Use the boat to cross, and then leave it behind.

Nirbeeja Samaadhi: Samaadhi without seed, and the highest form of "letting go"

Note: In order to gain more context for the story below, or if you are curious to learn about what the gunas are, it may be helpful to read this article first:

"You" are just nature.

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers. Welcome back! For the past two weeks, we have been going over the 25 Tattvas, or the 25 categories of the Universe from the Sankhya philosophy, which underlies Yoga. We have now covered the entire

You can also ask any questions (anonymously, if you so please) here:

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Once, a merchant was returning home to his village after a busy day at the marketplace, carrying a bag of money over his shoulder. The bag was heavy, and so he was walking a bit slower than usual. As he walked, he noticed that the sun had started to set, and he began to worry that he would not make it home in time for dinner with his family. In order to get back in time, he resolved to take a shortcut to the village through the forest.

Little did he know that the forest was home to a band of three robbers. As soon as he set foot in the forest, the robbers noticed him, and began to quietly follow him.

Suddenly, as they reached the center of the forest, the robbers came out of the bushes and ambushed him, and one of them, called Tamas, hit the merchant over the head, knocking him out.

“Let’s just kill him and take the money”, said Tamas.

“No need, let’s just tie him to the tree”, said Rajas.

As Rajas grabbed a rope and tied the merchant to the tree, the third robber, Sattva silently watched. Once the merchant was all tied up, Tamas picked up the bag of money and the three robbers ran off into the night.

After some time, the merchant woke up, and opened his eyes to see one of the robbers standing over him. It was Sattva.

“I want to help you”, said Sattva, as he began to untie the merchant from the tree.

Once he was done untying the merchant and helping him to his feet, Sattva noticed that the merchant was too confused to know which direction to go. Speaking kindly, he said “Let me show you the way out of the forest.”

The merchant followed Sattva through the forest, and finally, they saw the road to the village. Sattva pointed the merchant in the direction of the village, and started to say goodbye.

“Wait a second, where are you going?”, said the merchant.

“Back into the forest”, Sattva replied.

“I cannot thank you enough for setting me free. I would love to repay your kindness by having you over for dinner with my family. Please do me the honour!”, said the merchant, full of love and gratitude.

Sattva replied, “Unfortunately I cannot follow you into the village. They will not accept me there. After all, I am a robber, just like my friends.”

The definition of Yoga is:

योगश्र्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः॥YogasChittaVritti NirodhahYoga is the mastery of the vrittis in the chitta.

- Yoga Sutra, 1.2

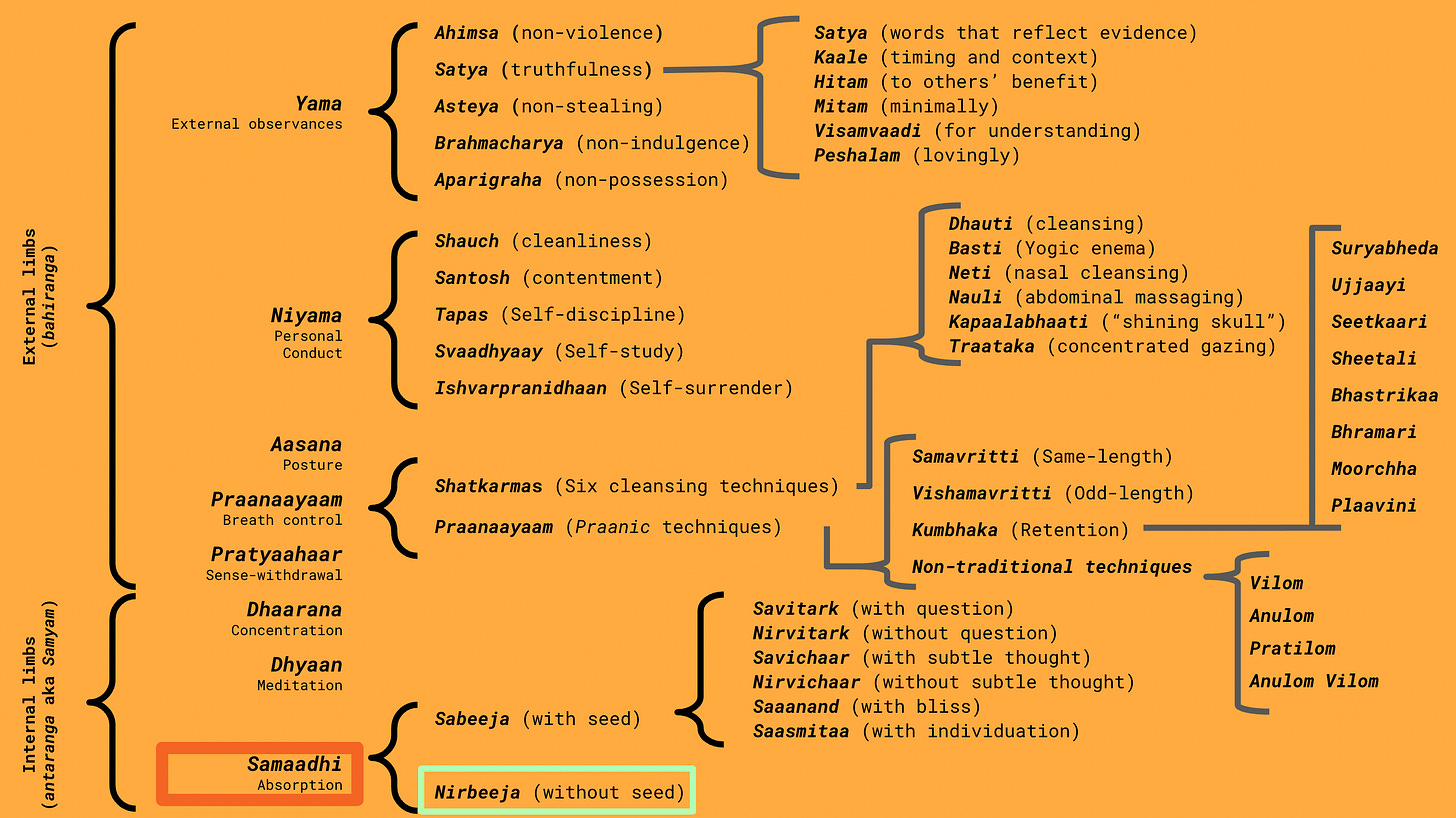

At this point in our journey, we have discussed the entire path of Yoga - the fundamentals of practice and letting go, the foundational techniques to calm and settle the mind, the method to build up energy, will-power, and vigour (ie. Kriya Yoga), and the eight-limbed path.

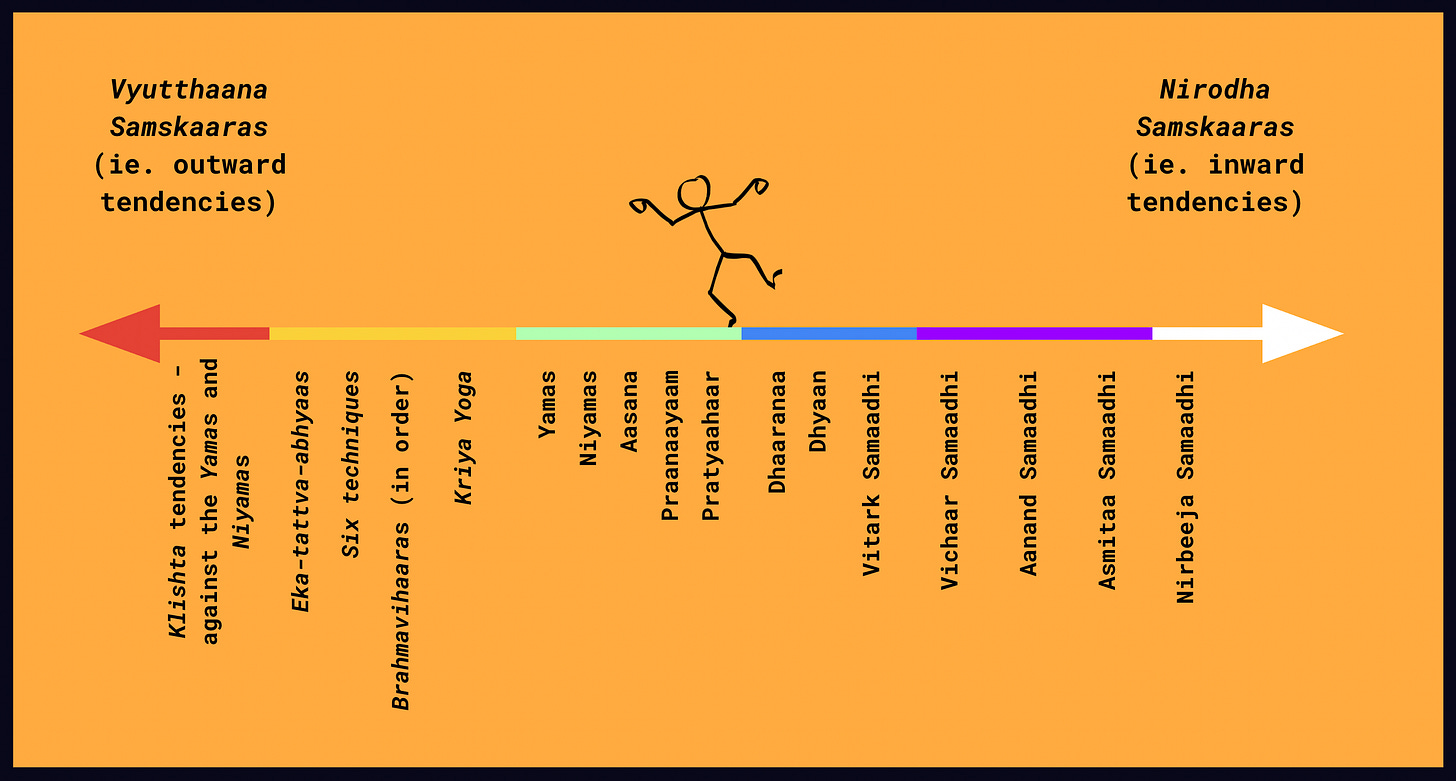

Normally, before Yoga, the mind has a natural outward tendency. That is, our tendencies draw our attention out towards the objects of the senses. This includes physical objects like delicious food, nice places, beautiful things, and so on, but also includes mental objects like wealth, power, identity, meaning, and so on.

As we practice, we may notice that the allure that certain objects once held starts to dissipate.

Where we once may have wanted to go out and party every night, we now prefer to sit at home. Where we once may have enjoyed drinking, smoking, or eating delicious food, we are now content with simple food and water. Where we once perhaps needed a lot of sense stimulus in order to satisfy the mind, or felt bored easily, we now naturally feel calm and peaceful, without the need for any external objects or sense stimulation.

Said another way, where we once had a lot of vyutthaana (outward) tendencies, they have now been replaced by nirodha (inward) tendencies.

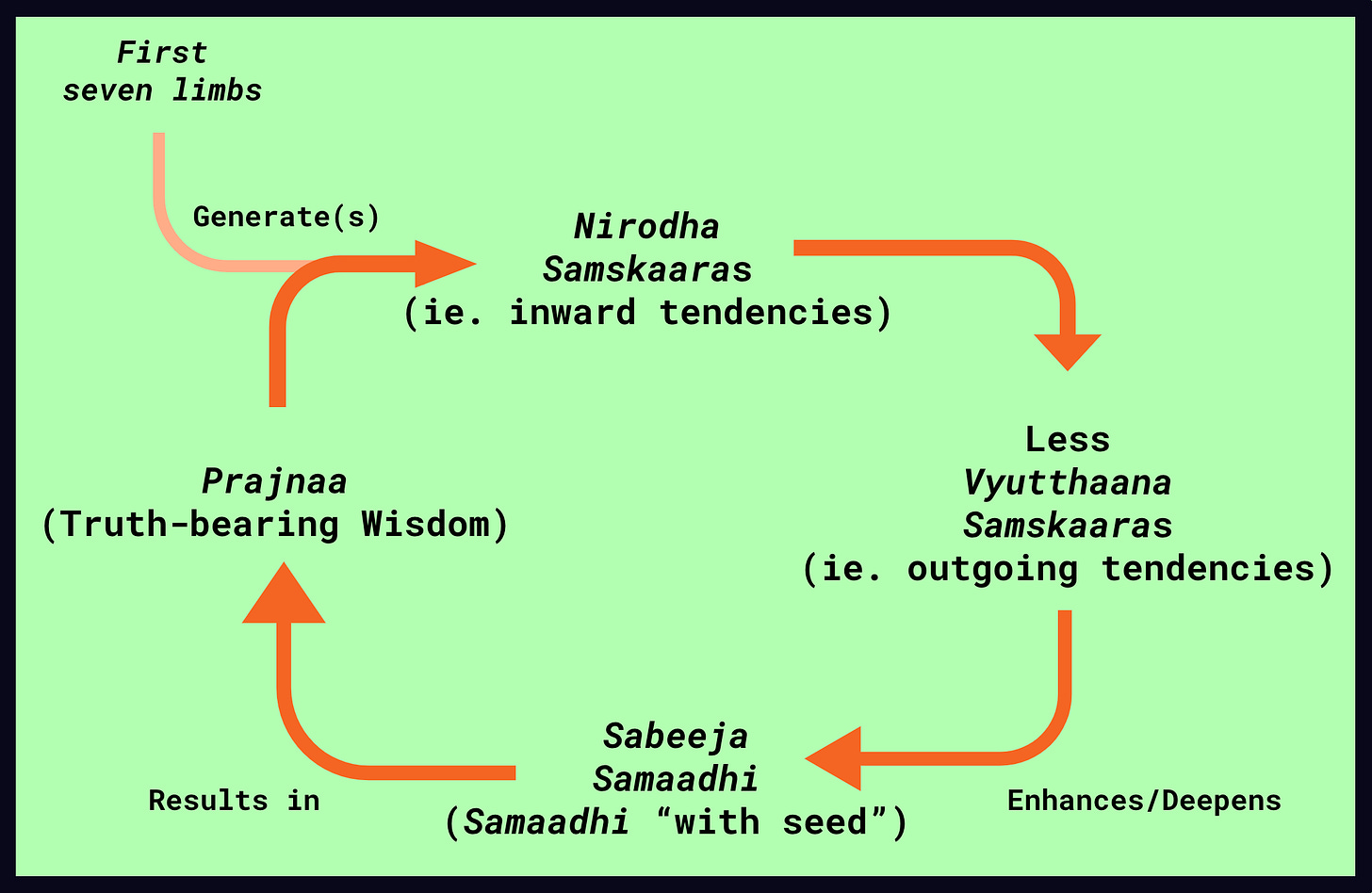

The reason for this, as discussed last week, is that Yoga is, in essence, a systematic method to reduce vyutthaana samskaaras (outgoing or gesticulating mental impressions), and generate nirodha (inward) samskaaras, thus creating a flywheel effect that generates more and more nirodha samskaaras over time.

P: Why do we want to generate nirodha samskaaras in the first place? I thought the goal was freedom from suffering?

Jogi: In order to truly destroy a weed, the roots and seeds must be removed. In the same way, in order to truly become free from suffering, we must remove the seeds that generate it.

P: So are vyutthaana samskaaras the cause of suffering?

Jogi: In a sense. These outgoing tendencies pull attention outward towards objects, which are all impermanent and unreal by nature. These tendencies are the reason that we are able to fool ourselves into thinking the impermanent objects that cause suffering are permanent, and will generate happiness, even when we experience the suffering firsthand. This “fooling ourselves” is known as avidya, or the Primal Ignorance, and is the root cause of all suffering.

P: Ok, but aren’t “nirodha” and “vyutthaana” just relative terms?

Jogi: Yes.

P: So if nirodha samskaaras also a type of seed, and if the goal is to get rid of all the seeds, then isn’t that contradictory? Doesn’t this mean that no matter how much Yoga we do, we are still just generating seeds which will sprout again, giving rise to further effects? And if so, doesn’t that mean that all of this is completely futile?

The question from our friend P here is, in fact, a deep philosophical objection.

We have discussed how the terms “nirodha” and “vyutthaana” - inward and outward tendencies - are just relative terms. For example, a tendency towards concentration is inward when compared to a tendency towards speaking ill of others, but is outward when compared to a tendency towards Samaadhi.

Given this, no matter how nirodha, or inward, a tendency gets, it is still, ultimately, a seed that will eventually sprout in the form of thoughts, if not words or actions.

This seems to mean that there is no possibility of Nirbeeja samaadhi - Samaadhi without seed - since nirodha samskaaras are just another type of seed.

What’s more, it seems to mean that no matter how much we practice, and no matter how amazingly nirodha our samskaaras get, we are trapped in the cycle of karma, and have no way out!

Lucky for us, this objection is not based on a complete understanding.

Removing one thorn with another.

A traditional example explains how when a thorn has gotten stuck in the skin, a person can take another thorn, use it to remove the first one, and then throw both thorns away.

Another example is that of a person crossing a river with a boat to get to their village on the other side. They use the boat to get from one bank to the other, but once they have arrived, they leave the boat at the bank and walk to their destination.

A final example is that of a person using a brick to knock on the door of a friend’s house. They use the brick to knock on the door, but do not carry it inside with them.

The goal of Yoga - chitta-vritti-nirodha - requires the Yogi to nullify all the seeds in the mind, not just the outgoing ones.

That is, even the most subtle nirodha samskaara - the seeds generated in the mind through Samaadhi - are ultimately still seeds, and all seeds can grow back given the right circumstances.

The question then arises, how can one nullify the effect of these extremely subtle samskaaras?

विरामप्रत्याभासपूर्वः संस्कारशेषोऽनयः॥ViraamaPratyaabhaasaPoorvah samskaaraSheshoAnyahThe other [Samaadhi, aka Nirbeeja/Asamprajnaata Samaadhi], where the Samskaaras become latent, is preceded by the practice of that which leads to the notion of termination (aka Viraam-Pratyaabhaas).

- Yoga Sutra, 1.18

P: That sounds confusing. What is “that which leads to the notion of termination”?

The viraama-pratyaabhaas, or the cause of the thought of thought-termination, is known as Para-Vairaagya - the highest vairaagya, or the highest “letting go.”

P: Ok, what’s that?

As discussed previously, vairaagya - non-attachment, desirelessness, or “letting go” - is one of the twin foundations of Yoga (the other being abhyaas, or practice).

It is defined as:

द्रिष्टानुश्रविकविशयवितृष्णस्य वशीकारसंज्ञा वैराग्यम् ॥DrishtAanushravikVishayVitrishnasya VasheekaarSangyaa VairagyamVairagya is the controlled awareness of one without craving/thirsting for objects, whether perceived or heard about.

- Yoga Sutras 1.15

This kind of vairaagya - although it has tremendous benefits on one’s well being, and is fundamental to any progress in Yoga - is ultimately of an objective nature, since it is opposed to objects.

That is, when you push something away, the effect on the mind is still of the same nature.

Therefore, since this vairaagya is at the level of the mind, and specific to objects, which are fundamentally nothing but the gunas, this vairaagya is also of the nature of the gunas.

विषया विनिवर्तन्ते निराहारस्य देहिन:।रसवर्जं रसोऽप्यस्य परं दृष्ट्वा निवर्तते॥Vishayaa viniVartante nirAahaarasya dehinahRasaVarjah raso’ApiAsya param drishtvaa nivartateThe embodied one may systematically restrain the senses from their objects, but the taste for sense objects will remain [in the mind]. However, upon seeing the Highest, even this taste dissipates.

- Bhagavad Gita, 2.59

This kind of foundational vairaagya is also known as apara-vairaagya, or “the lower” vairaagya.

That is, despite having a strong sense of vairaagya, the taste for the objects of the senses will remain as latent seeds in the Yogi’s mind, and can become activated given the right circumstances.

On the other hand, the higher vairaagya - known as Para-Vairaagya - is the ability to let go of the gunas themselves - not just their evolutes.

तत्परं पुरुषख्यातेर्गुणवैतृष्ण्यंTatParam purushaKhyaaterGunaVaitrishnyamThe higher [Vairaagya, is characterized by] non-thirsting for the gunas, [and in which there is] clarity of the Purusha (ie. the Self).

- Yoga Sutra, 1.16

In the story of the robbers and the merchant at the beginning of this article, the merchant could only become free of the ropes tying him to the tree (ie. desire, born of Rajas, tying us to the objects of the world) with the help of Sattva.

This is the lower vairaagya, and is foundational to any progress in Yoga.

However, in order to ultimately get back home to his village, the merchant needed to let go of Sattva as well.

In the same way, while Sattva helps us to clearly distinguish between Purusha and Prakriti (at the level of Asmitaa Samaadhi), we must ultimately leave Sattva behind in order to be completely free.

This is the higher, Para-Vairaagya, and is, in a sense, the most nirodha of all possible samskaaras.

P: But isn’t it still a samskaara after all?

Take a look at the diagram below. The first line is red on a yellow background. In the second line, we see a dashed line with some red, some orange, and some yellow.

Next, the third line is a orange and yellow line.

Now this is only a manner of speaking. We can say it another way - that is, the third line is an orange dashed line, on a yellow background. Specifically, the yellow is not a colour in itself, but rather a break in the orange line.

We can describe yellow dashes as dashes in themselves, or we can describe them simply as gaps in the orange line.

Para-Vairaagya Samskaaras are like this. For the sake of convenience, because, as Yogis, we are used to thinking in terms of samskaaras, Para-Vairaagya can be described as a nirodha samskaara. However, it is the most nirodha of all nirodha samskaaras, and is, in itself, not of the nature of the gunas.

That is, Para-Vairaagya is like a break in the line, rather than an explicit dash in itself.

P: Why does this matter?

Samskaaras are like seeds which sprout into karma (action) when the conditions are right. The sprouts then leave further seeds, and so the cycle of karma continues. This cycle is known as samsaara - the cycle of birth and death, or the cycle of continuous suffering.

However, the Para-Vairaagya Samskaara is not really a seed, but a gap in the stream of samskaaras.

As a result, it does not sprout, nor does it deposit any new seeds.

When the gap becomes sufficient, it results in Asamprajnaata Samaadhi - the highest Samaadhi. This is also known as Nirbeeja Samaadhi, or “Samaadhi without seed”, since it does not leave any seeds in the mind.

P: Wait a second. If it doesn’t leave any seeds in the mind, how do we even know that this state exists?

Jogi: What do you mean?

P: In order to know something, it must be either perceived, inferred, or heard, ie. it must come through a Pramaana. Is that correct?

Jogi: Yes.

P: And knowledge through pramaanas can only be known through memory, which relies on the traces left in the mind. Correct?

Jogi: Yes, that is correct.

P: Ok. But this experience - Nirbeeja Samaadhi - leaves no trace on the mind, is that correct?

Jogi: That is also correct.

P: So then how can it be known to exist?

It is true that we cannot know the state directly through memory as we know all other things. However, we can know that it exists through inference, based on the movement of time once you are out of the state.

That is, if it is morning when you go into Nirbeeja Samaadhi, and then you get out, it will feel like no time has passed, and so you will not know if you went into Nirbeeja Samaadhi. But then if you look at the time and see that it is later in the day, you can infer that you were in Nirbeeja Samaadhi during that time.

We do not remember it directly, since it leaves no trace, but we can infer it from the passage of time after we get out of it.

This final state of Nirbeeja Samaadhi is unique because it is not an experience of something. It is, rather, an experience of absence. The first time it happens, it can feel accidental, like time just slipped away and you didn’t notice - nothing special.

Through repetition, however, it becomes clear that You, the Purusha, continue to exist regardless of any experience of the world, the body, or the mind. That is, it becomes clear that you are, and have always been, utterly separate from the body and mind.

On its own, Nirbeeja Samaadhi is not the same as Moksha, or freedom.

However, when this Samaadhi is used in the context of the overall teaching, the pieces of the puzzle start to come together, and the entire Universe, including the body and mind you once called “me”, become nothing but a play of names and forms in the infinite dance of Prakriti.

Until next time:

Recap the article on Vairaagya, and work to strengthen this foundation. Notice how this practice affects your daily meditation. You can find more on this practice of “letting go” here:

Letting Go

·Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers. Wanting to know the secrets of the Universe, and desiring freedom from all suffering, a student traveled into the mountains. He had heard about a legendary teacher who lived in a cave who would be able to answer all his questions and lead him to

Ask your questions here:

Next week: The three transformations: The internal workings of the mind in Samaadhi