The Bliss Samaadhi

Aananda Samaadhi: Absorption in the instruments of knowledge

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Once, a soldier came home from war to his farm by the sea. Upon returning to the village, he found that while he was gone, a cyclone had ripped through the village, bringing sea-water with it, making the land infertile, and destroying the homes with it. Many had left the village in search of greener pastures, while a few stayed behind to rebuild. Distraught, he found himself in a bar at the edge of the village, and tried to drink his misery away.

As he drank, he overheard a conversation between two old men. They spoke of a hidden treasure on a faraway mountain, guarded by a great beast. Sipping on his drink, the soldier began to imagine what it would be like to have the treasure. Perhaps he could buy another piece of land to farm, and a new house. Or, if was worth enough, perhaps he could buy enough land for everyone left in the village! He then thought about how he certainly had the military training needed to make the journey and fight the beast.

Resolved to find the treasure, he went up to the old men and asked for more detail. Happy to be listened to, the old men told him the path to the mountain, the beast, and the treasure.

The next morning, the soldier began his journey to the mountain. Days went by, then weeks, and finally he arrived at the foot of the mountain. Looking up, he saw that the peak was hidden amongst the clouds. Strong-willed as we he was, he began the upward climb. Day turned to night, and he found a flat piece of rock upon which to rest. As the sun returned, the soldier arose and continued relentlessly on his upward journey. This cycle continued for several days until he finally reached the top of the mountain, where he saw a great beast at the opening of a cave. The beast was the height of ten men, with teeth as thick as tree trunks, and claws like knives. As he approached, the beast lifted its head, let out a roar shook the very ground, and released a spiral of fire into the clouds. The soldier was afraid, but his determination took over, and he channelled his entire focus to killing the beast. He charged towards the beast, and an epic battle ensued. The beast would breathe fire and swipe its knife-like claws, and the soldier would dodge and parry with his sword. The beast would try to clamp its jaws around him, but the soldier was too quick, and the beast would narrowly miss. The sun set and rose again, and the battle continued - the soldier’s focus was so intense that the beast could not grasp him.

Finally, on the third day, the soldier managed to strike the final blow. He came up underneath the beast and pushed his sword into its jaw. As the beast breathed its last, the soldier lay down in the cave, delighted that he had managed to slay the creature. After a brief rest, ecstatic about his victory and excited to tell the world, he began his downward journey.

In the delight of his victory, he had completely forgotten about the treasure.

Over the past several weeks, we have been discussing the various levels of Samaadhi - the eighth and final limb of Yoga.

Samaadhi begins with Dhaaranaa, or concentration, where the mind is brought to an object - any object - and returned gently back to it when attention wanders. Eventually, attention “sticks” to the object - this is called Dhyaan, or meditation.

Finally, the distinction between observer and observed begins to dissolve. This is Samaadhi.

The process of Yoga is a stepwise, systematic, involution towards the Self. It begins with the outer layers of one’s being - external interactions, then personal conduct, then the body, the breath, the senses - and finally arrives at the mind.

The process of Samaadhi is like a fine-tuned version of the same involution.

This can be compared to tuning a violin. At first, the pegs are tuned to get the notes close to their proper place. Then, the fine-tune knobs near the chin-rest are rotated ever so slightly to get the notes to their perfect pitch.

The basic method of Samaadhi is to systematically work our way from the external world towards the Self, seeing grosser objects as effects of their subtle causes, and in turn seeing the subtle causes as effects of even subtler causes, until we can go no further.

P: What are the gross effects and subtle causes? Can you be more specific?

It begins with the objects of the world - this could be the breath, a sound, a flame, or anything that you can perceive. It is then broken down into its subtle components - the tanmaatraas (ie. sound, texture, form, etc.). For more on this stage, take a look at this article:

These tanmaatraas are then seen as effects of their subtler cause, the ahamkaar (ie. the “I-maker”), which is further seen as an effect of its subtle cause, the buddhi (ie. the intellect). Finally, the buddhi is seen as an effect of Prakriti (aka the three gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas). More here:

But that’s not all.

The map for Samaadhi is known as the 25 Tattvas. This is a phenomenological framework through which we can view the entire Universe, breaking it down into 25 categories of experience.

This can be thought of as a tree.

From a distance, it is easiest to see the mass of leaves. When we come closer, we can see the branches and the trunk hiding beneath the canopy. Then, if we dig underground, we see the roots, which are unseen unless you know where to look. Finally, through inference, we can understand that the tree sprouted from a seed.

Similarly, viewing the 25 Tattvas in this way, the easiest thing to see are the gross objects in the world - particular sounds, tastes, textures, and so on. These are like leaves on each branch.

If we look a little more closely, we see that the particular sounds are just modifications of unmodified sound (ie. the tanmaatraa of sound), the particular textures are just modifications of unmodified texture (ie. the tanmaatraa of texture), and so on. These are like branches on the tree.

If we dig a little deeper, we see that all of the tanmaatraas are just modifications of the same ahamkaar. This is like the trunk of the tree.

Next, when we dig underneath the surface, we see that the ahamkaar is just a modification of the buddhi.

Finally, we can figure out, by inference, that the buddhi is just a product of the gunas - Prakriti in flux.

However, the tanmaatraas are just one set of branches. If we look closely at the diagram, we will notice that there are three more branches stemming from ahamkaar - the manas, the karmendriyas, and the buddhendriyas (aka the jnanendriyas).

P: What are those?

The three branches of ahamkaar

Ahamkaar evolves into three aspects - a sattvic aspect, a rajasic aspect, and a taamasic aspect. If you missed the article on the gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas - you can find out more here:

In a sense, it can be compared to the trunk of a tree with sixteen branches - five of the branches hang low to the ground, five of them are in between, and five branches point upwards toward the sky.

The five lower branches are the five tanmaatraas - these are the taamasic evolutes of ahamkaar.

The five middle branches are the five karmendriyas - the organs of action. These are the raajasic evolutes of ahamkaar.

Next, the six upper branches are the five buddhendriyas - the sense organs - as well as the manas - the doubting, dithering mind.

While Vitark and Vichaar Samaadhi deal with the taamasic evolutes of ahamkaar, Aanand Samaadhi brings attention to the sattvic evolutes.

P: What about the rajasic evolutes? The karmendriyas?

Jogi: Traditional commentaries do not spend much time here. However, for our purposes it can be considered to be a sort of transition stage between Vichaar and Aanand Samaadhi.

Let us briefly cover these aspects.

Karmendriyas: The powers of action

The word karmendriya is a combination of the words karma (ie. action) and indriya (ie. power). They are the powers of action. In order of increasing subtlety, they are:

The power of excretion

The power of procreation

The power of movement

The power of grasping

The power of speaking

These are not the physical organs, but the mental powers that underpin their functioning. That is, if you are walking in a dream, or in your imagination, you are still using your karmendriyas.

Notice when you look at an object, the word for it flashes in your mind. This is the karmendriya of speech.

If you look closely, you will also notice the other relevant organs of action at play. For example, if it is a road, there will be a subtle imagination of movement. If it is a physical object, there will be a subtle imagination of grasping.

For musicians, you may notice this when you see your instrument in front of you, or when you listen to a song where your instrument is playing. If you notice closely, you can feel a subtle mental movement where the fingers are adjusting according to the music.

For those who play a sport, you may notice the same thing when you watch the sport being played. This is the karmendriya coming up along with the loka-pratyaksha (the regular, non-Samaadhi perception).

They appear and disappear together.

Just like the Play-doh figure is a modification of Play-doh, or like a wave is a modification of water, the karmendriyas are a modification of the ahamkaar with a preponderance of the rajas guna - the quality of movement and activity.

Although it is not often mentioned in traditional commentaries, this can be considered the transition stage into Aanand Samaadhi. That is, the attention is brought to rest upon these powers as modifications of the ahamkaar, then it is brought upon the ahamkaar as a modification of the buddhi, and finally upon the buddhi as a modification of Prakriti.

At this point, the tamasic and rajasic evolutes of ahamkaar have been probed with the fine-tuned attention of Samaadhi. Here, the Yogi brings their attention to the sattvic evolutes of the ahamkaar, and then involutes them back to Prakriti as before.

P: What are the sattvic evolutes of the ahamkaar?

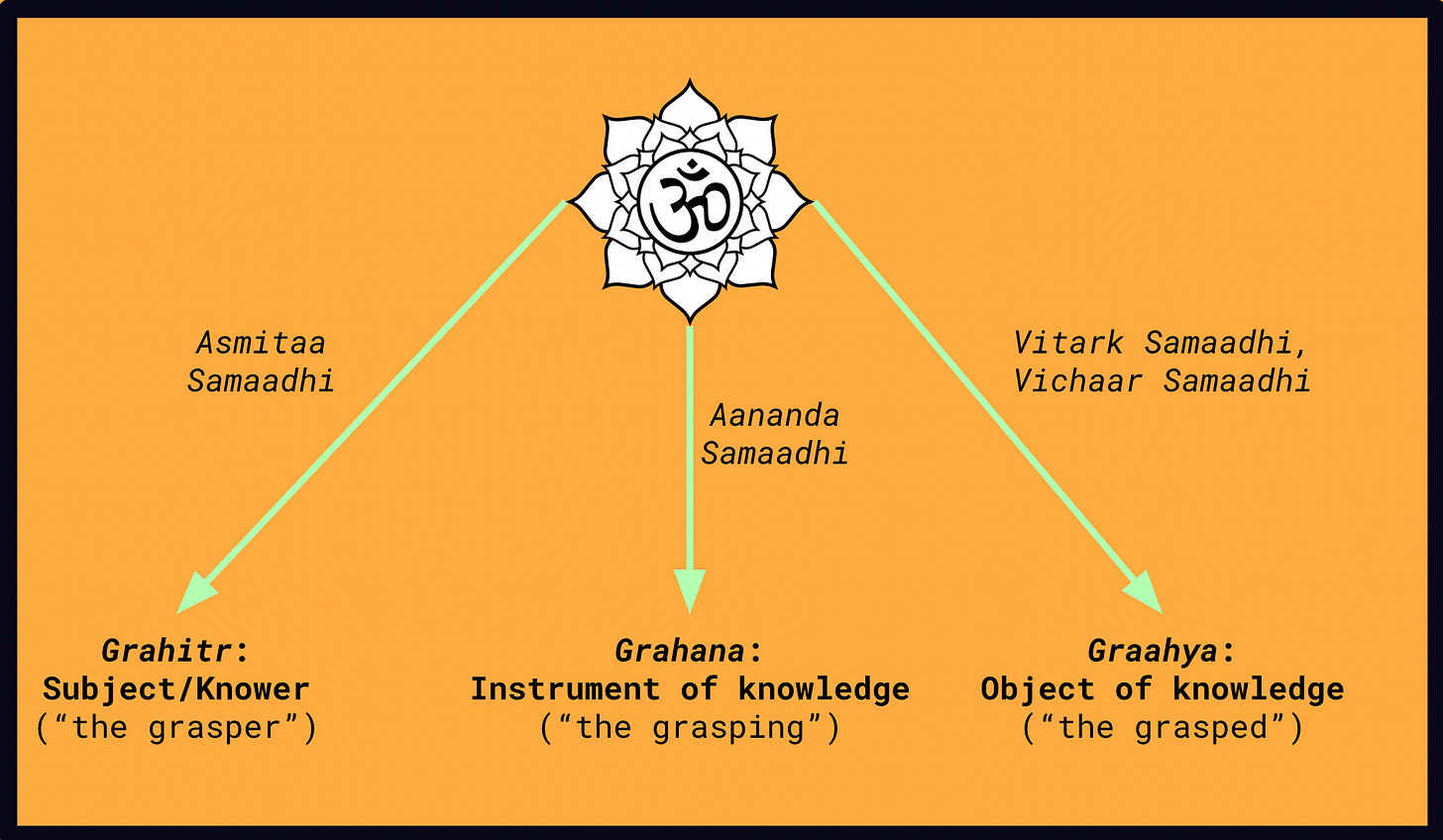

Jogi: The buddhendriyas and the manas. These are the instruments of knowledge, or the grahana.

Manas: The dithering mind

The manas is the power of movement of attention - the reigns of the horses in a chariot. This is what connects the senses to the intellect. You can feel the manas when we cannot decide between two things, and the mind flits between the options.

This “flip-flopping” mind is called manas, and is defined as:

मनो नाम संकल्पविकल्पात्मिकान्तःकरणवृत्तिः।Mano naama sankalpaVikalpaAtmikaAntahkaranaVrittihManas is the name of that modification of the internal instrument which [dithers between] one option and another.

- Vedantasara, 66

The manas interacts with the senses, and presents their objects - both physical and mental - to the buddhi. Additionally, the buddhi directs the manas, through the senses, towards objects that have been decided by it.

The manas is responsible for doubting or dithering between options, but also for emotion, and stoking inner vocalisations and other inner sensations.

Whenever you cannot decide between two things - which show to watch on Netflix, what aalambanaa to use for meditation, or what to eat for dinner - know that it is the manas at play.

Just like the Play-doh flower is a modification of Play-doh, or like a wave is a modification of water, the manas is a modification of the ahamkaar, which is, in turn, a modification of the buddhi.

Buddhendriyas (aka Jnanendriyas)

The buddhendriyas, or jnanendriyas (organs of knowledge), are the five powers of perception. In order of increasing subtlety, they are:

The power of smell

The power of taste

The power of sight

The power of touch

The power of hearing

Just like the organs of action above, these are not the physical organs themselves, but rather the mental powers that underpin the ability to sense in these five ways.

Just like the Play-doh flower is a modification of Play-doh, or like a wave is a modification of water, the buddhendriyas are five different modifications of the ahamkaar with a preponderance of the sattva guna - the quality of clarity, knowledge, and lucidity.

If we look closely, we will find that any perception - internal or external - cannot exist without these powers. For example, there cannot be a sight-perception - in your mind or externally - without the power of sight.

Similarly, there cannot be a sound-perception - in your mind or externally - without the power of hearing.

This understanding is critical: Both arise and fall together in pairs - when one is, the other is; when one is not, the other is not.

The three branches are interdependent

The tanmaatras, the karmendriyas, and the buddhendriyas are all composed of ahamkaar. They are like branches that are connected at the trunk, but are vast enough to seem like separate trees altogether.

In Vichaar Samaadhi, discussed last week, the aalambanaa (e.g. breath) is seen as the tanmaatraas of texture and sound, which are in turn seen as modifications of the ahamkaar, which is seen as a modification of the buddhi, and so on.

Here, in Aananda Samaadhi, the Yogi’s goes to the powers of touch and hearing - the instruments of knowledge - which are also seen as modifications of the ahamkaar. That is, both the tanmaatraas and the senses organs are modifications of the very same underlying substance!

Said another way, touch and texture are actually the same thing, with slight variations in their modification. Similarly, sound and hearing are the same thing, with slight variations in their modification.

P: How can you say they are the same thing?

Jogi: Texture and the sense of touch are interdependent. Without the sense of touch, there is no texture, and without texture, there is no sense of touch. Without the sense of hearing, there is no sound, and without sound, there is no sense of hearing. It is a two-way relationship - one depends on the other for its existence, and they cannot be shown separately from each other.

P: What about in a sensory deprivation tank? I have a sense of hearing, but there is no sound.

Jogi: How do you know you have a sense of hearing, or if it has been removed?

P: Because I can hear before and after the sensory deprivation.

Jogi: Imagine a situation where I could wave a magic wand and remove your sense of hearing. Now imagine one scenario where I put you into a sensory deprivation tank, and waved the magic wand to remove your sense of hearing, and a parallel scenario where I did not wave the magic wand. How can you tell one from the other?

P: I cannot.

Jogi: Exactly. There is no indication of the existence of the sense of hearing apart from sound.

P: Ok, but how does that imply that it doesn’t exist? It could be that it exists, or it could be that it doesn’t?

Jogi: What do we mean by a sense of hearing, unless there is sound?

P: That the capacity is there in case a sound occurs.

Jogi: This implies continuity, but there is no evidence of continuity.

P: What do you mean?

Jogi: Can you show me the past or the future?

P: No. The past is a memory, and the future an imagination. These do not exist in reality, only in concept.

Jogi: Exactly.

P: Ok, but what does that have to do with my sense of hearing?

Jogi: Continuity being only conceptual, the sense of sound as a “capacity” in the absence of a sound is also only conceptual. In this way, the sense of sound as a capacity cannot be shown to exist outside of thought.

Sound and the sense of hearing are the same - two sides of the same coin. The coin is ahamkaar, and the material from which it is made is buddhi. The same logic can be applied to the karmendriyas and their respective objects.

Said another way, we don’t actually experience sound through a sense of hearing. What we experience is the contact between sound and the sense of hearing. This is true for all the senses.

We never actually experience the senses on their own, or the objects on their own. We only ever experience these point-like “contacts”, and then presume that there are two independent sides to it, confused as we are by the variety of sense experience.

Through Aanand Samaadhi, we come to see this clearly, for ourselves. The world begins to appear like a constellation of these “contacts”, rather than as objects - mental or external - perceived by sense organs “owned” by a “self.” Specifically, taking the example of the breath as the aalambanaa, the checkpoints on the journey look something like this:

The mind is brought to rest upon the breath. When it wanders, it is returned to the breath.

The mind sticks to the breath.

The distinction between observer and breath disappears, and the breath alone shines.

The breath is seen without the name “breath” or the knowledge (ie. categorizations) into “inhale”, “exhale”, “breathing”, “soham”, “hamsa”, etc.

The breath is seen as nothing but the tanmaatraas of texture and sound.

The tanmaatraas of texture and sound are experienced without the name or knowledge.

Texture and sound are seen as interdependent with the senses of touch and hearing. For example, rather than texture sensed by touch, it is seen as a singular contact of texture-touch.

Texture-touch and sound-hearing are seen as interdependent with manas.

Texture-touch, sound-hearing, and manas, are seen as nothing but the ahamkaar.

The ahamkaar is seen as nothing but the buddhi.

Buddhi is seen as nothing but Prakriti.

When this happens, the feeling of continuity of mind and self begins to drop away. Like the other Samaadhis before it, it can be accompanied by a sense of fear. However, when this fear dissipates, a deep sense of bliss permeates the entire body and mind. Additionally, every sense perception is experienced as extremely blissful in itself - like the feeling one gets momentarily when listening to the sound of the waves, or the moment one first glances at a beautiful view. This deep feeling of bliss is where this stage of Samaadhi gets its name - Aananda.

However, there is a danger in this bliss.

Like any other sensation, it is impermanent and non-self. However, since it is such a deep meditative state, due to the fact that we spend a lot of time and effort getting to it, and because we have heard that the final stage of Awakening is associated with Bliss, we can easily confuse this state for the final goal.

Just like the soldier in the story at the beginning of this article, we have spent so much effort and attention on overcoming the obstacles, we run the risk of forgetting all about why we began our journey.

तत्र सत्त्वं निर्मलत्वात्प्रकाशकमनामयम्।सुखसङ्गेन बध्नाति ज्ञानसङ्गेन चानघ॥Tatra sattvam nirmalatvaatPrakaashakamAnaamayamSukhaSangena baddhnaati gyaanaSangena chaAnaghaAmong these [three gunas], sattva, being the brightest, is illuminating and free from pain.

O Innocent One, it binds [the Yogi] through attachment to knowledge and attachment to bliss.

- Bhagavad Gita, 14.6

Until next time:

Notice the action of your manas in day-to-day life.

Notice the interdependence between senses and their objects. That is, rather than seeing objects “through” your senses, try to shift your perspective to being aware of the constellation of individual “contacts.”

Take notes to see how this affects your daily meditation practice.

Ask questions here!

Next time: Phantom Consciousness