The Prescription: Part II

The Lion's Backward Glance: Classifying mental activity, obstacles to Yoga, and the twin foundation

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Anyone can practice Yoga1 - there is no special skill, knowledge, or age needed to do so.2

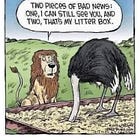

However, every mind is different, and so not all minds are immediately are ready to take it up as their goal in life. Very few are ready to listen, fewer are willing to study, and even fewer are ready to practice.3

For many who find themselves on the path, it can seem like the obvious choice. After all, everyone suffers, and everyone wants to stop suffering, right?

It is true that we all suffer, and it is certainly true that we all want to stop suffering. However, due to the presence of kleshas in the mind, not everyone has internally acknowledged the fact of suffering.

For most people, at any given point in time, the happiness derived from small pleasures is sufficient to keep them going, motivated to keep trying for the next thing. This manifests itself as the tendency to more easily spend significant time and attention on material pursuits - after all, it seems we will readily spend several years of study and hard work in school, college, or at work.

Yoga can only truly begin once the fact of dukkha - suffering - has been internally acknowledged, and once the Yogi has a sufficiently burning desire to break free.

This is why it can often feel like trying to communicate the final teachings with those around us can be an exercise in futility, and why it is important to first listen carefully for a burning desire before jumping into sharing. It is not a normal topic of conversation, rather, it is the way out of all misery - the most precious of all knowledge.

Additionally, as practitioners, we must be watchful of the ahamkaar appropriating the teachings, or seeing ourselves as somehow “better” than those who may not be practicing just yet.

Over the past 107 weeks, we have been discussing the method of Raja Yoga - the path of meditation, and one of the four possible paths to Freedom. The four Yogas are not limited by tradition, country, language, or history. Rather, they are each found in all of the world’s great traditions.

Last week, we began our review of the distance we have covered - the Lion’s Backward Glance, or singha-avalokana-nyaya.

Just as a lion walking through the forest stops and majestically gazes upon the distance it has traversed, we are here, looking back upon the understanding we have gained. This is the prescription for the diagnosis of dukkha - the feeling of incompleteness, or the “bumpy ride” nature of life.

As always, please reach out with any questions that may help clarify your understanding. Although I may take some time, I will try my best to respond to every question that is received. Some may even make it to future articles!

As a brief recap, last week, we reviewed the four purposes of life, the four Yogas, the classification of the experienced Universe into 25 categories called Tattvas, as well as the first method in Yoga - a classification of the ground, or bhumi, of mind. You can find last week’s article here:

This classification of your bhumi is critical to being able to measure your progress. Without a stake in the ground, you will have a difficult time knowing how far you have come.

This week, we will continue our singha-avalokana-nyaya, looking over the method to classify mental activity, and the twin foundation of Yoga. Then, starting next week, we will review the foundational techniques, Kriya Yoga, and the eight limbs.

How to classify your mental activity

The mind can be thought of as a lake. The lake can be muddy or clear, and it has ripples on its surface.

In this analogy, every time an object is brought forth to the mind, it is like a rock being thrown into the lake, leaving ripples that expand outward.

These ripples are called vrittis - literally “whirlpools” or “modifications.”

These vrittis can be coloured or uncoloured - dirty or clean. When they are coloured, they result in dukkha, when they are uncoloured, they are benign.

The goal of Yoga - its very definition - is the mastery of these vrittis. All the practices - from the foundational techniques to Aasana, from breathing techniques to meditation - are for this purpose.

At the beginning, the mind is like a turbulent, muddy river near its mouth as it torrentially pours into the sea. The goal is to make it clear and calm, like a pristine Himalayan stream. Less vrittis, with no kleshas - no waves, no mud.

Vrittis: Mental whirlpools

All mental activity - all whirlpools or ripples in the lake of the mind - can be classified into these five categories:

Pramaan (प्रमाण): Evidence

Viparyay (विपर्यय): Error

Vikalp (विकल्प): Imagination

Nidra (निद्रा): Deep sleep

Smriti (स्मृति): Memory

For example, as you read these words, what you are actually experiencing is a series of pramaan-vrittis in your mind. However, you are also experiencing an additional vikalp vritti - the voice in your head that is reading these words.

Now try to think back on your last meal - what did you eat?

This is a memory - smriti - a recollection of a past vritti.

The first category, Pramaan, is further classified into three categories:

Pratyaksh (प्रत्यक्ष): Direct perception

Anumaan (अनुमान): Inference

Aagama (आगम): Trusted testimony

These are not a diktat, a la “only this counts as valid knowledge.” Rather, it is an observation of what we normally consider to be valid knowledge.

Normally, when we sit down to meditate, we are swept away by the torrent of thoughts in the mind. We get attached to particular thoughts, and ride along with them to the next thought, like a monkey swinging from one tree to another.

This framework can be used to categorize thoughts by their nature, rather than by their content, thus freeing the mind from its normal tendency to swing from one thought to another, and allowing thoughts to rise and settle without ignoring them.

For more on the vrittis, take a look at the article here:

Kleshas: Mental colourings

Have you ever noticed that some things are more memorable than other things? Some perceptions, memories, imaginations, and even illusions leave a deeper impression on the mind than others. What’s more, some mental happenings are more painful than others, causing us to suffer either in the immediate or long term. Why is this the case?

In Yoga, this is due to the presence of kleshas - mental afflictions, or colourings.

The vrittis - the mental whirlpools described in the section above - can be coloured (klishta) or uncoloured (aklishta). These kleshas are of five types:

Avidya (अविद्या): The Primal Ignorance

Asmitaa (अस्मिता): “I am”-ness

Raag (राग): Attraction

Dvesha (द्वेष): Aversion

Abhinivesha (अभिनिवेश): Fear of discontinuity/Clinging to continuity

The root of all of these kleshas, and indeed of all suffering, is avidya. Avidya is like a field from which all the other kleshas grow. As a result, while the other kleshas can be weakened through the various techniques in Yoga, they can only be removed by removing the underlying avidya.

Avidya manifests in the form of four fundamental confusions - four ways in which we unconsciously lie to ourselves about the nature of reality:

Confusing the impermanent to be permanent

Confusing the unclean to be clean

Confusing suffering to be pleasure

Confusing non-self to be Self

For more on the four confusions, you can take a look at the articles here:

There are many methods to remove avidya - these methods are classified as the four Yogas. In fact, Yoga is, in essence, any method which removes avidya.

Asmitaa is the next klesha to arise. Any time you think that something is “me” or “mine”, it is a colouring of asmitaa over that vritti. For example, if you think the device on which you are reading this is “my phone” or “my laptop”, what is happening in the mind is a pramaan-vritti of your phone, coloured with the klesha of asmitaa. This is also true for the identification with the body - we think “I am” this body because the pramaan-vritti of the body is coloured with the klesha of asmitaa.

Once avidya and asmitaa are present, only then can the next three kleshas arise - attraction, aversion, and fear of discontinuity.

The kleshas can combine to form what we experience as complex emotions. As an example, take a look at the diagram below for a breakdown of “regret” into vrittis and kleshas.

Finally, when they are present, these kleshas can appear in various degrees of strength or intensity. Specifically, the four degrees of strength are:

Udaar (उदार): Strong

Vichhinna (विच्छिन्न): Interrupted

Tanu (तनु): Weak

Prasupta (प्रसुप्त): Dormant

For more on the degrees of strength of kleshas, take a look at the article below:

All of Yoga can be framed as a systematic method to weaken these kleshas and ultimately destroy them completely. Different techniques are suitable for different degrees of strength. This is why for some people meditation can seem more difficult than for others, and for some people the teaching seems to go in one ear and out the other.

To solve for this, we must first focus on ourselves, experimenting with various techniques to see what is most effective for us, and practice the others systematically. All techniques serve different purposes, but the starting point may be different for different minds. It is generally best to start at the beginning.

Obstacles to Yoga

Not everyone is ready for Yoga, and this lack of apparent readiness is due to one or more of nine factors, known as antaraayaah - “obstacles” or “interruptions.” However, even for Yogis, these nine obstacles are present in the mind to different degrees until the final Kaivalyam. The obstacles are:

Vyaadhi (व्याधि): Disease

Styaan (सत्यान): Mental coagulation/heaviness

Samshaya (संशय): Doubt

Pramaad (प्रमाद): Carelessness

Aalasya (आलस्य): Sloth

Avirati (अविरति): Desirousness

Bhraanti-Darshan (भ्रान्तिदर्शन): Misapprehension

Aalabdha-Bhumikatva (आलब्धभूमिकत्व): Inability to find a base

Anavasthitva (अनवस्थित्व): Instability/Inability to maintain a state

Normally, we feel that some external situation results in negative feelings, which results in mental scattering, which finally results in one or more of these obstacles. Yoga flips this on its head. If we closely observe, we will find that these obstacles cause mental scattering, which then leads to negative feelings.

These “negative feelings”, known as accompaniments are:

Dukkha (दुःख): Sadness/Distress

Daurmanasya (दौर्मनस्य): Dejection/Frustration/Melancholy

Angam-ejayatva (अङ्गमेजयत्व): Anxiety (literally, trembling of the limbs)

Shvaasa-Prashvaasa (श्र्वासप्रश्र्वासा): Irregular breathing

The accompaniments are generally easier to identify, even in another person. Once the accompaniment is identified, the specific obstacle then needs to be overcome.

For more on the obstacles and accompaniments, you can take a look at the article here:

The Twin Foundation of Yoga

Yoga is built atop a twin foundation of two complementary principles - practice and letting go, force and release - abhyaas and vairaagya.

Every single technique in Yoga requires both of these principles in order to be successful. Without them, it is easy to get stuck in a rut of trying various different techniques with minimal or slow results. Keeping these two in the back of your mind throughout your life is like a cheat-code to get quicker and better outcomes.

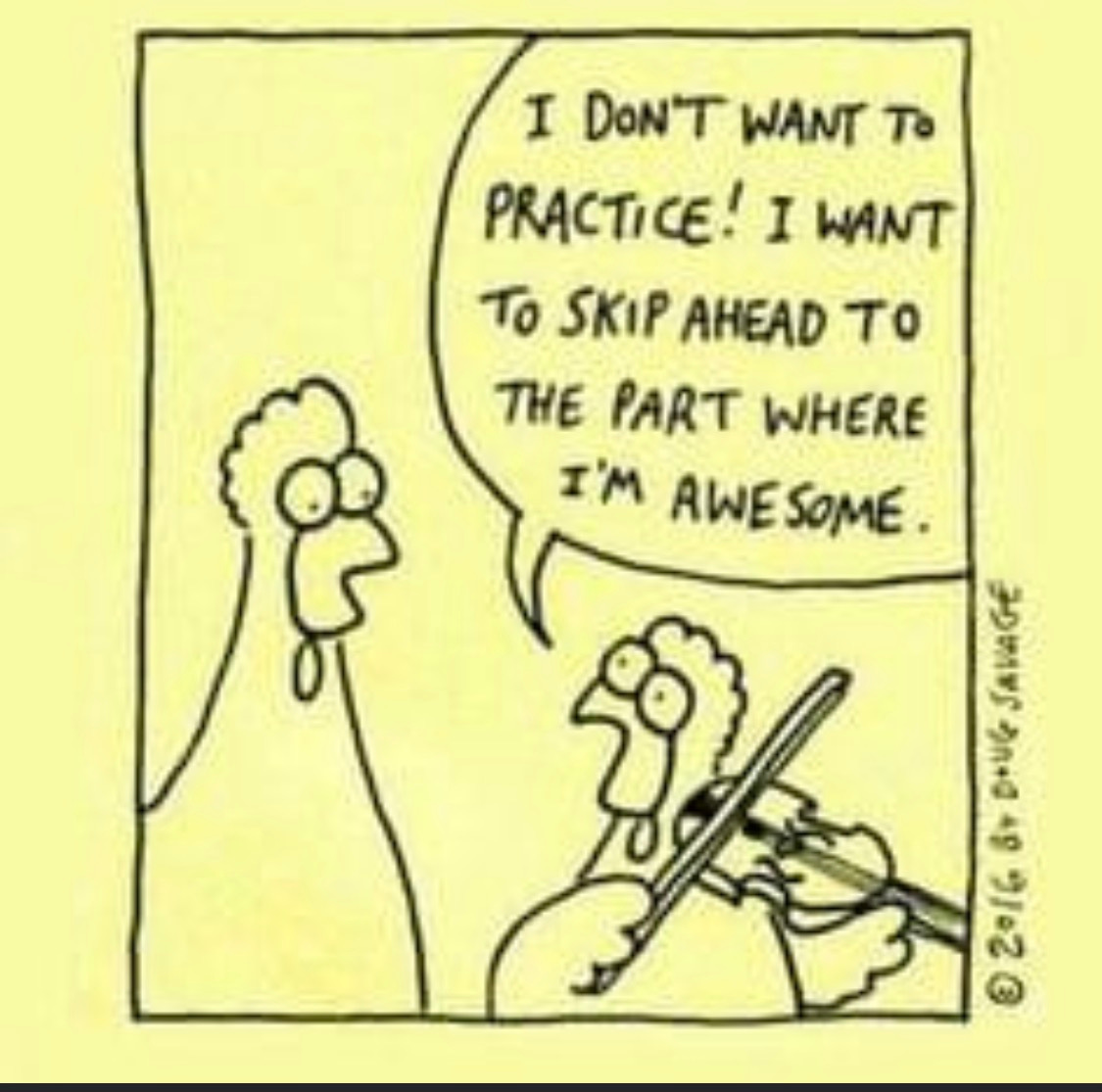

Abhyaas: Practice

The mind can be compared to a field of soil, and the Yogi to a farmer. When a farmer wants to create a channel in the soil to irrigate a particular set of plants, they pour water over the soil. As water is poured repeatedly, a channel starts to form. Every subsequent time the water is poured on that part of the soil, the channel deepens, until eventually, even if water is poured near the channel, it falls into the channel and flows in the intended direction, effortlessly.

Yoga - and further, all skill - is just like this. The more we practice, the easier it gets.

In the context of Yoga, however, practice specifically refers to the repetition of those things which bring stability to the mind.

It is a common misconception that we must practice those things which make our mind peaceful. This seems good on the surface, but can lead to selfishness - we start to ignore or hide away from things that make us feel unpleasant, even when they are necessary.

Rather than peaceful, the goal is to practice those things which make the mind stable. That is, unaffected in the face of any situation - good or bad. This subtle distinction can make all the difference.

Once we understand what practice means in the context of Yoga, and if we are resolved to practice, we naturally want our practice to be effective and efficient. Yoga provides a framework for this, which works even outside of the context of these techniques.

Specifically, in order for practice to be effective, there are four keys:

Deergh kaal (दीर्घ काल): Long time

Nairantarya (नैरन्तर्य): Relentlessly, without a break

Satkaar (सत्कार): With devotion, sincerity, internal honesty

Aasevitah (आसेवितः): With careful attention

We should expect that results will not come instantly. Additionally, we must practice relentlessly - in meditation, as well as in day-to-day life. Third, practice must be sincere - we must be honest with ourselves, otherwise it is easy to delude ourselves into thinking that we have made more progress than we have. Finally, we must practice with careful attention - the more mindful our repetition, the higher the chances of our desired outcome.

The more each of these keys is followed, the quicker the results will come. However, even a little bit of practice goes a long way.

For more on the four keys to practice, take a look at this article:

Vairaagya: Letting go

In the example of the farmer and the field, the soil is fresh - that is, there are no channels already present for water to flow through. However, our minds are not fresh in this way. We already have tendencies, often very strong ones. For example, we may have a tendency towards distracting ourselves when we feel sad, or a tendency towards anger. On the other hand, we may have a tendency towards generosity, or truthfulness.

Some of these tendencies are more useful than others.

P: What do you mean by “useful”?

Jogi: In the context of Yoga, “useful” tendencies are those which bring stability to the mind.

In this way, the whole project of Yoga is not only to create new channels in the soil of the mind, but also to remove existing channels that do not serve us. While abhyaas helps us create new channels, it does nothing to remove old ones.

This is where vairaagya comes in.

Vairaagya is not a “doing,” Rather, it is a “non-doing.”

P: That sounds awfully cryptic - what does it mean?

When the farmer is pouring water in one area, they are not pouring water in other areas. That is, they are practicing abhyaas in one area, but vairaagya in another.

Normally, we pour our attention on objects indiscriminately. Whatever appears - thoughts, perceptions, imaginations, etc. - we pour our attention all over it. This creates channels in the mind, which then makes it easier for attention to flow to those objects more easily.

If, instead, we are mindful about where we place our attention, we slowly weaken those channels, allowing our attention to flow more fully where we want it to. This “not pouring” of water is vairaagya - letting go of the mental tendencies by mindfully not placing attention on them.

In order to go away from the North, all you need to do is go South. It is one action, not two. You don’t need to go away from the North and go towards the South - it is a single movement.

In the same way, vairaagya is not an act in itself, but rather a mental attitude that allows you to let go of thought patterns without jumping on to every train of thought that comes your way.

For more on vairaagya, take a look at the article here:

TL;DR

This week we continued our Lion’s Backward Glance - the singha-avalokana-nyaya - on the path of Raja Yoga that we have been discussing in detail over the past 107 weeks. For the first article in the series, take a look at the link below:

Last week, we went over the purpose of life, the four Yogas, the method of classification of the experienced Universe into the 25 Tattvas, and we reviewed the 5 Bhumis, or grounds of mind.

In this article, we went over the method to classify mental activity - vrittis (mental whirlpools), and kleshas - the nine obstacles, four accompaniments, and the twin foundation of Yoga - practice and letting go.

These fundamentals are absolutely critical to deeply understanding Yoga, and being able to tailor your own practice for your own needs.

Next time, we will begin a discussion on the foundational techniques, Kriya Yoga, and, perhaps, the eight limbs.

As always, please reach out with any questions that you feel will be helpful for you to gain a better understanding, or that may help to strengthen your practice. All questions from all levels are welcome, and you can remain anonymous if you so please.

Next time: The Prescription: Part III

Raja Yoga

This is unlike Jnana Yoga, where there is a fourfold set of qualifications required in order for the method to be even remotely effective.

This is not to say that all minds will not be ready for Freedom at some point.