Question everything

The 5 Niyamas: Svaadhyaay

Note: Click on the title above to view the full post in your browser.

Ask your questions anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup.

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

अनन्तपारं किल शब्दशास्त्रं स्वल्पं तथायुर्बहवश्च विघ्नाः। यत्सारभूतं तदुपासनीयं हंसैर्यथा क्षीरमिवाम्बुमध्यात्॥AnantaPaaram kila shabdaShaastram svalpam tathaAyurBahavasCha vighnaahyatSaaraBhootam tadUpaasaneeyam hamsairYathaa ksheeramIvaAmbuMadhyaatThere are, indeed, infinite books [to read], but the life span is short, and there are many obstacles. Therefore, be like the swan that can sift milk from water, and extract only the essentials [discarding the rest]1.

- Mahasubhashitamsangraha

For the past several weeks we have been discussing the Niyamas - the second limb of Yoga. This limb deals with personal conduct, adjusting it in such a way that it sets the Yogi up for success in future limbs, and simplifying it so that it is no longer a distraction. In essence, it is a method of creating fertile ground for the Yogi to move further inwards, towards the Self.

The mind is naturally tilted towards the objects of the world. We are distracted by objects of all kinds - money, power, pleasure, success, righteousness, love and so on. We run after objects, desiring fulfilment, only to find that no matter how many objects we gain, we remain perpetually unfulfilled.

This tendency to run after objects stems from avidya, the root cause of all the other kleshas, and - crucially - of all suffering. As a result, if we want to get rid of suffering, we must first get rid of avidya. This removal of avidya, or freedom from suffering is known as Moksha (aka liberation, enlightenment, awakening, etc.). This is the goal of Yoga.

Now Moksha is not an object like other objects. It is our current state, right now, but it is hidden from us.

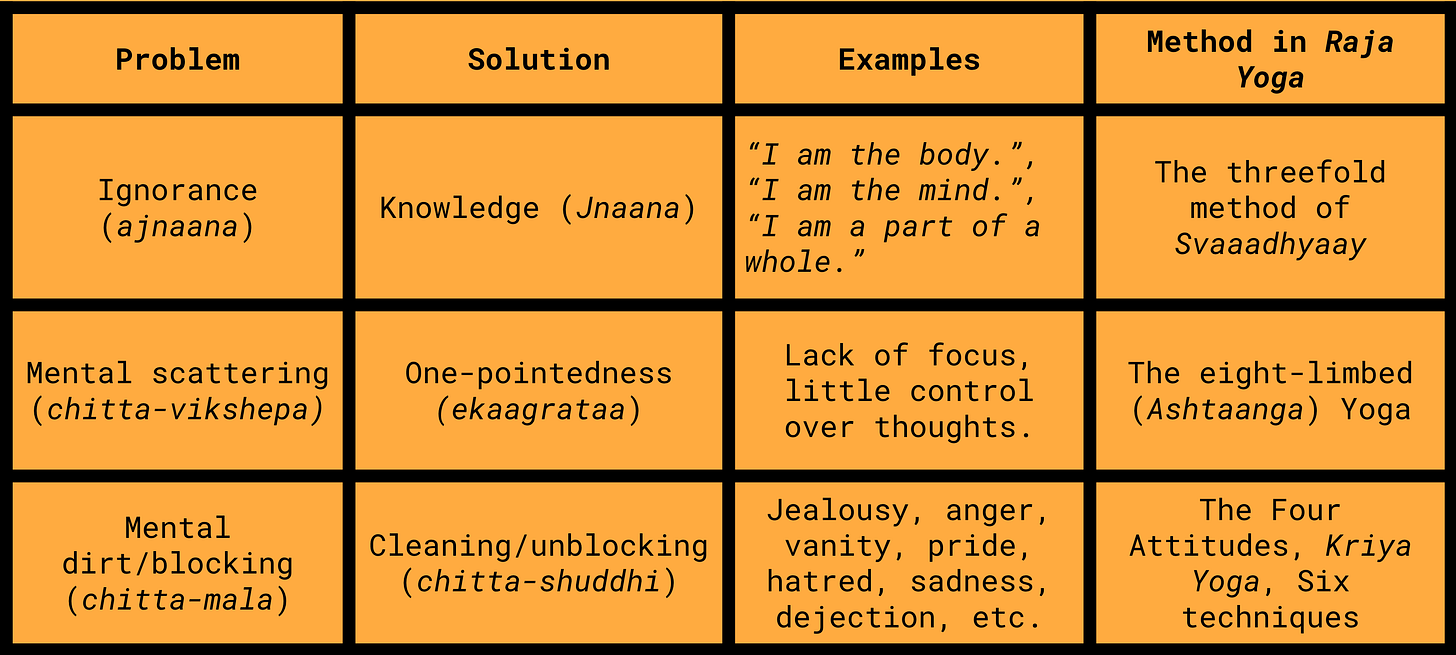

Specifically, it is hidden by three barriers:

Chitta-mala: Mental dirt

Chitta-vikshepa: Mental scattering

Ajnaana: Ignorance

Chitta-mala (literally “mental dirt”) includes such things as jealousy, pride, vanity, anger, hatred, and so on. These are solved by the preliminary practices of Yoga such as the four attitudes (benevolence, compassion, gladness, and equanimity).

Chitta-vikshepa is the next barrier. Literally, it means “mental scattering”, and can be directly seen in our lives when the mind feels distracted, moving from one thing to the next in quick succession. This is solved through meditation, and through the practice of the eight-limbed Yoga (which we are currently discussing).

Finally, we have ajnaana (pronounced uh-gyaah-nuh) - literally, ignorance. This is similar to avidya, except that it applies to all objects, not just the body-mind. Simply said, ajnaana, when applied to the individual body-mind, is known as avidya.

The solution to any ignorance is knowledge, and so the solution to this final barrier is a special type of knowledge - knowledge of the Self. The method to gain this knowledge is called svaadhyaay, or Self-study. This is the the fourth Niyama, and will be the subject of our discussion today.

Svaadhyaay: Self-study

स्वाध्यायाद्योगमासीत योगास्वाध्यायमासते |SvaadhyaayaadYogamAaseet yogaaSvaadhyaayamAasateFrom Svaadhyaay comes Yoga, and from Yoga comes Svaadhyaay.

- Vyasa’s commentary on Yoga Sutra 1.29The word “svaadhyaay” literally means “Self-study” (sva + adhyaay = svaadhyaay). Normally, it simply means studying by oneself, as one may study for an examination. However, in this context it also means studying such material where the subject matter is the Self.

Taking these two meanings together, Svaadhyaay, in Yoga, is the self-study of moksha-shaastras (soteriological texts), or any material that deals with the subject matter of liberation.

Yoga is non-sectarian, and so Svaadhyaay can be the study of any such text, regardless of the tradition from which it comes.

As with Tapas and Ishvarpranidhaan, it is one of the three aspects of Kriya Yoga - a preliminary practice to the eight-limbed Yoga aimed at making it easier for the practitioner to practice. If you ever feel like it is hard for you to meditate, or if it is difficult to practice the earlier limbs of the eight-limbed Yoga (e.g. the Yamas and Niyamas), these preliminary practices are tremendously helpful. For more context on Kriya Yoga, you can take a look at the articles here and here.

As a Niyama, the goal of Svaadhyaay is four-fold:

To increase will-power (ie. to strengthen the buddhi)

To reduce the effect of the kleshas (ie. the colourings/afflictions in the mind)

To increase mumukshutvam (the longing for liberation)

To remove ajnaana (ignorance resulting in the appearance of the manifold Universe)

Like all the Niyamas, there are two ways in which to practice svaadhyaay - as a mahaavrat (ie. in all times, in all places, in all circumstances), and as conditioned by time and place (ie. once/day, twice/day, etc.). As with tapas, this does not mean that one must choose between these modes of practice, but rather that they are complementary to one another.

Following are the two approaches to svaadhyaay.

As conditioned by time and place

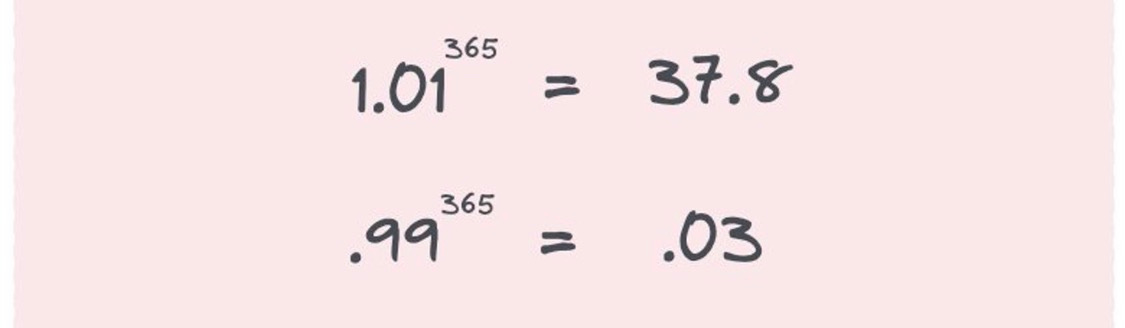

As a conditioned practice, svaadhyaay means that you study a little bit every day. This way, over time, your knowledge increases. As knowledge increases, the Yogi can use it to improve their own practice, and to understand their own nature in such a way that leads them towards liberation.

Every individual is different, and so self-study is a way of helping the student find their own path, at their own speed, by gaining their own wisdom, rather than by relying on the authority of others.

Often, when others learn that you are a practising Yogi, people may ask - “who is your teacher?” or “whom do you follow?”

This line of questioning indicates that the questioner may be in search of some authority in whom to believe. While this is a natural inclination, it is problematic in the Yogi, because it indicates a certain mental laziness - one does not want to spend time investigating for themselves, and so they look to an authority to show them.

While this may be helpful to some degree, when it comes to Self-Knowledge, one can only truly see the truth for themselves if they put in the effort to seek the truth for themselves.

If you do not seek the truth of your own accord, any teachings - no matter how qualified the teacher may be - will be nothing but empty words.

The goal of Yoga is Knowledge of the Self - it is a search for Truth, and as such has no place for reliance on blind faith. Knowledge of the Self, of God, or Moksha must be known by direct experience - otherwise what purpose does it serve?

In this way, svaadhyaay, or Self-study is critical for success in Yoga. Study on your own, passing all learnings through your own filter of judgement, questioning everything until, to quote Swami Vivekananda, “it tingles in every drop of your blood.”

Additionally, even a few minutes of svaadhyaay every day ensures that you will know significantly more over time.

Finally, through regular study and application of the texts to one’s own life, the identification with the body and mind is weakened, and as a consequence, so are the kleshas that stem from this identification.

The study of this kind of material also leads to a weakening of one’s interest in worldly affairs and in the desire to chase objects, and increases the Yogi’s interest in Realization.

In terms of Yoga psychology, svaadhyaay is simply a method to intentionally shift of samskaaras (mental tendencies) towards the Self, and away from the objects of the world.

How should I study?

Svaadhyaay follows a systematic threefold method. While in this context it is applied to the moksha-shaastras (soteriological texts), this method can be applied to learning anything at all:

Shravana: Listening

Manana: Doubting

Nididhyaasana: Assimilating

Shravana: Listening

Shravana (pronounced shruh-vuh-nuh) is the first step of svaadhyaay. This means that you read or listen to the teachings carefully, and with full attention, in such a way that you are able to at least repeat what was said with some level of understanding.

Traditionally, novice monks are expected to recite the teachings from memory in the original Sanskrit, but as long as you are able to explain what is said in your own words, that is sufficient for this stage.

Here, there is no question of believing, not believing, agreeing or disagreeing. It is simply a matter of being able to repeat what is said, with an understanding of the meaning.

Manana: Doubting

Manana (pronounced muh-nuh-nuh) is the second step of svaadhyaay. Here, you have already heard the teachings, and are able to repeat them back as they were said.

At this point, focus your attention on finding the areas where you disagree. Does it fall in line with your own observation? Is there something which you find objectionable? Why don’t you agree?

Take note of these questions so that you can answer them yourself, or ask someone who may be able to help point you in the right direction.

If you decide to ask someone, do not believe them just because they said it, or just because you feel that they are some sort of authority. Question any response you get rigorously, and remain intellectually honest. If something requires blind faith, reject it outright. There is no room for belief in this stage, because where there is belief, there is room for doubt.

Note: There are some in the Yoga community, especially in the West, who have started to question science without a thorough understanding of science, especially when it comes to the pandemic. This is an excellent example of how not to question. In order to properly object to a proposition, one must first thoroughly understand it. In absence of a complete understanding of the proposition, an objection is invalid (ie. if you don’t understand what you disagree with, your disagreement makes no sense).

With the example of the pandemic, one must first understand how scientific research works (ie. the scientific method, experimentation methods, peer-reviewed research, etc.), then understand the basis of the research (ie. the underlying evidence), and the subject matter (here, immunology and virology). In absence of a complete understanding, it becomes a question of erring on the side of non-violence and compassion towards others (a weakening of avidya), versus a selfish desire to save one’s own body-mind oor to seem more intelligent than the crowd (either way, a strengthing of avidya).

The goal of manana is to rigorously and unapologetically eliminate all shreds of doubt, until there are no more questions to be answered.

You know you are approaching the end of this stage when you have no doubt that the teachings are true, and have questioned them from all angles.

This stage requires tremendous energy. The Yogi at this stage must be focused on finding the Truth. Simply agreeing with authority because it is easy (e.g. my Guru told me this, or Jesus Christ or Swami so-and-so said this) will not do, because that will leave gaps in understanding which will fester, eventually leading the Yogi away from their practice. One of the obstacles to Yoga is samshay, or doubt. Make sure to cut down your doubts as they arise, relentlessly. If you do not find the answer, do not give up - keep searching.

Something to note here is the importance of shraddha, or conditional faith. It is not the same as blind faith. One can consider an example of a class at a school or University, where the professor is explaining some complex topic. You may not have directly experienced what they are teaching yet, but you do not doubt that they are telling you the truth. You ask questions so that you understand, rather than walking out of the class or insulting the teacher every time the teachings escape your current understanding, or if you disagree at first glance.

This conditional faith that the teachings are not lying to you, and that although you may disagree at first, it is possible that you have just not yet understood, is called shraddha.

It is a form of intellectual humility - an acknowledgement that you do not yet understand, but by asking the right questions, the understanding will come to you.

Without shraddha, every time you do not understand something, you would simply reject it. The teachings are often complex or difficult to understand. As a result, the lazy (ie. tamasic) or restless (ie. rajasic) mind may try to throw them out and look for something else to run after. Instead, retain your focus, and continue to question until the answer reveals itself.

Do not give up on finding the answers to your questions - they have been debated for thousands of years by some of the greatest minds known to humankind. The answer is there, just perhaps not in your view.

Nididhyaasana: Assimilating

Nidhidhyaasana (pronounced nih-dih-dhyaah-suh-nuh) means a constant contemplation, remembrance, or assimilation of the teachings. Once all your questions have been answered, repeat them again and again, until they become absolutely real to you. Even after all your doubts have been dispelled, it is common that the teachings still feel somewhat theoretical. It is here that nididhyaasana is practiced.

Specifically, apply the teachings to yourself, right now. Rather than considering thought constructs (e.g. the “Self” as an idea), apply it to You.

For example, one teaching may be that the “body” is a mental construction. You may understand this theoretically, but with nididhyaasana, you would then apply the line of reasoning to your own body. Watch carefully how your breath goes in and out, and how there is no place at which you can demarcate the edge of your body. Watch how your food turns into your body as you eat it, and becomes “not-body” when you excrete it. Constantly contemplate the teaching in your day to day life, until you see with clear eyes that the body is truly just a mental construct.

This kind of constant contemplation on every teaching is the method of nididhyaasana.

P: Ok, I’ve understood the threefold method of Self-study. But what do I actually study? Is there some sort of syllabus?

What should I study?

As a practical matter, here is a list of texts (all free) that you can use to practice this aspect. This list only includes texts based in Advaita Vedanta (non-dual Vedanta), but one can use texts from any tradition for this purpose. Yoga is non-sectarian, and provides a framework to practice the teachings of any tradition.

Specifically, however, svaadhyaay does not include texts about morality, mythology, or faith. If you are from a different tradition, search for the esoteric or mystical school associated with it in order to find appropriate material (e.g. For Islam - Sufism; for Judaism - Kaballah; for Christianity - Gnosticism; for Buddhism - Dzogchen, Zen, Madhyamaka-Shunyavaada, or Vajrayana).

In Advaita Vedanta (which this series is based on), the texts themselves can be broken down into the three categories of learning. There are many, many more texts, but a few have been listed here as an initial reading list. Each text is said to be sufficient for Realization unto itself. However, the more one reads, the more they will understand.

Finally, for a point of view that does not require blind faith (and that will be in line with what you may find here on Empty Your Cup), look for commentaries by Adi Shankaracharya, with translations from his lineage of monks. The Ramakrishna Order in particular has done an excellent job of making these texts easily available over the past century or so.

Read the texts carefully, using the four keys to practice, letting go of any strongly held beliefs, and following the threefold method outlined above, but do not fall into the temptation to believe anything blindly, just because it is written in so-called “holy books.”

“Avoid beliefs - Hinduism, Islam, Christianity. Seek on your own. You may come to find the same truth. You will come, because the truth is one. Once you have found it you can say: Yes, the Bible is true - but not before. Once you have found it you can say: Yes, the Vedas are true - but not before. Unless you have experienced it, unless you become a witness to it personally, all Vedas and all Bibles are useless. They will burden you, they will not make you more free.”

- Osho

Texts for Shravana (initial learning)

These texts are often known as Prakaranagranthas, or “introductory texts”, although they are actually fairly advanced. If you are completely new to this material, do not skip over the introductions written by the translators. There are a lot of texts like this, but to start, here are a few:

Texts for Manana (doubting and reasoning)

This category of texts is generally extremely dense, with difficult logic, with several objections and responses. It is far easier to read these once you have some background from the first category of texts:

Texts for Nididhyaasana (assimilating)

These texts do not have any logical argumentation, nor any definitions. They are more like poetry, with each verse providing a different angle at the same teachings. With these, one may consider reading a single verse repeatedly, reflecting on it intensely throughout a given day.

Core texts, can fall in all categories

This category is called the Prasthaanatrayi (literally the “three sources”), and form the traditional canon of Vedanta. They can be used in any of the above categories of reading. However, these are common to all the Vedantic traditions - not just Advaita Vedanta. As a result, some translations often have a devotional slant. This is not bad, but for the purposes of understanding Advaita Vedanta systematically, one may begin with Shankaracharya’s commentaries. They are:

The Upanishads (aka Sruti-Prasthaana, or the “revelation source”): These are found in the Vedas, and are the revelations of the ancient rishis, or seers. There are over a hundred Upanishads, but ten (or eleven, if you count the Shvetashvatara) of them have been commented upon by Adi Shankaracharya, and are widely considered the principal Upanishads. They are:

The Brahma Sutras (aka Nyaya-Prasthaana, or the “logic source”): This is also known as the Vedanta Sutras. This is a lengthy and extremely dense text of 555 sutras, composed by the Sage Badrayana, but is sometimes attributed to Vyasa.

The Bhagavad Gita (aka Smriti-Prasthaana, or the “remembered-tradition source”): It is said that the Upanishads are the cow, Krishna is the cowherd, the calves are Arjuna and other students of Vedanta, and the milk is the Bhagavad Gita.

Other resources

Aside from reading, there are also several teachers whose talks you can find online. When listening to a teacher, it is important to remember not to blindly believe what they say, or to put them on a pedestal. Teachers, like us, are products of prakriti (nature). Take their words without taking into account your impression of the speaker, and pass all teachings through the filter of your own intellect. As with reading, use the same threefold method of shravana, manana, and nididhyaasana (listening, doubting, and assimilating) described above, and ask questions relentlessly.

Some teachers whose talks you can find on YouTube are:

Practicing svaadhyaay as a mahaavrat

As a mahaavrat, the practice of svaadhyaay means to constantly remind yourself of the teachings, and to ruthlessly question everything that you might normally take for granted. For example, that You are not the body, You are not the mind, but rather they are just appearances in You as waves appear in water, or as a pot appears in clay. We will get more into this particular topic when we discuss Advaita Vedanta in future articles, but for now consider it to be a constant reminder to oneself regarding the four confusions of avidya.

In particular, they are:

Confusing the Impermanent to be Permanent

Confusing the Unclean to be Clean

Confusing Suffering to be Happiness

Confusing Non-Self to be Self

The goal here is to be constantly aware of your mental activity, so that when you find yourself falling prey to one or more of these four confusions, you remind yourself of the facts. For example, if you find yourself clinging to an object in your experience - positive, negative, or neutral - remind yourself that it is impermanent, and it will pass.

If you find yourself feeling pride, jealousy, vanity, anger, etc., remind yourself that it stems from an attachment to the body and the mind, which are just objects in Your experience, like any other, and that they do not belong to you.

Essentially, svaadhyaay as a mahaavrat (practice in all times, in all places, etc.) is to take the teachings off the page, and bring them into our daily lives.

To make this clear, let us consider another example. We have discussed how avidya manifests in our minds as a deep-set habit of classifying our experiences into “objects.”

Now as a result of this habit, we do not deeply see anything once it has been classified. We may see, (or otherwise sense) many things, but due to the mental habit of “objectifying”, we don’t give more attention to our experiences than is needed to objectify them. For example, right now you know that you are holding your phone, laptop, or other device, but are you really paying close attention to the details of the screen? To each pixel of these words? To the tactile sensation of your fingers on the device? What about to your breathing - how it is cool when you breathe in but warmer as you breathe out?

Due to this habit of objectification, we end up living in a world of symbols, and as a result feel a sense of hopelessness, emptiness, or shallowness in our lives.

On the other hand, if we were to truly pay attention to everything around us - without objectification - we would feel a sense of constant wonder and the multi-dimensional technicolour display that we otherwise emptily refer to as “the world.”

Paying attention closely in this way would be a method of taking the teaching around avidya off the page and into one’s daily life.

In this way, through these constant reminders of the teachings, the Yogi builds up mental impressions that help them along toward the goal of Yoga, eventually leading to a much calmer mind and greater feelings of fulfilment and joy.

Some commentators also mention that svaadhyaay includes the recitation (aka japa, pronounced jup-uh) of mantras. In the “Hindu” traditions, these are often Sanskrit sounds or phrases with specific meanings, and japa is a method of reciting the mantra repeatedly (mentally or verbally) bringing the meaning to mind.

However, like with anything in Yoga, it is not limited to the “Hindu” traditions, but can be extended to any of the world’s traditions. Some common mantras are Om, Om Namah Shivaay, Om Namo Bhagavate Vaasudevaaya, Om Mani Padme Hum in Buddhism, Subhaan Allah in Islam, the Mool Mantra in Sikhism, or the Lord’s prayer in Christianity. The idea here is that one shifts their default thought from thoughts about the body-mind to one of these mantras.

Normally, when the mind is idling (ie. when you’re just sitting and doing nothing), it rushes along familiar patterns. These may be patterns of worry, sadness, anxiety, thoughts about work, family, friends, or anything else. The idea with this kind of svaadhyaay is that with practice, when the mind is idling, it automatically starts to repeat the mantra that you have chosen. This leads the default state of the mind to be calm and focused, rather than scattered and turbulent.

The result of svaadhyaay

As with all the Yamas and Niyamas, there is a companion sutra that describes the result when the Yogi is established in svaadhyaay.

स्वाध्यायाद् इष्टदेवतासंप्रयोगः ।Svaadhyaayaat ishtadevataaSamprayogahFrom Svaadhyaay comes a connection to [the Yogi’s] ishta-devataa.

- Yoga Sutras, 2.43

In order to understand this, we first must understand the concept of an ishta-devata.

Consider the abstract concept of “colour” (or if you are unable to see, consider “sound”). Due to your experience in life, you have seen many objects with colour, and so you now understand what “colour” means in the abstract. Had you never seen a colour, you would not be able to grasp the meaning.

God, in Advaita Vedanta, is without name, without form, and without attribute (we will discuss the specifics of what God is in later articles, but for now this should suffice). In a manner of speaking, the purpose of Yoga is the direct experience and understanding of God. However, in order to truly understand an abstract concept like God, we must first have a form through which we can expand our understanding. Without a form (physical or mental), the human mind cannot grasp meaning.

Even in the Abrahamic traditions, where God is formless, practitioners have a name in their mind, with qualities like “great”, “good”, “omniscient” and so on, and, if one is truly honest with themselves, some sort of mental form - even if it is more of a hazy idea in the back of the mind.

Given our mental incapacity to grasp anything with form, the world’s traditions provide several options to choose from. However, for the purposes of Yogic practice, it is helpful to choose a single form. This can be a name, a symbol, a physical form, or any combination of these.

While for some of us, we are born into a tradition and so it may be easier to pick one option, for many of us, this choice can be quite difficult. Making this choice in such a way that it sticks, and so the mind does not keep wavering between options is what this sutra is referring to.

Through the practice of svaadhyaay, there automatically arises a connection (ie. samprayog) in the mind of the Yogi to one form over others, allowing them to fine-tune their practice. This name, form, or symbol is known as the Yogi’s ishta-devataa.

Yoga is non-sectarian, and provides a framework within which we can better understand the traditions from which we may have more background, or to which we may be attracted. There is no compulsion to choose a “Hindu” name, form, or symbol. Rather, through the practice of svaadhyaay, the practitioner will automatically gravitate towards one of their choice - be it Allah (swt), Yahweh, Jesus Christ, Kali, Ganesha, Krishna, Shiva, Vishnu, Waheguruji, or even “the Universe.”

Until next time:

Start your svaadhyaay. Click on one of the links above, or choose a book from your own tradition, and start reading! Take notes as you go, carefully compiling any questions that you have. Do not be afraid to ask questions. Feel free to post them in the comments section here (or in any of the articles), by responding this email, or anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup.

If you feel like this guy in the meme below, don’t worry. Stay focused, and don’t waver. Do not fall into the temptation to move on without understanding - this is a lifelong practice, there is no rush to get through all of the texts, even in a single lifetime. What’s more, you will likely find that the more intensely you practice the other limbs of Yoga, the easier it will get to get through the teachings.

Next time: The Teacher of the Ancients: Ishvar

A similar verse also appears in the Panchatantra:

अनन्तपारं किल शब्द-शास्त्रं स्वल्पं तथायुर् बहवश् च विघ्नाः ।

सारं ततो ग्राह्यम् अपास्य फल्गु हंसैर् यथा क्षीरम् इवाम्बुध्यात् ॥ ६ ॥

anantapāraṃ kila śabda-śāstraṃ svalpaṃ tathāyur bahavaś ca vighnāḥ |

sāraṃ tato grāhyam apāsya phalgu haṃsair yathā kṣīram ivāmbudhyāt || 6 ||

There are infinite books to read, but the life span is short, and there are many obstacles. Therefore take/absorb only the essentials, discarding the rest, as a swan takes the milk, discarding the water.

If anyone finds a PDF version of this, please let me know!