Truth-bearing wisdom: Part II

The world beyond words, the light of compassion

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Last week, we began a discussion on Prajnaa (प्रज्ञा, pronounced pruh-gyaah) - the wisdom that begins to arise in the Yogi’s mind when Nirvichaar Samaadhi becomes stable. If you missed it, here’s a link:

As a brief recap, Nirvichaar Samaadhi is the fourth of the seven samapattis, or levels of engrossment, within the eighth limb of Yoga - Samaadhi, or meditative absorption.

Samaadhi is when meditation deepens to the extent that the distinction between observer and observed begins to disappear. It is not a technique in and of itself, but rather an extension or deepening of the sixth limb, Dhaaranaa. In Dhaaranaa, attention is placed upon an object, and when the mind wanders, attention is gently brought back to the object. This process is repeated until eventually, after sufficient practice, attention “sticks” to the object (also known as the aalambanaa, or support). This is called Dhyaan, or meditation.

Finally, Dhyaan deepens into Samaadhi when the mind has become sufficiently clear of the kleshas, or colourings, and the outgoing tendencies (aka vyutthaana samskaaras) have been overpowered by the incoming tendencies (aka niruddha samskaaras).

In this way, Samaadhi is not something that you do, but rather something that happens to you. All we can do is cultivate fertile ground by practising the earlier limbs, and systematically rooting out the kleshas throughout our day-to-day lives, as well as in meditation.

Within Samaadhi, Nirvichaar begins when the mind becomes entirely absorbed in the tanmaatras, or subtle elements, that compose the aalambanaa. For example, if you are using the breath as your aalambanaa, Nirvichaar begins when the mind becomes absorbed in sound and texture, to the exclusion of all else, including the word “breath” and the categories of “breath”, “inbreath”, “outbreath”, etc.

Said another way, the saamaanyas (ie. generics) are dropped, and the vishesha (ie. specific) remains. To make this clear, let us break it down. With the breath, there are three components:

Shabda: The word “breath”, in the form of the sound of the word - mentally or physically spoken.

Artha: The breath itself, without any layer of thought.

Jnaana: “Breath-ness” - the category of “breath” into which all breaths fall.

In Samaadhi, shabda and jnaana drop away, and only artha remains. In Nirvichaar Samaadhi, it is the same, except on the tanmaatras - ie. the word “texture”, “sound”, or even “tanmaatra” drop away, as do the categories, but the tanmaatras themselves shine alone.

Nirvichaar Samaadhi starts with the tanmaatras, but goes on to its more subtle causes. That is, the tanmaatras are seen as evolutes, or modifications, of ahamkaar, which is in turn seen as an evolute, or modification, of the buddhi, which is, in turn, seen as an evolute of Prakriti (aka the three gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas). At each stage the shabda and jnaana are dropped, and the artha shines alone. If you missed the articles on Nirvichaar Samaadhi, take a look at these three articles for the systematic progression through this level of meditative absorption:

When Nirvichaar starts to become stable, a certain wisdom begins to arise in the mind of the Yogi. This is not some supernatural wisdom where the person starts to suddenly knows everything about everything (although this may certainly happen), but is rather a type of knowledge that is different from the normal kind of knowledge we gain from experiencing the world.

श्रुतानुमानप्रज्ञाभ्याम् अन्यविषया विशेषार्थत्वात्।ShrutaAnumaanaPragyaabhyaam anyaVishayaa visheshArthatvaatPrajnaa (ie. the truth-bearing wisdom gained from Nirvichaar Samaadhi) has a different object than the teachings and logic, in that it has vishesha (specifics) as its object.

- Yoga Sutra, 1.49

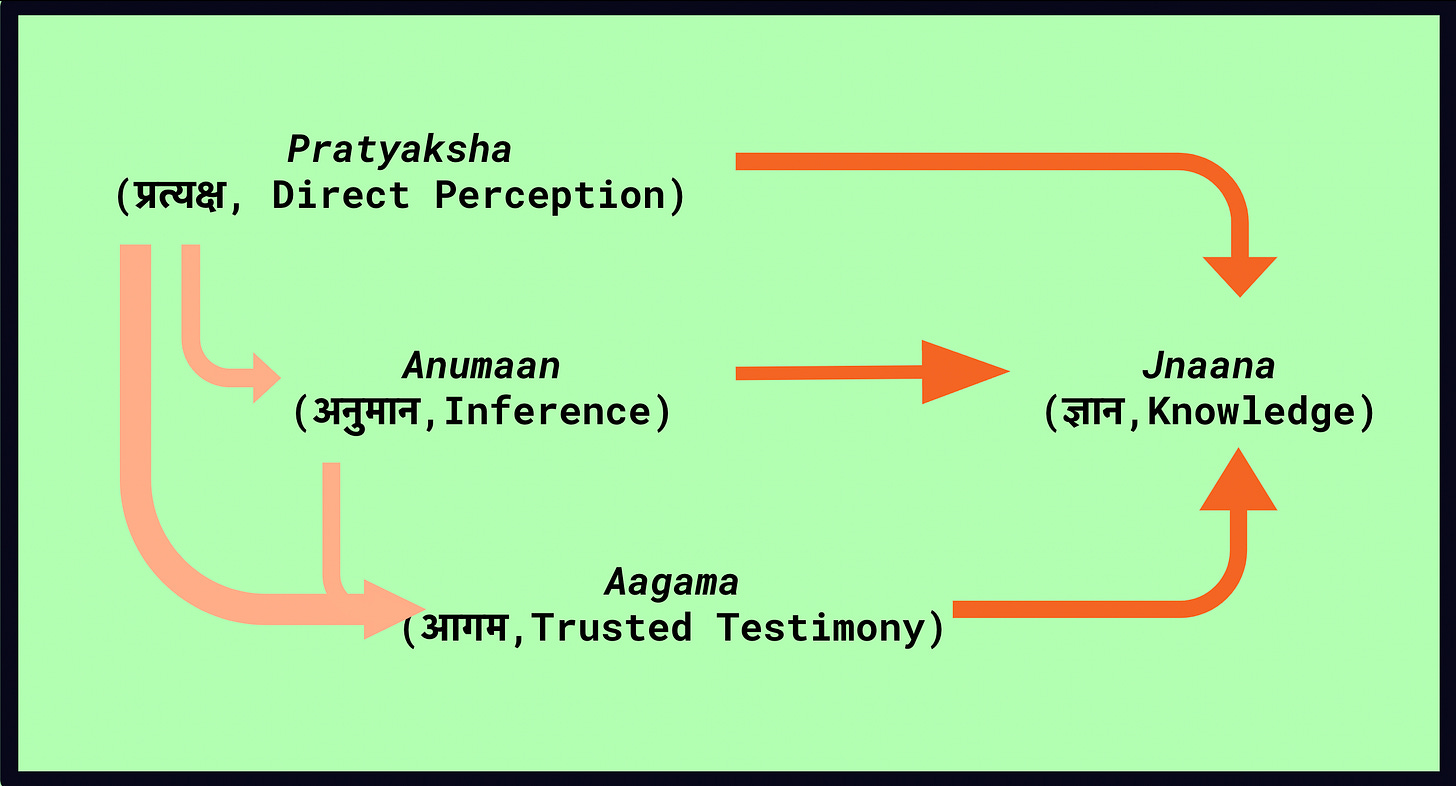

Normally, knowledge comes in three ways:

Pratyaksh: Direct perception

Anumaan: Inference

Aagama: Trusted testimony

Of these three, both inference and trusted testimony ultimately depend upon direct perception. That is, one must directly experience something from which to infer something else, or one must directly experience the words said by another person who has the knowledge, and that person has to have either directly experienced or inferred the object of knowledge in order to impart the knowledge in the first place.

In Yoga, Pratyaksha, or direct perception, is of two types:

Loka-Pratyaksha (aka Apara-Pratyaksha): Regular or ordinary perception

Para-Pratyaksha: The higher perception

The only difference between the two types of perception is that in the latter - Para-Pratyaksha - word and idea are dropped away, and the object (the artha) shines alone. Said another way, Loka-Pratyaksha is limited to knowledge of generics, or saamaanya, whereas Para-Pratyaksha is the knowledge of specifics, or vishesha.

This knowlege of visheshas is a different kind of knowledge altogether, and results in Prajnaa, or wisdom, as a side-effect.

Specifically, this wisdom comes in three forms:

The visceral experience that the “I” is not the ultimate conscious entity.

The visceral experience of reality as it is, without the veil of thought.

The visceral experience of the suffering of others, and an intense sensation of compassion.

Last week, we discussed the first and began a discussion on the second. In this week’s article, we will continue the discussion on the second, and begin discussing the third.

Looking for “me” in the body-mind is like looking for “music” in a guitar.

आगमेनानुमानेन ध्यानाभ्यासरसेन च।त्रिधा प्रकल्पयान्प्रज्ञा लभते योगमुत्तमम्॥The Highest Yoga is gained by cultivating Prajnaa through the threefold practice of studying the teachings, inference/logic, and meditation.

- Unknown, quoted by Vyasa in Vyasabhashyam on Yoga Sutra 1.48

The goal of Yoga, as is true for all soteriological teachings, is the cessation of suffering. Yet, as we practice, it is a common experience for many students to feel “I understand all of this intellectually, but I still suffer.”

For example, we have learned that all apparent pleasures are ultimately dukkha, or suffering. Yet, despite knowing this intellectually, we hanker after pleasures. Or, we have learned and reasoned that the Self is neither the body, nor the mind. Yet, we act as though the body-mind complex is “me”, and get upset or anxious when it is threatened.

Another example, we have learned that the Self is neither the doer or enjoyer of actions - that nature acts of its own accord, and the ahamkaar, a function of mind, takes credit for these actions saying “I did it”, or “This is mine.” Yet, even though we understand this intellectually and can prove it with logic and reason, we act and think as though we are the doers of our actions.

The reason for this is that the knowledge has not “set in” - that is, while the student may know the teachings, and may even have reasoned about them to the point of absolute conviction, the teachings are still be applied at the conceptual level. Specifically, they are being applied at the level of shabda and jnana rather than artha.

When Nirvichaar Samaadhi becomes stable, we are able to apply the teachings (which are also concepts) to the level of artha - the reality as it is - without the layer of concept and thought. As a result, the teachings begin to “set in”, and we are able to clearly see our suffering reduce.

Let us use the example of doership (कर्तृत्त्व, kartrittva) and enjoyership (भोक्तृत्त्व, bhoktrittva).

Right now, more than likely, you feel like “you” are reading this article. You likely also feel that you decided to open it, that you decided to sit where you are sitting, and that you are deciding to continue reading.

However, the “you” that is making the decision is the buddhi - not You. The “you” that is sitting is the body - not You. The “you” that is seeing the words is the sense of sight - not You. The “you” that is scrolling is your karmendriya of grasping - once again, not You.

Yet, somehow it feels like there is a cohesive “me” that is reading this.

Where, one might ask, is this cohesive “me”?

Is it in the fingers? Certainly not.

Is it in the eyes? No, that seems too limited.

Is it in the buddhi? Maybe, but I can clearly notice my buddhi if I watch closely, so that can’t be me either.

So where is it?! Where am “I” in all of this?

If we look closely, with focused attention, using the tool of Samaadhi, we will come to see that no matter where we look, we can’t find it.

There is no “me” hiding somewhere in the body-mind, any more than there is “music” hiding somewhere inside a guitar.

We may understand this intellectually, but can only truly grok this conclusion by systematically eliminating all the possible hiding places.

Specifically, in Nirvichaar Samaadhi, we are progressively moving deeper, layer by layer, through all the possible hiding places, involuting all external modifications into their causes, until everything is seen to be nothing but a modification of Prakriti, which is then also seen to be “not me.”

When this happens, the feeling of doership and enjoyership - kartrittva and bhoktrittva - are seen to be functions of the buddhi, rather than functions of the Self. This leads to a feeling of freedom and peace - like a boatman who realizes that they were rowing for no reason, since the wind was already in the sails, or like a person who realizes they can put down their backpack now that they are sitting in the car.

“Enlightenment1 is like everyday consciousness but two inches above the ground.”

- DT Suzuki

The light of compassion.

प्रज्ञाप्रसादमारूढस्त्वशोच्यः शोचते जनान्।भूमिष्ठानिव शैलस्थः सर्वान्प्रज्ञोऽनुपश्यति॥PragyaaPrasaadamAaroodhasTuAshochyah shochate janaanBhoomishtthaanIva shailasthah sarvaanPragyoAnupashyatiJust as one situated on a mountaintop sees everything situated in the plains, so one with the lucidity of Prajnaa (Yogic wisdom) no longer suffers, but clearly sees the suffering of all beings.

- Yoga Vashishta, 7.102.49

Previously, we discussed the Brahmavihaaras - the four attitudes which form a preliminary technique to calm the mind in stressful situations.

In the initial stages of practice, each attitude is to be intentionally cultivated in particular situations in order to calm the mind. For example, if one experiences the happiness of another person, rather than using thought to stoke the fires of jealousy, anger, greed, or sadness, the Yogi can use thought to stoke the fire of maitri, or friendliness by mentally reciting “May you be well, may you be happy.” As another example, if one experiences someone doing what they consider to be a “bad deed”, rather than using thought to stoke the fire of anger, hatred, righteous indignation, and so on, the Yogi can calm the mind by using thought to stoke the fire of upeksha, or equanimity by mentally investigating the causes and conditions that led them to act in that way.

As a preliminary practice, the attitude is intentionally cultivated in order to weaken the effects of pre-existing tendencies that may agitate the mind. That is, one may have a tendency towards jealousy, and so cultivating gladness when “good” things happen to other people helps to weaken this tendency and bring the mind to a state of calm.

However, as the practice of Yoga deepens, the Yogi will start to notice that the Brahmavihaaras are actually the natural state of mind when confronted with the corresponding situation.

That is, it is not that one needs to cultivate maitri in the face of happiness. Rather, when faced with happiness the mind’s natural state is maitri - it is the layer of conceptual thought that gets in the way and generates feelings of jealousy, anger, greed, sadness, and so on. One need not cultivate upeksha in the face of injustice. Rather, when faced with injustice, the mind’s natural state is upeksha - it is the layer of conceptual thought that gets in the way and generates feelings of anger, righteous indignation, apathy, and so on.

Rumi puts this teaching beautifully:

“Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.”

- Rumi

This is true for each of the four attitudes. Maitri, or friendliness, is the natural state when confronted with the happiness of another. Karuna, or compassion, is the natural state when confronted with the suffering of another. Mudita, or gladness, is the natural state when confronted with something good happening to (or done by) another, and Upeksha, or equanimity is the natural state when confronted with something bad happening to, or done by, another.

Let’s put a pin in this for a few moments, and recap another relevant topic - vivek, or discernment.

Through the various practices of Yoga, especially the eight limbs, we start to develop viveka - the power of discernment. This viveka helps us to notice things that we previously, with a scattered mind, could not notice.

For example, one may notice simple things, like the direction the flowers point in the mornings, or the different bird calls depending on the temperature or the wind. We may also start to notice more complex patterns, such as the way the mind functions when certain Yamas are practised versus when they are not, or the speed at which your manas is able to move between senses depending on what you ate for dinner the night before.

Along with these, comes an additional, visceral observation - the fact of dukkha.

दुःखं एव सर्वं विवेकिनः॥Dukkham eva sarvam vivekinahEverything is, indeed, suffering to the one with Vivek (ie. discernment).

- Yoga Sutra, 2.15

We have previously discussed, at length, how all of life is essentially a movement away from dukkha (unease) and towards sukha (ease). Every single thing we do - from things as big as having children to things as small as shifting in your chair as you read this - are only for this purpose - to avoid dukkha and to pursue sukha.

That is, we are all just trying to make our ride a little smoother.

What’s more, we are all faced with the facts of sickness, disease, and death. Normally, the scattered mind is able to distract itself from these fundamental truths with sense pleasures, various problems of conceptual creation, and activities. The mind is quite good at this, and takes every problem seriously, justifying its seriousness with convention.

However, when vivek becomes strong, and the mind becomes more focused, we are unable to avoid these truths, and are forced to confront them head-on.

Previously, we may have heard the teaching that all living beings suffer, and may even have had some degree of compassion. Very quickly, though, the mind would resort to its usual patterns of likes, dislikes, and distractions, thus avoiding fully touching the suffering directly.

When the mind is able to retain focus, however, it is forced to stare the fact of suffering in the eye, since it has become too sharp to ignore when attention is wavering due to distraction. Here, the Yogi can no longer hide their head in the sand without knowing that they are, in fact, hiding their head in the sand.

Normally, with a scattered mind, we perceive our own happiness and suffering, as well as the happiness and suffering of others, as relative. That is, we perceive others as happy or unhappy relative to ourselves. To be more specific, we perceive (loka-pratyaksha) others as happy or unhappy relative to the saamaanya, or the conceptual image, or ourselves (shabda and jnana).

The reason for this is that we have been conditioned over a long time to have a special attachment to this shabda and jnana - this saamaanya - called “me”, and we see the entire Universe as relative to this saamaanya.

In Nirvichaar Samaadhi, however, shabda and jnana have dropped away, and with it goes the conceptual construction of “me.” Then, the entire Universe is no longer perceived as relative to “me”, but just as it is - without a center.

This results in the absence of the feeling of “I”, which automatically dissolves any feeling of incompleteness or dukkha as long as the state of Samaadhi persists.

What’s more, when this happens, where we normally saw the suffering of others as relative to our own suffering, we now see the suffering of others just as it is - with Para-Pratyaksha - and are able to touch it - the vishesha - directly, without any intervening layer of conceptual thought.

When we are able to touch this suffering directly, without any intervening layer of conceptual thought, an intense feeling of compassion naturally and effortlessly wells up in the mind.

Then, when this is repeated, the mental channel towards this kind of intense compassion becomes the normal tendency, and the Yogi starts to feel compassion towards all beings everywhere, no matter what they may seem like on the surface. The words and ideas which obscured the compassion are now gone, and the light of compassion shines through at all times.

Until next time:

Review the articles on the Brahmavihaaras, try practicing them in your day to day life, and notice the effect on your state of mind:

When you see someone suffering, notice what is blocking the compassion in your mind from shining through. Take notes to find patterns, and systematically work to break them down during meditation.

Ask any questions here:

Next time: You can only believe in what you don’t know

While this quote talks about Moksha, or “enlightenment”, this particular effect happens prior to Moksha, once Nirvichaar Samaadhi has been stabilized.