Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Often, when we think of Yoga, we imagine difficult poses, stretchy pants, and perhaps even stretchier people. For some of us who are a little more familiar, we may also think of breathing techniques or meditation.

While all of these - physical postures, breathing techniques, and meditation - are a part of Yoga, they are only three of the eight limbs.

As discussed in last week’s article, the purpose of Yoga is far beyond a calm mind and a healthy body. The ultimate goal of Yoga is nothing short of complete freedom from all suffering, called Moksha.

Moksha is not some “holy” or “blissful” state or some sort of psychedelic, mystical experience to be put on a pedestal and attained at some future point in time - it is our current state right now, we just don’t see it clearly.

This lack of clarity about our true nature is called avidya, and as we have discussed, it is the root cause of all suffering. To be clear, this is not to say that avidya is “bad” in any way, it is just a matter of noticing the facts.

This avidya, or primal ignorance, manifests in the four confusions that we have been discussing over the last couple of weeks.

To recap, they are:

Confusing the impermanent to be permanent

Confusing the unclean to be clean

Confusing suffering to be pleasure

Confusing the non-self to be Self

Unlike regular old ignorance, which is a negative entity, this ignorance is a positive entity (bhaavaroopam) that needs to be removed in order to uncover the Self. This is similar to how a sculptor removes stone to reveal the sculpture, or as clouds must clear out to reveal the clear sky. A good example to make this clear is the difference between the common-sense concepts of a truth, silence, and a lie.

A truth is a positive entity - words that reflect evidence. Silence is a negative entity, and can be filled with either a truth or a lie. A lie, however, is also a positive entity - there are words being said, but they do not reflect the evidence. In order to get rid of a lie, there are two steps - it must first be seen as a lie, and then corrected with the truth. Similarly, avidya can be seen as a series of lies that we tell ourselves. These lies are the four confusions, and they are what keep us feeling like we are a body with a mind, and perhaps some sort of entity floating behind the eyes.

P: How do we actually get rid of avidya? I understand the four confusions theoretically, but they seem so deep-rooted and difficult to get rid of in practice.

These confusions are indeed deep-rooted, and rooting them out takes discipline, internal honesty, vigour, and a constant meta-awareness of the mind.

P: Ok, but as the sculptor uses a chisel to remove stone, what is the chisel that I can use to remove avidya?

Jogi: The sculptor uses two things - a chisel, and their ability to sculpt. A chisel in the hands of a farmer or a painter is useless. The hands must also hold the skill of sculpting. In this way, the ability to sculpt is vivek, and the chisel is called samyam.

विवेकख्यातिरविप्लवा हानोपायः॥VivekaKhyatirAviplavaa hanaUpaayaThe trick1 [to get rid of avidya] is non-fluctating Vivek (ie. discriminative power).

- Yoga Sutras, 2.26

In Raja Yoga (the path of meditation, which we are currently discussing), the tool used to remove avidya is called vivek (pronounced viv-ache), or discrimination. Specifically, this is the ability to clearly discern one thing from another, and is likened to the ability of an ant to carefully separate sugar from sand.

As you can see with the four confusions, avidya is a matter of lack of continuous vivek. We are unable to clearly discern between the impermanent and the permanent, between the unclean and the clean, between the painful and the pleasurable, and between the non-self and the Self, and this lack of clear discernment is the cause of our dukkha. What’s more, while we may be able to understand the theory, catch “glimpses” every now and then, or see the Truth more clearly in times of great loss, the moment a stressful situation comes up, or the moment we get caught up in the drama of our lives, we fall right back into the confusion, and the cycle of suffering starts all over again.

But vivek by itself is not enough, it must also be continuous.

P: But how do we strengthen our vivek and ensure that it is continuous?

योगाङ्गानुष्ठानादशुद्धिक्षये ज्ञानदीप्तिराविवेकख्यातेः॥YogaAngaAnushtaanaadAshuddhiKshaye GyaanaDeeptirAaVivekaKhyaatehThrough the sustained practice of the eight-limbed Yoga, the impurities are removed, and the light of wisdom culminates in the clarity of Vivek.

- Yoga Sutras, 2.28

The method to cultivate vivek is called the Eight-Limbed Yoga, or Ashtaanga Yoga (pronounced uh-sh-taahng-uh), and will be the subject of the next several articles in this series.

This skill of vivek is the key to Yoga - but what is it exactly?

क्षेत्रक्षेत्रज्ञयोरेवमन्तरं ज्ञानचक्षुषा | भूतप्रकृतिमोक्षं च ये विदुर्यान्ति ते परम् ||KshetraKshetragyayorEvamAntaram jnaanaChakshushaaBhootaaPrakritiMoskham cha ye vidurYaanti te paramThose who can clearly distinguish between the field (ie. the body-mind) and the Knower of the field (ie. Pure Consciousness), and can see the path to liberation from material nature, reaches the Supreme Destination (ie. freedom from suffering).

- Bhagavad Gita 13.35

Simply said, vivek is the power to distinguish one thing from another. This is not some mystical or magical skill - you already have it right now. Consider your current experience reading these words. In order to read the words, you are separating the words from the background. This ability to separate two things from each other is vivek, and the function of mind that you are using to do this is called the buddhi (ie. the intellect). Also notice, in order to use vivek, your mind has to be somewhat calm. That is, if you were agitated or distracted, reading would be a difficult task, even though you know how to do it.

Now separating the text from the background may seem simple to you, but the reason it seems easy is that you have been practicing this skill for a long time.

Let us consider the example of music. A musician with years of ear training is able to distinguish the separate notes in a chord. They use their power of vivek to do this, and given the amount of practice they have put into this skill, it may seem easy for them. However, for someone who does not have that kind of ear-training, distinguishing the individual notes in a chord is a difficult task.

Another example, consider a sommelier. With their years of training and experience in tasting different wines, they are able to easily distinguish between different types of wine, and perhaps even within a given wine, they can distinguish the different flavours (e.g. “an oaky flavour with a hint of raspberry and notes of chocolate”). On the other hand, for the average person, it is extremely difficult to tell the difference between wines, let alone the individual flavours!

This example can be extended to any skill. Visual artists and designers can easily distinguish between different colours, software developers can easily distinguish between good and bad code, doctors can distinguish symptoms from one another, and the speakers of a language can distinguish between different words, while for a non-speaker, the words seem to merge together.

What we ordinarily call “learning a skill” is, in terms of Yoga psychology, a strengthening of the buddhi to apply vivek on a particular object.

When it comes to Yoga, the object is avidya, and once the mind is calmed, the buddhi must then be strengthened enough to apply vivek to the four confusions.

But this is easier said than done.

As with any skill, perfection of Yoga takes a continuous application of vivek. However, while with other skills you only have to apply vivek in particular situations (e.g. when you are reading, tasting wine, looking at colours, listening to music, etc.), the Yogi needs to apply vivek at all times, in all places, and for all objects.

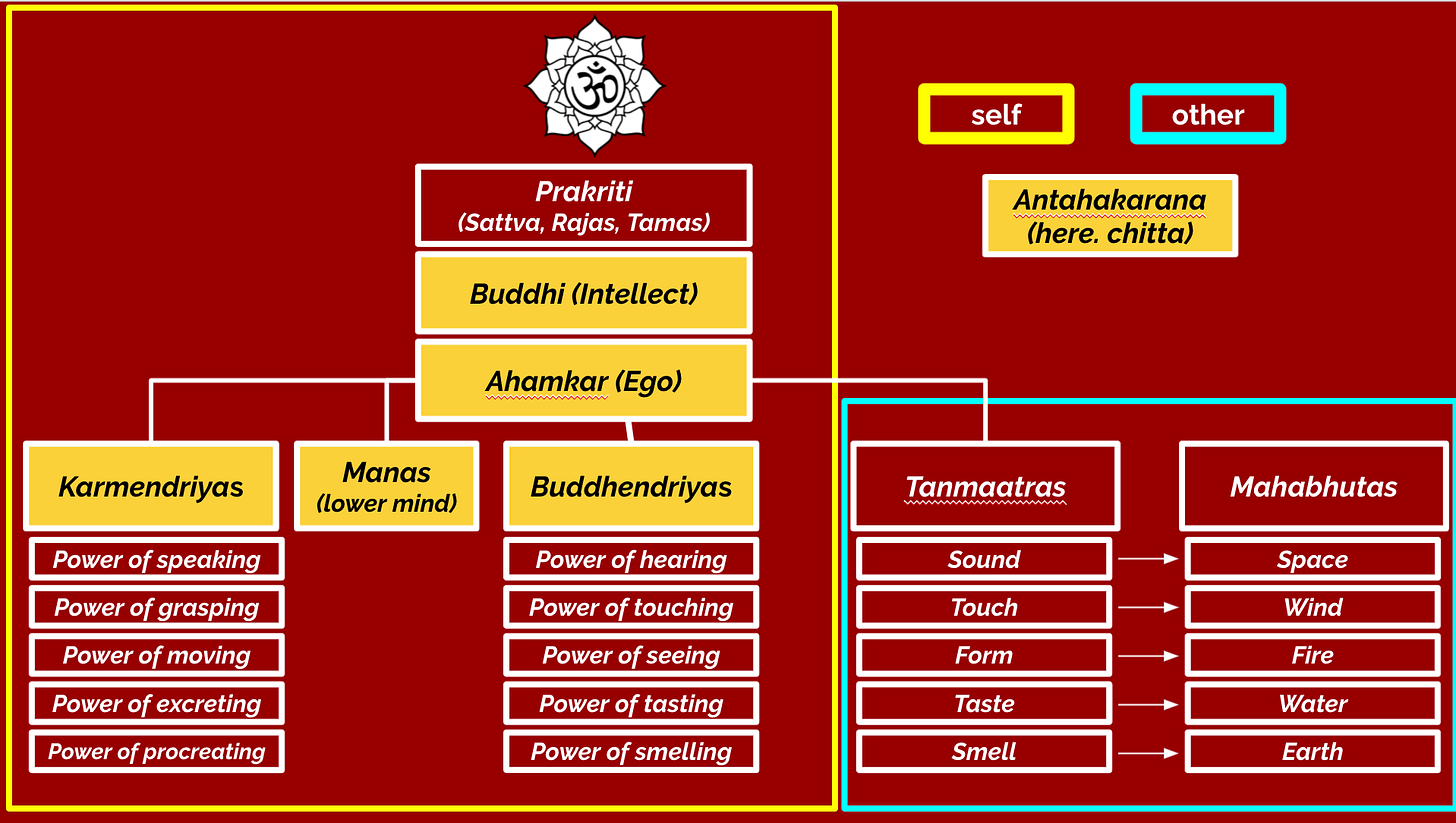

What’s more, while with other skills, the focus is on gross objects (music, colours, wine, etc.), in Yoga, the objects get more and more subtle as meditation deepens (e.g. tanmaatras, buddhendriyas, manas, etc.). We will discuss this more in a future article when we discuss breadth vs. depth of meditation.

The reason this poses a challenge is that the more subtle the object gets (ie. the higher it is in the diagram of the 25 Tattvas, above), the more difficult it is to focus on. To make this clear, it is a lot easier to continuously focus on the words in front of you than it is to continuously focus on your sense of sight. It is a lot easier to continuously focus on your sense of sight than it is to continuously focus on your mind, and so on up until the buddhi. Don’t take my word for it, you can try this for yourself.

This means that removing avidya takes a continuously calm mind, significant concentration, and razor-sharp, steady attention.

Normally, our minds are all over the place. Our attention flits from on object to another - phone, laptop, thoughts, social media, music, food, likes, dislikes, fears, whatever. But this isn’t enough - we actively cultivate this constant fluttering of attention by allowing distraction, by satisfying desires, and by chasing mental and physical objects like a cat chasing a laser pointer. Now this isn’t a good or bad thing, it just makes it more difficult for us to focus, and so more difficult for us to break away from avidya, thus keeping us bound in the cycle of suffering. This is where the preliminary practices of Yoga are helpful. Through eka-tattva-abhyaas, cultivation of the four attitudes, and the stabilising techniques, the mind becomes calm enough to start turning inwards rather than chasing objects. Then, Kriya Yoga increases the will-power, that is the ability of the buddhi to control the mind and body enough to actually practice rather than just philosophise.

It is here that the eight limbed Yoga begins.

Ashtaanga Yoga: The Eight Limbed Yoga

यमनियमासनप्राणायामप्रत्याहारधारणाध्यानसमाधयोऽष्टावङ्गानि ॥YamaNiyamaAsanaPraanayaamaPratyaahaaraDhaaranaaDhyaanaSamaadhayo’AshtaavAngaaniThe eight limbs are Yama, Niyama, Aasana, Praanaayaama, Pratyaahaara, Dhaarana, Dhyaan, and Samaadhi.

- Yoga Sutras, 2.29

To summarise, the eight limbs of Yoga are as follows:

Yama: External observances

Niyama: Personal conduct

Aasana: Posture (this is the usual Yoga in most Yoga studios)

Praanaayaam: Lengthening of the “Praana” (including breathing)

Pratyahaar: Sense withdrawal/disengagement

Dharanaa: Concentration/Flow (this is how “meditation” is usually taught)

Dhyaan: Meditation

Samaadhi: Meditative Absorption

We will spend more time on each limb in the articles following this one, but here is a brief summary of each limb so that we can get an idea of the process.

1. Yama: External observances

The Yamas (pronounced yuh-muh) are the first limb of Yoga, and they involve the Yogi’s interactions with the external world, simplifying them so that they are no longer a distraction to the mind. They are a set of methods to use our daily actions and interactions to weaken the boundary between “self” and “other”. There are five Yamas - non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, non-indulgence, and non-ownership.

2. Niyama: Personal conduct

The Niyamas (pronounced nee-yuh-muh) are the second limb, and are one level more internal than the Yamas. They deal with the Yogi’s personal conduct, improving will-power, increasing knowledge, and creating a fertile ground for the following limbs. There are five Niyamas - cleanliness, contentment, Self-study, Self-discipline, and Self-surrender. Notice, the last three Niyamas are identical with Kriya Yoga. This is an excellent example of how Yoga systematically builds on itself.

3. Aasana: Posture

This is what most people know as “Yoga.” Aasana (pronounced aah-suh-nuh) literally means “seat”, and is perfected when the Yogi can sit in a stable and comfortable position for an extended period of time. The goal of Aasana is that the body is not a distraction, so that the Yogi can move further inward. There are a number of physical postures that target particular muscle groups so that the individual practitioner can use them to ease tightness or gain strength in certain areas in their body, with the goal of a stable and comfortable seat. However, these postures are just a preliminary step along the way, not the goal of Yoga.

4. Praanaayaam: Breathwork

Praanaayaam (pronounced praah-naah-yaahm) literally means “lengthening of the Praana.” Praana is not exactly breath, although breath is one its more visible effects. It is the life force, often translated as the “vital air”, and can be likened to chi or qi from traditional Chinese medicine. The practice of Praanaayaam in Yoga includes, on an external level, particular breathing exercises and patterns that regulate the flow of Praana in the body, and a multitude of much more subtle practices, with the goal of ensuring that the inner functioning of the body is not a distraction to the Yogi, enabling them to move further inward. The practice of Praanaayaam also helps to create a fertile ground for deeper meditation, and weaken the effect of karma (more on karma in a future article).

5. Pratyaahaar: Sense withdrawal

Pratyaahaar (pronounced pruh-tyaah-haahr) is a set of practices that enable the Yogi to withdraw, or rather, disengage from their senses. This is not just the five conventional sense organs (buddhendriyas), but also the karmendriyas (the five organs of action). This enables the Yogi to go deeper into meditation regardless of the sense stimulus around them. With pratyaahaar in place, the Yogi can go into the deepest meditation even on the busiest of streets.

6. Dhaaranaa: Concentration

Dhaaranaa (pronounced dhaa-ruh-naa) means “flow” or “stream”, and is essentially the practice of concentration. This is most commonly what is taught as meditation, but is actually a (necessary) step prior to it. Bring the mind to an object (e.g. the breath), and when it wanders, bring it back to the object. Over time, this trains the wandering manas to be controlled by the buddhi, enabling the mind to focus on whatever the Yogi desires. Additionally it trains the Yogi to be seated in the buddhi. In practice, this means that the Yogi gains a sort of meta-awareness of what they are thinking, saying, and doing, at all times, rather than simply running on past habit patterns.

7. Dhyaan: Meditation

Dhyaan is most often translated as meditation. Incidentally, it is the Sanskrit word from which the Pali word “Jhana” and the Japanese (Romanization) “Zen” is derived. Dhyaan is defined by Patanjali as when the mind is able to focus on single object for successive moments without interruption. This is the tool that is used to weaken kleshas from the weak/attenuated state into the dormant state. Once the Yogi is able to achieve dhyaan, this fine-tuned attention is turned on kleshas. However, this is not the final stage.

8. Samaadhi: Meditative absorption

Samaadhi (pronounced sum-aah-dhee) is complete meditative absorption. In Samaadhi, the trinity of observer, observed, and observation seem to merge together, and the object shines alone, with no intervening words or ideas. There are several stages of Samaadhi, but they fall into two main categories - sabeeja or samprajnaat (with support), and nirbeeja or asamprajnaat (without support). The second category - samaadhi without support - is the final stage of the eight limbed Yoga.

Samyam: The chisel

The set of Dhaarana, Dhyaan, and Samaadhi, practiced together, is known as Samyam (pronounced sung-yum, with a silent “g”). Once samyam is sharpened, it is then applied at successively more subtle tattvas, until eventually it is applied to the buddhi. Once this is perfected, the nature of the Purusha (the Self) becomes clear, and this is known as Kaivalyam, or Enlightenment (aka Moksha, in the Yoga tradition).

These eight are not necessarily steps, although they can be practiced in that way. Rather, they are like limbs (hence the name, ashta-anga, or eight-limbs). There is a certainly a sequence, in that if you start with the first limb and move on to later limbs, you will find the later limbs easier (e.g. if your Aasana, or posture is steady, you will find it easier to do Dhyaan, or meditation). However, the later limbs also help to solidify earlier ones (e.g. if you have a regular meditation practice, you will find that your Yamas and Niyamas become more stable, ie. you become more non-violent, more honest, etc.).

Additionally, you may notice that the eight limbs work from the outside inward. As the Yogi works on each limb, that level of their existence becomes less of a distraction, making it easier to progress in the successive limbs. Using the foundational principle of vairaagya, the Yogi “lets go” in order to go further inward.

These eight limbs are the method to increase vivek, and sharpen the chisel of samyam of so that the Yogi becomes skilled enough, and the chisel becomes sharp enough that it can be applied to the four confusions of avidya. Practically, this looks like two sides to the practice - one side is to sharpen the chisel, and the other side is to apply it. This is similar to a warrior, who spends time sharpening their sword and practicing their art, and then uses that sword to go into battle. However, the analogies of the warrior and the sculptor break down at this point - while sharpening a chisel or a sword is worthless if the tools are not used later on, with Yoga, just the work of sharpening samyam and increasing vivek has some very real benefits. The mind becomes calmer, clearer, and more joyful, concentration increases, and the body becomes healthier too.

नेहाभिक्रमनाशोऽस्ति प्रत्यवायो न विद्यते |स्वल्पमप्यस्य धर्मस्य त्रायते महतो भयात् ||NaIhaAbhikramaNashoAsti pratyavaayah na vidyateSvalpamApiAsya dharmasya traayate mahato bhayaatIn this (Yoga) there is no loss of effort, nor any adverse result. Even a little bit of effort saves [the Yogi] from great fear.

- Bhagavad Gita, 2.40

Having said this, the eight-limbed practice is not for the faint of heart - it is not like a pill that you can pop and be done with. Rather, it is a lifestyle to be carefully cultivated over an entire lifetime. The four keys to practice are important to remember here - it takes a long time, with incessant practice, ruthless internal honesty, and paying close attention. It is is not a palliative - like something you take when you have a headache. The purpose of Yoga is not just a calm mind or a healthy body. While those are side-effects, the purpose of Yoga is the cessation of all suffering.

Finally, this eight-limbed practice requires, as a preliminary, a somewhat stable mind (specifically, vikshipta bhumi). If this is not your current bhumi, you may find it easier to begin with the preliminary practices.

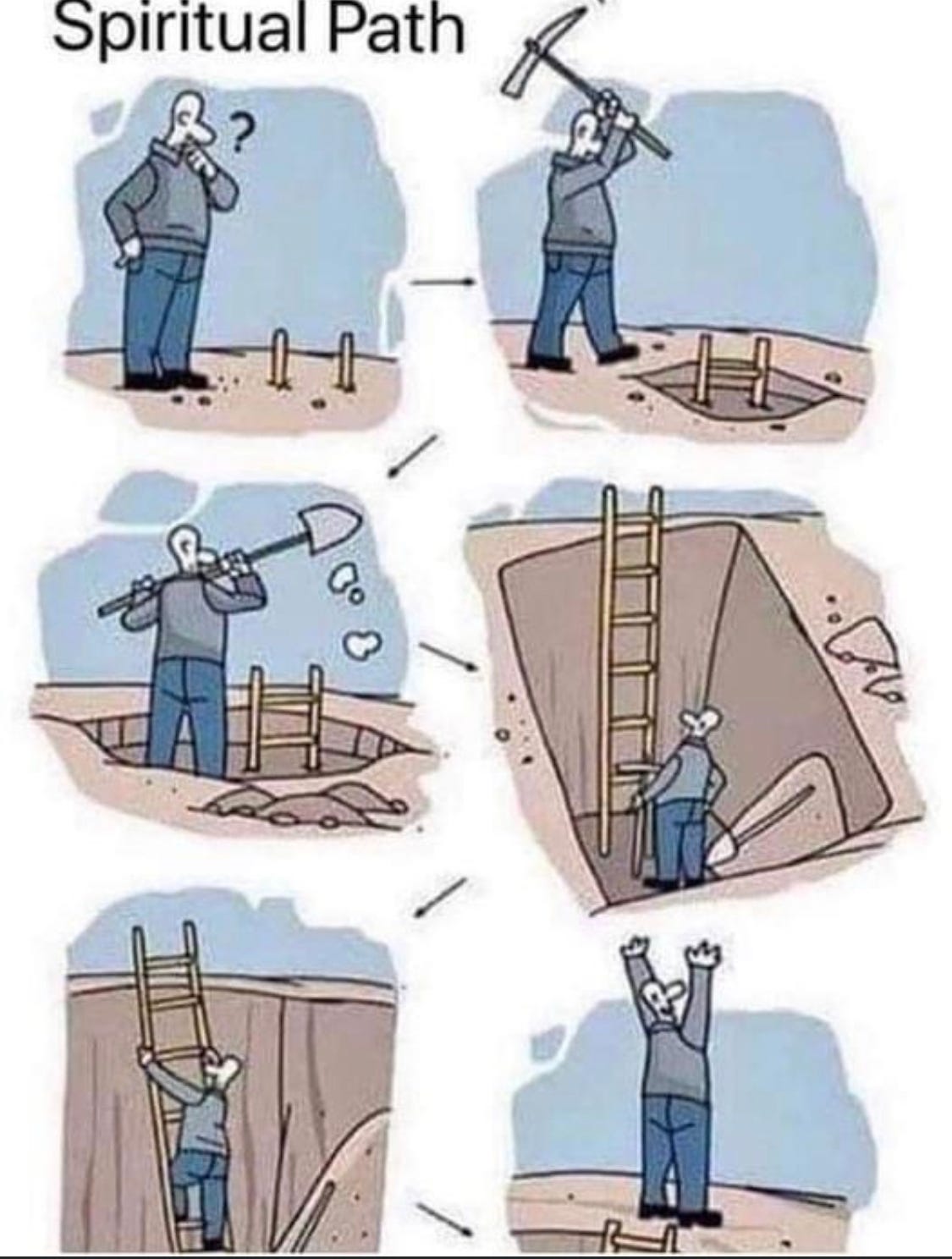

To summarise this, the order of operations is as below, continuing to practice the previous steps as you go along to the next ones.

Until next week, continue your practice of these steps to prepare the mind for the following stage. If you are already a regular meditator, or want to start a meditation practice, you will find that practicing these will make it easier for you to sit down and meditate and access deeper states:

Over the next several weeks, we will dive into each of the limbs in more detail. The goal is to provide you with the tools to be your own teacher, so that you can apply the tools of Yoga to our own body and mind on your journey to freedom.

Next time: The Yamas: The First Limb of Yoga - Ahimsa (non-violence)

The use of the word upaaya is important to note. Upaaya means trick. Yoga is, from the Ultimate perspective, like a trick played on the Yogi to make them realise that there is in fact, no path to the Ultimate Truth. We will discuss this more later, but one can consider it similar to the question “what is the path to here?” All ways will work, and at the same time there is no way. No matter where you go, you are always “here.” The question itself is meaningless. You are already here. To quote Jiddu Krishnamurti, “Truth is a pathless land.”

Thank you for this Kunal! 🙏 while ashtanga yoga and Bhakti yoga both appear to be two completely separate paths that lead to the same goal, I can’t help but think that there must be aspects of both that need to be present in order to attain moksha. While ashtanga yoga is a very methodical and logical path towards achieving liberation, isn’t there some element of gods grace that also needs to be present? Or is it that because both paths require surrender, following either one naturally opens you up to gods grace? Also, it seems like following any one path naturally brings aspects of the other one into your awareness as well.