What is your ground?

The 5 Bhumis: States of Mind

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Welcome back! Over the last few weeks we have gone over the 25 Tattvas, or the 25 categories of the Universe that form the metaphysical foundation of the Sankhya and Yoga philosophies, and last week, we discussed Purusha, or You, the Pure Consciousness.

At this point we will start to dive into practical applications to our day to days lives based on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali - one of the foundational texts of Yoga - and traditional commentaries by Vyasa, Shankaracharya, and several others.

For some context, the Yoga Sutras are not the “source” of Yoga, but rather a compilation of existing practices. In Indian philosophy, unlike in the West, not much importance is given to the source, since, in truth, there are no original ideas, only combinations of existing teachings (in fact, ancient teachers would often attribute their works to their own teachers in a sort of reverse plagiarism). Patanjali, who most likely lived around 500 BCE, acknowledges this in his first Sutra where he uses the prefix “anu” to indicate that these teachings existed long before him.

अथ योगानुशासनम् |Atha YogaanushasanamNow, the continued teachings on Yoga

Yoga Sutras 1.1

At this point, Vyasa, in his commentary, begins a discussion on the 5 Bhumis. The word “Bhumi” (pronounced bhoo-mi, where bh is pronounced as in the made up word cab-hut), means “ground.” These 5 states are a framework to help us understand the ground upon which our mind settles, and from which our mental activities grow.

Our minds change from moment to moment, but at any given time in our lives there is a tendency for the mind to come back “home” to one state over others. This ground where the mind comes to rest is the Bhumi.

Your Bhumi may change over the course of a lifetime, and this is the intention of Yoga - to progress the Bhumi from one to the next.

It is helpful to know your current Bhumi so that you can put a stake in the ground (no pun intended) with regard to your mind, and see the change over time as you deepen your Yogic practice. As with all frameworks, don’t take it too seriously - just use it as a tool to know your mind better.

According to Vyasa, there are 5 Bhumis:

Kshipta: Wandering, Agitated

Mudha: Confused, Dull

Vikshipta: Scattered

Ekaagra: One-pointed

Niruddha: Controlled, Mastered

These are in order of progression towards the highest state of Yoga, represented by the final stage, Niruddha. Another way to phrase this is that they are ordered by the degree of Sattva in comparison to the other gunas. As we go through each one, try and notice your own mind and see if you can figure out which Bhumi you are currently in, at this point in your life. Ask the question “what state is my mind usually in”, and be unflinchingly honest with yourself. If you find it difficult to figure it out immediately, write down the state of your mind a few times a day, and look back at your notes after a week or two to see if any patterns emerge - what shows up the most?

Kshipta: The Agitated, Wandering Mind

Kshipta is when the mind is constantly agitated. This is characterised by feelings of anger, violence, passion, self-centeredness, and restlessness. If you find yourself angry a lot of the time, or if you notice that a lot of your thoughts are “me” focused, this is likely your current Bhumi. This state is extremely unstable and can easily be thrown into tidal waves of movement with the slightest provocation. An example of someone with a kshipta mind is a person who gets angry or violent when they perceive a threat to their sense of self (physical or psychological).

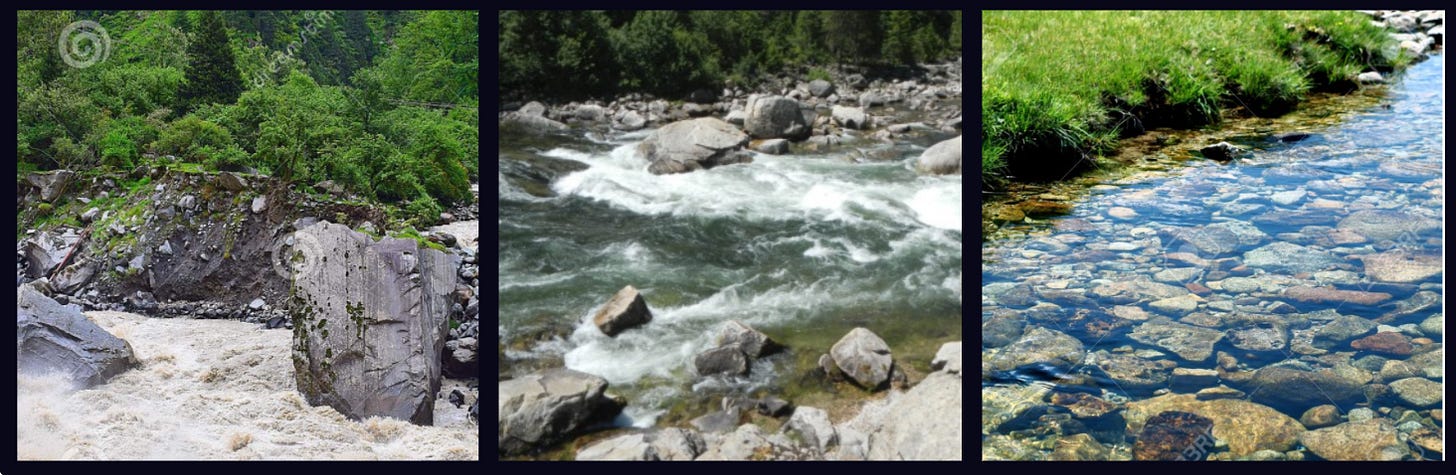

You might notice that these characteristics are similar to the characteristics of Rajas and Tamas. This is because the Kshipta is highly Rajasic and Tamasic in nature, with minimal Sattva. The Kshipta mind is like a raging and muddy river, destroying everything in its path.

Mudha: The Dull, Confused Mind

Mudha (pronounced moo-rha, sort of) is a mind which is highly inertial. It is characterised by feelings of anxiety, delusion, and depression. The mind in this state is constantly ruminating and not acting. One may feel as though there is a dark cloud covering the mind, where moving through life feels like moving through thick oil. If you feel constantly demotivated, have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning, regularly experience feelings of worthlessness or meaninglessness, accompanied by a background sense of malaise, this is your current Bhumi.

Notice, this Bhumi is highly Tamasic, with minimal Rajas and Sattva. The Mudha mind is like a slow, sticky, muddy river, barely moving and covered in algae.

Vikshipta: The Scattered Mind

Vikshipta is the state which most people experience. It is the everyday mind - focused sometimes, but mostly scattered. One might feel occasional bouts of focus or “flow” when working without distraction for a period of time, during meditation, or when reading or listening to elevating material, but fall back into distraction afterwards.

If you ever notice that you are in a state of focus or flow, that is an indication that Vikshipta is your Bhumi, since it means you are comparing this state to a time when you are not focused.

This Bhumi has more Sattva than the previous two, but is still influenced by Rajas and Tamas.

Ekaagra: The One-Pointed Mind

Ekaagra (pronounced ache-aah-gruh) literally means “one-point” (Eka, or one + Agra, or point). This is the mind of a Yogi who has achieved the first of the seven Samadhis, or states of meditative absorption. A person with an ekaagra mind is able to achieve a flow state at will, with any object of their choosing, and is not easily prone to unwanted distraction. The ekaagra mind is calm, clear, lucid, and joyful on account of minimal vrittis (more on this later).

This Bhumi has an extremely high degree of Sattva, with minimal Rajas and Tamas.

Niruddha: The Mastered Mind

Niruddha means a state of mastery or total control, as a good charioteer has total mastery over their horses. It is not a control of force, but rather a control of skill. Reflections of this type of control can be experienced even in Asana (ie. postural Yoga) practice, but in this context it is applied to the mind. This Bhumi is the pinnacle of Yogic practice, and is featured in Patanjali’s definition of Yoga:

योगश्र्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः|YogaschittavrittinirodhaYoga is the mastery of the vrittis in the chitta (ie. Yoga is the mastery of the movements in the mind)

- Yoga Sutras 1.2

A mind in this state has no vrittis whatsoever. It is the mind of a Yogi who has attained the seventh and highest meditative absorption - asamprajnata or objectless Samadhi. Traditional commentators compare it to a fire in which seeds, once burned, never again sprout.

In this state of mind, the inner Bliss shines through completely. The Yogi experiences an expansive awareness, and the complete cessation of all suffering, characterized by the dissolution of the boundary between what voluntary and involuntary actions feel like. The mind in this Bhumi - like in the Ekaagra Bhumi above - has a maximal degree of Sattva, with minimal Rajasic and Tamasic influence.

However, what’s new here is that the Self (ie. Purusha, in this context) is no longer identified with the Gunas at all. In this stage the “Yogi” has disappeared (so to speak) by way of transcending the gunas altogether. There is a Realisation1 that there never was any world, any birth, death, person, or Gunas to begin with. This last part may sound esoteric, but will become more clear later in this series when we start to discuss Advaita Vedanta.

To recap, there are 5 Bhumis - grounds or states of mind:

Kshipta: Wandering, Agitated

Mudha: Confused, Dull

Vikshipta: Scattered

Ekaagra: One-pointed

Niruddha: Controlled, Mastered

All mental states are momentary, but at any given point in one’s life, the mind falls back into one of these “default” states. The order in which they are presented above represents a progression towards the ultimate goal of Yoga - a mind that is completely mastered, or Niruddha.

Ok, this is cool and all, but how do I actually use this framework in a practical sense?

This framework can be used in three ways (and perhaps more) - knowing what practices might work for you better than others, evaluating your own progress through your Yoga journey, and making a habit of objectifying the mind rather than identifying with it.

If you find that your mind is defaulting to kshipta, calm it down. If you find your mind defaulting to mudha, focus on increasing activity. If vikshipta is your Bhumi, focus the mind, and once it is focused (ekaagra), work to master it completely. The goal is to move from the one you are at to the next one on the list.

Knowing your Bhumi is the first step to knowing which practices are right for you. To make this clearer, let us take the example of seated meditation (which itself is a broad category within one of the many practices within Yoga).

For someone in the Kshipta Bhumi, the restlessness of the mind makes it very difficult to sit still, and so seated meditation will be an uphill battle. For folks in this Bhumi, selfless service or Eka Tattva Abhyaas (the practice of focusing on one thing at a time) may be a more useful practice to calm the mind and reduce the Rajasic tendencies.

For someone who is currently Mudha, seated meditation may exacerbate issues that are already present - for example, depressive or suicidal thoughts will become more clear, but without the clarity of Sattva that might help them “watch” the thoughts come and go, the person may end up in a deeper and more visceral depression than that with which they started. For people in this category, Patanjali’s Kriya Yoga (not to be confused with the practices taught by Paramahansa Yogananda under the same name) is perhaps a more fruitful place to start.

On the other hand, Kriya Yoga (for example), while certainly helpful for any Bhumi, may not have the effectiveness of the mastering the mind for someone in the Ekaagra category that some seated meditation practices may have.

Having said this, everyone’s mind is different. You know the inner workings of your own mind better than anyone else, and so it is best to experiment and see what works for you. As you practice, you can use this framework to notice and evaluate your progress.

In addition to knowing where to start in terms of practice, and being able to evaluate your progress, regularly noticing your Bhumi as it changes throughout your journey creates a habit of objectifying the mind rather than identifying with it. This practice of objectification of the mind is in itself a way to increase the Sattva in the mind.

Until next week, use this framework to notice the state of your mind. Write it down a few times a day, and notice the patterns that emerge. Like with any journey, knowing where you are is the first step to getting anywhere.

Next time: The 5 Vrittis: Mental “whirlpools”

You may notice capital letters on some words, e.g. Self, Realisation, You, Reality, Consciousness, etc. It is not random! The capital letters denote Brahman, the Ultimate Reality. The specific meaning of this will become more clear as we delve further into the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta in future articles, once the stage has been set with the more practical practices of Raja Yoga.