयानिन्द्रियैश्चरन् |आत्मवश्यैर्विधेयात्मा प्रसादमधिगच्छति || 64||RaagaDveshaViyuktaisTu VishayaanIndriyaisCharanAatmaVashyairVidheyaAtmaa PrasaadamAdhigachchhatiA person free from the influence of raag and dvesha, with control over their mind, even while using the objects of the senses, attains mental peace and clarity.

- Bhagavad Gita 2.64

We can be attracted to any type of vritti - a perception or other knowledge, memories, ideas, sleep, and even to illusions. Just like with the other kleshas, the more the colouring of raag, the stronger impression it will leave on the mind.

Dvesha: Aversion

Dvesha means aversion, and, like the other vrittis can vary in terms of intensity - we are more averse to some things than to others. For example, you may dislike brussels sprouts but may still eat them, but if you are given a bowl of pig’s blood, you may not even touch it. This is how kleshas work in degrees.

Something to note here - and it is true for the other kleshas as well - things in themselves are neither attractive nor unpleasant. It depends entirely on the kleshas present in the mind of the observer. We often are deluded by this notion thinking that a person is objectively more attractive than another, or that one food is objectively better than another.

To make this clearer, one person may dislike brussels sprouts, while to another, it may be one of their favourite foods. One person may love Britney Spears, while to another her music may sound grating to the ears. Similarly, one person may find someone very beautiful, while another does not feel the same way. This says nothing about the objects themselves, but rather about the kleshas present in the mind of the observer.

P: If my mind has a dvesha colouring on the vritti of brussels sprouts, isn’t that the same thing as saying it has a raag colouring on the vritti of the absence of brussels sprouts?

Jogi: Sort of. The absence of brussels sprouts may not be as attractive to you as the degree of your aversion, but it is true that raag and dvesha are two sides of the same coin. They go together in this way. Being attracted to something includes some degree of aversion to its absence, and conversely being averse to something includes some degree of attraction to its absence.

दुःखानुशयी द्वेषः॥DukhaAnushayi DveshahDvesha (aversion) follows unpleasant experiences.

- Yoga Sutras 2.8

Just like raag, the basis of dvesha is a past experience (specifically, pramaan) of pain caused by the same medium. For example, the reason for my aversion to touching a hot stove is a past experience of having touched it, a past inference of pain (e.g. I saw someone else get burned), or past trusted testimony of pain (e.g. someone having told me previously of pain caused by touching a hot stove).

Sometimes, raag and dvesha are not clearly present, but are active in the form of samskaaras or impressions in the mind. For example, you may not be aware of your aversion to a particular style of TV show, but you always scroll right past this genre when looking for something to watch on Netflix. This is also true in terms of racial or other biases towards people. You may not be aware of your bias towards a particular race or religion, but your actions may still be driven by a dvesha or raag-klesha in the form of a samskaara (impression) in your mind. Searching for the cause of your biases may not be as fruitful as an investigation to find out what your biases are, and counteracting them consciously.

In addition to meditation and close inspection of the mind, tests like the implicit bias test can help to uncover some of these raag and dvesha impressions so you can consciously counter them in your day to day life.

Abhinivesha: Fear of discontinuity

Abhinivesha is a fear of discontinuity, and it is especially apparent in the innate fear of death or clinging to life.

Have you ever heard someone say “that’s so you” or “I really think you would like this”? This is an example of how we use the kleshas above to strengthen the sense of false identity with the body-mind complex. Liking or disliking certain things, and identifying with some things more than others is the basis for our created identity. The problem arises when we start to take this seriously and really think - “This is who I am.”

Once this identity exists, there is now a desire to protect it. In the examples above of the anxiety and pain we feel when someone insults our body, our minds, or even our possessions or ideas, while the initial identification as “me” is Asmita, the fear and anxiety we feel when the “me” is threatened is abhinivesha. The most apparent example of abhinivesha is the feeling of fear when one is faced with physical death. However, that is not the only time this klesha can be present.

Have you ever felt anxious about leaving your job? This is abhinivesha in action. You will notice that the anxiety increases with the degree of identification. How would you describe yourself at a dinner party? “Hi my name is so and so, and I am a manager at this company.” If this is your method of describing yourself, this is likely a sign of identification. If this identification is strong enough for you to describe yourself to those you have just met, changing this identity will likely cause a strong sense of fear or anxiety.

Another example - when you move from an apartment or a house that you see as a part of your identity. Perhaps you have lived there for a long time, and have had a lot of friends and family visit and compliment it. If you took these compliments on as a part of your identity, you will find a resistance to moving - this is abhinivesha.

Even in writing this series of articles, if I were to add this newsletter on as a part of my identity, if for some reason I had to stop writing it, it would result in mental suffering. This is abhinivesha.

The funny thing is, we feel a deep sense that we are obligated to maintain a continuous identity. This is especially apparent in resumes, college applications, and social media profiles. We feel that we must build a consistent story. While some of this may be based on evidence (and would thus be categorized as raag or dvesha), there is a part of this desire for continuity that is innate. This innate part of the desire for continuity is an example of abhinivesha.3

As an aside, through meditation there can arise a feeling of deep fear upon seeing clearly the illusory nature of the separate self (aka “ego death”). This fear is abhinivesha in action.

P: Isn’t this just an aversion - dvesha for discontinuity or raag for continuity?Jogi: Excellent question. Notice, dvesha and raag are based on a memory of past suffering or pleasure, respectively. Specifically, this means that we have a previous pramaana (direct perception, inference, or trusted testimony) of pleasure or pain that results in a tendency for attraction or aversion. Here however, the fear of discontinuity need not be due to a prior experience. For example, you are afraid of death even though you have not directly experienced death before.

P: But I have heard that death is painful, isn’t this trusted testimony?Jogi: Even a baby or a newborn worm displays signs of fear when faced with death. This cannot be explained by trusted testimony. You may have a dvesha in addition to the innate abhinivesha, but we can see from the examples of the worm and the baby that there is also an innate abhinivesha - flowing on its own momentum, without a need for a past experience.

स्वरसवाही विदुषोऽपि तथारूढ़ोऽभिनिवेशः ॥SvaRasaVaahee VidushoApi TathaaRoodhoAbhiniveshahEven in the advanced Yogi, as if flowing on its own momentum, is a firmly established [clinging to life or resistance to change/death, called] Abhinivesha.

- Yoga Sutras 2.9

Ok, cool, but what do I do about these kleshas?

ध्यानहेयास्तद्वृत्तयः ॥DhyaanaHeyaasTadVrittayah[The method] to overcome these [klishta] vrittis is Dhyaan [meditation].

- Yoga Sutras 2.11

Meditation is the method to overcome the kleshas, once they have become subtle (we will discuss what “meditation” is in more detail in future articles). At first, however, meditation can be difficult due to the turbulence and muddy nature of the Yunjamaana’s (beginner Yogi’s) mind.

The first step is to simply notice the kleshas in your daily life using the framework presented here. The next step is to make them more subtle - to systematically uncolour the mind. There are several methods to do this, starting with our daily interactions with the world to eliminate the obstacles, then moving on to our interactions with other people, and finally, when we are ready, a method to train the restless mind.

Over the next few weeks we will go over some methods, systematically.

At the end of each article will be a suggested practice to cultivate for the week. If you are so inclined, you can try it for yourself and see how it impacts your mind. Throughout, I would suggest keeping a journal or a notepad so you can keep track of your progress and practices that work or don’t work for you.

As always, please don’t hesitate to reach out or use the comments section below for any questions, objections, clarifications, or feedback.

Next week: Obstacles, Accompaniments, and One-Pointedness

While the translation “to colour” brings across the meaning more viscerally, a more common translation is “to obscure.”

Specifically these are the two powers of Maya - Aavarana Shakti (the power of concealment) and Vikshepa Shakti (the power of projection). The relationship between Maya and Avidya is like a forest to an individual tree, or like a lake to a drop of water.

Several traditional commentators use the example of the fear of death in a newborn baby or a worm in order to infer reincarnation - that is, we cannot explain the fear of death unless there was a previous experience of the pain and suffering of death. For the purposes of this series there is no need to believe in reincarnation - in fact, don’t believe anything you read here without passing it through your own judgment, experience, and experimentation.