The illusion of "focus"

Ekaagrataa Parinaam, and the world in slow motion

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

P: In Nirbeeja Samaadhi, and even when the mind is completely focused on an object within Sabeeja Samaadhi, the mind is completely still. Is it not?

Jogi: In a manner of speaking, yes.

P: But the mind is made of Prakriti - the three gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas - right?

Jogi: That’s right.

P: The three gunas are always in flux, right? Never still for even a moment?

Jogi: That’s correct.

P: Then how is it possible for the mind to be completely still?

The question from our friend P, as usual, is a deep philosophical objection levelled against the Yoga school by a number of other schools of Indian philosophy.

To summarize - the mind is made of the gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas - which are always in flux, never still for even a moment. However, it seems as though the final limb of Yoga - Samaadhi - is described as a state of complete mental stillness.

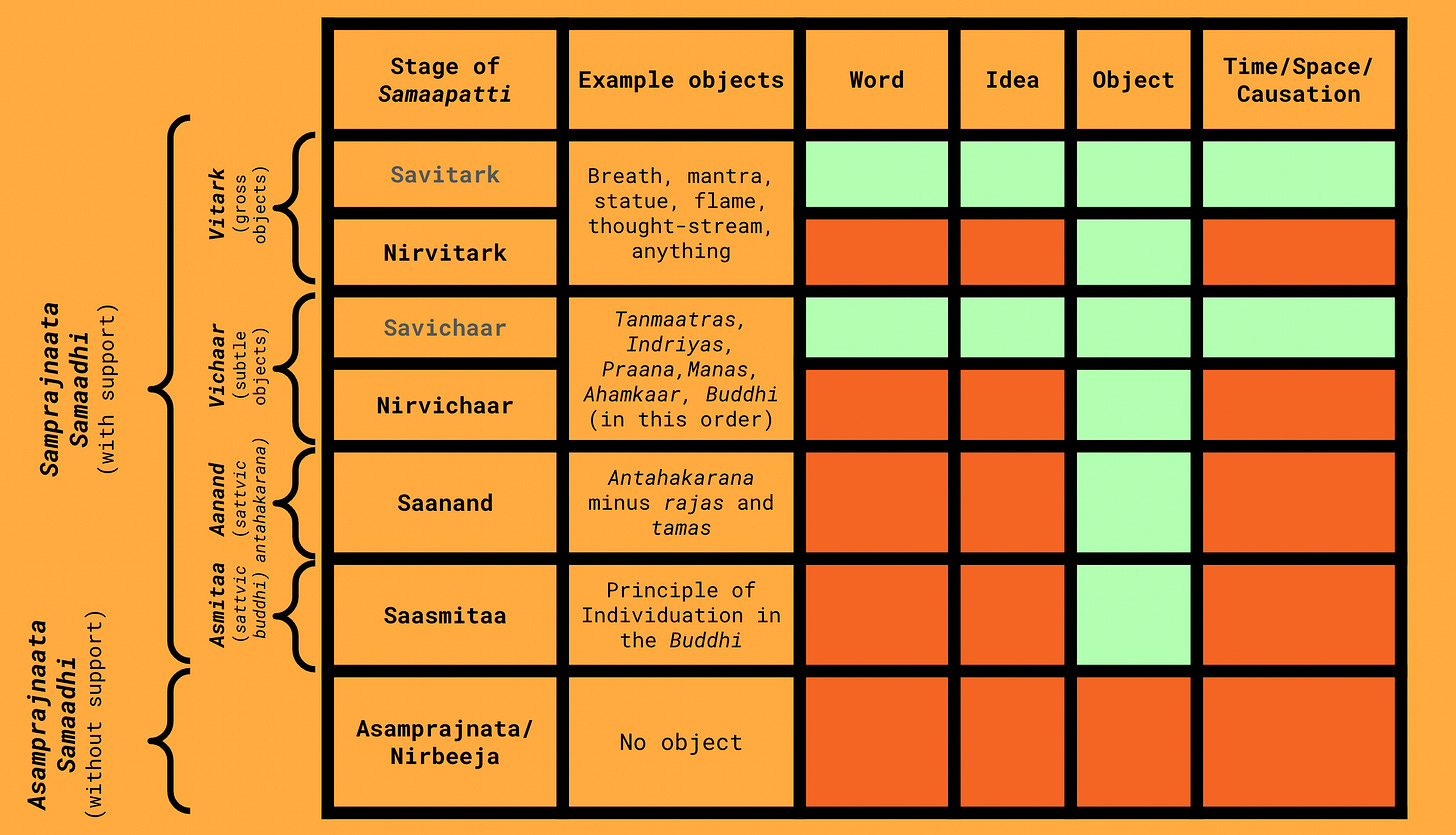

Samaadhi is of two forms - sabeeja, or “with seed”, where the mind is absorbed completely in an object of focus (called the aalambanaa, or support); and nirbeeja, or “without seed”, where the mind is completely still of all mental movements, without any support for attention.

If the mind is ultimately made of the gunas, which are always in flux, it seems that any type of Samaadhi, or even of focus, should be impossible.

Yet, we find in our experience, that it is indeed possible.

We all have the experience of being entirely focused on something, of attention not wavering for even a moment.

For those of us who have been meditating for some time, this experience is perhaps even more frequent and intense, and so this objection should be cause for concern.

After all, it seems as though the underlying philosophy is at odds with our direct experience.

Ekaagrataa Parinaam: The One-Pointedness Transformation

ततः पुनः शान्तोदितौ तुल्यप्रत्ययौ चित्तस्यैकाग्रतापरिणामः।Tatah punah shaantaUditau tulyaPratyayau chittasyaEkaagrataaParinaamahThere, when similar pratyayas rise and pass consecutively in the mind, this is called Ekaagrataa Parinaam (the One-Pointedness Transformation).

- Yoga Sutra, 3.12

The mind is never static - even for a moment. After all, the mind is made of gunas which are always in flux. Yet, we have the experience of being focused.

How is this possible?

Consider a reel of film.1 The illusion of movement is created by different frames in the reel being slightly different from each other. If a film-maker wanted to create an illusion of stillness, they would place identical reels one after the other. This way, while the reel keeps rolling, the image on the screen will remain static.

Ekaagrataa, or one-pointed focus, is much like this.

When we focus on an object, while it may feel as though the mind is still, what is actually occurring is a steady flow of consecutive near-identical pratyayas, generated from near-identical samskaaras that sprout one after the other.

Then, when a different samskaara arises as a pratyaya in the mind, we experience what we call a “break” in focus.

In reality, however, the mind was never still, for even a moment.

When consecutive similar pratyayas arise in the mind, we experience this as one-pointed focus, and this is known as the Ekaagrataa Parinaam, or the One-Pointedness Transformation.

However, ultimately, we find that the idea of “focus” - holding on to a single thought - was an illusion all along.

The illusion of thought

Samskaaras, or tendencies, are like seeds in the mind. These samskaaras sprout into pratyayas, which, when grouped together, are experienced as thought patterns - called vrittis.

Samskaaras, as we have discussed at length, are generally of two types - vyutthaana (outward), and nirodha (inward).

These two types of samskaaras counteract each other. When the vyutthaana samskaara outweighs a corresponding nirodha samskaara, the result is a conscious thought, word, or action. On the other hand, when they are completely balanced, or if the nirodha samskaara is stronger than the vyutthaana samskaara, the Yogi experiences this as a state of emptiness, although there is ongoing movement beneath the surface of awareness.

Each samskaara also has some content. For example, you can have a samskaara about attraction towards a particular type of food, or you can have a samskaara about aversion to a particular kind of smell.

The content of these samskaaras can also be more complex.

For example, you can have a samskaara that will sprout as an aversion to a particular person speaking to you in a particular way in a particular place, or a samskaara that will sprout as a fear of heights, but only when you are hungry.

Samskaaras are highly individualized - every person has had their own unique set of experiences, which has left unique traces on their mind. These samskaaras then result in highly specific forms of thoughts, words, or actions in particular situations.

These samskaaras are continuously sprouting into thought from moment to moment. Consider the number of thoughts you have had in the past hour alone!

Focus, therefore, is when samskaaras with the same (or rather, similar) content sprout into similar pratyayas immediately one after the other, for a perceivable period of time. Through focus (ie. when the samskaaras are sprouting into similar pratyayas consecutively), it is easier to see the details of the process of thought.

At first, when we watch the mind, it seems as though many thoughts are happening concurrently. These can be imagined as several different parallel streams of thought.

However, if we watch closely, we will notice that the mind can only really hold one thought at a time. The reason it seems like we have multiple threads going at once is that attention is flitting between the different streams so quickly, that it seems like they are all happening simultaneously. This realization - that the mind can only really hold onto a single thing at any given moment - can provide a great flash of insight.

Said another way, it initially feels like the mind has many vrittis present within it at any given moment in time.

However, when we notice closely, we find that the mind cannot even hold on to a single vritti in a given moment, but rather flits between several pratyayas (pixels of a vritti), and later combines them into a vikalp (imagination) of holding several vrittis at once.

If we truly absorb this, we will find, for example, that there is no sense in trying to multi-task, or that if we have too many things going on in the mind at once it can result in feelings of tiredness or stress. This will then lead to an automatic pull towards eka-tattva-abhyaas.

In a previous article, we had discussed eka-tattva-abhyaas as the practice of focusing on one thing at a time. You can find more on this topic here:

This is a foundational practice in Yoga that can be used to calm the mind and reduce the effect of the nine obstacles and the four accompaniments.

However, at this stage of meditation - once we see that the mind cannot hold multiple things at once, by its very nature - it ceases to be an intentional practice, and we realise that it is the natural way of being.

The next step once we see that the mind is not holding multiple threads, or vrittis, but is rather rapidly flitting between one pratyaya and another, is to notice the rise and fall of each of these individual pratyayas.

These pratyayas do not just appear in full force and disappear completely. Rather, they rise and fall like waves in an ocean, increasing and reducing in intensity.

This rise and fall is so rapid that we normally don’t notice it. However, once we have tuned the attention sufficiently, and are able to sustain focus2 for an extended period of time, we can watch the rise and fall carefully, and see that each of these pratyayas has its own individual life cycle.

This “tuned attention” is sort of like watching a film in slow motion. Where you previously ignored things because they happened so fast, the level of detail can be astounding.

What’s more, we can start to notice that each pratyaya is not actually connected to the other pratyayas. They are completely independent of each other, rising and falling alone. Then, every few moments, another vritti arises to give it meaning in terms of words and ideas.

This feeling can be somewhat unsettling, and can make one feel like everything they have ever known is simply imagined. And, in a sense, this is true.

All the thoughts, words, actions, and events that occur within experience are simply combinations of individual pratyayas which we later group together (using more individual pratyayas). The very “I” that groups these together is also another set of individual, unrelated, momentary pratyayas.

A traditional example compares this to a child who sees a rainbow from a distance, and then tries to come closer to touch it.

The rainbow looks real - it has colour and form, a particular shape and location. It is, in all respects, an object in its own right. However, when the child comes closer to it, they find that it disappears before their very eyes - they cannot grasp it. It is real, but unreal at the same time.

In this way, when we focus the mind and turn it inward, we can see clearly, for ourselves, that the world of objects is ultimately unreal.

What we experience - including our very sense of self - is a collection of “contacts”, or momentary pratyayas in the mind, which rise and fall seemingly of their own accord. We group them by superimposing names and meaning upon them, and then take these names seriously. This a manifestation of avidya - the root cause of dukkha, or suffering.

When we experience this state - known as Dharma-Megha Samaadhi - it results in, and strengthens, Para-Vairaagya - the highest “letting go”, and when this is applied to the kleshas, they become like burned seeds, never to sprout again.

Next time: Dharma-Megha Samaadhi: The Samaadhi of the Raincloud of Dharma

Credit to Prof. Edwin Bryant for this analogy.

The phrase “sustain focus” is simply a figure of speech. As we have seen, focus is not something that comes from holding on to, or sustaining, a thought, but rather is what we call a series of similar pratyayas appearing and disappearing consecutively.