“If you meet the Buddha, kill him.”

How to deal with lapses in Kaivalyam

You can ask questions anonymously by clicking the button below. Some answers may be included in future articles:

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

तच्छिद्रेषु प्रत्ययान्तराण्यस्मीति वा ममेति वा जानामीति वा कुतः क्षीयमाणबीजेभ्य पूर्वसंस्कारेभ्य इति।TatChhidreshu pratyayaAntaraAnyaAsmiIti vaa mamaIti vaa jaanaamiIti vaa kutah ksheeyamaanaBeejebhya poorvaSamskaarebhya itiIn the lapses [of Kaivalyam], other thought patterns arise, such as “I am”, or “This is mine”, or “I know”, etc. From where [do they arise]? From residual samskaaras, whose seeds are in the process of being destroyed.

- Vyasabhashyam on Yoga Sutra, 4.27

Over the past several weeks, we have been discussing Yoga in the light of the fourfold method used by doctors in traditional Indian medicine to communicate with their patients:

Rogah (रोगः): The Diagnosis

Hetuh (हेतुः): The Etiology, or the Cause

Aarogyam (आरोग्यं): The Prognosis

Bhaishajyam (भैषज्यं): The Treatment

We have discussed the diagnosis - dukkha.

The cause of dukkha is the apparent conjunction between the Seer and the Seen - of Prakriti and Purusha.

This conjunction has a further cause - avidya - the Primal Ignorance which manifests as the confusion between Self and non-self. Avidya, like any ignorance, does not have any further cause - it is causeless and beginingless.

The prognosis, as we have discussed, is good. There is a way out of dukkha, and this “state” is known as Kaivalyam - Absolute Independence - and goes by many names in the various traditions of the world.

Last week, we discussed the final turning point towards Kaivalyam. When the Yogi sees the distinction between the Seer and the Seen for themselves, directly, in meditation, a change occurs in the Yogi where the mind tilts irreversibly towards Kaivalyam.

At this point, the gravity of this initial insight is sufficient to lead the Yogi towards final liberation.

However, the path is not yet completely clear. Along the way, there are obstacles in the form of residual samskaaras - mental impressions which, like seeds, sprout when the conditions are just right. These samskaaras pull the Yogi back into the world of bhoga, delaying the Final Release from dukkha, unless they are dealt with.

These “breaks” or “lapses” will be the subject of our discussion today.

Lapses in Kaivalyam

तच्छिद्रेषु प्रत्ययान्तराणि संस्कारेभ्यः।TatChhidreshu pratyayaAntaraani samskaarebhyahDuring the lapses [in vivek], other pratyayas arise because of previous samskaaras.

- Yoga Sutra, 4.27

The mind is, essentially, a pattern of movement. In Yogic terms, the gunas fluctuate in a certain way, and we call this particular pattern “the mind.”1

Some of these movements are more subtle than others.

To make this clear, let us use an example. Take a look at this picture.

What you are seeing is not actually the picture, but rather a movement in the mind. The light has entered your eyes, which then generated an electrical current, which then ran up the optical nerve. This electrical current runs into the brain, which is somehow2 perceived by You. The image you see is not the image, but rather a fluctuation of mind that resembles the image. This type of fluctuation, in Yogic psychology, is known as a pratyaksha-pramaana-vritti (प्रत्यक्षप्रमाणवृत्ति, literally a “direct perception-evidence-whirlpool”).

Now close your eyes and recall the image. Try to make it as clear as possible, remembering all the details as best as you can. Visualize it as clearly as your mind will allow.

This is also a vritti, but of a different kind. Specifically, it is known as a smriti-vritti (स्मृतिवृत्ति, literally “memory-whirlpool”).

Generally speaking, memories are less intense than the actual experience of the same thing.

In Yogic terms, smriti-vrittis are more subtle (aka sookshma) than pratyaksha-pramaana-vrittis, which are more gross (aka sthoola).

All mental activity3 lives somewhere on the spectrum of sthoola to sookshma - of gross to subtle. Memories of insignificant events are more subtle (ie. less gross) than memories of significant events. Fear is often more gross than slight preference, distant sounds are more subtle than loud, nearby sounds, and so on.

Initially, when we sit down for meditation, the first thing that we are likely to notice is that the mind feels somewhat chaotic.

There are many thoughts racing around - perhaps a song stuck in the back of your head, combined with feelings about uncomfortable sensations in the body, perhaps anxiety about when the timer will run out or how much time has passed, annoyance that meditation is difficult, and so on.

If we stick with it, even perhaps within the same sit, we find that these initial thoughts settle down, and other - more subtle - thoughts start to rise.

Perhaps memories about the last time you sat for meditation, a brief imagination about something that happened the other day, or something you are upset (or happy) about.

Normally, we write all of these thoughts off as “distractions”, but if we look carefully, we can notice a trend.

The first wave - the mental chaos, sensations, anxiety about the timer, etc. - feel “heavier.” They are more gross.

The second wave - imaginations, memories, etc. - feel lighter, more fuzzy or wispy. They are more subtle.

If we stay with the practice, this second wave of “distractions” also drops away, making way for even more subtle mental activity.

As each grosser wave rises and subsides - if we don’t poke and prod it with additional thought - it makes way for the next wave, which is more subtle than the last. This progression continues until thought patterns appear that you didn’t even know were there. Some of these may be so subtle that they cannot be put into words without disturbing the mind.

As an aside, this can be an important insight for folks who are new to meditation. We often feel like we have to somehow “force” thoughts to stop. This is a mistake, and can lead to suppression, which will then lead to the thought patterns bubbling up in unexpected ways. Instead, allow the thoughts to settle - wave after wave, getting progressively more and more subtle, while the attention is anchored to the aalambanaa (e.g. the breath, a mantra, etc.).

If we try to follow a single wave, and if our attention is sufficiently attuned to the subtlety, we will notice that it rises from somewhere, and it subsides back into that same source - like a wave that rises from the water, and subsides back into the water. In Yoga, this source - the “basement” of the mind - is called the karmaashaya - literally, the storehouse of karma.

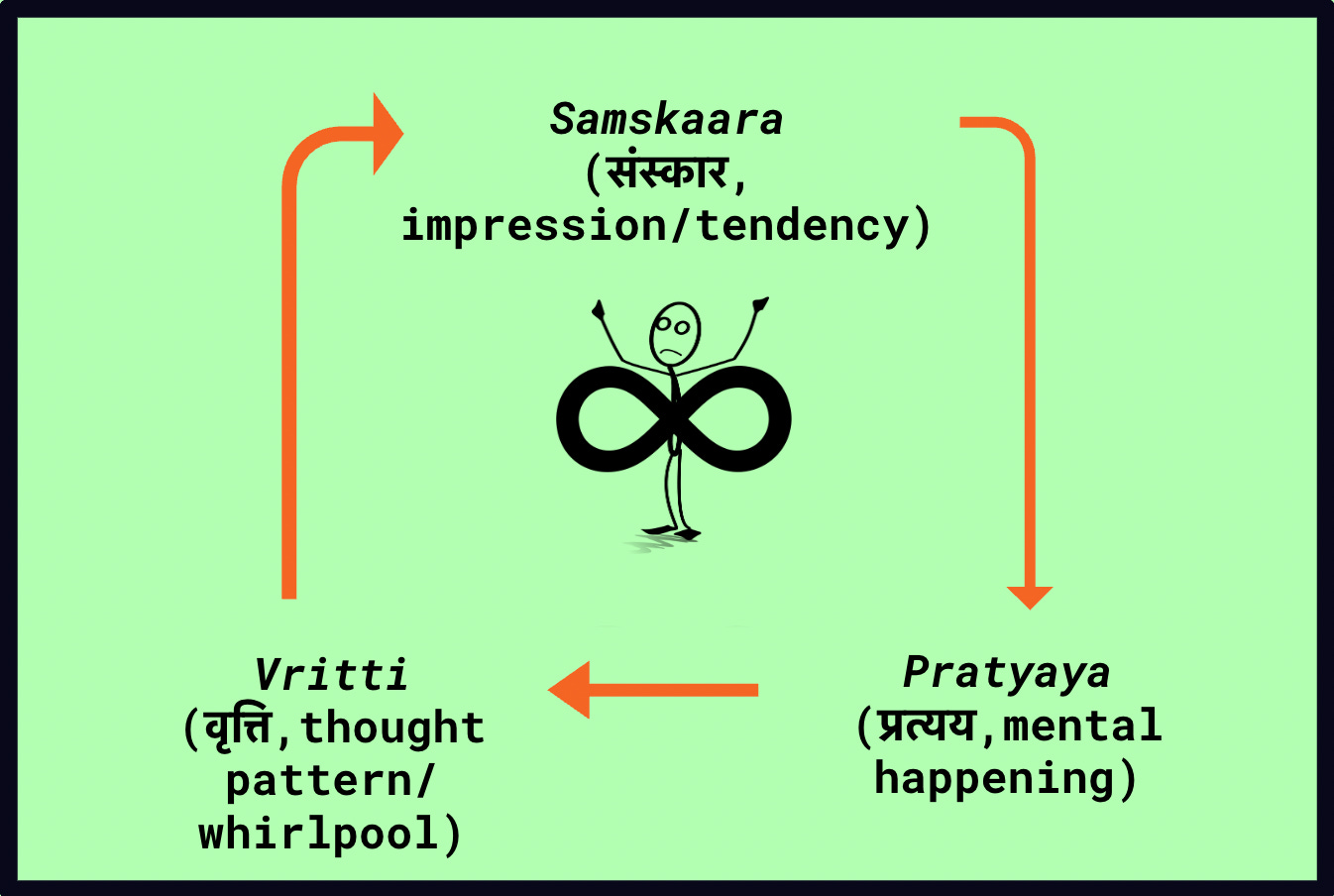

When the thought patterns are perceptible, they are called vrittis. These vrittis are composed of smaller pixel-like wavicles called pratyayas. These pratyayas arise from seeds, called samskaaras. It is these samskaaras that are stored (in a sense) in the karmaashaya.

When we “give in” to a pratyaya by paying serious attention to it or cultivating it, it generates further samskaaras, thus creating a cycle where the samskaaras increase in strength.

P: What does this have to do with Kaivalyam?

All of us are born with a certain set of seeds in the karmaashaya - a unique set of samskaaras4 that rise into thoughts, words, and actions when the conditions are just right. Some of these samskaaras pull us outward, towards bhoga (experience of the world), while others pull is inward, towards apavarga (liberation, or Knowledge of the Self).

When the initial insight of vivek - the distinction between the Purusha and the most sattvic aspect of the buddhi - arises, there are still samskaaras in the karmaashaya. These samskaaras, like seeds, are bound to activate when the conditions are appropriate.

For example, one may have an impression that pulls their mind towards anger or irritation when someone cuts them off in traffic. Despite the initial insight of vivek, the moment this person is faced with a situation where someone cuts them off in traffic, anger is bound to arise.

Anger, as we know, is fundamentally due to a separation between “self” and “other”, and an “ignore”-ance of the interdependence of all things. It is a manifestation of a sort of mental laziness where the mind does not take into account the various causal factors that led to a situation, and places blame upon a single factor, somewhat arbitrarily. Given this, anger is contrary to Kaivalyam, where it is seen that the causal factors themselves are mere convention.

So how can it be that a person who has had this insight previously still feels anger?

The reason is that previous samskaaras remain in the karmaashaya - hidden away in the basement of the mind. These samskaaras rise, and flower in the form of thoughts, words, and actions.

P: So even one we have the initial insight, there are lapses?

Jogi: Yes, lapses are a matter of fact, not of happenstance - not if, but when. They happen to everyone - even the most accomplished Yogis. As a matter of fact, you are (most likely) in a lapse right now! Just a very long one.

These “lapses”, known as chhiddraah (छिद्राः, plural of chhidra, literally “opening”, “tear”, or “aperture”), are inevitable. Samskaaras are many, and do not block the initial insight from their mere existence. They only create lapses when they bubble up to the surface.

P: What kind of liberation is this? I don’t want to have my peace of mind be dependent on external circumstances!

Jogi: Absolutely. It is not true freedom if one is dependent on anything.

P: So how do we become truly independent?

How to deal with lapses

हानम् एषां क्लेशवदुक्तम्।Haanam eshaam kleshaVadUktamThe removal [of these residual samskaaras] is described in the same way as [the removal of] the kleshas.

- Yoga Sutra, 4.28

The kleshas (literally “afflications”), as a brief reminder, are like colourings on top of thought patterns (vrittis). They are of five types - avidya (the Primal Ignorance), asmitaa (”I am”-ness), raag (attraction), dvesha (aversion), and abhinivesha (fear of discontinuity).

These five kleshas combine with vrittis to give rise to complex emotions such as regret, disappointment, and so on.

The more kleshas are present in the mind, the more unpleasant the mind is. The fewer kleshas, the clearer and calmer the mind feels.

Kleshas can be of varying degrees of intensity.

For example, with alcohol, one person may have a weak raag (attraction), and this manifests as them enjoying the occasional drink. For another person, it can be intense raag, and this can manifest as an addiction.

Yoga provides a systematic method to weaken the kleshas, starting with methods like eka-tattva-abhyaas, the Brahmavihaaras, the six stabilizing techniques, followed by Kriya Yoga, and then the sequential practice of the eight limbs. Through this practice, the kleshas get weaker and weaker, until eventually they become dormant - prasupta.

These prasupta kleshas are dealt with in Dhyaan and Samaadhi - meditation and absorption - the seventh and eighth limbs of Yoga, as described in the articles beginning here.

Residual samskaaras that arise after the initial insight of vivek are dealt with in the same way - by moving through them, observing them, and letting them go with vairaagya repeatedly until they wither away.

P: Why is it the same as the removal of the kleshas? What is the relationship to kleshas here, I thought we were talking about samskaaras?

The kleshas are ultimately the cause of all karma - of all action5. Samskaaras, or impressions, are at the root of all action. All samskaaras stem from kaam, or desire. Even the smallest, most insignificant actions, like shifting in your chair, or brushing your hair, come from a desire to, for example, be more comfortable, or look presentable.

Even taking care of the body - eating, sleeping, and so on - is the result of desire, even if it is subtle.

Desire manifests in the form of raag, dvesha, or abhinivesha - the final three kleshas. We want to go towards something, we want to move away from something, or we are afraid that something will stop.

These three kleshas are further the result of asmitaa, or “I am”-ness. There is a feeling that “I want”, or “I don’t want” - the “I” here is referencing the body-mind as separate from its surroundings, and appropriates objects and thoughts, thus generating the following three kleshas.

Finally, asmitaa arises from avidya - the Primal Ignorance which we have discussed at length - the root cause of all suffering. Avidya is the first of the five kleshas, and is like a field from which the others grow.

In this way, the samskaaras are ultimately caused by kleshas, and so the method to remove the samskaaras is by removing residual kleshas - moving through them, burning them with the light of attention, focused through meditation, as one may burn a leaf with sunlight focused through a magnifying glass.

These samskaaras can be seen clearly during meditation as patterns so subtle that they cannot be put into words without disturbing the mind.

As the samskaaras are cleared through the practice of meditation, the initial insight strengthens, like a sapling is strengthened into a tree when the weeds are removed.

Initially, the insight - the distinction (aka vivek) between the Purusha and the sattvic aspect of the buddhi - is extremely subtle. This is why it can only arise when the mind is extremely quiet.

P: Why?

Jogi: We confuse Purusha with the mind due to the constant mental fluctuations. It is like the reflection of the moon cannot clearly be seen in a pond with many waves or ripples. You cannot actually see the shape of the moon in the water until the water is completely calm. It is in the same way that the reflection of the Purusha in the sattvic aspect of the buddhi can only be clearly Seen when the mind is completely calm.

P: But doesn’t this insight also leave samskaaras?

The final vivek also leaves a samskaara in the mind. This samskaara is initially helpful, because it strengthens the practice and leads the Yogi further down the path to Freedom.

However, eventually, it must also be released - the Truth cannot be reduced to thought, and so the final act of meditation is to burn this very insight.

“If you meet the Buddha, kill him.”6

- Lin Ji

This final dissolution - like a flame burning up the last of its fuel - results in complete Independence, and the complete cessation of all suffering. This is Kaivalyam.

Next time: Nowhere to go, nothing to do

The very naming of the pattern of gunas as “mind”, “body”, “object”, and so on is in itself yet another movement of the gunas.

Currently unknown to modern science.

And everything we experience, including the “external” world.

The existence of this unique set of samskaaras per individual is a matter of direct experience. Some children seem to be born gifted as violinists and pianists, while others have to practice for years to reach the same degree of achievement. Every individual seems to gravitate towards something or the other. All effects must have a cause, and so the question may arise - where did these samskaaras come from to begin with? This is the rationale for the theory of reincarnation. After all, if a baby has samskaaras in the mind at the time of birth, they couldn’t have come out of nowhere - that would be magical, illogical thinking.

Specifically, of all appropriated action, where you identify as the doer (kartaa) and/or experiencer (bhoktaa).

This quote has several additional meanings, relevant in different contexts. For example, one meaning is that if we think we have understood the Truth, it means that we have conceptualized it - we have “met the Buddha”. Since we have conceptualized it, it is a concept, which cannot be Truth (since all concepts are conditioned - subject to impermanence, interdependence, etc., and without fundamental existence, like a “pot” is nothing but clay). Since it is not Truth, we must “kill the Buddha” by cutting through this conceptualization, in order to Realize the Truth, which is beyond concept.