We see the world through a curtain of thought

The lower and higher perception: The confusion between word, meaning, and idea

Thanks for reading Empty Your Cup!

Over the next few weeks, I will be compiling questions from readers. If you have any questions (seriously, any questions at all), please put them here, and I will answer them to the best of my ability in the coming weeks. All questions of all levels are welcome, and if you prefer, you can submit your questions anonymously.

Again, here is the link.

🙏🏽

Kunal

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Last week, we went over the four levels of Samaadhi, and the importance of sticking to a single aalambanaa, or support, for meditation.

As a quick recap, while exploring the breadth of meditation - selecting different objects - can be helpful in order to find what works best for you, ultimately it doesn’t matter as much as the depth of meditation where we move deeper into a single object to uncover the nature of reality.

We discussed the four levels of samprajnata samaadhi:

Vitark: Samaadhi on the gross aspect of the object

Vichaar: Samaadhi on the subtle aspects of the object

Aanand: Samaadhi on the sattva aspect of the antahakarana used to grasp the object

Asmitaa: Samaadhi on the sattva aspect of the buddhi used to grasp the object

These are characterised by which of the three aspects of knowledge - the graahya (the object of knowledge), the grahana (the instrument of knowledge), or the grahitr (the knower) - is used as a support for awareness.

These four samaadhis are further broken down into levels of engrossment in an object known as samapattis.

Samapatti is the state of mind where there is no veil of thought colouring the object of perception.

Last week, we discussed how normally, when we look at an object, we look at it through a curtain of memories, imaginations, words, ideas, and so on. Samapatti is when the mind is so engrossed in the object that it takes on the form of the object entirely, without any additions, just like a clear crystal takes on the colour of any object placed near it.

P: I get it, but what’s the point of going deeper?

The stepwise process of samaadhi (and really all of Yoga) can be seen as a systematic march from outside to inside, from the external world to the Self. At every stage, starting with the first limb, the Yogi lets go of a layer of their being, moving their attention deeper inward, until eventually the Self shines alone.

Once this final state, known as asamprajnaata samaadhi or nirbeeja samaadhi, or simply as anya - “the other [Samaadhi]” - is stabilized, the Yogi knows, without a shred of doubt, that they are neither the body, nor any aspect of the layered mind, and thus becomes free from any suffering experienced thereof.

P: Isn’t this just spiritual bypassing?

Jogi: Not at all. It is not as though the problems of the world can then be ignored. Rather, the extreme mental clarity that comes from these states allows the Yogi to see truth more clearly, and deal with them more effectively than they would have through a veil of vrittis and kleshas. Additionally, they can use this clarity to reduce the suffering of others.

P: How can I attain these states?

As discussed previously, Samaadhi is not something you do, but rather something that happens. Like Dhyaan, is not a result of a pratyaya - an act of cognition - but rather the result of samskaaras, or impressions.

In practice, this means that while the Yogi cannot simply will themselves into Samaadhi, they can create a fertile ground for the mind to go into Samaadhi more easily. More specifically, this is done by reducing the vyutthaana (outgoing or gesticulating) samskaaras, and increasing the niruddha (mastering, ceasing, or controlling) samskaaras. More on this here:

Last week, we went over, at a high level, the progression through the various samaadhis, and what each step means. This process is known as pratiprasavah (प्रतिप्रसवः), or “involution.” It can be compared, in a sense, to a telescope being pulled into itself, one layer encasing the next.

I remember as a child, sitting in the back seat of a car on a rainy day, looking at the outside world through the window. I noticed that if I focused on the outside, the window and the raindrops would become blurry. On the other hand, if I focused on the raindrops trickling down the window, the outside world would go out of focus. However, if something outside caught my eye, my attention would immediately shift to the outside world, and I would lose track of the tricking raindrops.

Each level of Samaadhi is like this, except with several more layers.

As the Yogi moves in through each layer, the outside layer goes “out of focus”, and can be dropped away. However, unless vairaagya is strong, the mind will automatically flow outward, and the samaadhi will become unstable.

This is why the earlier limbs of Yoga are important - they stabilize the mind by increasing niruddha samskaaras and decreasing vyutthaana samskaaras.

Today, we will go over a key concept in Yoga - the distinction between word, meaning, and idea - with the goal of (next time) understanding the distinction between the first and second samapattis - savitark and nirvitark - in more detail.

Keep in mind as we go through this and the following stages that these descriptions are only one way of mapping out the territory of the mind. On a map, a mountain looks like just a triangle. If we were to look for a triangle when we got to the mountain, we would miss the mountain entirely. In this way, take these descriptions for what they are - pointers - and avoid the temptation to put these states on a pedestal.

Word, meaning, and idea

Try this exercise: Imagine your mind as a calm lake. Now say the word “cow” out loud.

Now do it one more time, but this time pay close attention to what happens in the mind.

What did you find?

Most likely, as you said the word, a rough image of a cow appeared in the mind, like a ripple in the lake. It may not have been visceral, but it was a rough mental movement that represented your idea of a cow. Then, as the sound vibrations became weaker, and the memory of the sound faded, the rough mental image also began to fade back into the mind, as a ripple fades back into a lake.

Now look at this image.

Did you notice the quietest whisper of the word “cow”? What about the subtle mental classification “this is a cow”?

Notice, there are three things involved here:

Shabda: Word

Artha: Meaning, or signified object

Jnana: Idea/Knowledge, or seed of a generic mental pattern

These three - word, meaning, and idea - are distinct mental occurrences. Yet, in our day-to-day lives, we mix them up, and do not make a distinction between them. As a result of this confusion, we end up seeing the world through a filter of our own knowledge and patterns of thought, rather than seeing things as they are.

The first step, then, to seeing things as they are, rather than through the curtain of thought, is to clearly understand the distinction between word, meaning, and idea.

Shabda: Word

The word “cow” is just a sound - a particular pattern of vibration of air molecules, created by a particular pattern of movement in the vocal cords, which lead to a particular pattern of vibration of the ear drum. There is no actual cow in the sound. This sound is shabda (शब्द, pronounced shub-duh), literally “word”.

Different languages can use different words to represent the same object.

For example, while in English, the sound “cow” represents a cow, in Hindi, it is “gai”, whereas in Spanish, it is “vaca.” The fact that these sounds represent the object is a matter of convention, built over time. We could, for example, collectively decide to refer to cows as “hoohos” or “binpats”, and this set of sounds would do just as well.

Given this, we can see that there is nothing special about particular words that points to the objects they refer to.1 Meaning, or reference, therefore, must come from a combination of sound and something in the mind of the perceiver.

Let us investigate.

Once the vibrations in the air hit the ear drum, there is no guarantee that the perceiver will understand the meaning. For example, one could say the word “vaca” to a person who does not speak Spanish, and they would not be able to understand what it referred to unless the object is pointed out.

However, once the object is pointed out, they can make the connection between the sound and the object referred to.

But this is not enough. They must also be able to distinguish the object from its background or surroundings.

To make this clear, let us take an example.

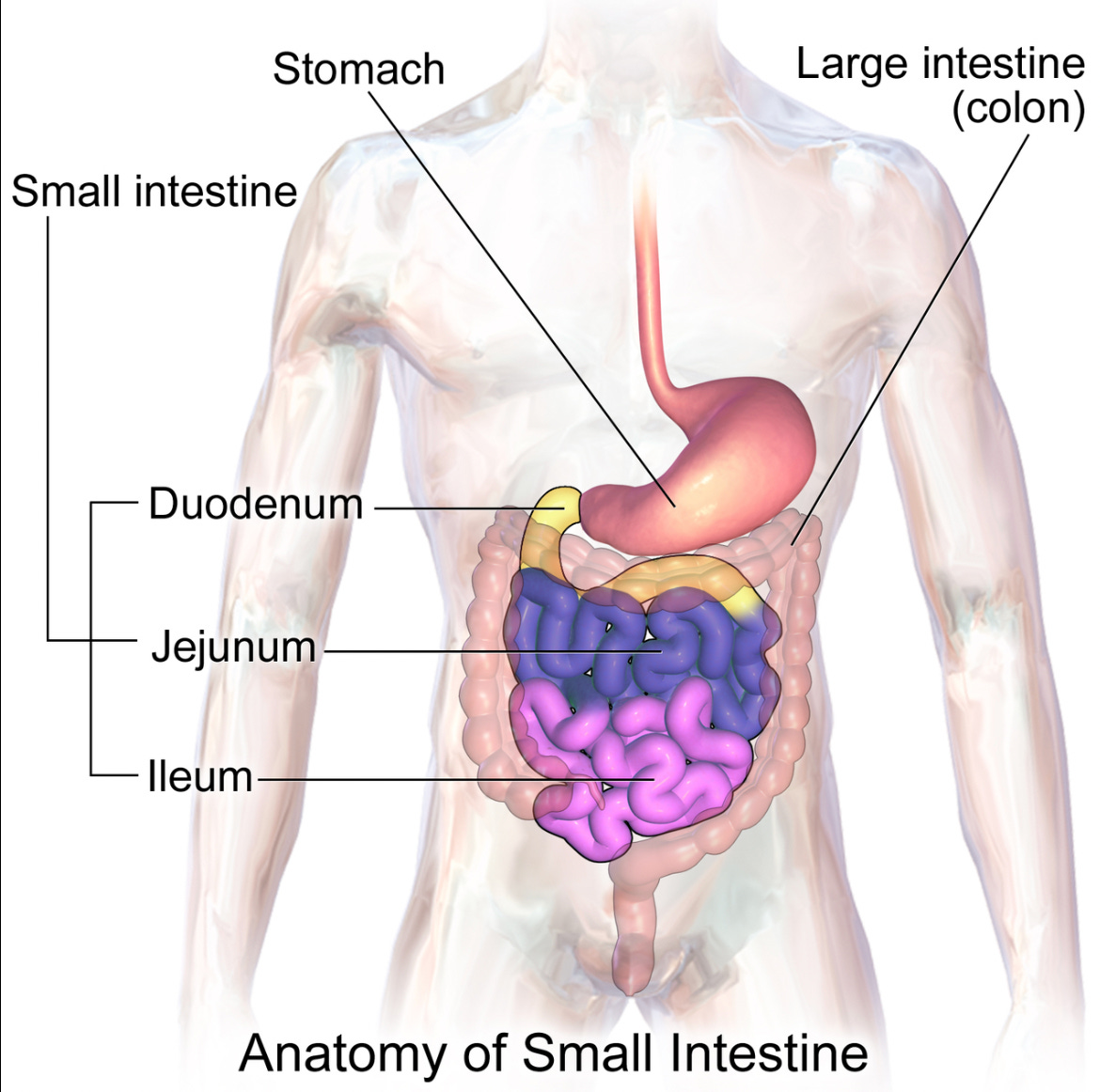

Consider someone who has not studied the anatomy of the human body. They may know some basics - such as “knee”, “thigh”, “mouth”, “stomach”, etc. - words used in day to day language - but they may not know more specific words such as “duodenum”, “jejunum”, or “ileum”

Now as we have seen, if they were to understand the meaning of these words, the objects they refer to would have to be pointed out. However, objects are ultimately defined by their boundaries. Therefore, unless the boundaries are clear, the meaning of the words cannot be understood.

Using the example of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, we can provide some more detail, by saying that they are parts of the digestive system. But this is not enough, since they could very well be in the mouth, or the stomach, or the liver.

We could then try to be more clear, by saying that they are parts of the small intestine. Now we are getting closer, but the meaning of the words is still not clear. Are they the technical names for the outer, middle, and inner layers? Are they referring to some interior portions of the small intestine?

As we can see, the mechanism we use to make the meaning of words “more clear” is to distinguish the referent from other objects, through means of classification into categories.

That is, by saying that the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum were parts of the digestive system, we are saying that they are not parts of the circulatory system, the nervous system, the skeletal system, and so on. Then, by saying that they are parts of the small intestine, we are saying that they are not parts of the stomach, the mouth, the liver, and so on.

Finally, we may show a diagram like this:

Here, we see the boundaries between the three, and so we can finally understand the meanings of the words.

The reason we understand the meanings of the words at this point, and not earlier, is because we can now clearly see the boundaries that distinguish the objects from their surroundings.

It is through this method of exclusion that the meaning of a word is understood.

By saying what a word means, we are also saying what the word is not.

Both what it is, and what it is not, are necessary in order for the connection between word and meaning to become clear.

Now that we understand what these words mean, the next time we hear the same combination of sounds (either through gross sound or subtle sound in the mind), memory permitting, we will understand the object that they refer to, even when the object is not in front of us. This is how shabda turn into jnana - idea or knowledge.

Jnana: Knowledge, or idea

Back to cows.

When the eardrum vibrates in this particular way, it generates a signal that reaches the brain, and this awakens a pre-existing pattern in the mind. This pattern is generic, and referential. That is, it is not specific to a particular cow, but rather some sort of loose amalgamation of what you know a cow to be.

Additionally, it is not an image, per se, but rather a pattern of mental movements that represents the generic aspects of the class called “cow.” This pattern arose from a seed in the mind, which became active when the word was heard. This seed is jnana (ज्ञान, pronounced gyaah-nuh) - the “idea” of a cow.

The presence of this jnana is the reason that you are able to recognize the fact that these images are all of cows - even though the specific cow in each image is different from the others.

With the example of the jejunum, duodenum, and ileum, we now know that there is a relationship between the word and the object referred to. This knowledge is stored as a seed in the mind. When the particular combination of sounds occurs again - in the mind or in the external world - this seed sprouts, and a rough mental image appears.

It is important to note that this mental image is not a specific cow or small intestine. Rather, it is a generic mental image that can fit any cow or small intestine.

The boundaries here are fuzzy - that is, if the object that one perceives, or the word that one hears, falls slightly outside of the boundary of the original object, it can still be recognised as belonging to the same class or category. Then, the new aspects are added to the class for future recognition. In this way, jnana is an ever-growing seed, accumulating nutrients from its surroundings.

Artha: Meaning, or referent

Finally, there is the actual cow in the picture.

This is a visceral image, also appearing within the mind, but is a specific cow. It is not referencing a cow, it is the very cow being referenced. You know it is a cow because it corresponds to the mental pattern - the jnana - of what you know a cow to be. This cow - the object referred to by the word and the idea - is known as artha (अर्थ, pronounced uh-r-thuh), literally “object”, “referent”, or “meaning.”

The artha by itself is the object “as it is”, without a curtain of thought.

Generally, when seeing an object, the artha stands in isolation for a brief moment, before the barrage of word and idea come barreling down, obscuring the object from view, and placing it into categories.

Try to imagine a time that you stood in front of a beautiful view, and felt your breath taken away. Then, remember how at some point, the mind began to wander, as the beauty lost its grip on your attention.

Attention wanders only when the curtain of thought becomes the predominant factor in perception.

The practice of samaadhi helps us to view the artha by itself, in isolation from this curtain of thought, thus helping us to see the world more clearly, without placing our images onto it.

Two types of perception

In normal perception, word, meaning, and idea follow each other so quickly that we mix them up, and act as if they were one thing.

This “mixing” is called sankeerna (संकीर्ण, literally “confusion”), and the mental whirlpool we use to do this mixing is a vikalpa, or imagination. Specifically, the three are not actually the same thing, but we imagine them to be.

This type of regular perception - where word, meaning, and idea are undifferentiated - is known as loka-pratyaksha (literally “world perception” or “mundane perception”) or aparapratyaksha (or “the lower perception”).

In loka-pratyaksha, the object is veiled from view, as the mind rushes to categorise it into a generic class.

We see something, and say “cow” - now we are thinking about the image of a “cow” in the mind, rather than the cow in front of us.

As an example, we often do this in relationships with other people. We watch them carefully just long enough to place them into a category - good, bad, Hindu, Muslim, atheist, Sagittarius, take your pick - and then treat them through existing patterns of behaviour.

As a result, we miss the outliers - the things that they might be which do not fall cleanly into the categories we have created. In fact, we may even do this with ourselves, creating a self-image that limits our own actions in the world.

What’s more, when we do this, we start to live in a world of these mental images - words and ideas - rather than in the world in front of us, which is vibrant and full of variation. This world of mental images is dull, lifeless, and boring - it feels like we have already seen it, and that there is nothing new.

This results in feelings of being jaded, disillusioned, and dejected.

What we may not notice is that the reason it feels dull, lifeless, and boring, is that it is made up of our own mental constructions. Of course there is nothing new - after all, we constructed it to begin with. Of course it is empty, it does not have any substance!

Through the practice of vitarka samaadhi, we can start to create patterns of seeing the external world as it is - vibrant and ever-fresh. We can start to live in a world of specifics rather than a world of generics. Here, every object, even if they might have looked identical to begin with, is completely new. In this way, one can start to see the world through the eyes of an innocent baby.

This kind of fresh-eyed perception is known as “parapratyaksha”, or the higher perception.

Now that we have understood the distinction between word, meaning, and idea, and the effects that this curtain of thought has on our everyday perceptions, next week, we will discuss how this distinction applies to the first level of Samaadhi.

Until then:

Try to notice the distinction between word, meaning, and idea in your day to day life. See what happens when you come across something where you don’t have a word for it - does the mind rush to name it?

Continue your practice of Dhaaranaa. When the final bell rings, see if you can keep your mind entirely on the aalambanaa for three full breaths, and only get up once you have managed to do so.

Next time: Vitark Samaadhi: Savitark and Nirvitark Samapatti

There are schools within Indian philosophy which hold that meaning is inherent in words - some that it is inherent in particular words, and others that it is inherent in words in general. This imperceptible meaning-bearing part of a word is known as a sphota.