I want to do it, but I can't bring myself to do it: Part I

Increasing willpower through Kriya Yoga: Tapas and Svaadhyaay

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Often, we want something in our minds, but we are unable to translate it into action. For example, you may want to wake up early in the morning and meditate, but when the alarm goes off, the warmth of the bed is too alluring to let go of, and you hit the snooze button.

Another example, you may decide you want to lose or gain weight. You read about various diets and exercise regimens, but when it comes time to actually put those ideas into action, you may start out strong, only to give in to your desire for your favourite food or relaxation as time passes.

There are countless such examples, but the essential point is summed up beautifully in a verse from the Pandava Gita, where Duryodhana (the apparent villain) justifies his actions to Krishna:

दुर्योधन उवाच ।जानामि धर्मं न च मे प्रवृत्तिजानामि अधर्मं न च मे निवृत्तिः ।केनापि देवेन हृदि स्थितेनयथा नियुक्तोऽस्मि तथा करोमि ॥ ५७॥I know what is right, but I can’t bring myself to do it.

I know what is wrong, but I can’t stop myself from doing it.

It’s as if there is some [malicious] power situated in my heart,

Whatever it tells me to do, I do.

- Duryodhana, Pandava Gita, 57

We often have an idea in the mind, and we have a desire to follow it, but somehow, something pulls us in the opposite direction. We want to wake up and exercise, but somehow when the time comes we convince ourselves that it’s ok to sleep in a little longer. We want to abstain from unhealthy food, but when it’s in front of us, we convince ourselves that “just this time” it’s ok. Even procrastination is a result of the same phenomenon - we want to do some work now, but we convince ourselves that we’ll get to it later.

In Yoga psychology, this tendency of the mind is the result of the kleshas. Particularly, the buddhi may have the will to do a particular action (e.g. diet, exercise, meditation, anything at all), but if the kleshas are strong (ie. udaar or vichhinna) they overpower this will, and the result is that we follow our old habit patterns.

So far in this series, we have gone over the basics of how Yoga works - we want to get rid of old tendencies and create new ones, and the method is through vairaagya (letting go) of old tendencies and abhyaas (practice) of the new tendencies. However, this is much easier said than done. We may want to practice, but our kleshas get the better of us.

To bring this home, consider your own experience in reading the previous articles. You may have considered bringing yourself to practice the techniques at the bottom of each article, but if you look back and evaluate, depending on the intensity of the kleshas in your mind, you may have tried it a bit and let it go, or postponed it until later, even though you thought it was a good idea.

In the analogy of the field in the articles on abhyaas and vairaagya, we discussed how the field of the mind is naturally tilted towards the direction of the objects of the external world. Fascination with these objects is what limits our so-called “will-power”, and easily distracts us from Yoga, just as a child is easily distracted by an iPad.

P: Ok, cool, I get it. I want to do these things, I know they will help me feel happier, calmer, and more fulfilled, but I can’t bring myself to do them. I procrastinate all the time, and do all sorts of mental gymnastics that block me from doing what I want to do. What should I actually do? Is there a practice that will help me increase my willpower?

Jogi: Yes, there is. It is called Kriya Yoga, or the Yoga of action.

Kriya Yoga: The Yoga of Action

तपःस्वाध्यायेश्वरप्रणिधानानि क्रियायोगः॥TapahSvaadhyaayIshvarPranidhaanaani kriyaaYogahSelf-discipline, Self-study, and Surrender to Ishvara [taken together are called] Kriya Yoga.

- Yoga Sutras, 2.1

Kriya Yoga (not to be confused with the Kriya Yoga of Paramahamsa Yogananda) is intended for the Yunjamaana - the Yogi who wants to practice Yoga and is just getting started. This person understands the value of the practice, wants to get into it, but can’t really bring themselves to do it. However, the benefit of Kriya Yoga is not limited to those who want to practice Yoga - it is for anyone who wants to train their mind to do their bidding.

Adi Shankaracharya famously states:

किंकरस्य किंकरैः अहः किंकरी कृतो ॥Kinkarasya kinkaraih ahah kinkari kritoAlas, I have become the servant of my servant’s servants.

- Adi Shankaracharya

Your servant is the mind, and the mind’s servants are the senses. However, in this funny state of affairs, we have found ourselves to be subservient to not just our mind, but our senses as well.

In order to understand Kriya Yoga, let us recap the analogy of the chariot.

आत्मानं रथितं विद्धि शरीरं रथमेव तु । बुद्धिं तु सारथिं विद्धि मनः प्रग्रहमेव च ॥इन्द्रियाणि हयानाहुर्विषयां स्तेषु गोचरान् । आत्मेन्द्रियमनोयुक्तं भोक्तेत्याहुर्मनीषिणः ॥Aatmaanam rathitam viddhi shareeram rathamEva tuBuddhim tu saaratim viddhi manah pragrahamEva chaIndriyaani hayaanAahurVishayaam steshu gocharaanAatmaIndriyaManoYuktam BhoktaItiAhurManeeshinahKnow the Self as the lord of the chariot, the body as the chariot itself, the Buddhi as the charioteer, and the Manas as the reigns.

The senses, they say, are the horses, and the objects are the path. The Self, the senses, the mind taken together, are called the “Enjoyer” (aka bhoktaa) by the intelligent ones.

- Katha Upanishad, 1.3.3-4

The body is the chariot, and each sense is a horse. The mind (specifically manas) is the reins, and the intellect (ie. buddhi) is the charioteer. You, the Purusha, are the rider in the chariot, watching everything happen.

If the horses are uncontrolled, no matter where the charioteer wants to go, the horses will not follow.

If the horses want to stay still, even if the charioteer wants them to move, they will stay still. On the other hand, if the horses want to move, even if the charioteer wants them to stop, they will keep moving.

The horses are a lot stronger than the charioteer, and so at the end of the day, the charioteer can’t do much unless the horses agree. This is like when you want to wake up at 6 am and meditate or work out, the alarm goes off, but you hit the snooze button rather than getting out of bed. The horses always win.

On the other hand, if the charioteer is skilled, and the horses are trained, the moment the charioteer gives the command, the horses will do their bidding. Even if the charioteer commands the horses to wade through a river, a swamp, or a fire, the horses will follow.

So now the question is, how should we train the horses, and build up the skill and strength of the charioteer? How do we train the senses, and build up the skill and strength of the buddhi? The method is threefold:

Tapas: Self-discipline

Svaadhyaay: Self-study

Ishvarpranidhaan: Self-surrender

Through this practice, there are two results:

समाधिभावनार्थः क्लेशतनूकरणार्थश्र्च ॥SamaadhiBhaavanaArthah KleshaTanooKaranaArthashCha[Kriya Yoga is] for the purpose of cultivating Samadhi, by way of attenuating the kleshas.

- Yoga Sutras, 2.2

The kleshas get weaker: Specifically, the kleshas are reduced to the tanu, or attenuated state. This leads to stronger willpower - the ability for the buddhi to control body, mind, and senses. By practising Kriya Yoga, what your buddhi decides, your body and senses will do.

Samaadhi is unlocked: The final limb of Yoga is Samaadhi, or meditative absorption. This is not something that you can do, but rather something that happens to you. However, we can create a fertile ground for Samaadhi to happen by weakening the kleshas, through the practice of Kriya Yoga.

In this week’s article, we will go over the first two disciplines in Kriya Yoga - tapas and svaadhyaay - and next time we will go over the third: Ishvarpranidhaan.

Tapas: Self-discipline

Tapas (pronounced tuh-pus) literally means “fire” or “heat” and is often translated as “austerities” or “purificatory action.” The essential practice is to cultivate and strengthen the willpower by carefully noticing what it feels like to act from the buddhi rather than by following tendencies, and then cultivating and strengthening that feeling.

The technical definition of the buddhi is nishchayaatmika antahkaranavritti or “that movement of the mind which decides/determines.” For the purposes of this article, it is referred to as the nischaya-vritti (“the deciding mental whirlpool”). It is not a part of the mind, but rather a subtle movement within it. This is not theoretical - we can experience this right now.

Let’s try a quick exercise so we know what this means:

Close your eyes.

Touch the tip of your nose with your hand.

Notice, the instructions did not specify which hand to use. Your buddhi decided that. This decision appeared in the form of an extremely subtle movement in your mind - this subtle movement in the mind which decided which hand to use is the nishchaya-vritti.

Let’s try another exercise, but this time, notice the nischaya-vritti closely:

Close your eyes.

Touch the tip of your nose with any finger of your choice.

There may have been some rumination at first when you went back and forth between options (this is the manas), but the final decision to pick whichever finger you picked was the nishchaya-vritti. This nischaya-vritti is your charioteer - get to know it well.

In the exercises above, the activation energy required to do the action was very low - touching your nose may be an easy task. However, when it comes to doing something more difficult, the nishchaya-vritti is easily overcome by other movements in the mind driven by the kleshas (e.g. desire, aversion, fear). For example, you want to exercise in the morning, but you are attracted (raag) to the warmth of your bed (pramaan), and averse (dvesha) to the idea (vikalp) of exercise.

With tapas, we systematically strengthen this nishchaya-vritti by:

Noticing what it feels like, and then

Intentionally cultivating that feeling in the mind.

Over time, all your actions can be driven by the buddhi rather than by existing tendencies. When this happens, you are able to direct your chariot where you want to go, rather than where the horses want to take you.

The method of tapas is to pick an action that you find difficult or uncomfortable, and practice it regularly.

Now there is a delicate balance here. On one hand, the action you choose for your tapas cannot be so difficult that it throws the mind into disarray, or that you develop an aversion towards it. On the other hand, if it is too easy, the nishchaya-vritti will not be strong enough for you to notice. This balance is different for each person.

Some examples of tapas are fasting, taking a cold shower, sleeping on the floor, exercising at a particular time every day, waking up to your alarm without snoozing, not speaking for a particular period of time during the day, or anything that you consider to be difficult given your own mental tendencies. Just pick one thing, and use it as a tool to notice and cultivate the nischaya-vritti.

Even within these, there are degrees of tapas. For example, if you choose to fast, you can fast at particular times, or on a particular day of the month (or the week, or even the lunar cycle - up to you really). Additionally, you can choose to not eat or drink anything at all, drink only water, drink water and eat only particular foods (e.g. fruit, nuts, only vegetarian food, etc.). While there are many supernatural claims to the type and timing of a fast, from the perspective of Yoga fundamentals, it doesn’t really matter.

The main thing is to practice deciding to act, and then acting according to the decision.

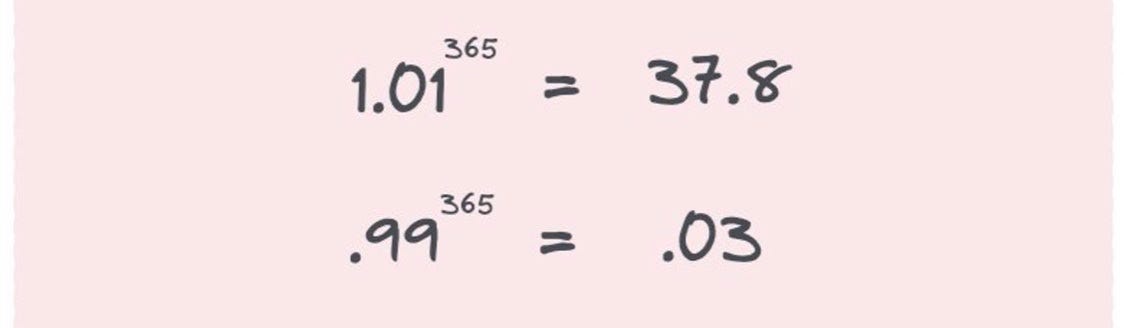

Keeping up this practice using the 4 keys to practice (ie. for an extended period of time, without a break, with internal honesty, and paying close attention) will help to increase your propensity to act from the buddhi rather than based on the kleshas.

From the perspective of the gunas, tapas increases Sattva, and clears or reduces Rajas and Tamas.

In fact, the importance of tapas is such that Vyasa, in his commentary on the Yoga Sutras states:

नातपस्विनो योगः सिध्यति |NaAtapasvino yogah sidhyatiWithout tapas, Yoga cannot be established.

- Vyasa’s commentary on Yoga Sutra 2.1

Over time, as your tapas gets easier to do, increase the intensity so that it is still challenging for you. You can liken this to lifting weights at the gym. Start with a weight that is not so heavy that you can’t lift it, or that it injures you, but not so easy that you don’t get any gains. Over time, increase the weight to build your strength.

Something important to note - do not use regular meditation as your tapas. The reason is that any tapas runs the risk of creating an aversion in the mind, and generating an aversion towards meditation is counterproductive to the goals of Yoga. Additionally, make sure not to do any tapas that harms the body in any way. The first of the nine obstacles to Yoga is vyaadhi, or bodily disease. If your tapas harms the body, it is counterproductive to the goals of Yoga.

Svaadhyaay: Self-study

स्वाध्यायाद्योगमासीत योगास्वाध्यायमासते |SvaadhyaayaadYogamAaseet yogaaSvaadhyaayamAasateFrom Svaadhyaay comes Yoga, and from Yoga comes Svaadhyaay.

- Vyasa’s commentary on Yoga Sutra 1.29

Svaadhyaay (pronounced svaah-dh-yaahy, where the dh is pronounced as in the beginning of the word “though”) literally translates to Self-study. Specifically, it refers to a daily study of any Moksha Shastras, or soteriological material - that is, any books, talks, articles, videos, podcasts, etc. relating to Moksha, or liberation. This can be the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, the Bible, the Qur’an, the Torah, the Guru Granth Sahib, the Yoga Sutras and its commentaries, Meister Eckhart, Adi Shankaracharya, Eckhart Tolle, Alan Watts, Ram Dass, or literally anything that deals with this subject matter, from any tradition of the world (Yoga is non-sectarian).

Some examples from the Indic traditions that do not qualify as svaadhyaay are the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Puranas, the Manusmriti, the Karma-Kanda in the Vedas, or any other books of stories or treatises on so-called “ethical action” or ceremonies.

Often, within the texts of the world’s religious traditions, there is a mix of ethics, stories, and revelation. For example, the Bible includes a number of stories, rules, but also Jesus’ teachings (e.g. the Sermon on the Mount). Svaadhyaay is specifically the study of these revelations and their esoteric teachings (called Shruti, as opposed to Smriti).

The method of Svaadhyaay is threefold, in this order:

Shravana: Listening, such that you can at least repeat what has been said without mistakes

Manana: Doubting and reasoning until all doubts are dispelled with satisfying answers

Nididhyaasana: Assimilating the teachings until they are real to you

The regular study of this material increases two main faculties:

Vivek: This is the ability to discriminate between the Real and the unreal, and starts with the ability to closely distinguish the meanings of the teachings as an ant can carefully sift sugar from a mixture of dirt and sugar. This skill helps to clearly sift interfering thoughts and ruminations (e.g. “I can sleep in a few minutes longer” or “I can make it up tomorrow”) from the deciding thought (“I am going to wake up and exercise” or “I will do this right now”).

Vairaagya: The ability to let go, specifically here letting go of the identification with the mind-body complex. Normally our strong identification with the body pulls us in the direction of what is easy or comfortable. Weakening this identification allows us to let go of interfering thoughts in favor of deciding thoughts (aka the nishchaya-vritti).

Through svaadhyaay comes the weakening of avidya, which is the root of all kleshas, and the fundamental cause of our (apparent) bondage to samsara.

Finally, the regular practice of svaadhyaay ensures that you know more today than you knew yesterday.

This knowledge, while ultimately a part of Maya, enables the Yogi to cross the river of samsara to the opposite shore of Moksha. If this last sentence sounds a bit esoteric, don’t worry, it will become more clear as we dive more into Jnana Yoga in future articles.

To summarise, Kriya Yoga has three components:

Tapas: Self-discipline

Svaadhyaay: Self-study

Ishvarpranidhaan: Self-surrender

We went over the first two - Tapas, and Svaadhyaay - and will go over the third, Ishvarpranidhaan, next week.

For this week’s exercise, we will turn the intensity up a notch. Without actually putting Kriya Yoga into action, the following articles will remain mere theory. The idea is to build up your willpower so that what you read, you can actually do.

However, remember to be kind to yourself. If something is not within your capacity, go for something easier. Tune the practice to your own abilities - no one knows your mind better than you.

Until next time:

Tapas: Write down your tapas - writing it down is a method to keep yourself honest, since you will be less likely to change it at the last minute before practicing. Make sure that it is difficult enough to notice the nishchaya-vritti, but not so difficult that it creates a pattern of aversion or harms the body. Practice your tapas regularly, without giving in to the tendency towards comfort.

Svaadhyaay: Every day, read or listen to any soteriological material of your choice. It can be from any of the world’s great traditions. If you have any questions about this, or if you want more specific guidance, feel free to reach out by responding to this email or leaving a comment below.

Keep track of your practice in your journal, and notice if the kleshas in your mind are weakening over time.

Next time: Ishvarpranidhaan: Self-surrender

Quick App recommendation (iOS only though): As a person who has had a REALLY difficult time carrying out intentions, creating new habits, and tracking them, I found that the "Done" app is the best (simplest) way to track my Kriya Yoga practice. Just sharing what helped me in case it may help someone else!

(https://apps.apple.com/us/app/done-a-simple-habit-tracker/id1103961876)

Hello Kunal ji! Where I can begin my soteriological study? Please suggest.