The Cause: The Conjunction between the Seer and the Seen

Moksha, Kaivalyam, Enlightenment: Part II

If you have recently signed up for this newsletter, welcome! If you would like to begin systematically, you can start with the article linked here and continue by clicking the “next” button on the bottom right of each post:

Alternatively (or additionally), you can click the links to previous articles (within the article) for additional context on certain concepts.

Finally, if you would like some guidance on where to begin, on a particular topic, or if you have a question you would like answered, you can submit your questions by clicking the button below.

All questions are welcome, and some may even be featured in future articles.

🙏🏽

Kunal

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Last week, we began a discussion on the fourfold method used by doctors in ancient India to communicate with their patients:

Rogah (रोगः): The Diagnosis

Hetuh (हेतुः): The Etiology, or the Cause

Aarogyam (आरोग्यं): The Prognosis

Bhaishajyam (भैषज्यं): The Treatment

Specifically, we discussed the diagnosis of our current state - dukkha (suffering, incompleteness, frustration, insufficiency) - and the various ways in which it manifests. You can find the article here:

Today, we will discuss the cause of dukkha - the apparent conjunction between the Seer and the Seen.

The Cause: Samyogah

द्रष्ट्रदृश्ययोः संयोगे हेयहेतुः।DrashtriDrishyayoh samyoge heyaHetuhThe conjunction (ie. Samyogah) between the Seer and the Seen is the cause [of suffering] to be avoided.

- Yoga Sutra, 2.17

What are the Seer and the Seen?

Jogi: Just common sense - no fancy philosophy. Are your eyes looking at these words, or are these words looking at your eyes?

P: My eyes are looking at the words.

Jogi: Look at your hand. Are your eyes watching your hand, or is your hand watching your eyes?

P: My eyes are looking at my hand.

Jogi: Who sees the eyes? Is your mind the observer of your eyes, or are the eyes observing your mind?

P: My mind is observing my eyes - it knows when they are open, closed, tired, stinging, clear, or blurry.

Jogi: Great. But who watches the mind? Are you observing your mind, or is your mind observing you?

P: Wait, what do you mean? Am I not my mind?

Jogi: Who knows when the mind is active, or when it is dull? Who knows when it is focused, or when it is scattered?

P: The mind itself, no?

Jogi: That is introspection - who is aware of the mind when you are not introspecting? Is a surgeon introspecting when they are doing surgery?

P: I’d hope not!

Jogi: But are they still aware?

P: Yes, I’d hope so!

Jogi: Then there is awareness even when there is no introspection. You are that Awareness - the Purusha - the Witness of the mind, the body, and the world.

In Yoga, there are only two fundamental entities - Purusha and Prakriti.

Purusha is You, the pure Awareness - the light that illumines everything that we know, including the mind itself. More on the Purusha here:

Prakriti is nature - everything that is observable - including the body, the senses, and the mind. After all, in any observation, there must be an observer, and an observed, and the two must necessarily be separate. More on Prakriti here:

P: How do we know that? Why can’t the mind observe itself?

Jogi: It certainly can - this is introspection. However, even in this case, one part of the mind observes the other, or one movement observes another. The buddhi observe the manas, or may observe memory or imagination. Also, even here, there is an awareness of the fact of introspection. That is, you are aware that you are introspecting.

P: Ok, but what about awareness itself - can’t that be the mind too?

Jogi: In a sense, yes. You are aware that you are aware. The secondary awareness - called chidaabhaasa - is a reflection of the primary awareness, called Purusha in Yoga, or chit in Vedanta.

P: Why can’t the primary awareness be the mind too?

Jogi: If it were, there would be an infinite succession of awarenessess being aware of each other. But this does not match our experience. We are aware of our awareness, and that is the end of it. In fact, when we are focused, we aren’t even aware of this awareness, we are simply aware.

Said another way, when we really dig into our experience, we notice that there are only really two things in all of reality - the Seer and the Seen.

The Seer observes the Seen; the Seen is observed by the Seer.

The Seer (ie. Purusha) is simple - it is like a light that shines upon everything around it, indiscriminately.

Just like the sunlight falls upon dirty puddles, flowers, trees, and clouds alike, the Purusha shines upon all of Prakriti. It does not change, but it illumines all change. It does not move, but illumines all movement.

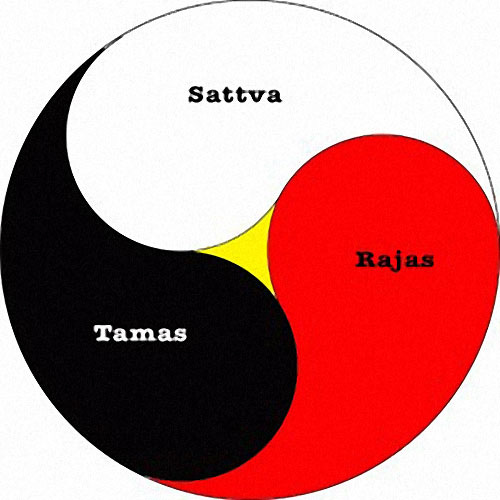

Prakriti, or nature, on the other hand, is constantly changing. It is the three gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas, in constant flux.

In our current situation, it seems that the two - Prakriti and Purusha - are conjoined. We are aware of our minds, our bodies, and the world around us. This apparent conjunction between Prakriti and Purusha is the cause of our sojourn in this Universe, and so, the cause of the suffering that it entails.

Let this sink in. This is not some fancy philosophy to be learned or studied, nor an idea to be believed in, but rather a reality to observe right now. There is no faith needed here, only careful and honest observation.

Look around you. You see forms, you hear sounds, you feel textures and sensations. These appear as movements in the mind with names, meanings, and associations. You can, in a sense, see these mental movements too. As you are reading these words, there is a voice in your head reading it to you - you can make it sound deep and slow or high pitched, you can make it raspy or even give it a British accent if you want to. Amazing, innit?

But notice, through all this, these objects are being experienced by You, the experiencer. No matter where the body goes, or what the mind does, the Experiencer remains, untouched, unblemished.

Prakriti: The Seen

The entire Universe is essentially made of three qualities - illumination (sattva), movement (rajas), and dullness (tamas). These three always exist together, but the quantities vary and shift continuously. The mind is more sattvic than your hand, which has more tamas in comparison. A gushing river is more rajasic than a still puddle, which is more tamasic. Wind has more rajas than still air, while still air has more sattva than a rock, which has more tamas.

The mind after a heavy meal has more tamas than a mind that is active (rajasic) after a cup of coffee. The same mind after meditation is more clear, and so more sattvic than before.

Everything - absolutely everything - can be seen as a combination of these three qualities, called the gunas.

The mind in Yoga: A recap

In Yogic psychology, the mind - known as the antahakarana (literally “the internal instrument”) - has three main functions:

Manas (मनस): The lower mind

Ahamkaar (अहंकार): The “I”-maker

Buddhi (बुद्धि): The intellect

The manas is the faculty of mind that flits between different options. It directs attention between the senses, and between different thoughts. An over-active manas results in rumination, mental loops, and a lack of decisiveness.

However, its functioning is critical to being attentive to one’s surroundings, and to weighing options rather than acting blindly.

The ahamkaar is the faculty of mind which takes credit for any and all actions of the body-mind. That is, when the legs move in a particular way, it is the ahamkaar that claims “I walked”. When the tongue moves in a particular way, it is the ahamkaar that claims “I spoke”. When the mind moves in a particular way, it is the ahamkaar that claims “I thought.”

It is useful, in that it provides a unitary idea of “self” that is much easier to manage and think about. However, in reality, the ahamkaar doesn’t do anything at all - the body and mind act, but this faculty of mind, like a bad manager, takes credit for all the work.

The buddhi is the most sattvic of the various faculties of mind, and is, therefore, most “proximate” to the Purusha. This is the faculty of mind which determines, decides, and differentiates. It is your buddhi which is able to distinguish each letter on this page from each other, and from the background. It is the buddhi which made the decision to sit down and read, as also the decision to scroll when you reach the end of the page.

The buddhi decides when to move, when to speak, how to speak, and how to move. All voluntary decisions are undertaken by the buddhi.

Since it is the most proximate to the Purusha, we often confuse ourselves with the buddhi. The fact that the ahamkaar is constantly taking credit certainly doesn’t help either!

Even in Dhaaranaa, when we decide to “bring the mind back to the breath”, it is the buddhi which notices that the mind has wandered, and the buddhi which decides to bring attention back.

More on the mind in Yogic psychology here:

How do Prakriti and Purusha interact?

Note: The word “object” as used in English most often refers to physical things in the world outside the skin. In the context of Yoga and Vedanta (as in the context of this newsletter), however, the word “object” can refer to thoughts, feelings, emotions, desires, sensations, the senses, etc. as well. Basically, anything that can be observed - including the act of observation itself - is an object.

A traditional example compares the relationship between objects and the Purusha to the relationship between iron filings and a magnet. The magnet attracts iron filings towards it due to its proximity. Then, those iron filings are able to attract other iron filings towards them, taking on the nature of the magnet.

Similarly, in a sense, objects are attracted to the Purusha (ie. Awareness), and take on its nature if they are proximate to it. Specifically, the more sattva an object has, the more likely it is to take on the quality of awareness, as though “borrowing” it from Purusha.

The most sattvic object in our experience is the buddhi, and so this is where the strongest confusion occurs. We most often feel like we are the buddhi, making claims like “I decided” or “I know.” This is the most convincing claim that the mind makes, and the most difficult to shake off.

The next most sattvic object in our experience is the ahamkaar. The ahamkaar leads us to claim “I spoke” or “I walked.” This confusion is less difficult to break out of than the confusion of Self with the buddhi, but nevertheless not that simple, especially given our conditioning to think in this way.

The manas is the next most sattvic object. The confusion of Purusha with the manas shines in phrases like “I heard this” or “I saw that”, when actually what happened was “an experience of sound” or “an experience of sight.” Other ways this confusion manifests are as “I couldn’t stop thinking about…” or “I am feeling sad/happy/excited…” The manas is moving in a particular way, but due to the proximity to the Purusha, we feel that it is actually us moving in this way.

The great philosopher Adi Shankaracharya compares these confusions to the illusion that the moon is moving when actually the clouds are the ones in motion.

P: But aren’t all of these just appropriation? And isn’t appropriation just the function of the ahamkaar?

Jogi: Yes. The function of appropriation happens through the ahamkaar. However, the ahamkaar is more likely to appropriate other aspects (ie. Tattvas) of the body or mind based on how sattvic they are. That is, the more sattvic the tattva, the more likely it is to be confused with the Purusha.

The Purusha remains unaffected

द्रष्टा दृशिमात्रः शुद्धोऽपि प्रत्ययानुपश्यः।DrashtaaDrishiMaatrah shuddho’api pratyayAnupashyahThe Seer is simply the power of Seeing. Although pure, It bears witness to the pratyayas.

- Yoga Sutra, 2.20

The traditional example compares the Purusha to a clear crystal placed near a flower. If the flower is red, the crystal will appear red. If the flower is yellow, the crystal will appear yellow.

Whatever colour is placed near the crystal, it crystal will appear to take on that colour. However, the crystal remains clear, through and through. Similarly, the Purusha appears to be coloured by the movements of the mind - the pratyayas which combine to form vrittis, or mental whirlpools, and kleshas, or mental afflictions. More on the vrittis and kleshas here:

When we suffer, we truly feel “I am suffering.” When we are happy, we truly feel “I am happy.” Even more subtle is the feeling of being a witness. It truly feels as though you are sitting behind your eyes, looking through them. However, if you notice closely, the feeling of sitting behind your eyes is in itself an object that appears within Awareness. You can notice the edges of this feeling, and see that it has parts. Who is it that notices this feeling? That one is the Purusha - You. The feeling of sitting behind the eyes is like the colour of the flower that the crystal takes on.

The Purusha and Prakriti are not, in fact, conjoined. It only feels that way. There is no real point of contact between the Purusha and Prakriti, just as the moon does not actually touch its reflection in a puddle.

We feel like the experience of the Universe is affecting us, but if we notice closely, we see that the changes happen, yet we remain. The thoughts appear and disappear, the feelings come and go, the world changes, the body ages, but the light of Awareness is completely unaffected.

This can be compared to the rays of the sun that shine on a dirty puddle and a clear lake. In both cases, the light illuminates them. Yet, the rays remain completely untouched.

P: Wait a second. If the Purusha remains unaffected, where is the suffering located?

Dukkha is within the realm of Prakriti

As discussed above, Prakriti is made of the three gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas.

When we are calm, clear, and peaceful, it is due to a preponderance of sattva. On the other hand, when we feel agitated, restless, or anxious, it is due to a rising of rajas. Finally, when we feel dull or tired, it is due to a high degree of tamas. All possible mental states are only slight variations on these three.

Out of these three possible states, we feel happiness only in the first.

That is, when sattva is dominant, and the mind is calm, clear, and blissful, we feel a sense of well-being, clarity, and peace. When we are agitated or restless, there is no happiness - we are simply hankering, thirsting for something we don’t have, often something we cannot even point out.

Even when we satisfy these desires born of rajas, the happiness does not last.

The reason that we feel happy when we satisfy a desire is because the rajas temporarily clears, and sattva shines through - like a small opening in the clouds on a rainy day. Then, the rajas returns, and the feeling of agitation and hankering returns.

When we are tired or the mind is dull, we also do not feel happy. The only way happiness can arise in the mind is when it is sattvic. Even when we feel happy by satisfying desires, it is because the rajas has temporarily cleared, and the natural state of sattva is momentarily shining through.

When the Awareness, ie. the Purusha, shines on the buddhi which is disturbed by rajas and/or clouded by tamas, we feel dukkha. On the other hand, when the Awareness shines on the buddhi which is sattvic, ie. undisturbed by rajas or clouded by tamas, we feel happiness. All objects - anything we can ever experience - are experienced within the buddhi, illuminated by the Purusha.

Said another way, the feelings of suffering or happiness - regardless of the actual objects of experience - are dependent entirely upon whether the buddhi is disturbed and clouded by rajas and tamas, or if it is sattvic. This is why even incremental progress in Yoga increases feelings of well-being and happiness.

This can be a huge revelation for many. There is no need to run around this world seeking happiness. Happiness is simply a matter of increasing the proportion of sattva in the buddhi - a matter entirely within our own control, that we can achieve through practice!1

Now the Purusha, as discussed above, is unaffected by the gunas. However, due to the apparent conjunction between Purusha and Prakriti, we feel as though “I am happy” or “I am suffering.” The mind misattributes the feelings of happiness and suffering to the Purusha itself, rather than recognising that these feelings are within itself.

This is like if one were to claim that electricity itself can show you your favourite TV shows, or wash your clothes. The TV displays your favourite TV shows, and the washing machine washes your clothes - the electricity simply powers them, and cannot function in these specific ways without the appropriate appliances.

Similarly, the Purusha simply illuminates and activates, as it were, the various functions of the mind, creating the wonderful display of the Universe that we see in front of us right now.

P: Wait, but the question still stands. Where is the suffering located? Isn’t it the Purusha who ultimately suffers?

In the fact of suffering, there is the suffering and there is the sufferer. The suffering is located in Prakriti, and is of the nature of rajas and tamas. The sufferer is not the Purusha, but sattva - the capacity of intelligence to know and perceive things, including suffering. It is compared to the sensitive skin on the soles of the feet. The Purusha is reflected in sattva just as the moon displays a reflection in a clear pool of water but not in the grass or the mud. In this way, while both suffering and the sufferer exist within Prakriti, the Purusha appears to be the sufferer, but is, in fact, altogether unaffected by the suffering.

P: So then if I am the Purusha, and the Purusha is untouched by suffering, why do I feel like I suffer?

Jogi: Because the mind has mistaken the location of suffering to be within the Purusha, when it is actually within Prakriti.

P: Right, but why is the mind making this mistake?

Jogi: Due to avidya - the Primal Ignorance.

This will be the focus of our discussion next time as we continue our discussion into the cause and prognosis of dukkha.

Next time: The Prognosis: Kaivalyam

Beware of spiritual bypassing here! Just because increasing the proportion of sattva is within our own control is not to say that it is unimportant or meaningless to solve the problems that exist in our lives and the lives of others. Quite the opposite. The practice of Yoga simply gives us the peace and clarity required to solve these problems head-on, without the clouding of disturbing thoughts.

Brilliant!