"You" are just nature.

Prakriti and the Three Gunas

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Welcome back! For the past two weeks, we have been going over the 25 Tattvas, or the 25 categories of the Universe from the Sankhya philosophy, which underlies Yoga. We have now covered the entire antahakarana or internal instrument (the “mind”), as well as the “external” world. So far, we have discussed:

The 5 Mahabhutas: Physical/Gross Elements

The 5 Tanmaatras: Subtle Elements

The 5 Buddhendriyas: Organs of Perception

The 5 Karmendriyas: Organs of Action

Manas: Lower Mind

Ahamkaar: The “I”-maker

Buddhi: Intellect

Today, we will discuss Prakriti and the 3 Gunas, and next time, we will go over Purusha, or the individual Pure Consciousness. These are the final two categories in this framework.

According to Sankhya and Yoga, in this Universe there are really only two fundamental, eternal categories - Purusha and Prakriti. They exist eternally together. In mythology, they are symbolized by Shiva and Shakti - Shiva is the unmoving, unchanging, blissful Pure Consciousness, and Shakti is the divine feminine - the creative power that manifests as this material Universe.

Prakriti (pronounced pruh-kri-tee) is not just the stuff outside the boundary of our skin, but includes our bodies, minds, and even thoughts, perceptions, imaginations, feelings, motives, decisions, and even our sense of self. Anything that is not the Pure Experiencer is Prakriti. Anything which you can call “this” is Prakriti.

Normally, this is not where we draw the line between ourselves and nature, and so we live in a state of confusion. Sometimes my thoughts are me, sometimes they are separate from me. Sometimes my body is me, other times it is an object in my experience. For example, one might say “I’m in pain” and “My foot hurts” to describe the same experience, or use the phrases “my body” and “me” interchangeably to describe the same object. This part of the framework helps us to remove this confusion by clarifying where “I” stops and “nature” begins.

Nature is composed of three threads

“Prakriti” (pronounced pruh-kri-tee) literally means “nature.” All objects are nothing but Prakriti in different configurations.

Normally, when we say the word “object”, we think of something outside the boundary of the skin. Here, an object is anything to which you can say “this” (e.g. this body, this mind, this thought, this decision).

If you think about it, we humans have grown out of nature in much the same way as an apple grows out of an apple tree or a wave grows out of water. But somehow, due to our lifelong conditioning, we have grown to feel like this bag of blood and bones is a separate entity from the world around it. In truth, all of this - all objects - are nothing but nature, dancing blissfully. It is also nature that takes it all so seriously, and it is nature that wants a way out.

The word “guna” literally means “quality” or “attribute”, but, Sanskrit being polysemic, it can also mean “thread”, or specifically a thread in a cord of twine.

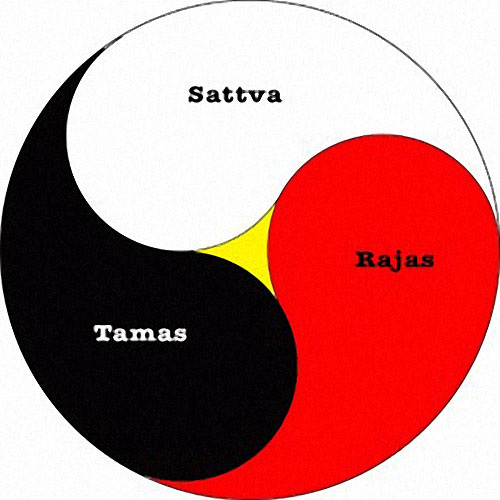

The idea here is that all of nature - everything that we experience, including the world, our bodies, minds, and even our thoughts - is composed of three basic building blocks, or three threads. These three threads are called Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas.

The three gunas are always in combination with each other - one can never appear independently of the other two. The only thing that differentiates objects from one another is the ratio of Sattva to Rajas to Tamas.

This ratio is what ultimately determines the quality of an object - for example, your body has more tamas than a thought, and a thought has more sattva than your body. This ratio also determines the quality of the mind - a dull mind is more tamasic, a scattered mind is more rajasic, and a clear mind is more sattvic.

Prakriti is eternally in motion, constantly changing. These changes start when the three gunas are out of balance with each other. Rajas provides the force for movement, Sattva provides the creativity and harmony, and Tamas checks, or slows down the process. When they are in equilibrium, there is no movement. Time is nothing but movement, and so it can be said that Prakriti has been in motion since the beginning of time - Prakriti is, quite literally, eternal.

The practices in Yoga are to maximize sattva in proportion to the other two gunas, to prepare the Yogi to eventually transcend the three gunas altogether. This may sound like something “spooky” or “spiritual” but really, it is something in our everyday experience - no faith needed. In each of the examples below, note the quality that is common to all of the objects with a preponderance of a particular guna. To make it even more clear, you can also notice the effect that the examples have on your mind, in your direct experience (e.g. eating a heavy meal will make you feel more tamasic than eating a salad).

To define the gunas we will use an ostensive definition - which is where we can use a list of things to which a term applies in order to grasp its meaning intuitively.

Sattva

Sattva is the guna of lucidity, clarity, harmony, balance, illumination, creativity, peace, virtue, calmness, and elevation. It is a revealing and luminous quality. Following are some comparisons that might help clarify the term ostensively:

A thought has more sattva than your hand.

Air has more sattva than a rock.

A salad has more sattva than fried chicken.

Compassion has more sattva than anger.

Sound has more sattva than smell.

Speaking has more sattva than excreting.

If you look at the diagram of the 25 Tattvas at the top of this article, the higher up you go, the higher the sattva in proportion to the other two gunas.

We know we have a high proportion of sattva when we feel calm and clear, creative, happy, peaceful, and compassionate towards others regardless of circumstance. When the mind feels sharp, or in a state of flow, it is because sattva is predominant.

In Yoga, the goal is to maximize the amount of sattva through practices in day to day life, as well as through seated meditation. Knowing this framework helps to understand the “why” behind Yogic methods.

In the example of the raging, muddy river, the clear, turbulent river, and the calm clear river, the calm clear river has the most sattva. However, sattva is always there, it is just a matter of uncovering the rajas and tamas to let it shine.

Rajas

Rajas (pronounced ruh-juhs) is the guna of passion, activity, movement, dynamism, and individualism. Here are some comparisons to help clarify it:

Running has more rajas than standing.

Wind has more rajas than still air.

Motivation has more rajas than lethargy.

Coffee is more rajasic than water.

Spicy food is more rajasic than a plain salad.

Speaking fast has more rajas than speaking slow.

Melody has more rajas than monotony.

In the diagram of the 25 Tattvas, the Karmendriyas (organs of action) are more Rajasic than the Mahabhutas (physical elements).

Having more rajas is good for when you need to act, move, or have passion. For example, an athlete might want to be more rajasic before an event, a performer might want more rajas before a performance, or an executive might want more rajas before a presentation.

Too much rajas, however, can lead to frustration, greed, hyperactivity, pushiness, or aggression. People with a lot of rajas are usually found with extensive to-do lists, constantly needing to move on to the next thing, insatiable desires, and often have difficulty sitting still or sleeping. You know you are running on Rajas when you feel tired (Tamas) afterwards, or when it is hard to “turn it off.”

Have you ever acted a certain way, knowing that you shouldn’t have, only to regret it later? Have you ever said done anything regretful even though you knew better?

In the Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna asks Krishna this very question:

अथ केन प्रयुक्तोऽयं पापं चरति पूरुष: | अनिच्छन्नपि वार्ष्णेय बलादिव नियोजित: ||Atha kena prayukto’yam paapam charati poorushahAnichhan api vaarshneya balaadiva niyojitahImpelled by what, as though dragged on, does a person commit sinful acts,

As though constrained by some force against his will?

- Bhagavad Gita 3.36

To this, Krishna replies:

काम एष क्रोध एष रजोगुणसमुद्भव: | महाशनो महापाप्मा विद्ध्येनमिह वैरिणम् ||Kaama esha krodha esha rajo-guna-samudhbhavahMahaashano mahaapaapmaa viddhyenam iha vairinamIt is the Rajas Guna which leads to desire, and then anger. Know this (Rajas) as The Great Sinner, The Great Devourer, the enemy in this material world.

- Bhagavad Gita 3.37

When we want to sit still and meditate, but we can’t, or we want to be less angry, but some mysterious force keeps us from actually being more peaceful, it is Rajas that is the driver of these actions.

Tamas

Tamas (pronounced tuh-muhs) literally means “darkness.” It is the guna in dullness, inertia, sloth, negativity, delusion, apathy, inactivity, violence, and fear. Some comparisons to help ostensively define it are:

The body has more tamas than a thought.

A rock has more tamas than air.

A heavy, buttery meal has more tamas than a salad.

Sadness has more tamas than joy.

Apathy has more tamas than equanimity.

Sleep has more tamas than waking.

Destruction has more tamas than creation.

Alcohol has more tamas than water.

Monotony has more tamas than melody.

If you have ever had the experience of snoozing your morning alarm multiple times because you are too groggy to wake up, this is tamas in action. When you feel tired after a heavy meal, or after you’ve had a lot to drink, it is because of the influence of tamas. If you feel apathy about the world, and have turned off the news to intentionally ignore it, this is tamas. If you want to meditate but just can’t bring yourself to do it, it is because of too much tamas. If you act without thinking about the consequences, this is tamas obscuring your intellect.

Tamas isn’t all bad, though. Without it, we would not be able to sleep, or rest. Too much tamas, however, results in a mind that feels like it is covered by a thick, dark cloud.

In the diagram with the 25 Tattvas, the lower you go, the more tamasic it gets. The Mahabhutas (physical elements) are more tamasic than manas (lower mind), which is more tamasic than ahamkaar (the “I”-maker), which is more tamasic than buddhi (intellect).

Living organisms that display signs of conscious awareness are also explained through this framework. Sattva is reflective of the Consciousness that pervades the Universe (more on the specifics of this in a future article). When an object has sufficient sattva, it starts to reflect this Consciousness like a puddle of water reflects the moonlight. Otherwise, it appears inert. In this way, the mind is more sattvic than the body, which is more sattvic than a rock.

From the outside, Sattva and Tamas can seem very similar. To explain this, let us consider the example of a blender.

Remember old blenders, where you had to keep you hand on top to prevent them from shaking?

When the blender is turned off, it appears completely still. When it is turned on, but your hand is not on it, it shakes from side to side, and it is very clear that it is in motion. Now if you turn the speed up all the way, and cover it tightly with your hand, it will appear visibly still to an external observer (assuming the sides are opaque, of course), but in fact it is intensely active.

Similarly, a lethargic person and a highly sattvic Yogi can look similar from an external perspective - apparently peaceful, slow-moving, and calm. However, internally, they are worlds apart. The lethargic person will have a clouded mind, will be difficult to motivate, and will experience feelings of dullness, sadness, anxiety, or perhaps even anger (passive aggression is a prime example of tamas trying to disguise itself as sattva). On the other hand, the Yogi’s mind is completely clear, alert, with feelings of joy and peace, radiating love and compassion to those around them.

To clarify the gunas even further, here is a set of consecutive verses from the Bhagavad Gita that explains them through the idea of action:

Niyatam sangarahitamaraagadveshatah kritam. Aphalaprepsuna karma yattatSaatvikamuchyate.Yattu kamepsuna karma saahamkaarena va punah. Kriyate bahulaayaasam taddRaajasamudaahritam.Anubandham kshayam himsaamanapekshya cha paurusham. Mohaadaarabhyate karma yattatTaamasamuchyate.Sattvic action: Action that is virtuous, thought through, free from attachment, and without craving for the results.

Rajasic action: Action that is driven by craving for sense pleasure, done with pride/selfishness, and with stress.

Tamasic action: Action that is undertaken out of delusion, without regard to one’s own ability, without considering the consequences or potential loss or violence done.

- Gita 18.23-25

It is important to note that the proportion of gunas is not fixed, and changes from moment to moment. Further, we can consciously change the proportions of the gunas within us, and so increase sattva through our actions, if we wish to do so. Practicing meditation, eating Sattvic foods, cultivating Sattvic thoughts, and acting in a sattvic manner will make our minds more sattvic, and we can feel the effects first-hand. With more sattva, the mind will become more sharp, clear, calm, and joyful. Don’t just believe it - anyone can try this for themselves!

Ok, I get it, Tamas is bad, Sattva is good. Let’s all be more Sattvic, right?

Not quite.

Sattva is great if you’re trying to escape from suffering and “attain” Moksha, but rajas and tamas are the reason the world keeps turning. For the Yogi, Sattva is something to be sought after, but without an appropriate mix of rajas and tamas, society, and even the world, would no longer continue to function.

A beautiful (severely paraphrased) myth from the Vishnu Purana illustrates the necessity for this balance:

In the beginning, Brahma (the creator deity, not to be confused with Brahman, the Absolute Reality) decided to create a world. From pure sattva, he created 9 men and 9 women to inhabit the world. Due to the predominance of sattva, they all saw beyond the lure of desire, took to asceticism, and the society did not continue beyond the first generation.

Learning from his mistake, he decided to use rajas. Here, the people quickly annihilated each other from the intensity of their activity and selfishness.

Then, he tried to use tamas. Again, the society did not continue beyond the first generation, but this time due to sloth and apathy.

Finally, he decided to combine the three gunas and push them just slightly out of equilibrium. Thus, we have the world which we now inhabit.

While Sattva promotes clarity, peace of mind, and joy, Rajas and Tamas are critical to the continuation of existence and are not to be looked down upon. When embarking on the journey that is Yoga, while our personal goal may be to maximize Sattva, we must be thankful to those who are more Rajasic or Tamasic in nature for providing us with the environment in which to practice, and for keeping up the game through which we arrived at Yoga in the first place.

Next time: Purusha, the Pure Eternal Consciousness.

If you have any questions, comments, or feedback, please feel free to use the comments section below!