The Turning Point

The final ascent to Kaivalyam: Part I

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

तत्रात्मभावभावनाकोऽहमासं कथमहमासम् किंस्विदिदं कथंस्विदिदं के वा भविष्यामः कथं भविष्याम इति।There [in the mind of the to-be Yogi], thoughts about the nature of the Self appear as “Who was I?”, “How was I?”, “What is this?”, “How is this?”, “What will we become?”, “How will we become?”.

- Vyasabhashyam on Yoga Sutra, 4.25

Not everyone is curious about the big questions.

For most of us, the pleasure and suffering of the world is more than enough to deal with. Even for those of us who are initially curious, many are satisfied with a verbal response, taking it on faith, and moving on with their lives.

There is no fault in this.

For a few, however, this curiosity is more than just curiosity. It is a burning need. For this group, it is not enough to be told by someone, or even to logically understand. Here, every question seems to bring more questions, but these few do not give up. They must see for themselves, no matter the cost.

In Yoga psychology, the tendency towards this kind of burning curiosity to understand the nature of reality is due to a preponderance of nirodha samskaaras (inward tendencies) in the mind. The proportion of nirodha to vyutthaana (outward) samskaaras changes continuously, and so it is not a “personality trait” or any such thing.

Rather, it is simply a matter of fact for a particular mind at a particular slice of time.

On the other hand, for those who are willing to let these questions go and return to their lives, or those for whom these questions do not arise at all, it is due to a preponderance of outward, or vyutthaana samskaaras. It is this same latter group who will initially find it difficult to sit still or meditate.1

The process of Yoga can be framed as a systematic method to calm the mind and tilt it inwards - to increase the proportion of nirodha samskaaras and reduce the proportion of vyutthaana samskaaras.

The mind, and so all of Prakriti, has only two purposes - bhoga (experience) and apavarga (liberation).

Vyutthaana samskaaras lead to bhoga, while nirodha samskaaras lead to apavarga.

Said another way, the more vyutthaana samskaaras one has, the more dukkha they will experience, because all bhoga - even when it feels pleasurable - ultimately leads to dukkha - like honey mixed with poison.

Given this, it seems like the obvious choice - increase the proportion of nirodha samskaaras, and be happy.

However, we don’t usually think in this way.

We have been conditioned throughout our lives (and perhaps before that as well), to seek fulfilment through experience. We were taught even as children to find jobs that we enjoyed (literally, bhoga), or to make money, become powerful, and so on. Throughout our lives we have been bombarded with bhoga - advertisements, social media, TV shows, movies, music, and so on.2

To make matters worse, this tendency is also self-propagating - the people around us, also conditioned in this way, will talk about their bhoga - the places they went, the things they did, and so on (a la “what did you do this weekend?”).

For those of us with a higher degree of vyutthaana samskaaras, this can make us feel like we need to reciprocate by sharing our own bhoga with them. This vicious cycle can leave everyone involved feeling unfulfilled, like they must have more in order to be happy - more money, more power, more things, more experiences, more ideas, etc. - thus tilting the mind further outward, and so making it more unhappy.

Vyutthaana samskaaras beget more vyutthaana samskaaras.

नास्ति बुद्धिरयुक्तस्य न चायुक्तस्य भावना।न चाभावयत: शान्तिरशान्तस्य कुत: सुखम्॥nāsti buddhir-ayuktasya na chāyuktasya bhāvanāna chābhāvayataḥ śhāntir aśhāntasya kutaḥ sukhamFor the one without a steady mind, there is neither reasoning (ie. about the Self), nor meditation. Without meditation, there can be no peace, and without peace, how can there be happiness?3

- Bhagavad Gita, 2.66

The more vyutthaana samskaaras there are, the less likely a person is to have the intense curiosity to answer the big questions. The less intensely one feels this burning need, the slower progress in Yoga will be.

On the other hand, the more nirodha samskaaras there are, the more likely it is that they will have this burning curiosity. The more intense the curiosity, the more intensely they will practice, and so the quicker their progress will be.

More on the levels of practice here.

Over the past few weeks, we have been going over the traditional fourfold method used by doctors to communicate with their patients:

Rogah: The Diagnosis

Hetuh: The Etiology, or the Cause

Aarogyam: The Prognosis

Bhaishajyam: The Treatment

The diagnosis, we found, is dukkha - the up and down nature of life, like a bumpy ride. This is not “suffering” as such, but rather the constant feeling of incompleteness, dissatisfaction, and imperfection which permeates every part of life - even the parts that seem pleasant.

The cause of dukkha is the conjunction between the Seer and the Seen. This manifests as a confusion about the meaning of the word “me” - sometimes we refer to the body as “me”, sometimes the mind, sometimes some combination. Other times, we refer to the body and mind as a possession. Upon some analysis, however, we find that neither am I the body, nor am I the mind, and nor are they my possessions.

This conjunction, we found is further caused by avidya - the Primal Ignorance, and the final root of all suffering, which has no further cause.

We then discussed the prognosis - it’s good news. I am the Purusha, the eternal Witness of all the change, untouched by all dukkha. The Self is free - always was, and always will be.

This freedom appears in the form of a sevenfold insight, which we discussed over the past two weeks. These are not seven separate insights, but rather seven aspects of the same, single Insight.

The first of these seven aspects is that all questions disappear.

This is a key point of accelerated progress - a trigger that results in the mind tilting towards Kaivalyam.

All doubts are destroyed

भिद्यते हृदयग्रन्थिश्छिद्यन्ते सर्वसंशयाः। क्षीयन्ते चास्य कर्माणि तस्मिन्दृष्टे परावरे॥Bhidyate hrdayaGranthishChhidyante sarvaSamshayaahKsheeyante chaAsya karmaani tasminDrshte paraAvareThe knot of the heart is untied, all doubts are destroyed, and karma wanes when the One who is both above and below (ie. the Self) is Seen.

- Mundaka Upanishad, 2.2.8

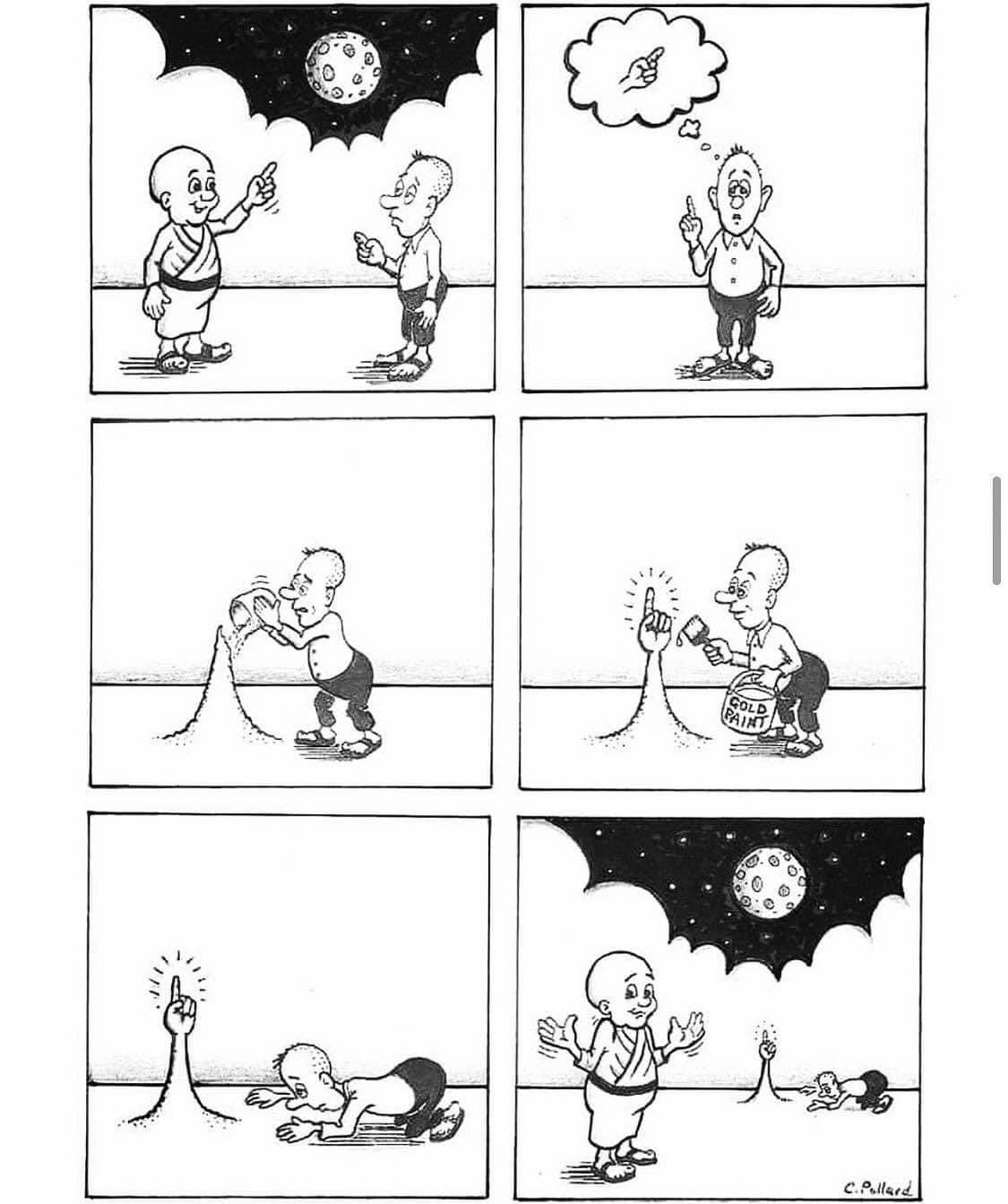

Normally, when we ask a question, we expect an answer in terms of symbols.

P: What do you mean?

Jogi: Words - whether written or spoken - are symbols. Pointing is a symbol, thoughts are symbols, and so on. Anything which points to another thing is a symbol.

Symbols are pointers - not the actual thing. “Ring ring” is not the same as the sound of a phone ringing, “oink” is not the sound of a pig, and, to quote Alan Watts, “The menu is not the meal.”

We use words to generate thoughts, which are also symbols. In this way, we use symbols to generate other symbols or point at further symbols, and so live in a world full of symbols, missing out on the real thing.

However, despite its shortcomings, this is what we usually call “knowledge.”

In Yogic epistemology, knowledge can be gained in three ways:

Pratyaksha: Direct perception

Anumaana: Inference

Aagama: Trusted testimony

The latter two are dependent on the first. That is, in order to infer something, you must directly perceive something else (e.g. you must directly see smoke to infer fire); in order to learn something from trusted testimony you must also perceive something else (e.g. you must directly perceive the book you are reading or the words of the teacher).

Normally, all knowledge gained through these three methods is mixed in with words and ideas as discussed in the article below:

However, in Nirvitarka Samaadhi, we get our first glimpse of what knowledge can be like without the curtain of thought - known as aparapratyaksha, or the higher perception.

At the final stages of Samaadhi, this higher perception can be applied to the chidaabhaasa - the Reflected Consciousness, or Phantom Consciousness, reflected in the sattvic aspect of the buddhi. Said another way, we notice - using this new tool of aparapratyaksha - that the awareness we thought was the subtlest, finest aspect of “me”, is in fact also an object to Me.

विशेषदर्शिन आत्मभावभावनाविनिवृत्तिः।For one who sees the distinction (between mind and Self), reflecting on the nature of the self ceases.

- Yoga Sutra, 4.25

In this way, it is directly seen - without the interference of thought - that the Self is different from not only the body, but from even the most subtle aspects of the mind. There is, therefore, no longer any identification with the mind, body, or any combination thereof.

What’s more, the entire projection - this Universe - is seen to be something like a light show. A giant Rorschach plot of individual, momentary perceptions, rising and falling, with no particular direction, story, or meaning.

It is like a spontaneous, ecstatic dance, or like the sound of a babbling baby.

When we see this directly, all questions - which are just combinations of symbols - are seen to be just like the rest of the Dance. They are patterns of movement upon which the mind superimposes meaning with additional patterns of movement, in a recursive spiral of meaning-making.

“I don’t see any question there. You already have the answer. You think that you have questions, you don’t have any question! I don’t see any questions … no further conversation necessary.

All that is coming out of me is the barking of a dog - nothing else. You are the one that is … turning this barking into a language ... You are taught how to space this barking that has come out of this individual … I cannot be of any help. Try somebody else. Good luck to you.”

- UG Krishnamurti

The questions help to drive us to Yoga, and keep us motivated to stay on the path. At the end, however, the answer is not in the same format that we expect. We expect an answer in terms of additional symbols, but instead we see that our questions themselves are simply symbolic, and that symbols themselves are symbolic.

Instead, the answer is a direct flash of Insight - a moment of recognition that all we are doing, and taking ever so seriously, is just like a bird chirping or a dog barking.

The turning point

तदा विवेकनिम्नं कैवल्यप्राग्भारं चित्तम्।Then, the mind, tilted towards viveka [begins to] gravitate towards Kaivalyam.

- Yoga Sutra, 2.26

This initial insight initially comes as a glimpse, and disappears shortly thereafter, but is a significant turning point. The mind, clearly seeing that it is different from the Self, starts to shed its conditioning of vyutthaana samskaaras, and take up more and more nirodha samskaaras.

P: I have felt this shift in myself. Does this happen earlier on in Yoga too?

Jogi: Yes, it begins very early on. The more nirodha samskaaras there are, the less the individual is interested in the external world. They become disinterested in sense gratification, in wealth, power, and signalling virtue to others (ie. kaam, artha, dharma), although they may physically continue in the same activities as before.

P: How is this different?

Jogi: Now, the primary focus of life has become Moksha, or Kaivalyam - to the exclusion of all else. Initially, there are still residual samskaaras that pull the mind back into the world of sense objects. Now, the goal has become clear, since it has been directly seen. As a result, there is no going back - the seesaw has tilted in the direction of Kaivalyam, and the mind automatically gravitates towards Freedom without any explicit effort. Unlike previously, where it takes significant will-power and mental effort, here, Yoga becomes automatic, like a rock rolling downhill.

However, the journey from here to final Kaivalyam has its own challenges, in the form of residual karma. This will be the topic of our discussion next time.

Next time: Breaks in Kaivalyam

If you fall into this group, start here and click “next” at the bottom of the page to progress systematically:

These things by themselves are not bad. It is rather that the outwardly inclined mind is easily drawn to these objects due to past conditioning, and following a particular conditioning strengthens it further. For more on this topic, take a look at the articles on Pratyaahaar - the often forgotten fifth limb of Yoga starting here:

This is a Yogic interpretation of the verse, as you will find with many translations in this newsletter. The same verse is interpreted by bhakti (devotional) schools translating the word “yukta” as attachment to God.