Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

“So to meditate is to purge the mind of all self-centered activity. And if you come this far in meditation, you will find that there is silence, a total emptiness. The mind is uncontaminated by society; it is no longer subject to any influence, to the pressure of any desire. It is completely alone, and being alone, untouched, it is innocent. Therefore, there is a possibility for that which is timeless, eternal, to come into being. This whole process is meditation.”

- Jiddu Krishnamurti

Everything that we do - every thought, word, and action - leaves an imprint on the mind.

These imprints are known as samskaaras, and can be likened to seeds.

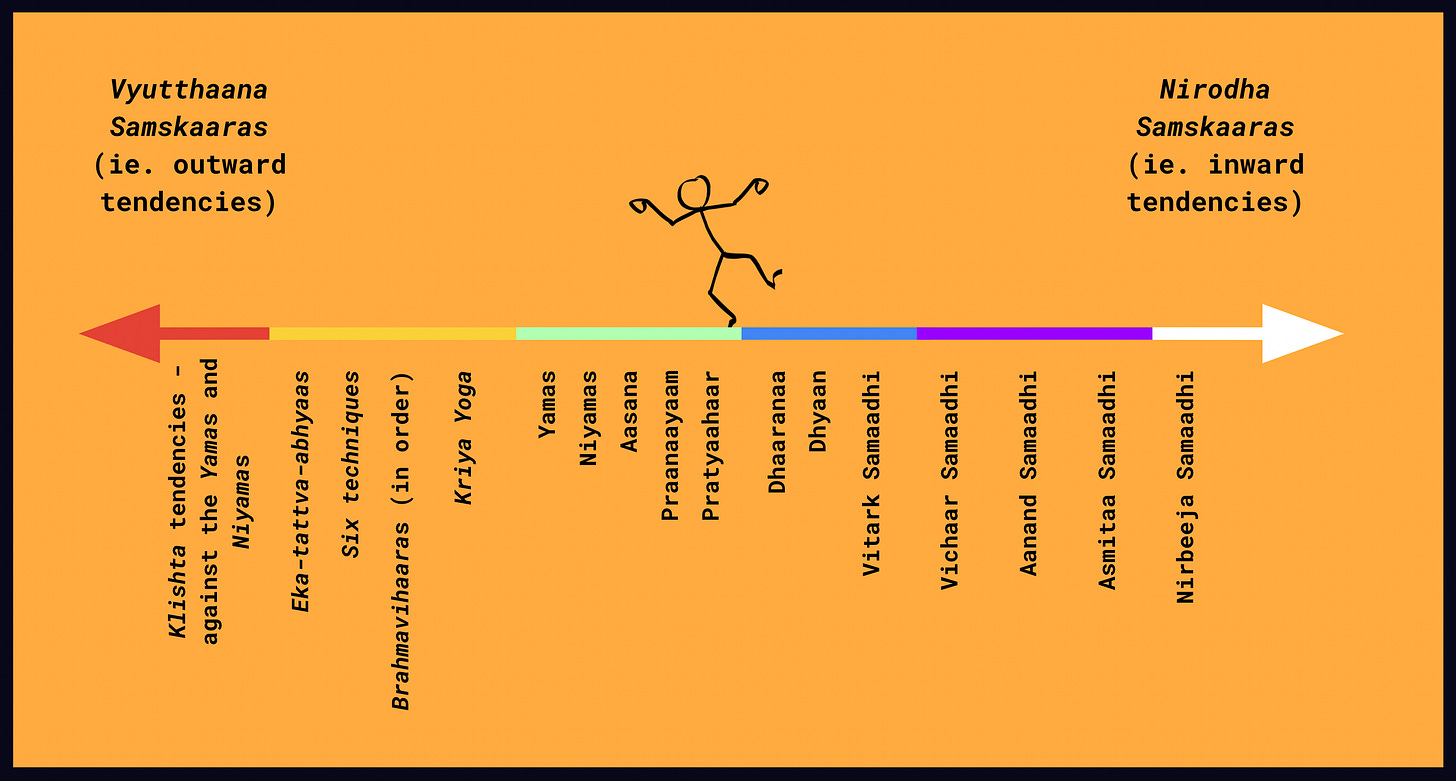

These seeds are of two types:

Vyutthaana Samskaaras (व्युत्थान संस्कार): Outward, or gesticulating samskaaras, or impressions

Nirodha Samskaaras (निरोध संस्कार): Inward, controlling, or “mastery” samskaaras, or impressions

When the conditions are just right, Vyutthaana Samskaaras sprout into karma - thoughts, words, or actions. These seeds pull attention outwards, toward the objects of the world.

Nirodha Samskaaras, on the other hand, have a calming or negating effect on the outward samskaaras. That is, they pull attention inwards, toward the Self.

The various techniques of Yoga that we have discussed in this series are essentially actions - karma - just like any other.

The only difference is that while other actions generate vyutthaana or outgoing samskaaras, Yogic techniques generate nirodha samskaaras.

P: So what exactly are vyutthaana and nirodha samskaaras?

“Outward” and “Inward” are relative terms

Vyutthaana and Nirodha Samskaaras are more like categories of impressions rather than specific impressions.

What’s more, these terms only have meaning relative to each other. That is, an impression is not outward or inward on its own. It is only outward or inward relative to another impression.

To make this clear let us consider an example.

Before beginning Yoga, a Yogi had a tendency to tell lies.

This tendency was a seed - a samskaara - which manifested when the conditions were just right. For example, this Yogi found that they were more likely to tell lies when they were amongst a certain group of friends, but less likely to tell lies when they were with their significant other. They also found that they were more likely to tell lies when they were faced with a stressful situation, but less likely to tell lies when they felt relaxed. Just like a seed in the soil, the seed of telling lies would sprout only when the mental conditions were just right.

Then, when the Yogi began on the path of Yoga, they decided to uphold the second Yama - satya, or truthfulness.

In the beginning, it was extremely difficult. The Yogi would sit with their group of friends, and when the friends would tell outlandish stories about themselves, lies would begin to bubble up in the Yogi’s mind. At first, it bubbled up into words, and they broke the Yama. Then, they felt bad about it, and resolved to not lie the next time using the technique of Pratipakshabhaavanaa.

The next time they sat with their friends, despite their resolve, a lie bubbled up once again. Again, they felt bad and resolved to not lie the next time around.

Finally, one day, the Yogi was able to catch themselves just as the thought of the lie was about to bubble up into words.

The next time, they were once again able to catch themselves before the thought of the lie bubbled into words, and over time, repeating this practice - despite some hiccups along the way - it became easier and easier to not tell lies.

Notice how this action - in line with the Yama of truthfulness - was comparatively more inward, masterful, or restraining, than the action of the mind bubbling into lies.

What’s more, by repeating this process, two things happened:

The tendency to tell lies became weaker.

The tendency to tell the truth became stronger.

Said another way, in one fell swoop, the nirodha samskaara became stronger, and the vyutthaana samskaara became weaker.

If a person is traveling towards the East, they need not make any additional effort to move away from the West.

Now in this scenario, the tendency to tell lies was more outward, or vyutthaana, than the tendency to tell the truth, which was more inward, or nirodha.

However, the tendency to tell the truth is still more outward than say the tendency towards Dhaaranaa (concentration, the sixth limb), where attention itself is held to a particular object, and returned to that object every time it wanders.

When compared to the tendency towards Dhaaranaa, the tendency towards Satya, or truthfulness, is outward (vyutthaana), and the tendency towards Dhaaranaa is inward (nirodha).

Similarly, the tendency toward Dhaaranaa is itself vyutthaana when compared with the tendency toward Dhyaan, which is itself vyutthaana when compared with the tendency toward Samaadhi.

Finally, the tendency toward Sabeeja Samaadhi (the first six levels of Samaadhi discussed thus far) is vyutthaana when compared against the tendency toward Nirbeeja Samaadhi (Samaadhi without seed, or without support).

तदपि बहिरङ्ग निर्बीजस्य।TadApi bahirAnga nirbeejasyaEven these [Samyam, aka Dhaaranaa, Dhyaan, and Sabeeja/Samprajnaata Samaadhi] are external limbs in comparison to Nirbeeja [Samaadhi].

- Yoga Sutra, 3.8

The virtuous cycle: The role of Prajnaa in generating Nirodha Samskaaras

As discussed over the past few weeks, the Sabeeja (aka Samprajnaata) Samaadhis after Nirvichaar generate a truth-bearing wisdom, known as Prajnaa, in the mind of the Yogi.

As a quick recap, regular perception - known as loka-pratyaksha - can only generate knowledge of generic categories, known as saamaanya. To use a traditional example, when we see a cow, the mind automatically categorizes it into a class called “cow”, and continues to apply different categories such as colours, shapes, etc.

In Samaadhi, however, the words and categories drop away, leaving the object - the vishesha, or specific - to shine alone, as it is. This type of knowledge is known as para-pratyaksha, or the higher perception, and when it becomes a natural tendency (with practice), it is known as Prajnaa - wisdom.

This Prajnaa - the knowledge of specifics, or vishesha - cannot be generated from regular perception, inference, or testimony. When it becomes strong, the Yogi no longer feels the urge to categorize or name objects of experience, and is able to see all objects (including their own minds) as they are, without the veil of thought that normally clouds our perceptions.

This wisdom, despite being extremely subtle, still leaves impressions in the mind. However, these impressions are more inward than any other impressions that the mind is capable of generating.

This is because, in a sense, they are extremely “light”, since they do not carry the weight of past conditioning (ie. language and categories - shabda and jnana).

Since these impressions generated from Prajnaa are highly nirodha, or inward, they are able to counteract the effects of other vyutthaana, or outgoing, impressions. When these outgoing impressions are counteracted over time, they weaken, thus strengthening and deepening Samaadhi.

Then, as Samaadhi becomes stronger and more stable, Prajnaa appears more frequently and witih more strength, thus generating more nirodha impressions.

This is the virtuous cycle of Samaadhi.

Over time, the nirodha samskaaras become so strong, and the vyutthaana samskaaras become so weak, that the Yogi’s mind automatically flows into Samaadhi without any particular effort. What’s more, the Yamas, Niyamas, and the other limbs of Yoga become their natural way of being, rather than a practice to be cultivated.

However, this is still not the final step.

P: What happens next?

The final stage: Nirbeeja Samaadhi

The very last stage in the eight-limbed Yoga goes by many names.

It is known as Nirbeeja Samaadhi - literally Samaadhi “without seed” - because it does not stem from, nor does it leave, any seeds, or impressions in the mind.

It is known as Asamprajnaata Samaadhi - literally Samaadhi without cognition, or without support - because unlike the other Samaadhis, there is no aalambanaa, or support for Awareness.

Finally, it is known simply as anya - literally “the other” - because it is beyond any words or concepts, including convention. Given this, it is not, strictly speaking, correct to speak about it at all.

However, that would not be very useful to a Yogi who is interested to know what comes next!

In particular, in this state, the Purusha - Pure Awareness - is no longer aware of anything at all, including the mind itself. All thoughts patterns have settled, like mud in a still pond, and the mind has become completely and utterly transparent so that it has entirely disappeared.1

Purusha is not like a light that can be switched on or off, but rather like the Sun. At night, the Sun has not disappeared - it is simply no longer illuminating the part of the Earth where you are situated. In the same way, in Nirbeeja Samaadhi, the Purusha - You - are still Aware, but you are not Aware of any objects - the mind, the body, or the external world.

Normally, we think that we are the body, the mind, or some combination. Then, after we study Yoga, we start to think that we are the Awareness shining on the mind and body.

However, even this perspective is limited, in that the very word “Awareness” is a concept, and is relational. That is, we feel, somewhere, that Awareness itself must be Aware of something.

In Nirbeeja Samaadhi, however, the Purusha is no longer aware of anything at all, and as a result becomes free from its apparent connection to Prakriti.

This freedom is the goal of Yoga.

Until next time:

Notice your samskaaras as they activate, and use the techniques of Yoga to generate progressively more nirodha samskaaras. Take notes to find patterns - these patterns are the impressions in your mind!

At the end of your meditation, when the bell rings, let go of your aalambanaa completely, and try to settle on the most subtle feeling of “I.” Watch it carefully. Who is it that watches?

Ask your questions here:

Next time: More on Asamprajaata Samaadhi.

Note that this analogy - like any analogy - is limited, because the mind is nothing but a combination of vrittis and samskaaras, whereas the water in a pond can exist without ripples or mud.