I want to do it, but I can't bring myself to do it: Part II

Increasing willpower through Kriya Yoga: Ishvarpranidhaan

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Once, a horse suddenly came galloping down the village road. It seemed as though the man seated on it had somewhere important to go.

A bystander, standing along the side of the road, saw this and shouted, “where are you going in such a hurry?”

The man responded, “I don’t know! Ask the horse!”

Last week, we began a discussion on Kriya Yoga, or the Yoga of action. This is a preliminary method for Yogis who are just getting started, and a way of life for more advanced practitioners. The purpose of Kriya Yoga is to increase willpower, by way of reducing the kleshas to the tanu (weak/attenuated) state, thus cultivating the ground for Samaadhi (the final limb of Yoga).

As with the horse in this story from the Zen tradition, the mind and the senses often get the better of us - we may want to wake up and work out, stop procrastinating, abstain from unhealthy foods, or meditate regularly, but the mind is clever, and somehow manages to convince us not to act in accordance with our will. Where our mind and senses take us, we follow, as though powerless.

Last time, we looked at a quote from the Pandava Gita where Duryodhan, the apparent villain, tries to justify his actions to Krishna. A similar quote is also found in the Bhagavad Gita, where Arjuna asks Krishna a question about the same subject matter:

अर्जुन उवाच | अथ केन प्रयुक्तोऽयं पापं चरति पूरुष: | अनिच्छन्नपि वार्ष्णेय बलादिव नियोजित: ||Atha kena prayuto’Ayam paapam charati purushahAnichhannApi Vaarshneya balaadIva niyojitahWhat is that by which a person is made to commit bad deeds, O Krishna, as though pulled by some force against their will?

- Bhagavad Gita, 3.36

This is exactly the feeling that we all have. We want to do one thing, but some force pulls us in the opposite direction.

In Yoga Psychology, it is the 5 kleshas that, when they are strong, prevent us from acting according to our own will. The method for increasing willpower, therefore, is to weaken the kleshas, and this method is called Kriya Yoga.

The method is threefold:

Tapas: Self-discipline

Svaadhyaay: Self-study

Ishvarpranidhaan: Self-surrender

Last week, we discussed the first two - tapas and svaadhyaay. This week, we will go over the third and final part of the Kriya Yoga - Ishvarpranidhaan, or Self-surrender. This is one of the most powerful practices in all of Yoga, and is sufficient for liberation in itself. Even if it is practised just a little bit, it can lead to a significant reduction in feelings of anxiety, sadness, anger, and fear.

In the context of Kriya Yoga, Svaadhyaay and Ishvarpranidhaan balance out the effect of Tapas. Without these two, Tapas can lead to a stronger identification with the buddhi - the decider - which is counterproductive to the goals of Yoga. Svaadhyaay gives us the wisdom to understand the “why” behind the practices, and Ishvarpranidhaan helps us weaken the identification with the mind-body complex (ie. the root of all suffering) which is what Yoga is ultimately all about.

Ishvarpranidhaan: Self-surrender

The word Ishvarpranidhaan (pronounced eesh-vuhr-pruh-nih-dhaan) literally means to “Place under Ishvar.” But what is Ishvar?

Ishvar is most often translated as the personal God, but for those of us who doubt or question the existence of God, this may feel like a difficult jump to make.

If you are theistically inclined, great. In this case, Ishvarpranidhaan is simply a surrender of the fruits of your actions at the feet of your personal God, with gratitude to God for your current situation, and a knowledge that everything you would normally consider to belong to you, is actually just borrowed from God.

Whatever tradition you come from, and whatever your conception of God, the three fundamentals of the practice are:

Gratitude: Thanking God for everything that you have - big and small.

Sacrifice: Acknowledgment of the fact that everything that is “yours” is actually God’s, and you are just borrowing it.

Surrender: Surrendering the fruits of your actions to God.

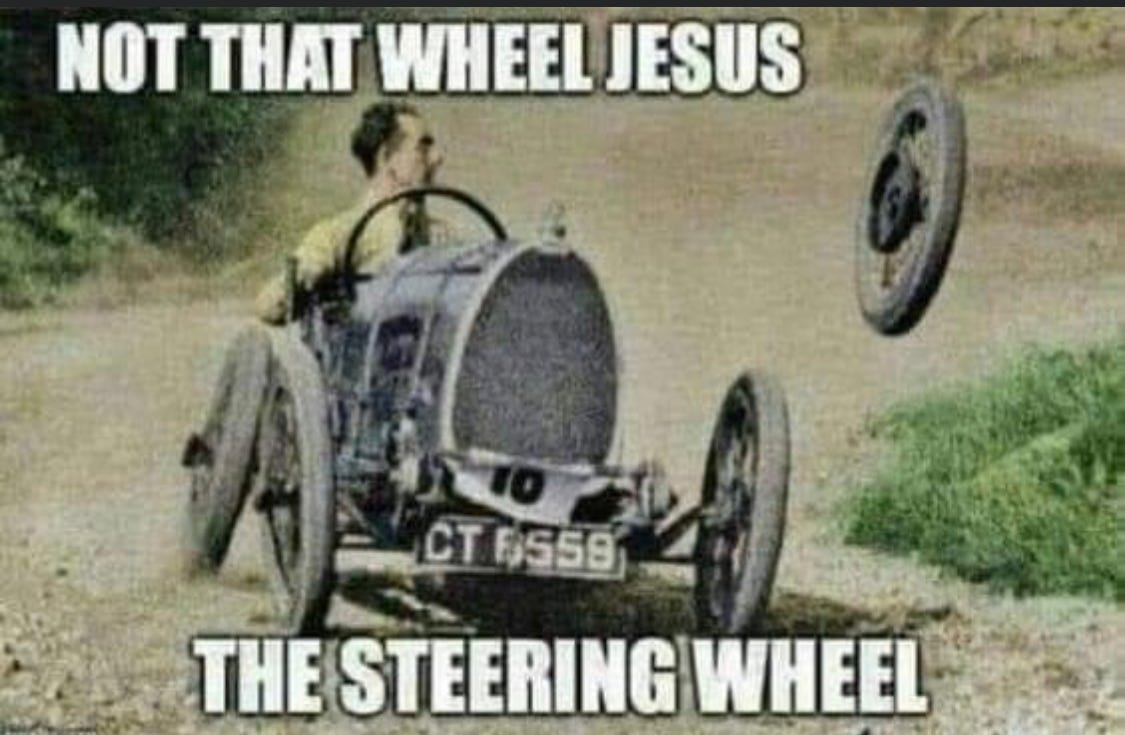

While the first two may be fairly obvious, there is a four-step method of surrender that will be discussed in more detail later in this article. In a nutshell, a beautiful phrase that describes this practice is to “let Jesus take the wheel.”

Considering yourself to be the doer of your actions is as silly as a child with a toy steering wheel, sitting in the passenger seat of the car, acting like they are driving. Know that God is the doer of all your actions - this is surrender.

To quote Ramana Maharishi, “He knows what is best and when and how to do it. Leave everything entirely to Him. His is the burden: you have no longer any cares. All your cares are His. Such is surrender.”

Now if you are not theistically inclined, the paragraphs above may have made you feel somewhat uncomfortable. Don’t worry, you can keep reading. In Yoga and Vedanta, God is not something to be simply believed in, but to be doubted, questioned, understood through reason, and then known through direct experience. For the purposes of Kriya Yoga, however, a belief or understanding of God is not actually necessary. Yoga is an exercise in seeking truth, not an exercise in faith.

At this stage, there are two approaches for this category of atheist or agnostic Yogis:

The Jnani1 approach: Practicing Ishvarpranidhaan after gaining a logical understanding of God.

The atheist approach: To practice Ishvarpranidhaan without God.

The Jnani approach: Practicing after gaining a logical understanding of God

In Yoga and Vedanta, God is not some mythical bearded being sitting in a heavenly throne amongst the clouds judging everyone for their actions - rather, It is a metaphysical reality with a clear definition.

We will go over “God” in logical terms in more detail in a future article, and, as mentioned above, for the purposes of Kriya Yoga, a belief in God is not necessary. Briefly, however, Ishvar (aka the personal God) is defined as Mayopahitachaitanyam, or “Pure Consciousness with the limiting adjunct of Maya.”

There are several ways to understand what Maya is, but I will mention two here:

Desha, Kaala, Nimitta: Space, time, and causation

Miyate Anaya Iti Maya: That by which we measure (the collective avidya)

But what does the term “limiting adjunct” mean?

To understand this, consider a clear crystal placed near a coloured piece of cloth. When the crystal is close to the cloth, it seems to take on its colour. In this situation, the limiting adjunct is the colour of the cloth.

Now consider the jiva - the individual sentient being, or what you normally consider yourself to be - a combination of mind, body, and awareness. The jiva is Pure Consciousness with the limiting adjunct of the individual mind and body. Pure Consciousness (aka the Purusha) seems to take on the qualities of the body and mind, just as the clear crystal seems to take on the colour of the cloth.

In the same way, when Pure Consciousness has the limiting adjunct of Maya, it is called Ishvar.

Alternatively, one can understand Ishvar as the collective of the deep sleep state.2 As a forest is the collective of trees, a murmuration is the collective of flying birds, or a lake is the collective of drops of water, Ishvar is the collective3 of the individual deep sleep blankness. As the individual experience of the waking and dream worlds emerge from the deep sleep state at the individual level, what we refer to as “the Universe” appears from the collective. This is how “God creates the Universe.”

This is a shift in how we normally understand reality. Normally, we think we exist within an already existent Universe. Here, the Universe (aka waking and dream worlds) exist in seed form in the deep sleep state from where they emerge, and into which they merge again.

Once again, God is not something to be simply believed in, but to be known and experienced directly. Once you understand God in this way, in terms of reason, the same steps apply: gratitude, sacrifice, and surrender.

If this is all too much to think about, don’t worry, there is still a method to practice Ishvarpranidhaan without any conception of God whatsoever.

The atheist method: Practicing Ishvarpranidhaan without God

If you don’t want any conception of God - based on either faith or reason, there is still a way to practice Ishvarpranidhaan. The three principles remain the same, but with a slightly different method for each:

Gratitude: Giving thanks to the circumstances which brought you to where you are right now, including the entire breadth and depth of causal factors, with an attitude of wonder for how the entire Universe, since the beginning of time, has conspired to make your situation possible.

Sacrifice: Realising the fundamental truth of impermanence. You cannot hold on to anything, and trying to hold on is a major cause of our suffering. Sacrifice here means to let go of the false idea of permanence, and to recognise the impermanence of your possessions, your situation, your relationships, your body, and your mind.

Surrender: Realising that you are not the actor, and that it is just your ahamkaar taking credit for the workings of nature. This can be done by noticing the infinite depth and breadth of causal factors that led to the outcomes you normally give yourself credit or blame for.

For this third piece of “surrender”, consider the phrase “It is raining.” Who is the “it” that rains? There is, in fact, no “doer” of the rain - it is just happening. However, due to the rules of grammar, we feel that we must add a subject to the sentence.

Similarly, consider the phrase “lightning flashes.” There is no “lightning” that is doing the “flashing” - lightning is happening, but we felt the grammatical urge to split it into a subject and a verb.

Now we can apply this same logic to ourselves. You might normally think “I am reading”, but this third step of Ishvarpranidhaan means to reframe this thought as “reading is happening.” Rather than saying “I am walking”, reframe it to “walking is happening” or rather than “I am breathing”, reframe it to “breathing is happening.” This constant reframing eventually leads to a dis-identification with the false “I” - the root of all suffering.

Surrender: The third piece of Ishvarpranidhaan

In the traditional commentaries, a famous verse from the Bhagavad Gita is often quoted. This is applicable whether you are a theist, an atheist, a Jnani, or agnostic, and regardless of which of the world’s religious traditions you identify with.

कर्मण्येवाधिकारस्ते मा फलेषु कदाचन |मा कर्मफलहेतुर्भूर्मा ते सङ्गोऽस्त्वकर्मणि ||KarmaniEvaAdhikaarasTe ma phaleshu kadaachanaMa karmaPhala heturBhoorMa te sango’AstuAkarmaniYou have the right only to your actions, never to the fruits.

You are not the cause of your actions. Do not be attached to inaction.

- Bhagavad Gita, 2.47

This is a four-step systematic breakdown of the “surrender” aspect mentioned above. This is the method:

Act without attachment for the results of your actions

Surrender the fruits of your actions (ie. not thinking of the fruits of the actions as “mine”)

Give up the pride of doership (ie. giving up the false idea that “I am the doer”)

Don’t not act

Ok, this sounds great, but why does this work?

First, on acting without attachment to the results. If you are attached to the results of your actions, there is a great deal of anxiety present in the mind during the action. This worry about the results is a distraction from the action itself. Normally, when we focus on doing something, we try our best to let go of any distractions, whether physical or mental. Funnily enough, though, we let in one particular type of distracting thought, because we somehow deem it to be relevant - thoughts about the results of our actions. Now in reality, there are many causal factors that will determine the results of your actions, and your actions are only one node in an infinite web of causes and effects. As a result, if we were to allow thoughts about the results as we are acting, we will be in a constant state of anxiety, leading the mind to be less focused, and more stressed. If we have one eye on the result, we only have one eye left on the action.

To quote Alan Watts, “No amount of anxiety makes any difference to anything that is going to happen.”

Second, on surrendering the fruits of our actions. Thinking of ourselves as the enjoyer (bhoktaa) of the fruits of our actions leads to a strengthening of the already strong identification with the mind, body, and senses. As we have seen, You are not the mind-body complex, and thinking that you are is the root cause of your suffering. In terms of kleshas, thinking of the fruits of your actions as “mine” leads to a strengthening of avidya and asmita. In terms of karma, this chain of action and result is the very definition of karma, and the entire project of Yoga is to break free of it. In this way, thinking ourselves as the enjoyer of the fruits of our actions is counterproductive to the goals of Yoga.

Third, on giving up the pride of doer-ship. Saying, or even thinking, that “I did it” is quite simply false. Nature acts, and “you” are just the thought that appears in the mind when it comes time to take credit. Consider walking - do you know how to walk? You may say, “yes, of course”, but if you had full conscious control of all your muscles, sinews, tendons, and nerves, walking would be an impossibly complex task. You don’t know how to walk, but yet you take credit. In the same way, saying that “you did it” is a false statement that strengthens the identification with the mind-body complex, leading to further suffering.

P: If I’m not concerned about the results of my actions, and if I’m not considering myself as the doer of the actions, why should I act at all? I’m motivated by the results, and by how others will view me - if I’m giving all that up, I may as well just chill and do nothing, no?

Jogi: Chilling and doing nothing is also an action. No individual can escape action. Additionally, doing nothing in this way is still due to an attachment to the result (ie. relaxation, chilling) that you consider “mine.”

Given that this tendency may arise from the first three, continue to act as you normally would. The shift is only a mental one. Act based on your best knowledge of cause and effect, but give up attachment or thirsting for the results. If and when the fruits arise, realise that they are not yours, although you may witness their enjoyment, and give up the false idea that you are the sole cause.

Act in such a way that whether or not you succeed, it makes no difference to You, the Purusha - the witness of the action and its results. If the results are good, many factors were at play, and if they are bad, many factors were at play. Just like the example of the mango tree, this body-mind is just one in an infinite set of causal factors, and You are unattached witness of them all, as a mirror is unattached to the images that appear in it.

This is summed up in the immediate next verse in the Bhagavad Gita:

योगस्थ: कुरु कर्माणि सङ्गं त्यक्त्वा धनञ्जय |सिद्ध्यसिद्ध्यो: समो भूत्वा समत्वं योग उच्यते ||YogasthaKuruKarmaani Sangam Tyaktvaa DhananjyayaSiddhiAsiddhyoh Samo Bhootvaa Samatvam Yoga UchyateBeing steadfast in Yoga, perform your actions, having given up attachment [to the results]. Be even in success and failure - this evenness is Yoga.

- Bhagavad Gita, 2.48

To summarise, Kriya Yoga has three practices:

Tapas: Self-discipline

Svaadhyaay: Self-study

Ishvarpranidhaan: Self-surrender

Ishvarpranidhaan itself is a threefold method that can be practiced with or without any conception of God:

Gratitude

Sacrifice

Surrender

Finally, within surrender, the method is fourfold:

Act without attachment for the results of your actions

Surrender the fruits of your actions (ie. not thinking of the fruits of the actions as “mine”)

Give up the pride of doership (ie. giving up the idea that “I am the doer”)

Don’t not act

Until next time: Practice Kriya Yoga, specifically

Tapas: Continue your tapas. Make sure that it is difficult enough to notice the nishchaya-vritti, but not so difficult that it creates a pattern of aversion or harms the body. Practice your tapas regularly, without giving in to the tendency towards comfort.

Svaadyaay: Every day, continue to read or listen to any soteriological material of your choice.

Ishvarpranidhaan: Every day, mentally list 5 things you are grateful for - they can be big or small, complex or simple. Build a habit of noticing the impermanence of everything around you, including yourself. Additionally, as you act, focus on the action rather than the results, surrendering the results and the pride of doership.

Keep track of which ones you did each day, and notice if the kleshas in your mind are weakening through the practice.

Next time: Avidya: How we lie to ourselves

Jnani (pronounced gyaa-nee or nyaa-nee) means “knower”, and is derived from the word Jnana (pronounced gyaan or nyaan) which means “knowledge.” In this context it refers to a Yogi who is drawn to the path of Jnana Yoga - the Yoga of Knowledge (ie. the path to freedom through philosophy).

The collective of dreamers is known as Hiranyagarbha (ie. the Golden Womb), the collective of the waker is known as Viraat, and the collective of the deep sleep state is known as Ishvar (the personal God). These definitions are from the Mandukya Upanishad. Only this third aspect of Ishvar is relevant in Patanjali’s Raja Yoga. Additionally, Patanjali has a number of other verses on Ishvar, where It is referred to as “the specific/special Purusha untouched by kleshas and karma”, “the teacher of the ancients”, “undivided by time”, and is known by the name of “Om.”

Technically speaking, the “collective” of the deep sleep state is identical with the individual deep sleep state. More on this later.