How we lie to ourselves: Part I

The Four Confusions: Impermanence and Uncleanliness

Note: If you are new to this newsletter, you may find that additional context is needed to fully grasp what’s going on. Don’t worry. The words highlighted in green are links to previous articles that are relevant to the present post. If you’d prefer to go in chronological order, you can find the first article here.

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

दुःखं एव सर्वं विवेकिनः|Dukkham eva sarvam vivekinahTo the intelligent one (ie. the one with vivek), everything is suffering.

- Yoga Sutras, 2.15

The Yogi, it is said, is as sensitive as an eyeball. If a small piece of dirt falls on the hand, the leg, or any other part of the body, it is no matter, but if it falls on the eyeball, the discomfort cannot be ignored.

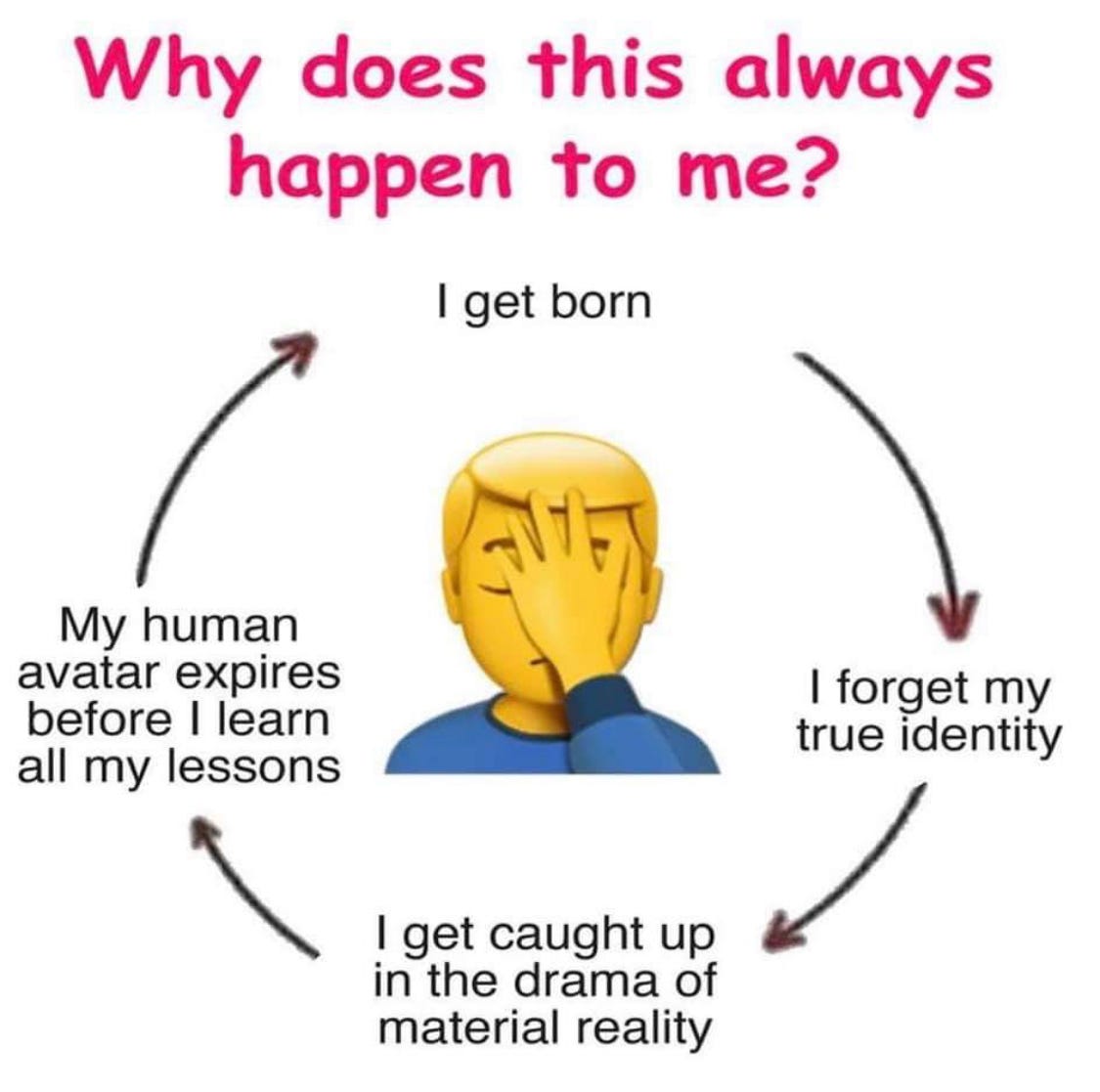

We live our lives simply running towards pleasure and away from pain, always unfulfilled, until the body runs out, and then - if reincarnation is a part of your worldview - it’s the same story all over again, in an infinite cycle of death after death after death.

मृत्योः स मृत्युं गच्छति य इह नानेव पश्यति ॥Mrityoh sa mrityum gachhati ya ih naaneva pashyatiWhosever sees any differentiation here (ie. does not Realise the Truth) goes from death to death.

- Katha Upanishad, 2.1.11

While most people either don’t notice this cycle of suffering, or try to hide from it, the Yogi sees it clearly, and feels it deeply. They see that what most people call “pleasure” is in fact shrouded in suffering, like honey mixed with poison, and want a way out. This is where Yoga really begins.

Thus far in this series we have discussed methods to feel calmer, increase our willpower, as well as some Yoga psychology to better understand what’s going on in the tangled web of our minds.

However, the root of the problem is not a muddy or turbulent mind.

Sure, we suffer less when the mind is calm and clear, and for many, this may be sufficient. However, while a clear mind is helpful (and necessary for Yoga), it does not solve the root of the problem - the primal ignorance, called avidya.

What is Avidya?

Avidya (pronounced uh-vid-yaah) means ignorance, but it isn’t just any old ignorance. Normally, ignorance is a negative entity (ie. an absence of knowledge) - you don’t know something, so you solve your ignorance by learning. This type of ignorance, however, is a positive entity (bhaava-roopam), and rather than solving it with some new knowledge, it needs to be removed, just as a sculptor removes stone to reveal the form of the sculpture.

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.”

- Michelangelo

Avidya is the root of all the kleshas, and is likened to a field from which all the other kleshas emerge. If you remove avidya, all the kleshas disappear along with it. In Yoga and Vedanta (as well as in several other Indic philosophical traditions), it is the fundamental root of all suffering, and the removal of avidya is called Moksha, or freedom.

While there are many definitions of avidya, it is defined by Patanjali as follows:

अनित्याशुचिदुःखानात्मसु नित्यशुचिसुखात्मख्यातिरविद्या |AnityaAshuchiDukkhaAnaatmasu NityaShuchiSukhAatma KhyaatirAvidyaaConfusing the impermanent as permanent, the impure as pure, suffering as pleasure, and the non-self as self is Avidya.

- Yoga Sutras, 2.5

In summary, avidya manifests itself as a combination of four confusions:

Confusing the impermanent to be permanent

Confusing the unclean to be clean

Confusing suffering to be pleasure

Confusing non-self to be Self

These confusions are not always on the surface. Most often, they are hidden deep within the recesses of the mind, making avidya far more difficult to root out than the other kleshas. These four confusions are like walls that we spend our entire lives building up, so that we don’t have to face the truth directly, allowing us to ignore what’s really going on like an ostrich with its head in the sand1. Looking at it in this way, rather than translating avidya as “ignorance”, translating it as “ignore-ance” may be closer to the meaning.

We consider these walls important to protect ourselves from suffering, but in fact, they are the very cause of our suffering. These walls are a product of avidya, and it is no easy task to break them down. From the perspective of the gunas, these walls are tamas in action.

This week, we will discuss the first two confusions. Next week, we will pick up with the next two, as well as an overview of the solution - the eight-limbed (ashta-anga) Yoga.

Confusion #1: Confusing the impermanent to be permanent

Consider a time that you lost something or someone you loved. Remember the suffering that it caused.

Perhaps you lost a cherished keepsake, a memory, or even a job. If you notice closely, you will see that it is your expectation of permanence that is the cause of your suffering, not the loss itself.

It is similar with people. While it may be difficult to easily admit, one of the reasons we grieve the death of loved ones is that somewhere deep in the back of our minds, we had felt that the person would be with us forever, and now they are gone. We expected permanence, perhaps at a subtle level, but the truth of impermanence smacked us right in the face. What’s more, in order to avoid the truth of impermanence, we go so far as to convince ourselves that we will see them again, inventing ideas about heaven, the afterlife, reincarnation, and perhaps even the stars.

“Wilting flowers do not cause suffering. It is the unrealistic desire that flowers not wilt that causes suffering.”

- Thich Nhat Hanh

This confusion of permanence and impermanence also extends to ourselves. We crave for the permanence of our body, our mind, our work, our identities, and our experiences. Then, when we notice that they are changing or disintegrating, we suffer. We try to fix up our physical appearance with medicine, make-up, clothing, and sometimes even surgery. We try to repeat positive experiences again and again, suffering to extend them as long as we can so as to keep up the illusion of permanence. When it comes to the mind, we suffer when we lose memories that we cherish, trying to remind ourselves with photographs, retelling of stories, and holding on to souvenirs.

But just hiding from the truth of impermanence isn’t enough for us. We go so far as to try to construct an illusion of permanence for our own comfort, and then live as though it is true. We often get the most frustrated with the people that we love, treating them as though they will always be around. When it comes to ourselves, we act as though we will live forever, constantly postponing the things we want to do because we assume that there will be another time to do them.

This is summed up beautifully in a story from the Mahabharat where Yudishtir, one of the main characters (and Arjuna’s eldest brother), is asked to describe the most astonishing thing about humans. He says,

अहन्यहनि भूतानि गच्छन्तीह यमालयम् |शेषाः स्थावरमिच्छन्ति किमाश्चर्यमतः परम् ॥ahaniAhani bhootaani gachchhantiIha YamaAlayamSheshaah sthaavaramIchhanti kimAascharyaMatah paramEvery moment, armies of creatures march into the house of the Death. [Despite knowing this, humans] consider themselves to be immortal. What can be more astonishing than this?

- Mahabharat, Vana Parva 313.116

What’s more, we expect permanence in others, and when we don’t see it, it exacerbates our confusion. We try to categorise people into boxes of identity, passing judgements and treating them as though they are static. We say things like “that’s so you”, “I think you will like this” or even “I wouldn’t have expected that from you”, putting our expectations of permanence on full display. To take this a step further, we apply this to ourselves, trying to keep up with the (very real) benefits of a permanent image by creating personal brands, curating our social media accounts and resumes, and then taking these symbols of ourselves seriously.

We go through tremendous suffering in search of permanence through money, power, achievements, and success, hoping in the back of our minds that it will make us feel stable, and therefore, happy and fulfilled. We want houses that we can call our own, where we can raise our families, and which we can pass down for generations. We want to create legacies so that if not our bodies or minds, at least our names will live on forever.2

But the truth is that it will all change, and eventually fade away. Even the most solid rocks turn to dust. Everything, absolutely everything is impermanent, and we suffer because we don’t face it.

अनित्यं अनित्यं सर्वं अनित्यं |Anityam anityam Sarvam anityamImpermanent, impermanent, everything is impermanent.

- Gautama Buddha

Confusion #2: Confusing the unclean to be clean

There are two types of shuchih - cleanliness - as we will discuss in a future article dealing with the Niyamas, the second limb of Yoga. They are:

External cleanliness: This is the physical cleanliness of the body and its surroundings.

Internal cleanliness: A mind devoid of selfishness, and thus devoid of feelings of jealousy, anger, hatred, and delusion.

This confusion extends to both - let us go over each one.

External cleanliness

As an example of this confusion in the aspect of external cleanliness, consider the feeling of lust. The traditional example describes the following scene:

नवेव शशाङ्कलेखा कमनीयेवं कन्या मध्वमृतावयवनिर्मितेव चन्द्रं भित्वा निःसृतेव ज्ञायते | नीलोत्पलपात्रायताक्षोहावगर्भाभ्यां लोचनाभ्यां जीवलोकमाश्र्वासयन्तीवेति कस्य केनाभिसंबन्धः |Naveva Shashaankalekhaa kamaneeyevam kanaa madhvamritaavayavanirmiteva chandram bhitvaa nihsriteva gyaayate. Neelotpalapaatraayataakshohaavagarbhaabhyaam lochanaabhyaam jeevalokamamaashvaasayanteeveti kasya kenaabhisambandhahThe girl is attractive like the new moon. Her limbs are, as it were, made of one and nectar. She looks as though she has emerged from the moon. Her eyes are large like the leaves of a blue lotus. With playful flashes of her eyes, she imparts life to this world.

- Vyasa Bhashyam on Yoga Sutra 2.5

Now while this traditional example is specifically about the (somewhat puritan, no pun intended) lustful thoughts about a woman, this extends to any sort of lust for any sort of body. The body is constantly deteriorating, excreting all kinds of juices and waste from the pores and all the other orifices. It needs to be constantly cleaned. And yet, somehow, in the heat of passion, we sort of “forget” about all this, and consider the body to be pure.

Note: This is not saying that lust is bad, or that these thoughts are somehow “unholy.” Lust is simply an indication that there is an underlying confusion in the mind. There is no value-judgement involved, just a noticing of the facts.

The Buddha makes this very clear in a visualisation he suggests for his students in the Maha Sattipatthana Suttanta (the foundational text for vipassana):

“And again, bhikkus, a bhikku examines and reflects closely upon this very body, from the soles of the feet up and from the tips of the head-hair down, enclosed by the skin and full of various kinds of impurities, thinking thus, “There exists in this body: hair on the head, hair of the body, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, membranes, spleen, intestines, feces, brain, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, solid fat, tears, liquid fat, saliva, mucus, lubricating oil of the joints, and urine.””

We try to make our body look clean and pure with nice clothes, perfumes, make-up, and jewellery, in an effort to hide from the fact of the matter, which is that the body is just a bag of skin with flesh and bones, filled with potentially embarrassing substances, and that is slowly deteriorating.

Note: To be clear, this is not a suggestion to be ashamed of one’s body. Love your body as it is, but notice it for what it is.

This confusion even extends to the food we eat! For those of us who eat meat, this is the easiest to see - we hide from the truth of where it came from - a decaying corpse of an animal that was most likely raised in the midst of disease and death. If someone even suggests this truth in the middle of a meal, the walls become clearly visible as anger, frustration, or disgust. What’s more, we try to continue hiding by saying things like, “don’t say that!” or “why are you ruining my meal?”

However, it doesn’t end there. Even plants came from places where there was dirt, feces, and all kinds of microbial life that we would normally find disgusting, but in order to experience the pleasure of a well-cooked meal, we put up a wall of avidya to hide from the truth.

Note: There is no compulsion to be vegetarian, vegan, or to stop enjoying ourselves. This is simply a matter of noticing the facts for what they are, and carefully examining the mechanisms we use to hide from the truth.

Internal Cleanliness

When something isn’t going the way we want it to, our immediate tendency is to blame others. You got into a fight with someone, but in your mind it’s their fault, not yours. It is always the other person that is annoying, selfish, jealous, impractical, narrow-minded, immature, or any number of other things.

S.N. Goenka (often credited with bringing vipassana to the West) gives the example of a household:

“When all importance is given to things outside, then one always remains under the delusion that I am miserable because of things outside.

“I am miserable because so and so said this or so and so did this. All the cause of my misery I will keep feeling is outside, outside, outside.

A husband will say “If my wife changes a little, our house will become like a heaven, everything will be alright. She has to change a little.” And ask the wife, she says, “my husband has to change a little - little change in my husband oh, wonderful!”

“The father will say the son should change a little. The son will say the father should change a little.

“The mother-in-law will say the son-in-low should change, the daughter-in-law should change. And the son-in-law or daughter-in-law will say the mother-in-law should change.

“Everyone else should change, not I. I am perfectly alright. What’s wrong in me?

“Because you find fault only outside, outside. You always find the cause of your misery outside.”

Your own mind is just as “unclean” as everyone and everything else, but you consider it to be “clean.” Somewhere in the back of your mind, you are perfect, and everyone and everything else is the cause of all your problems. This ignoring of your own effect on the outcomes in your life is an example of how avidya manifests in this particular confusion.

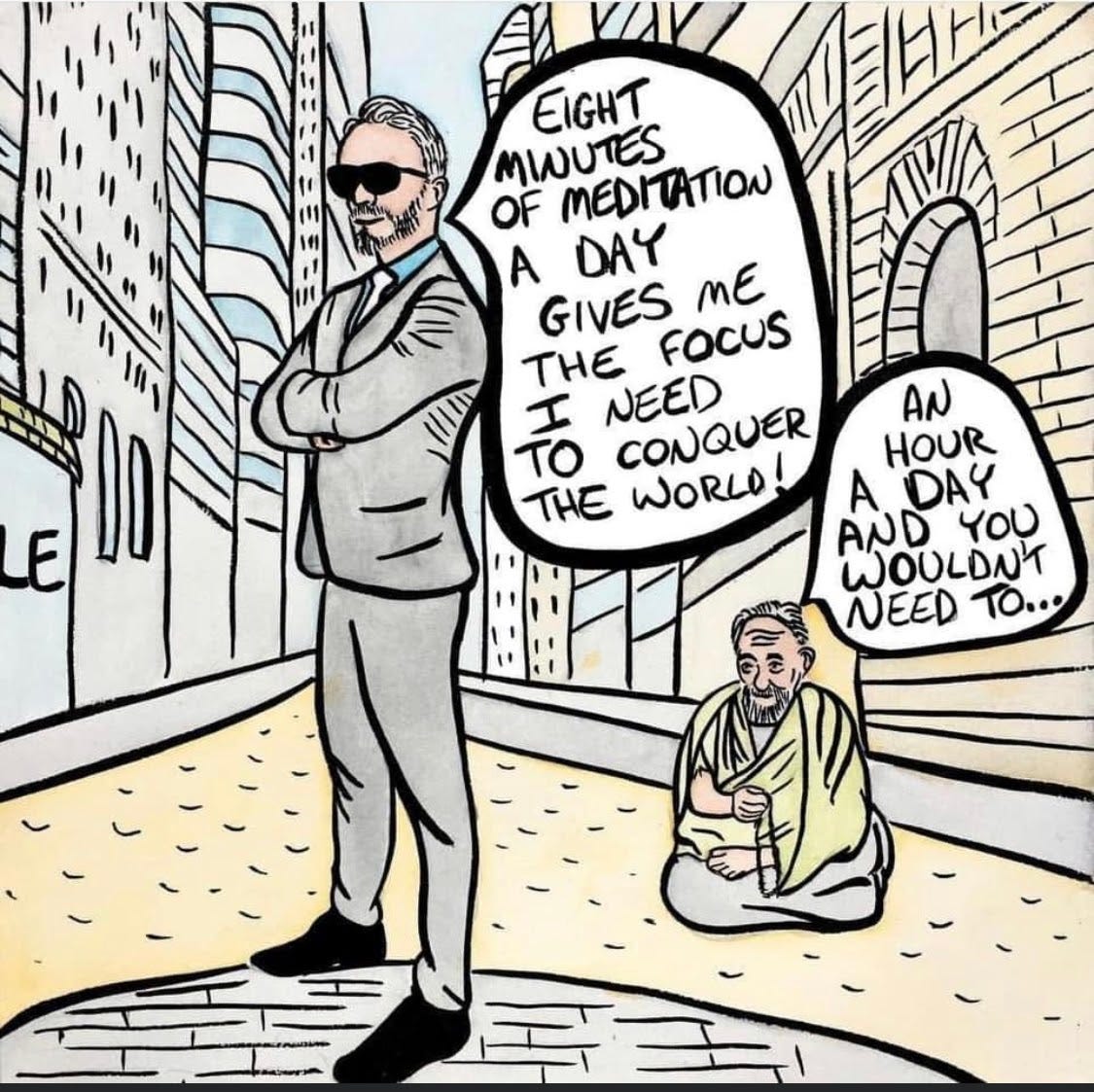

To take this a step further, consider your motives in learning about Yoga, in practicing meditation, or, if you are theistically inclined, your motives in believing in God. Why do you engage in “spiritual” practice? Is your motive “clean”?

Jogi: Why do you engage in “spiritual” practice? Are your motives “clean”?

P: What do you mean “clean”?

Jogi: Devoid of selfishness.

P: Yes, of course.

Jogi: Ok, then why are you here?

P: I want a calmer mind.

Jogi: Is that not selfish? It will make you more effective, happier, and more fulfilled - isn’t that just for you?

P: No, it’s because that will make me a better person. In fact, it will make me less selfish.

Jogi: Well, why do you want to be a better person? Why do you want to be unselfish?

P: So that I can do good in the world - so I can selflessly serve others, and help them out of suffering.

Jogi: Ok, why do you want that?

P: So that other people can be happy - it’s not about me. My motives are pure.

Jogi: Why do you want others to be happy?

P: I just do - it’s fundamental.

Jogi: Is it? Does making others happy make you happy?

P: (pauses) - yes. I suppose it does.

Jogi: So you wanting to be unselfish has a selfish motive?

This is our current predicament. Our motives are ultimately selfish, no matter how selfless they may seem on the surface. They are “unclean”, but in our ignorance (avidya) we consider them to be “clean”, and like with the other confusions, we tend to ignore it, out of a fear of facing it head on.

Finally, there is a deeper meaning to this confusion of cleanliness and uncleanliness. The mind is like a muddy, turbulent river. The movements of the water are like vrittis (e.g. perceptions, memories, imaginations, etc.), and the mud is like the kleshas (attraction, aversion, fear, etc.). As we have discussed at length, You are the witness of the movements of your mind, not the mind itself. This is likened to sunlight illuminating a puddle of water.

Now if the sunlight hits a dirty puddle, it doesn’t get dirty. Similarly, when You witness the mind, even in its turbulence, You are unaffected. The mental phenomena come and go, but You remain still - witnessing all that arises and falls. However, in our confusion, we think that we are affected by what we witness. We feel as though the “clean” Purusha is somehow “dirtied” by the kleshas and vrittis in the mind, when actually what is affected is also nothing but mental phenomena. This mental phenomena is also witnessed by You, the Purusha.

To make this clear, imagine that you notice anger in your mind. Anger arises, and you think “I am angry.” You feel like this anger has affected you in some way, when actually, the anger has perhaps changed your rate of breathing, increased your heart rate, and created a state of mental turbulence. Your rate of breathing, the heart rate, and even the mental turbulence are all phenomena that are witnessed by You, but soon they will pass, and You will remain unaffected.

P: I won’t be unaffected. I’ll remember that I was angry - my memory is affected, no?

Jogi: Who witnesses the memory?

Memory is also a mental phenomena that is witnessed by You, the Purusha. Ultimately, anything that you can point to as “affected” or “dirtied” by the “unclean” mental phenomena is also an object perceived by You, who are completely untouched.

Wait a second. Why do we care about these confusions?

Ultimately, the goal of Yoga is far beyond a healthy body and a calm mind. While these are great side-effects, what’s on offer is much more - the complete cessation of all suffering.

The first step is to acknowledge the avidya in our own lives. This is a lot harder than it sounds. The truth of these confusions can be a hard pill to swallow, and for many, just considering them can result in agitation, dejection, or even anger.

The highest reaches of Yoga are not for the faint of heart - it takes courage to face these truths as they are. If you are not ready, this is no problem - there is no compulsion to notice these, and certainly no need to proselytize. To each in their own time, and to each their own path.

Once these truths have been acknowledged, however, the Yogi can notice how these confusions result in suffering in their own life. This only comes once the mind is somewhat calm, and inclined to turn inward, and so Yoga begins with preliminary practices to calm the mind and increase the will-power.

It is only at this point that the ultimate solution is seen as the removal of avidya. After all, why should we worry about weakening the individual kleshas when we can get rid of them all in one fell swoop?

Until next time:

Continue to strengthen your practice of Kriya Yoga. This will come in handy once we start to explore the eight-limbed Yoga in detail, if you are interested in putting these ideas into action.

As you go through the week, consider the impermanence of the things around you. This extends not only to physical objects like your body, your house, your phone, or your clothes, but also to mental objects like your memories, your identities, and your ideas. In what situations are you hiding from the truth?

Additionally, consider where you are hiding from the truth of “uncleanliness” both at the physical (external) and mental (internal) level.

Take notes on the reactions in your mind when you bump into these truths throughout the day - this will help to show you how these walls of avidya manifest in your own mind.

Next time: The Four Confusions: Part II

As it turns out, this is a popular misconception about ostriches that originated in Ancient Rome. The actual reason ostriches stick their heads in the sand is to occasionally rotate their eggs, which are buried in their underground nests (since they can’t fly).

This is also true at the level of national identity. We find nationalist governments the world over mythologizing the past, creating a “stable” image of what it means to be Indian, American, Turkish, etc. This generates suffering in the minds of millions who notice the ever-changing country before them and fall into trap of the very natural desire for permanence. This intentionally generated suffering is then used as a tool to garner support for particular political parties or individuals, creating divisions in society and thus perpetuating suffering.