Note: The next few articles will be devoted to answering questions asked by readers. If you have questions, please submit them by clicking the button below.

Separately, this post may contain too many images to open in your email client. Please click on the title to view the whole thing in your browser.Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

When digging a well, in order to maximize the chances of finding water, is better to dig in a single spot than to dig a little bit in a lot of places.

This is the principle behind samyam.

Samyam is the term for the combined practice of the three internal limbs of Yoga - Dhaaranaa, Dhyaan, and Samaadhi.

It is this practice which is known colloquially nowadays as “meditation.”

Last week, we revisited six key concepts that are necessary to understand Samaadhi - meditative absorption - the eighth and final limb of Yoga.

The six concepts were:

Pravritti and Nivritti: Evolution and Involution

Shabda, Artha, Jnana: Word, meaning, and idea

Lokapratyaksha and Parapratyaksha: Regular and higher perception

Vyutthaana and Nirodha Samskaaras: Outward and inward tendencies

Samapatti: Engrossment

Grahitr, Grahana, Graahya: The grasper, the grasping, and the grasped

If you missed last week’s article, it may be helpful to go back and review it before reading on.

Samaadhi: Meditative Absorption

P: What is Samaadhi?

Samaadhi is defined as the state in which the aalambanaa shines forth in its own right, without the veil of word and idea.

Said another way, the moment the Yogi experiences parapratyaksha for the first time, that moment is Samaadhi.

Samaadhi is not a practice in itself - rather, it is a deepening of Dhyaan (meditation), which is, in turn, a deepening of Dhaaranaa (concentration).

That is, the Yogi cannot force Samaadhi voluntarily. Instead, they must practice Dhaaranaa until the mind becomes fertile ground for Samaadhi to occur.

Samaadhi is not the same thing as enlightenment, or Kaivalyam. It is rather a method through which the Yogi can tune their attention sufficiently to break through the bondage of karma and see Reality for themselves.

Finally, while it is helpful to categorize and discuss Samaadhi, it is important to remember that Samaadhi cannot actually be described in words. The reason for this is that Samaadhi is, by definition, beyond words.

The discussion of Samaadhi in words can be compared to symbols for rivers or mountains on a map.

The symbol for a mountain is a simple triangle - it is not the mountain itself, nor a very good description of the mountain. However, even though the description is inadequate for the purpose of experiencing the mountain in the mind’s eye, it is not without utility. That is, it can still help the traveller to recognize the mountain when they actually arrive at it.

In the same way, these descriptions are not to be taken too seriously - a traveller in search of a triangle will miss the mountain. However, the Yogi can use these descriptions to look out for these states while they are on their journey.

The levels of Samaadhi

The levels of Samaadhi are essentially differentiated by which component of knowledge - the grahitr, the grahana, or the graahya - the Yogi’s attention is rested upon.

There are two types of Samaadhi - sabeeja (with seed), and nirbeeja (without seed). Sabeeja Samaadhi is also known as Samrajnaata Samaadhi, and Nirbeeja Samaadhi is also known as Asamprajnaata Samaadhi.

The distinction between sabeeja and nirbeeja lies in the fact that in sabeeja samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention is supported by an aalambanaa, whereas in nirbeeja samaadhi, there is no support. As a result, sabeeja samaadhi leaves subtle traces or seeds (samskaaras) in the mind, while nirbeeja does not.

Sabeeja Samaadhi is further classified into four sequential categories, the names of which have similar consequence as the names of the elements in the periodic table (ie. not much):

Vitark Samaadhi: Samaadhi “with opinion”, or “with question”

Vichaar Samaadhi: Samaadhi “with thought”

Aanand Samaadhi: “Bliss” Samaadhi

Asmitaa Samaadhi: “I am-ness” Samaadhi

The first two of these are further broken down into a savikalp (conceptual) and nirvikalp (non-concepetual) version. In the savikalp version, word and idea are intermingled with the object. In the nirvikalp version, the object shines alone. For this reason, the savikalp versions are sometimes not classified as Samaadhi, since Samaadhi is defined by the fact that the object shines alone, without word or idea.

To make these levels of Samaadhi clear, we will use three different common aalambanaas as examples. Refer to the tables in each to see how each of these aalambanaas differ in their initial approach:

The breath

A mantra

A deity

While we are using these three common aalambanaas, remember that the Yogi can use any object at all for their aalambanaa. After a couple of levels, there is no longer any difference between which aalambanaa is chosen.

Vitark Samaadhi: Samaadhi “with opinion”

In Vitark Samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention is rested upon the gross level of the object. At first, it begins with savitark samapatti, where word and idea are intermingled with the perception of the object. However, the feeling of “I” has disappeared, and the object seems to be the only thing in all of existence.

Savitark samapatti is not technically Samaadhi, since word and idea are still intermingled with the object. Rather, it is like a doorway into Samaadhi.

After some time, if this state is stable, word and idea drop away, and the object shines alone.

This is nirvitark samapatti, and is, technically speaking, the first level of actual Samaadhi.

Here, time, space, and causation drop away, since memory has become inactive (and time, space, and causation all depend upon the presence of memory). This means that it feels like you are seeing the object for the first time - like it is the only thing in all of existence.

Take a look at the table below to see what happens to the three common aalambanaas in savitark and nirvitark samapatti.

Vichaar Samaadhi: Samaadhi “with thought”

In Vichaar Samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention moves beyond the physical layer of the aalambanaa, resting upon the subtle levels of the object.

Vichaar Samaadhi is in itself a sequential practice, with several sub-layers. In order to understand Vichaar Samaadhi and beyond, it is important to revisit the concepts of pravritti and nivritti discussed last time.

In Vichaar Samaadhi, the Yogi penetrates the objects subtle layers one by one, moving from the vishesha to the underlying saamaanya, then seeing that next saamaanya as a vishesha in its own right, and repeating the process from there.

For example, the Yogi first rests their attention upon the breath. Then, the attention penetrates a level deeper, resting upon the tanmaatras of texture and sound that compose the breath. That is, the Yogi no longer sees “breath”, but rather sees “texture” and “sound”, modified to have a particular name and form. The attention now rests upon raw texture and sound - the tanmaatras, as independent of time and space. After all, texture and sound are not limited by the boundary of the breath, and so attention expands, as time and space drop away.

Next, “texture” and “sound” are seen to be nothing but ahamkaar, and the Yogi’s attention rests upon the ahamkaar, with these special modifications. This is followed by the Yogi seeing the ahamkaar as just a special (ie. vishesha) modification of the buddhi, and finally with the Yogi seeing the buddhi as nothing but a modification of Prakriti.

In this way, the Yogi can involute (ie. nivritti) any object into Prakriti, seeing all objects - from physical objects like rocks, bodies, books, all the way to subtle objects like thoughts, ideas, and identity - as nothing but modifications of the same underlying Prakriti.

Vichaar Samaadhi is the most involved portion in the entire eight-limbed practice, and takes by far the most time and practice in comparison to all the other techniques.

Samaadhi can be difficult to stabilize, and this stage has many, increasingly subtle, sub-stages within it.

Between each level of nivritti, the Yogi’s attention alternates between savichaar and nirvichaar.

That is, at first, the tanmaatras are seen with name and categorization, then without name and categorization, before the Yogi’s attention penetrates to the level of the ahamkaar. The ahamkaar is then seen with name and categorization and then without name and categorization, before the Yogi’s attention penetrates to the level of buddhi, and so on.

This process cannot be forced - rather, it deepens on its own. Even without any knowledge of this sequence, the adept Yogi will achieve the same states. The only advantage to knowing this categorization is that you will recognize where you are, keep track of your progress, and accelerate by being mindful of the pitfalls of each stage.

Aanand Samaadhi: Bliss Samaadhi

The next stage of Samaadhi is known as Aanand Samaadhi - literally “Bliss” Samaadhi. The reason for this is that this stage is accompanied by a feeling of great bliss, and so is easily confused for the Ultimate Realization.

In Vitark and Vichaar Samaadhi (the previous two stages), the Yogi has involuted the entirety of the Universe all the way into the buddhi, and then into Prakriti. However, this was from the perspective of the graahya - the object of perception. Said another way, the objects of knowledge are now seen as nothing but Prakriti.

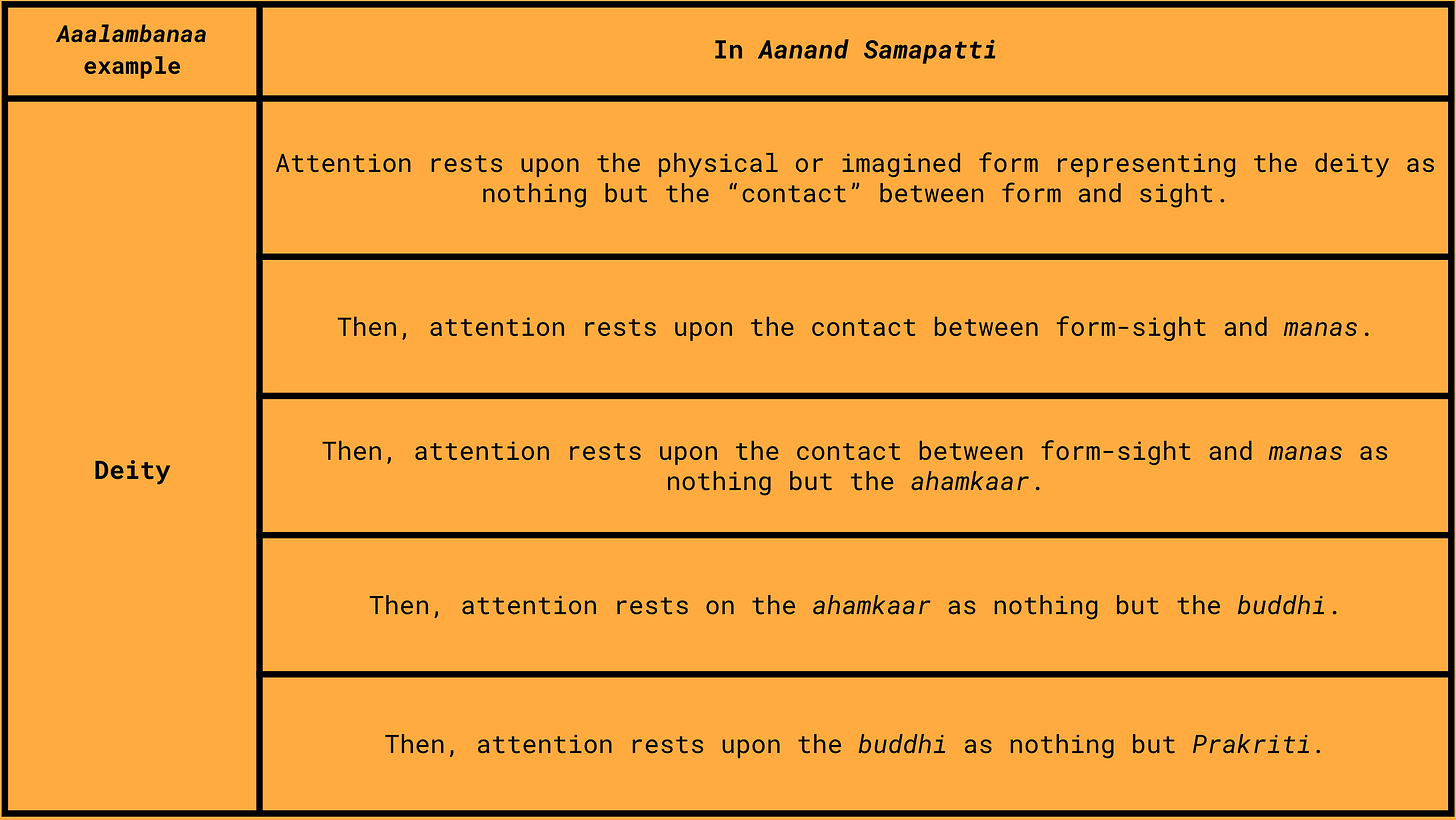

Next, in Aanand Samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention moves from the graahya to the grahana - the instruments of knowledge.

Normally, we think of our eyes as separate from the form they perceive. However, if we notice carefully, we will find that the sense of sight and form are interdependent. There is no form without the sense of sight to perceive them, nor is there a sense of sight without form to be perceived.

In this way, they are not two things, but one - a “contact” between sense and tanmaatra - sight-form, if you will.

This is also true for the other senses and their respective tanmaatras (e.g. sound-hearing, texture-touch, etc.).

Furthermore, these “contacts” are themselves interdependent with attention, or manas. There is no sense contact without attention to illuminate them, and so it is a three-way contact between manas, the senses, and their respective tanmaatras.

Aanand Samaadhi begins here, at this interdependence, and uses the same process of nivritti to move inward, involuting the Universe into Prakriti through the path of the grahana.

Using the example of the breath, the process is as follows:

Dhaaranaa: The mind is brought to rest upon the breath. When it wanders, it is returned to the breath.

Dhyaan: The mind sticks to the breath.

Savitark Samapatti: The distinction between observer and breath disappears, and the breath alone shines.

Nirvitark Samapatti: The breath is seen without the name “breath” or the knowledge (ie. categorizations) into “inhale”, “exhale”, “breathing”, “soham”, “hamsa”, etc.

Savichaar Samapatti: The breath is seen as nothing but the tanmaatraas of texture and sound.

Nirvichaar Samapatti: The tanmaatraas of texture and sound are experienced without the name or knowledge.

Aanand Samaadhi begins here: Texture and sound are seen as interdependent with the senses of touch and hearing. For example, rather than texture sensed by touch, it is seen as a singular contact of texture-touch.

Texture-touch and sound-hearing are seen as interdependent with manas.

Texture-touch, sound-hearing, and manas, are seen as nothing but the ahamkaar.

The ahamkaar is seen as nothing but the buddhi.

Buddhi is seen as nothing but Prakriti.

Look at the examples in the table below to see how no matter what your aalambanaa, it will eventually converge after a couple of layers.

Asmitaa Samaadhi: “I am-ness” Samaadhi

By the time we get to Asmitaa Samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention has gone beyond all the objects of the Universe. Everything in the Yogi’s experience has been involuted into Prakriti, and is seen as nothing but a dance of Prakriti in various special modifications.

However, there is still one aspect left.

In Vitark and Vichaar Ssamaadhi, the Yogi’s attention rested upon the Graahya - the objects of knowledge.

In Aanand Samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention rested upon the Grahana - the instruments of knowledge.

Here, in Asmitaa Samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention rests upon the Graahya - the knower itself.

Normally, we think that “I” am the knower. For example, if we are doing a simple noting practice, we may find that we unconsciously give special status to the one who notes various sensations and thoughts. Similarly, when we are doing Dhaaranaa, if we notice carefully, we will find that we are giving a special status to the thought that notices when the mind has wandered.

This special status is the status of Asmitaa - literally, “I am-ness.”

In Asmitaa Samaadhi, the Yogi’s attention turns to this feeling of “I am-ness”, and uses it as a support upon which to rest their Awareness.

Specifically, the object - the aalambanaa - is called the chidaabhaasa (literally the Phantom Consciousness, or the Reflected Consciousness).

A traditional example compares the chidaabhaasa to a reflection of the moon in a pot of water. In this example, the pot is the body, the water is the mind (specifically the sattvic aspect of the buddhi), and the reflected moon is the feeling of being aware. In Yogic terms, the moon which is reflected is the Purusha - the Self.

Truth-bearing wisdom and the “other Samaadhi”

When we “see” our own reflection in the sattvic aspect of the buddhi, it is a sort of shock. We Realize that the feeling of awareness in the mind is not the ultimate conscious entity, and that the “I” is transcendent - beyond the body and mind. When this is repeated, samskaaras start to form in the mind which make this realization sit deeper and deeper, until it eventually becomes the normal way in which the world is seen.

In addition, the fact that the higher Samaadhis are all nirvikalpa (ie. without word and categorization), the mind becomes habituated to parapraktyaksha (ie. the higher perception). Said another way, the Yogi no longer sees the world through a veil of thought, and sees everything as it is.

This habituation to Parapratyaksha is known as ritambhara prajnaa - literally “truth bearing wisdom.”

The reason for this name is that all words and categorizations are essentially symbols - different from Reality, and easy to confuse with it. When names and categorizations are removed, all that is left is the raw Reality, or truth.

Words and categorizations obscure Reality, creating, in a sense, a layer of falsity. When the Yogi’s mind is habituated to parapratyaksha (no words, no categorizations), all that is left is truth. This is why it is known as the “truth-bearing wisdom.”

This experience comes with three side-effects:

The visceral experience that the “I” is not the ultimate conscious entity.

The visceral experience of reality as it is, without the veil of thought.

The visceral experience of the suffering of others, and an intense sensation of compassion.

This third piece - intense compassion - comes from the principle behind the Brahmavihaaras.

As a brief recap, the four Brahmavihaaras are attitudes that the Yogi intentionally cultivates as a preliminary practice. However, in truth, they are the natural state. For example, when we see suffering, we may feel angry, sad, irritated, overwhelmed, and so on. However, if we intentionally cultivate compassion, the mind will come to a state of calm.

Now if we take a moment to notice, we will find that the mind automatically tends towards compassion, and that any other mental state that arises in the face of suffering is a direct result of a veil of thought between us and the perception of suffering.

That is, when we touch suffering directly, without a veil of thought, compassion naturally arises.

This is also true for the other three Brahmavihaaras of friendliness, gladness, and equanimity, with their respective causes.

Now compassion is specifically called out here because it arises as a result of direct contact with dukkha.

At this stage, two causes have arisen for the Yogi - first, they see that all living beings suffer, since they have acknowledged the universal nature of dukkha; second, the mind has become habituated to seeing things without the veil of thought (aka parapratyaksha).

As a result of these two causes, the Yogi’s mind overflows with compassion for all beings everywhere.

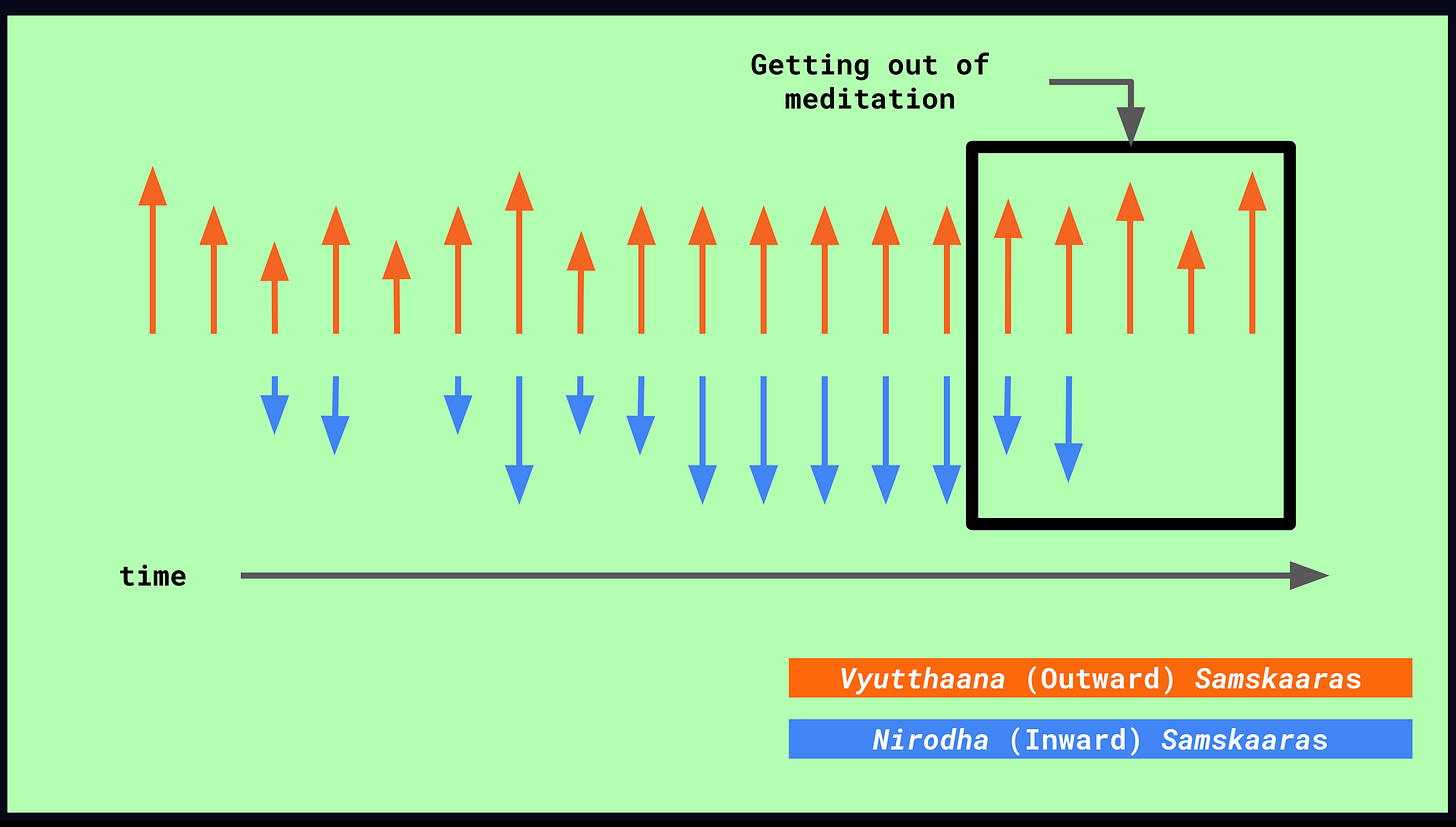

Prajnaa produces nirodha samskaaras

This wisdom, seeing the world without words and categorizations, results in a deepening and creation of more nirodha (inward) samskaaras, thus creating a virtuous cycle. Nirodha samskaaras help to generate and deepen Samaadhi, and so Prajnaa arises. This Prajnaa then generates more nirodha samskaaras, and so the cycle continues. Furthermore, every time the cycle goes around, the nirodha samskaaras get increasingly more nirodha.

Said another way, the mind is not actually attracted to objects, but rather to the names and categorizations that we have layered over the objects. Without name and categorization, all objects - gross and subtle - are all just beautiful movements in the great dance of Prakriti.

Paravairaagya leads to the “other” Samaadhi

The more the Yogi becomes habituated to parapratyaksha - perception without name or categorization - the less their hankering for objects (ie. the more their vairaagya, aka ability to “let go”).

Eventually, vairaagya becomes so intense that perceptions do not leave any samskaaras whatsoever. This “empty” samskaara is known as Paravairaagya - the higher vairaagya, where vairaagya itself is let go of.

When there are enough of these Paravairaagya Samskaaras in the mind, the Yogi’s Awareness is able rest without any support at all, free and independent.

This state is known as Asamprajnaata samaadhi, Nirbeeja samaadhi, or simply the “other” Samaadhi.

The three transformations, and the inner workings of Samaadhi

Samaadhi, and indeed all of Yoga, has its basis in three fundamental transformations. The word “transformation” can often conjure the image of some psychedelic experience - this is not what this is. Rather, these are simply three axes upon which the Yogi’s mind shifts, over time, and with sustained practice, so as to become “fertile ground” for Samaadhi to occur.

The three transformations are:

Samaadhi Parinaam: The Samaadhi Transformation

Nirodha Parinaam: The Mastery Transformation

Ekaagrataa Parinaam: The One-Pointedness Transformation

The first two - Samaadhi Parinaam and Ekaagrataa Parinaam - are perhaps best understood together.

Samaadhi Parinaam is the movement of the mind from all pointedness to one pointedness. That is, when shifts its tendencies from scattered to being focused, this movement is known as Samaadhi Parinaam.

Next, Nirodha Parinaam is the movement of the mind from outward to inward. That is, when the mind shifts its tendencies from things which are more externalized (ie. vyutthaana samskaaras) to more internal (ie. nirodha samskaaras), this is known as Nirodha Parinaam.

These two transformations go together in a sort of 2 x 2 matrix. Take a look at the table below for examples:

The third transformation, Ekaagrataa Parinaam is along the axis of time. Specifically, when the mind becomes prone to having the exact same pratyaya arise in the mind repeatedly and consecutively, this transformation is known as ekaagrataa parinaam.

Said another way, this transformation shows us that what we think is “focus” during Samaadhi - and really any time we focus at all - is not actually holding the mind on the same object. Rather, it is allowing identical pratyayas to appear one after the other, creating the illusion of focus.

Together, we see how Samaadhi actually happens within the mind of the Yogi. At first, the samskaaras become increasingly nirodha, or inward. This can be directly felt during your practice as you settle down into your Aasana, settle the mind through Praanaayaam, and eventually become internally quiet in meditation. Then, you can notice how the mind becomes quieter and quieter - ie. increasingly nirodha (aka Nirodha Parinaam).

The mind may still be moving, however - this is where Samaadhi Parinaam comes in - tying down the roaming mind with various aspects of the aalambanaa, eventually slowing it down to a single spot.

Here, Ekaagrataa Parinaam ensures that the same exact pratyaya is repeating in the mind, until eventually the attention penetrates to the subtle layers of the object, through the various levels of the Tattvas.

When vyutthaana and nirodha samskaaras cancel each other out, there is a level of quietude in the mind - it feels like there are no thoughts. This is nirbeeja samaadhi. The samskaaras are still there, just cancelling one another out.

Eventually, the vyutthaana samskaaras overpower the nirodha samskaaras, and this results in the mind and body returning to the world, and the Yogi coming out of meditation. These are the inner workings of Samaadhi.

The Raincloud Samaadhi and breaking through avidya

All this practice of Samaadhi eventually leads to a breakthrough, where the Yogi sees the entire Universe as nothing but a collection of pratyayas.

If our perceptions, imaginations, etc. (ie. vrittis) are like images on a screen, pratyayas are like the pixels. They are the momentary bursts that we group together and give meaning to.

In reality, everything you experience around you is just a giant Rorschach plot that we have all collectively agreed to interpret in a particular way. This blind faith in the collective understanding is known as avidya, and is the fundamental cause of all our suffering - of dukkha.

This breakthrough, where the Yogi sees the entire Universe as the pratyayas that they are - is known as Dharma-Megha-Samaadhi (literally “the Samaadhi of the Raincloud of Virtue” and/or “the Samaadhi of the Raincloud of fundamental characteristics”)

This clear vision leads the Yogi to see directly through the final veil of avidya - noticing the Reality for what it is.

There is no body, no mind, no self. There is no one to suffer, there never was, and there never will be.

It is this very vision that leads to Kaivalyam - Enlightenment, Freedom, and the final cessation of suffering.

Here, the Yogi has achieved everything that life has to offer, has known everything that is to be known, has done everything that has to be done. There is nowhere to go, nothing to do.

Conclusion

This article concludes our singha-avalokana-nyaya - the Lion’s Backward Glance. We have now reviewed the entirety of the process of Yoga, from the beginning - the acknowledgement of dukkha - to the end - the cessation of dukkha.

It can be tempting to learn about this as a philosophy, or as an intellectual exercise. After all, it is all quite interesting, and it is about the most fascinating thing in the whole world - You.

However, the power of Raja Yoga comes not from philosophy, but from practice.

This is not true for all the four Yogas. For example, reading and studying Jnana Yoga is the practice, or simply listening to stories and developing love counts as Bhakti Yoga.

However, Raja Yoga is utterly useless if studied but not practised. In fact, it is far better to practice without studying than to study without practice.

“One ounce of practice is worth a thousand pounds of theory.”

- Swami Vivekananda

Given this, if you feel attracted to Raja Yoga, spend some time with the preliminary techniques, getting comfortable with them. There is no rush, but if you are in a rush, simply practice intensely and frequently. Eventually the rush will disappear.

Practice every day, and use your life as an opportunity to practice. Difficult situations are gifts provided for you to strengthen your practice of Yoga.

Become good at finding the right technique for the right situation. Then practice meditation every day, and start to notice the effects on your life.

Raja Yoga does not require blind faith, but shraddha, born of direct experience. This shraddha leads to vigour. This vigour leads to mindfulness of all actions in day-to-day life, which then depends into the practice of meditation and Samaadhi. Eventually, Samaadhi leads to wisdom, which results in freedom from suffering.

उत्तिष्ठत जाग्रतप्राप्य वरान्निबोधत।क्षुरस्य धारा निशिता दुरत्ययादुर्गं पथस्तत्कवयोवदन्ति॥Uttishtata jaagrata raapya varaannibodhata kshurasya dhaaraa nishitaa duratyayaa durgam pathahTatKavayoVadantiArise! Awake! Stop not until the goal is reached! The path is sharp like a razor’s edge, the poets say it is difficult to traverse.

- Katha Upanishad, 1.3.14

What now?

For the next few weeks, I will be addressing questions that have been submitted to the form at the button below.

If you would like your question to be answered in this newsletter, feel free to submit it here. If you would like your question to be answered, but not in the newsletter, you can also submit it but just note that you would prefer a private response.

After some Q&A, at some point, we will most likely make a transition to Jnana Yoga - specifically using the framework of Advaita Vedanta.

As always, if you have any thoughts, feedback, questions, or ideas, please do not hesitate to reach out directly via email (by responding to this one), by submitting a question at the button, or my anonymously posting at r/EmptyYourCup.

Thank you for your readership, and may you become free from suffering in this life itself.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti