Q&A: What is Karma? Part I

The Basic Teaching

Note: These next few articles will be devoted to answering questions asked by readers. If you have questions, please submit them by clicking the button below.What is karma?

Need a little detailed explanation about what it is, and how we should work on it.

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Thank you for your question 🙏🏽

The word “karma” nowadays carries a lot of baggage.

One common imagination is of some sort of heavenly bank account - the more good things we do, the more credit we accrue, and our bad actions are marks against us.

This is related to another popular imagination of karma - one of a sort of cosmic retribution or divine judgment. The idea here is that if we do good things, good things will happen to us, and if we do bad things, the Universe (or God) will somehow make us pay.

Finally, a third popular imagination links karma with fate, predetermination, or destiny. Here, the idea is that we simply play what is “written”, and have no say in the matter of what happens in our lives.

These ideas are not entirely wrong, but the problem is that they create a magical view of karma, viewing it as a matter of belief, veiled in mystery, rather than seeing it as a practical reality.

Having said this, the importance of learning about karma is not in understanding the specifics of understanding how it works, but rather in seeing how we are trapped by it so that we can search for a way out. Said another way, the goal is not to establish karma, but to escape it.

In Yoga and Vedanta (as well as other schools of Indian philosophy), students are divided into three classes, based on their current abilities:

Kanishta Adhikaari: The “Youngest” aspirant

Madhyama Adhikaari: The “Middle” aspirant

Uttama Adhikaari: The “Highest” aspirant

Each type of student is given a specific type of teaching.

If a student is given a teaching at a different level from where they currently are, it does not stick. That is, the teaching is either confusing, or seen as superstition, and in either case does not leave an impression in the mind.

Karma - like all of Indian philosophy - is taught in three different ways to each of these types of students.

For the kanishta adhikaari, karma is taught simplistically, as essentially a cosmic bank account or credit score, where individuals gain merit or demerit based on their actions. It is also taught through stories such as those found in the Puranas, the Mahabharat, or the Ramayana, and the goal is to drive home the idea of “do good and good will come to you.” This is the basic teaching.

P: But in my experience, it’s not always this simple. Bad things happen to people who do good, and good things happen to people who do bad. How can we reconcile this?

Jogi: Yes. There is no denying that this is how we experience the world. As a result, the basic teaching does not hold up to scrutiny, especially within the worldview of a single lifetime. To address questions like this, there are two deeper levels of teaching.

For the madhyama adhikaari, karma is further broken down into the various types of karma, based on when action will bear fruit. This is the most complex teaching. In terms of how to act on karma, aspirants are taught to devote all their actions to Ishvara, or to let go of attachment to the fruits of actions so as to break free from karma.

You can read this article for more on the topic:

Notice, the goal here is no longer to simply “do good”, but rather to break free of karma altogether. This is the middle teaching.

Finally, for the uttama adhikaari, the very root of karma is investigated. The root is seen to be desire, which is further rooted in avidya (the Primal Ignorance).

Furthermore, it is seen that in Truth, there is no karma at all. Said another way, karma is dissolved, or sublated, through Knowledge of Self in the same way that a mirage is sublated by walking closer to it, or an illusory snake is sublated by turning the light on to see that it was a rope all along. This is the higher teaching.

Given that this is a complex question, we will spend a few articles discussing it. In this and the following articles, we will discuss all of these concepts in some detail.

What is karma?

The word “karma” is derived from the root kr (कृ), which - in this context - means “to do.” Literally, it simply means “action.”

The idea of karma is one of the few concepts shared by all of the Indic schools of philosophy (with the exception of the Chaarvaak), and specifically refers to the fact that all of our actions have consequences, which result in further consequences, ad infinitum. Karma refers to not only the actions that we do, but also their results - both mental and physical.

Said another way, karma is the principle of cause and effect, applied to our actions, words, and thoughts.

That is, our actions, words, and thoughts are nothing but effects of past causes, and are, simultaneously, the causes of future effects.

In this way, karma is a beginningless cycle. All effects have past causes, which in turn have their causes, and so on.

While the Indic schools of philosophy (e.g. Vedanta, Yoga, Mimamsa, Sankhya, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, etc.) have philosophically developed the idea of karma to a significant degree, the underlying concept is not unique to Indic schools of philosophy. Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and various other traditions all have some conception of the same idea, only through different frameworks or lenses.

For example, the ideas of morality, sin, heaven and hell, divine judgement, purity of mind, and even the principle of Jesus’ crucifixion are all essentially rooted in various conceptions of karma.

“Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.”

- Galatians 6:7

The Basic Teaching

At the most fundamental level, karma can be seen as a causal connection between an action and its result. This is formulated as follows:

Dharma → Punya → Sukha

Adharma → Paap → Dukkha

That is, by doing “good” things, the individual gains karmic merit, called punya. This punya results in pleasant experiences, known as sukha.

On the other hand, by doing “bad” things (aka adharma), an individual gains karmic demerit, called paap. The word “paap” has come to mean “sin” in many Indian languages, however, here, it refers not to the action itself, but to the demerit accumulated as a result of the action. This paap results in unpleasant experiences, known as dukkha.

This is the most basic framework for how karma works. It seems straightforward, but there is a secret here hiding in plain sight.

Normally, when we have a pleasant experience, we view it as a good thing, and when we have an unpleasant experience, we view it as a bad thing.

However, the framework of karma flips this basic idea on its head.

That is, when we have a pleasant experience, we are extinguishing our hard-earned punya. In this way, unpleasant experiences are actually good news - we somehow, by a stroke of luck, have the opportunity to extinguish our paap.

The following story illustrates the point:

Once upon a time, there was a violent king who had a great disregard for wandering monks. In his mind, all monks were simply lazy fools who roamed the land because they did not want to work. He did not have any regard for their wisdom or their teachings, and believed all wandering monks to be charlatans.

One day, the king was standing in his balcony, eating a banana. As he took his final bite, he nonchalantly tossed the peel into the street below. Suddenly, he heard a cry of delight!

He looked down, and saw that a wandering monk had gleefully picked up the banana peel and started to try and eat it.

Enraged, the king ordered his servants to pick up the wandering monk and torture him. Since the monk’s gleeful cries had fallen upon the king’s ears, the king ordered his servants to slowly drive a hot rod into the monk’s ears, as retribution.

The servants tied the smiling monk down to a table, heated up the rod, and slowly began to insert it into the monk’s right ear. As they did this, the monk began to laugh and exclaim at his good fortune.

Confused, the servants pulled the rod out from his ear, at which point the monk suddenly burst into tears, as though saddened by the turn of events.

Then, again, they inserted the rod, and he began to laugh. They removed the rod, and he began to cry.

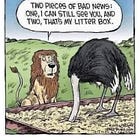

Noticing this pattern, the king ordered his servants to stop, and asked the monk what was going on, “Why are you laughing when you are being tortured, but crying when the torture stops? Are you crazy? You should be crying when you are being tortured, and happy when you are not! What is wrong with you?”

The monk responded, “When I am in pain, it is a great joy, for my bad karma is being burned. The more I suffer, the more the karma burns. I spend months in meditation in mountain caves trying to burn my karma, and here it is happening within seconds. What good fortune!

“On the other hand, when the torture stops, I have a moment to think about other things. I think about the pain I am experiencing for simply eating the peel of the banana, and weep out of concern for the suffering that will be experienced by the person who ate the banana itself. If this is the consequence for eating the peel, what must be the consequence for eating the fruit!”

Seeing the wisdom in his words, and overcome with the overflowing compassion of the monk, the king fell to his knees, and begged for forgiveness.

This point of view helps us to establish ourselves in upeksha, or equanimity - the fourth and most elusive of the Brahmavihaaras.

Established in equanimity, we no longer lament our suffering, and can easily avoid arrogance when we have good fortune. We can remain steady in all circumstances, and can ensure a calm mind regardless of what is going on in the world around us.

So at this level, how should I work on my karma?

At this level, the first step is to build up good karma1 and burn down bad karma. Normally, it can be a tremendous burden on the mind to continuously consider what is good versus bad karma. Yoga simplifies this tremendously with the first two limbs - the Yamas and the Niyamas. The Yamas are an especially useful framework when it comes to building up good karma.

However, keep in mind that the ultimate goal is not to build up good karma, but to break free of all karma - including good karma.

P: Huh? How do I do that?

We will discuss this topic further in the next couple of articles.

What’s next?

For many of us, this teaching is sufficient. However, for others, it is not nearly enough.

We may wonder, for example, what is the mechanism by which karma fructifies? What kinds of actions lead to particular kinds of results? How do we know the difference between a “good” action and a “bad” action? Are there different types of karma? How do we change our karma? What about reincarnation, how is that related to karma?

Next time, we will explore these questions as we go over Middle Teaching - the way of understanding karma for the madhyama adhikaari.

If this sparked any additional questions, please submit your questions here, by clicking the green button below:

Next time: Karma: The Middle Teaching

More correctly, one does not build up good karma, but rather uses good karma to build up punya.