Q&A: What are the different types of karma?

More on the middle teaching: Ways to classify karma

Note: These next few articles will be devoted to answering questions asked by readers. If you have questions, please submit them by clicking the button below.

This article addresses two separate, but related, questions:

What is karma?

Need a little detailed explanation about what it is, and how we should work on it.

What are the different types of karma?

In some places I have read about good karma and bad karma, while other places talk about sanchita, prarabdha, etc. Please share some insight on what people mean when they talk about different types of karma.

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Thank you for your questions 🙏🏽

One of the most ancient teachings on the topic of karma can be found in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, from nearly1 3000 years ago:

यथाकारी यथाचारी तथा भवति—साधुकारी साधुर्भवति पापकारी पापो भवति पुण्यः पुण्येन कर्मणा भवति पापः पापेन । अथो खल्वाहुः काममय एवायं पुरुष इति स यथाकामो भवति तत्क्रतुर्भवति यत्क्रतुर्भवति तत्कर्म कुरुते यत्कर्म कुरुते तदभिसंपद्यते ॥YathaaKaaree yathaaChaaree tathaa bhavati - sadhuKaaree sadhurBhavati paapaKaaree paapo bhavati punyah punyena karmanaa bhavati paapah paapena. Atho khalvaAhuh kaamamaya evaAyam purusha iti sa yathaaKaamo bhavati tatKraturBhavati yatKraturBhavati tatKarma kurute yatKarma kurute tadAbhiSampadyateAs it does and acts, so it becomes; by doing good it becomes good, and by doing evil it becomes evil—it becomes virtuous through good acts and vicious through evil acts.

Others, however, say, ‘The self is identified with desire alone. What it desires, it resolves; what it resolves, it works out; and what it works out, it attains.’

- Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 4.4.5

We are nothing more, and nothing less, than our actions. What we consider to be “me” is a bundle of causes and consequences that manifests in the form of thoughts, words, and deeds.

This is karma.

When we classify a person as good or bad, what we are really classifying is the bundle of actions, words, and thoughts that we call “the person.”

If your actions, words, and thoughts are kind, then it is equivalent to saying that you are a kind person. The other way around works too - saying that a person is kind is equivalent to saying that their actions, words, and thoughts are kind.

In this way, what a person does (ie. thinks, says, and does) is what the person is. A “person” is nothing more, and nothing less, than their karma.

To extend this further, thoughts, words, and actions - karma, for short - is constantly changing. I am sitting here one moment, but standing up the next. I am eating one moment, and speaking the next. I am kind in one moment, but unkind the next. Therefore, since karma is not static, and people are nothing but their karma, people are not static.

This can be a revolutionary idea for many of us.

We normally feel like there is some core to us - some “soul” or “essence” that makes me, me.

The idea of karma shows us that this is not true.

We are nothing more than a shifting stream of causes and consequences, generating further consequences. It is this stream that sets us apart from others - karma is what defines a person, and what differentiates one person from another.

By understanding karma in this way, we can start to see people as this constantly shifting stream of their causes, which can never be truly classified into simple categories like “good” and “bad.” As a result, we can build equanimity towards both ourselves and those around us, ceasing judgement, and appreciating the beauty of karma unfolding just as we may appreciate a bird fly, a cloud shift, or a flower grow.

Recap

Over the past three weeks, we have been discussing the particularly complex question of karma in response to the first question listed above. In response to this other readers have also submitted questions, which we will discuss in the next few articles.

If you have any follow up questions around karma, please submit them here so they can be included!

Like much of Indian philosophy, karma is taught at three different levels, depending on the capacity of the listener.

The first, and most basic, teaching is simple - do good, and good will come to you; do bad, and suffering will befall you. This idea is represented by the simple formula shown in the image below:

The key to this teaching is that there is a negative side to positive consequences, and a positive side to negative consequences. When we have pleasant experiences, we are extinguishing our hard-earned punya, or karmic merit, and when we have unpleasant experiences, we can rejoice that our karmic demerit (ie. “bad” karma) is being extinguished.

You can find more on this topic here:

We then began a discussion on the middle teaching.

Here, we first discussed the root of karma - the kleshas, and how avidya - the Primal Ignorance - leads to desire, which then generates action. Our pleasant and unpleasant experiences generate likes and dislikes - we like pleasant things, and dislike unpleasant things.

These likes and dislikes prompt further action - karma - to avoid unpleasant things and experience more pleasant things.

This karma then generates consequences - some good, and some bad - which we classify as “pleasant” or “unpleasant” based on the likes and dislikes from the previous go-around. Heat, for example, is pleasant to a person who lives in a cold region, but is unpleasant to someone who lives in a hot place.

This is one view of the infinite cycle of karma.

More on this topic here:

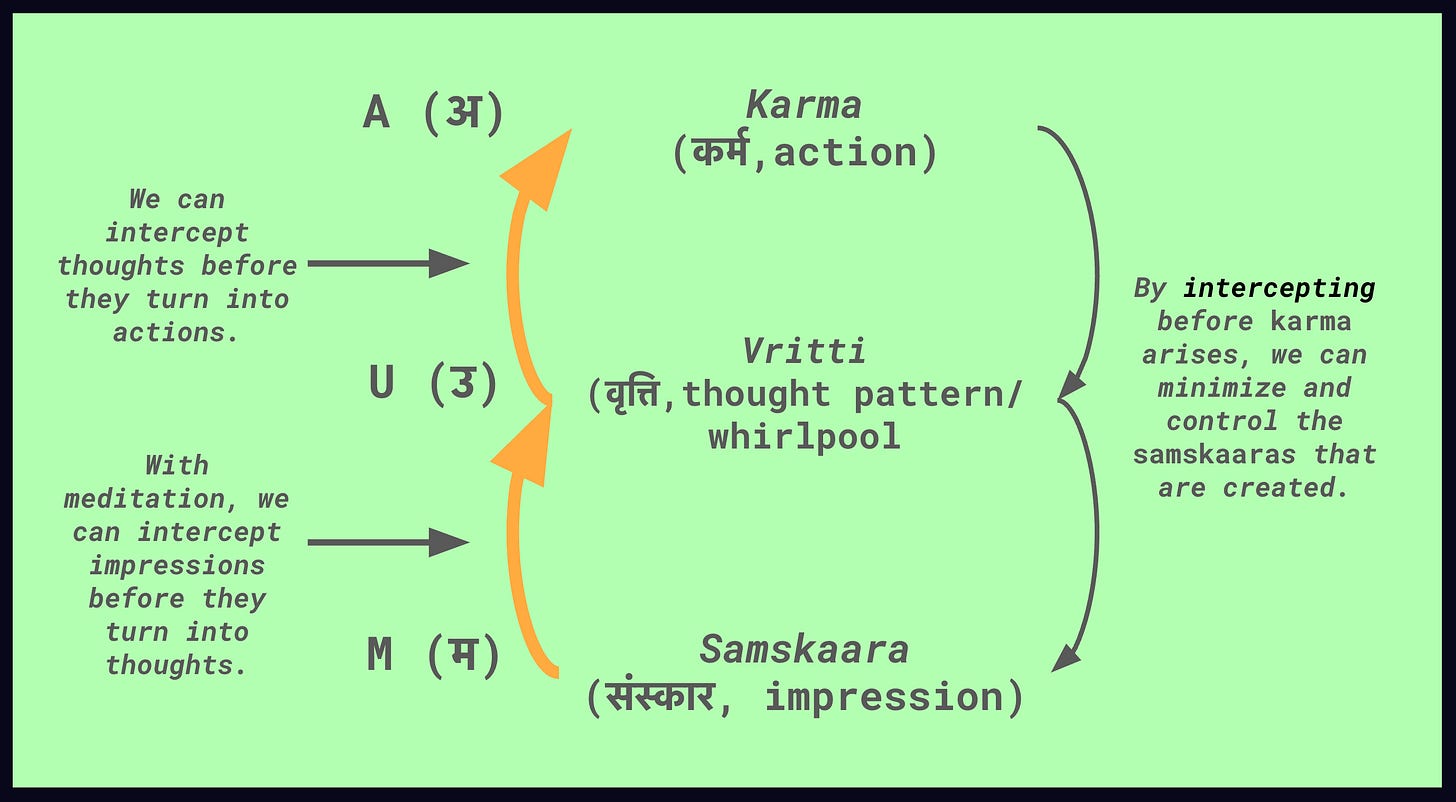

Then, last time, we discussed another angle of the cycle of karma - the wheel of vrittis and samskaaras.

Our actions are experienced in the mind as vrittis, or mental whirlpools. These vrittis leave traces on the mind, known as samskaaras, or impressions. Then, just like a seed, when the conditions are just right, these samskaaras sprout into vrittis, which then bubble up further into actions, starting the cycle anew.

These three levels - the action, the vrittis, and the samskaaras - are represented by ॐ (Om).

A represents the gross world of actions, U represents the suble world of vrittis, and M represents the causal world of samskaaras.

At this level, we can learn to intercept our thoughts before they turn into actions. Further, using meditation as a tool, we can fine-tune our attention to intercept samskaaras before they ever even bubble up as vrittis in the mind.

In this way, we can consciously engineer our karma using Yoga.

More on this topic here:

Today, we will continue the discussion on the middle teaching of karma, diving further into the different types of karma.

Then, in the following articles, we will discuss how karma is stored, the different levels of causation, the mechanisms through which karma is generated and bears fruit, before diving into the highest level of teaching on the topic of karma.

Different types of karma

Karma can be classified in many ways. Most commonly, we hear of “good” and “bad” karma. This classification is on the basis of the perceived quality of the fruit - pleasant or unpleasant circumstances.

However, there are several other ways to classify karma as well:

By the type of samskaara created: Pravritti and Nivritti karma

By the quality of the fruit: Black, white, mixed, and colourless karma

By the timing of fructification: Sanchita, Praarabdha, and Aagaami karma

By the gunas: Sattvic, Rajasic, Tamasic karma

By the presence of desire: Sakaama and Nishkaama karma

By the type of samskaara created

पराञ्चि खानि व्यतृणत्स्वयम्भूस्तस्मात्पराङ्पश्यति नान्तरात्मन् ।कश्चिद्धीरः प्रत्यगात्मानमैक्षदावृत्तचक्शुरमृतत्वमिच्छन्॥Paraanchi khaani vyatrinatSvayambhoosTasmaatParaanPashyati naAntaraAtmanKashchidDheerah pratyagAatmaanamAiskhadAavrittaChakshurAmaritatvamIchhanThe Self-Existent One injured the openings [of the senses, pointing them outwards] - thus external [objects] are experienced, and not the inner Self.

Desiring Immortality, [however], some Patient Ones divert their outward gaze toward the Self within.

- Katha Upanishad, 2.1.1

Karma, as we learned last week, is simply a set of samskaaras, or impressions in the mind. These samskaaras generate vrittis, or mental whirlpools, which we experience as perceptions, imaginations, memories, and other types of thought.

Every time a vritti is experienced, it leaves a trace on the mind. The more it is indulged, and the more frequently it is repeated, the stronger the impression it leaves behind.

These impressions then sprout back into vrittis when the conditions are just right, much like a seed sprouts from the soil when there is enough water, nutrients, and sunlight for it to thrive.

This cycle is known as the vritti-samskaara-chakram, or the wheel of vrittis and samskaaras.

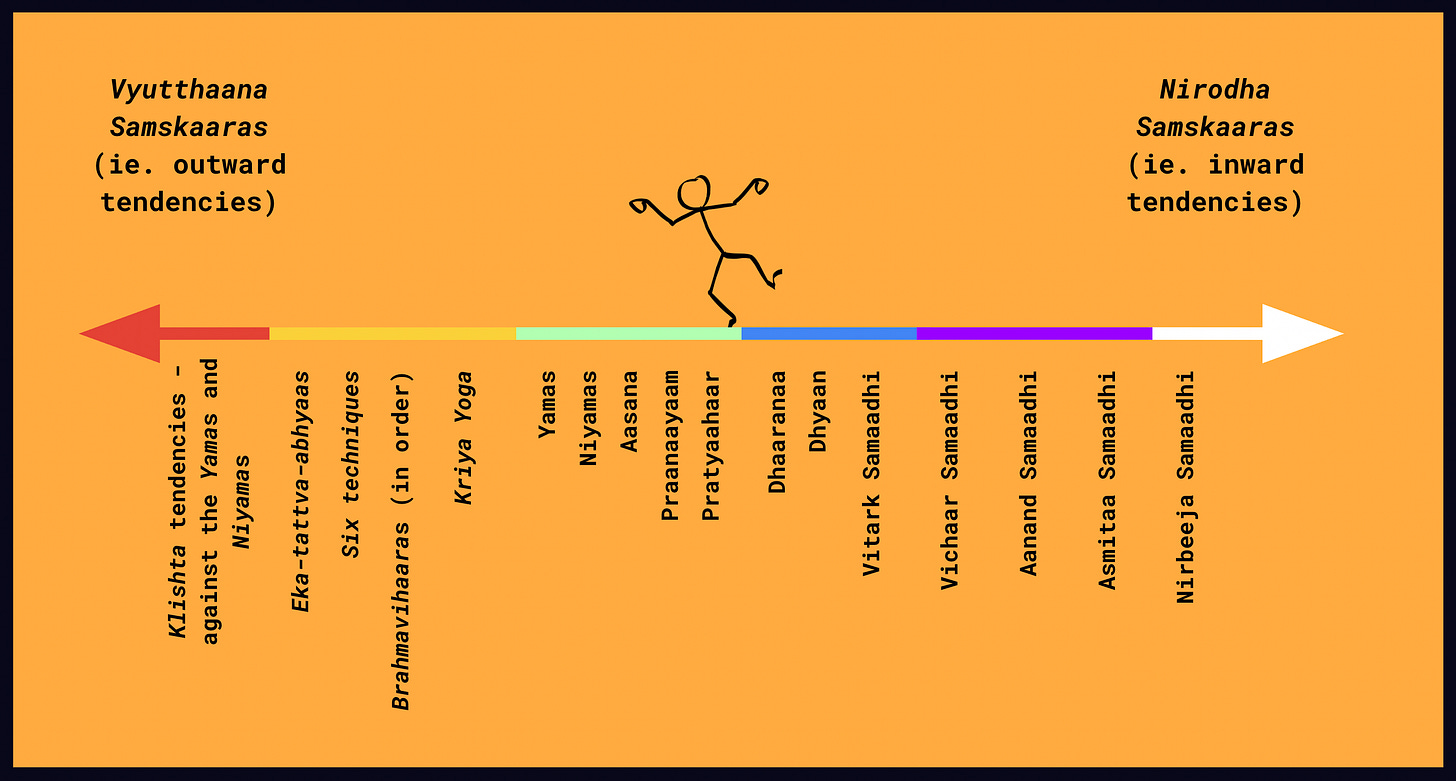

Samskaaras, as we have previously discussed, can be classified into two relative categories, based upon whether they tilt the mind outward, towards the objects of the world, or inward, towards the Self. Outward samskaaras are known as vyutthaana samskaaras (literally gesticulating, or expressive impressions). Inward samskaaras are known as nirodha samskaaras (literally “mastery” impressions).

One method of classifying karma is on the basis of the kind of samskaara it leaves behind in the mind.

Actions that create vyutthaana samskaaras are known as Pravritti Karma (outward, or evolutionary karma). Actions that create nirodha samskaaras are known as Nivritti Karma (inward, or involutionary karma).

These two types of karma are contrary to each other.

बाह्यप्रत्यागात्मप्रवृत्त्योः विरोधात्।BaahyaPratyaagAatmaPravrittyoh virodhaatThe two [types of impressions] are contradictory - those that pull outwards and [those that pull] toward the Self.

- Adi Shankaracharya, commentary on Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.6.1

This very same idea is also expressed in different words in the Christian tradition:

“No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other.

Ye cannot serve God and mammon [ie. greed for wealth, money, or power].”

- Matthew, 6:24

Outward impressions are those which take objects seriously.

If I see a flower, the outward mind immediately categorizes it as a flower, and moves on. If I see a bird, the outward mind immediately categorizes it as a leaf, and moves on. In this way, the outward mind lives in a world of categories, never truly experiencing the world around them. The outward mind does the same thing with people - classifying them quickly, and moving attention to the next thing.

Outward impressions draw attention towards those categories - or objects - which will result in the pursuit of pleasure or avoidance of pain. In this way, the outward mind spends its capacity on names and forms, and so is unable to dive deeper into the underlying reality.

On the other hand, if the person has a preponderance of inward impressions, when they see a flower, they are less likely to categorize it.

Rather, they are more likely to appreciate it just as it is. When they see a bird, they will allow it to be, as it is, without judgement or classification. In this way, the inward mind sees things as they are, without the intervening layer of thought.

What’s more, the inward impressions do not draw attention to one place or another based on likes or dislikes. Rather, they allow the mind to rest where it is, with clarity and peace, noticing the likes and dislikes as they arise and fall.

Outward impressions identify the self with the body-mind, while inward impressions disidentify the Self from the body-mind.

To make this clear, consider the example of a Yogi experiencing a distracting bodily sensation when sitting down for meditation - perhaps a slight itch on their face, or a stiff neck.

In the beginning, when they first sit down, the outward impressions are at their strongest. At this point, the Yogi will likely sit for a few moments, and then their hand will reach up to rub or scratch the itch. If it is a stiff neck, they may stretch out the back or roll the head from side to side. If it is a discomfort in their seat, they may shift slightly or adjust their posture.

These actions - activity of the karmendriyas - is an indication of vyutthaana samskaaras bubbling up in the form of karma.

The more vyutthaana samskaaras there are, the more “restless” the Yogi will feel. This can be easily observed in a room of meditators where there are some people who cannot seem to sit still, even after a long period of time.

On the other hand, if there is a preponderance of nirodha samskaaras, the Yogi will be able to more easily observe the sensations without deploying the karmendriyas to “solve” the problem. They can watch the itch arise and fall, or observe the sensations in the neck or seat with curiosity without giving in to the urge to roll their head or adjust their posture.

This does not mean that a person should suppress their urges. Rather simply that the “giving in” to these urges is an indicator of the type of samskaara in the mind.

Pravritti Karma is that set of actions that generates more vyutthaana samskaaras. That is, giving in to the urge to deploy the karmendriyas is a form of Pravritti Karma.

On the other hand, Nivritti Karma is that set of actions that generates more nirodha samskaaras. In this situation, Nivritti Karma would look like practising observing the sensations without acting on them, to whatever degree is comfortable, and without suppression.

Actions that are motivated by attraction or aversion to sense objects - including everything from physical objects like food and jewellery to subtle objects like thoughts, ideas, and identity - are Pravritti Karma. These actions leave tendencies in the mind which produce a desire to repeat pleasure and avoid pain.

On the other hand, actions that are not motivated by these factors, and which weaken the attachment and aversion to objects, are Nivritti Karma.

P: Is Yoga Pravritti or Nivritti Karma?

Jogi: It depends on the stage of the practitioner. Vyutthaana and Nirodha are themselves relative categories, and so Pravritti and Nivritti are also relative to one another. For example, bar hopping is more Pravritti than staying at one bar the whole night. But going to a bar is more Pravritti than staying at home and reading. Reading itself is more Pravritti than meditation, and so on. In this way, Yoga - specifically Raja Yoga - is more Nivritti than most other activities that one may do, such as eating, drinking, reading, and so on. However, it is more Pravritti than Jnana. Even within Yoga, the Niyamas are more Pravritti than meditation, which is more Pravritti than Samaadhi.

From a practical standpoint, for most people, we can use the Yamas and Niyamas as a framework to classify our own karma into Pravritti and Nivritti. Take a look at the image below - the further to the right your tendencies are, the more Pravritti your karma. The further left, the more Nivritti:

For more on the topic of Vyutthaana and Nirodha Samskaaras, you can take a look at the articles below:

By quality of the fruit

कर्माशुक्लाकृष्णं योगिनस्त्रिविधमइतरेषाम्।karmaAshuklaAkrishnam yoginasTrividhamItareshaamThe Yogi’s karma is not white, nor black. For others, it is threefold.

- Yoga Sutra, 4.7

This classification is perhaps the most widely known and used categorization of karma. Simply said, karma can be good, bad, or mixed - threefold. In Yogic terms, these are known as shukla (white), krishna (black), and shukla-krishna (white-black).

Shukla karma, or “good” karma, is that karma which is done without injury to others. Krishna karma, or “bad” karma, is that karma which results in injury to others.

The fundamental basis for whether karma is considered “bad” or “good” is whether or not it violates the first Yama - ahimsa, or non-violence.

As we know, violence goes far beyond just physically harming another person, extending to our speech, and even our thoughts. What’s more, the other Yamas - truthfulness, non-stealing, non-indulgence, and non-ownership - are simply extensions of ahimsa; examples to demonstrate the subtle manifestations of violence in our day-to-day lives.

For more on the topic of non-violence, you can take a look at the previous article here:

If we think about this simple classification of black and white karma for a moment, we quickly see that there is no physical action that does not involve violence towards other beings.

Even actions that we may otherwise consider to be benign - like breathing, walking, or drinking water - include some form of violence.2

P: How so?

Jogi: When walking, breathing, or drinking water, we are killing microscopic creatures. Besides, even if we try our best to be non-violent, we must still eat. If we eat meat, it is certainly violent, but even when we eat vegetables, we have extended violence towards plants.

P: So just the fact that I continue to live in the body is an act of violence?

Jogi: Yes - individual existence is, in itself, an act of violence. One cannot live in the body without harming other beings. However, we can control the proportion of black or white within our own personal mixture of karma by minimizing violence in our external actions.

In this way, we can see that physical karma - karma played out by the body - is, at best, mixed. There is no physical karma which is entirely shukla, or white.

White karma results in pleasant consequences. Black karma results in unpleasant consequences. Mixed karma results in mixed consequences.

P: Wait a second, there was a fourth kind of karma mentioned in the sutra. It said that the Yogi’s is neither black, nor white, nor mixed. What is the fourth kind of karma?

Jogi: This fourth kind of karma is only known as “karma” from the point of view of an external observer. It is action done without the sense of doership or enjoyership, where the Yogi has surrendered all fruits of, and sees themselves as the Purusha - the Witness of all actions, and the doer of all actions, or no actions at all. In terms of the kleshas, these are the actions that stem from aklishta-vrittis - uncoloured thought patterns.

By the timing of fructification

An ancient example uses the analogy of an archer in the middle of a war.

Imagine that the archer has just shot an arrow. Quickly, they pull a new arrow from the quiver on their back, and place it on their bow, pulling the string towards them. Meanwhile, the quiver carries a very large number of arrows, waiting to be shot when the time is right.

In the analogy, there are three categories of arrows:

The arrows in the quiver, waiting to be shot

The arrow on the bow, which is presently in the process of being shot.

The arrow which was just let go, which may or may not have hit the intended target.

These three categories of arrow can be compared to the three categories of karma, classified by the timing of fructification:

Sanchita karma: Stored karma

Aagaami karma (aka kriyamaana karma, or vartamaana karma)3: Present actions

Praarabdha karma: Ripe karma, running on momentum

Sanchita karma: Accumulated karma

In the example of the archer, sanchita karma is analogous to the arrows in the archer’s quiver which have not yet been shot.

Sanchita karma is that karma which is accumulated from all actions done by an individual. Specifically, these are tendencies - samskaaras - that have not yet borne fruit.

P: How can I know my sanchita karma?

The tendencies that you manifest are your sanchita karma in action.

If you have a preponderance towards music, art, math, or even more mundane likes and dislikes towards things like brussels sprouts, Hawaiian Pizza, or white chocolate, this is your sanchita karma.

However, not all sanchita karma manifests itself. It only shows up when the conditions are just right. This subset is known as praarabdha karma, discussed below.

For example, you may not realize that you like white chocolate until you try it for the first time. If we consider it, this liking for the taste of white chocolate is not new. It always existed - perhaps in a slightly different form, or perhaps as a combination of other sanskaaras - somewhere in the recesses of the mind, and took the opportunity to manifest itself when your taste buds touched the white chocolate.

P: How do you know it’s not new?

Jogi: Because all effects - in this case likes and dislikes - are the result of past causes of the same class. A mango seed cannot create a mango tree.

This is also true for bigger things like occupations, hobbies, personality traits, and even relationships with other people.

A person may not know that they had a trait of anger until they suddenly came into a difficult financial or social situation. Another person may not know that they were particularly talented at pottery until they took a pottery class later in life.

Sanchita karma is like the quiver of arrows, waiting to be shot when they get picked up, but patiently sitting dormant until the time is right. Meditation, as well as a close observation of your actions, your words, and your mind, can give you a good idea of your sanchita karma.

Praarabdha karma: “Already started” karma

Praarabdha karma (literally “already started” karma) is a special subset of sanchita karma which is fructifying right now.

In the example of the archer, praarabdha karma is analogous to the arrow which has already been shot, and is flying through the air on its own momentum.

This arrow cannot be pulled back by the archer, no matter how hard they try. Nor can its course be controlled - if a gust of wind comes and takes it off track, or if an unintended target comes in the way of the arrow’s path, there is nothing that the archer can do about it.

Said another way, praarabdha karma is that subset of sanchita karma which finds the right conditions to sprout in this life, between the moment of birth and the moment of death.

Traditionally, praarabdha karma is compared to the momentum of a potters wheel which continues to spin even once the potter has moved away. Another traditional example compares praarabdha karma to fruit on a tree which falls to the ground naturally once it has become ripe. More modern analogies include a fan which continues to spin even after it has been switched off, or a car which continues to roll forward even though the driver’s foot is no longer on the accelerator.

The various actions that we do set certain consequences in motion. Some of these causal chains are more easily visible to us than others. Often, we may suffer from great anxiety trying to adjust outcomes the action has already been done. In these cases, our remedies - if any - necessarily involve further action, using new actions to offset the previous consequence.

This is like an archer firing a second arrow to hit the first arrow in order to get it back on target. Very difficult. It is far easier to aim carefully before shooting the arrow in the first place.

As an aside, praarabdha karma is a topic of great discussion and debate amongst various schools of Indian philosophy when it comes to the topic of jivanmukti, or “Freedom while Living”.

Specifically, while other categories of karma can be destroyed or adjusted, praarabdha karma cannot be extinguished or destroyed no matter what kinds of practices a person does. It is the momentum which keeps the body alive, which keeps the person acting as they are, and results in the type of birth, lifespan, and life experience of the individual.

P: Ok, I understand that I can’t remove or adjust by praarabdha karma. But can I add to it?

Jogi: Yes, you can (and most likely) already are. However, you cannot choose whether your new karma will lie dormant in sanchita or come to fruition in this life as praarabdha. This category of “newly generated karma” is called Aagaami Karma.

Aagaami karma: Present/approaching karma

The third and final category of karma is aagaami (literally “approaching”) karma, also known as vartamaana (ie. present) karma, or kriyamaana (ie. “being done”).

In the example of the archer, aagaami karma is the arrow that is currently in the bow and is about to be shot.

Where Praarabdha is already playing out, and Sanchita is lying dormant, Aagaami Karma is - at this level - entirely within our control. We can decide what to do next, exercising our free will4 to adjust the consequences that we will reap in the future.

The effort required for Yoga comes under this category. You certainly have some praarabdha karma that has led you this far, but it is up to you to pick it up and practice.

These new actions fall into two categories:

Those that are in line with our existing samskaaras

Those which generate new samskaaras in the mind

We can easily distinguish these by noticing which actions which feel easy and natural, and which actions feel more difficult.

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa used to give an example of a boatman on the riverside. At the beginning of a boat ride, the boatman needs to use a long stick to push against the bank with great strength. Then, they need to use an oar to vigorously paddle into the current. Eventually, the boat reaches the middle of the river, where the current is strong, and so the boatman can sit back and smoke their pipe as the current carrie the boat along.

When we try to create a new habit (ie. generate new karma), at first, it can be quite difficult. The reason for this is that we are trying to move upstream, against our current tendencies - our sanchita karma. Eventually, however, with time and practice, it becomes easier and easier, until finally it starts to feel natural. At this point, we can trust that the habit will continue without any special effort, just like the boatman sitting back when he realizes that the boat can float along in the current.

On the other hand, we often act along the lines of our current conditioning.

For example, if a person is prone to anger, it does not take any special effort for them to lose their temper - it just happens. However, it will take significant effort - at least initially - for such a person to stay calm in a situation where they would normally have gotten angry.

In this example, the tendency towards anger is praarabdha karma, that is bubbling up in the form of a vritti in the mind. At this point the person has a choice. They can either follow the tendency towards anger and shout, jump up and down, etc, or they can take a deep breath and cool down. In either case, the action that they decide to do is their aagaami karma. The only difference is that one is in line with their existing tendencies, while the other - while more difficult - is a step towards consciously adjusting their karma.

Aagaami karma is perhaps the most critical to grasp. Our existing storehouse of karma is vast, and may or may not come to fruition immediately. Our praarabdha karma is running on its own momentum, and is coming no matter what.

However, our aagaami karma is where we have the agency to change our existing habit patterns, and adjust them in ways that we want rather than following old patterns.

If we want to be less angry, we can generate samskaaras that go against anger through our actions in the present moment. If we want to meditate, we can decide to practice in the present moment. If we want to become truthful, we can decide to tell the truth in the present moment.

The key to adjusting our karma using our aagaami is to remain constantly mindful of our thoughts, words, and actions - every thought that arises, every word we say, and everything we do leaves an impression. Every moment counts.

Having said this, our aagaami karma is also the reason why it is impossible to exhaust our storehouse of karma, even in a million lifetimes. While we are playing out our stored (sanchita) karma, we are also acting right now. Every action we do leaves an additional impression, leaving us in an infinite cycle.

P: Is there a way out?

Jogi: Yes - this is precisely what the four Yogas are for!

Two other classifications: Based on the gunas and based on desire

In addition to these three, we can also classify karma on the basis of the gunas.

कर्मण: सुकृतस्याहु: सात्त्विकं निर्मलं फलम्।रजसस्तु फलं दु:खमज्ञानं तमस: फलम्॥सत्त्वात्सञ्जायते ज्ञानं रजसो लोभ एव च।प्रमादमोहौ तमसो भवतोऽज्ञानमेव च॥Karmanah sukritasyaAhuh sattvikam nirmalam phalam RajasTu phalam dukkhamAjnaanam tamasah phalamSattvaatSamjaayate jnaanam rajaso lobha eva cha PramaadaMohau tamaso bhavatoAjnaanameva chaSattvic actions produce resplendent/serene fruits. Rajasic actions produce dukkha as their fruit. Tamasic actions produce ignorance as their fruit.

From [actions born of] sattva, knowledge arises. From [actions born of] rajas, greed [arises]. From [actions born of] tamas, ignorance and delusion [arise].

- Bhagavad Gita 14.16-17

Sattvic karma is that set of actions which leave behind a feeling of calmness, lucidity, and upliftment in the mind. Rajasic karma is that set of actions which leave behind feelings of agitation, desire, and passion in the mind. Tamasic karma is that set of actions which leave behind feelings of delusion and darkness, leaving behind tendencies that violate the Yamas in thought, word, and deed.

Finally, the simplest classification of karma is on the basis of desire. Sakaam karma is that set of actions done with desire, while nishkaam karma is that set of actions done without any desire.

P: Wait a second, doesn’t all action stem from desire?

Jogi: Absolutely correct! All action, no matter how small, stems from desire. Avidya → Kaam → Karma.

P: So then what is nishkaam karma?

Jogi: This is a good line of inquiry. We will pick this up as we discuss the final teaching.

TL;DR

Karma can be classified in many ways.

First, we can classify karma on the basis of the kind of impression that the action creates - inward, or outward.

Inward impressions (nirodha samskaaras) are helpful to Yoga, while outward impressions (vyutthaana samskaaras) are counterproductive to Yoga. Actions that generate inward impressions are classified as Nivritti Karma (literally involutionary karma), while actions that generate outward impressions are classified as Pravritti Karma (literally evolutionary impressions).

Second, we can classify karma on the basis of the quality of fruit.

This is the most common classification in popular culture, commonly communicated as “good” and “bad” karma. In Yoga, this classification is threefold - “white” karma, “black” karma, and “mixed” karma. White (ie. shukla) karma is that action which does not result in harm to others, and so results in sukha, or pleasant results. Black (ie. krishna) karma is that karma which harms others, and so yields unpleasant results. Mixed (ie. shukla-krishna) karma is that which yields mixed results. Investigating this, we find that any physical action is, at best, mixed.

Third, we can classify karma on the basis of how it fructifies.

Sanchita karma is like the storehouse - the quiver in which all the arrows lie dormant. Praarabdha karma is a subset of sanchita karma - those arrows which have already been shot, and are now running on their own momentum, generating our current life experiences, this very moment. Finally, aagaami karma, also known as vartamaan karma or kriyaamaan karma is that set of actions which you are doing in the present moment. This aagaami karma generates future consequences by way of the storehouse of sanchita karma, trapping the individual in an infinite cycle of doing actions and having to experience their fruits.

Finally, we went over two other methods to classify karma - based on the gunas, and based on desire.

Next time, we will continue the discussion on the middle teaching.

Until then, if you have any additional questions, please submit them by clicking the button below!

The dating here is a topic of debate, with many Indian scholars arguing that this Upanishad is far older.

In the Jain tradition, which has taken this idea to its logical culmination, a person who sees this truth and voluntarily starves themselves, is considered a Mahavira - a great hero.

In Yoga, this is not necessarily required.

Some teachers split these out, where aagaami karma refers to karma which has not yet happened (ie. future actions), and vartamaana or kriyamaana karma refers to action that is taking place in the present moment.

More accurately, the feeling of free will, at the level where we assume the buddhi to be “self” rather than non-self, under the influence of avidya.