Four methods to withdraw the senses

Pratyaahaar in practice

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Over the past two weeks, we have been discussing the fifth limb of Yoga - Pratyaahaar, or sense withdrawal.

Pratyaahaar is a bridge between the external and internal limbs of Yoga, and can be seen as a pathway to meditation. By abstracting the senses from involvement with their respective objects, the mind is free to move further inward toward the Self.

P: What’s the difference between the Pratyaahaar and Yamas?

Jogi: What do you mean?

P: Take the example of brahmacharya. If I decide to follow brahmacharya, that means that I don’t indulge my sense desires mindlessly, is that correct?

Jogi: Yes.

P: Isn’t that the same thing as Pratyaahaar?

P’s question here is not only relevant to the Yamas, but extends to the other limbs as well. For example, consider santosh, or contentment. The practice of santosh requires the letting go of trishnaa, or “the great thirst” for sense objects, and cultivating contentment for what one has. This sounds a lot like Pratyaahaar.

Another example is tapas, where the Yogi trains the body to act in accordance with their will (the buddhi, or nishchaya-vritti).

A third example is Aasana. In Aasana, the body is made to become completely still, and all effort is released. This is a stilling of the karmendriyas (organs of action). This also sounds a lot like Pratyaahaar.

The difference lies in the level of depth.

Consider the following example.

In order to move a car, you can:

Put it in neutral, and push the car forward.

Put it in gear, and press the accelerator.

The earlier limbs of Yoga are more like the first option, where the action is done at the surface level. Pratyaahaar is like the second option, where the action is more internal, and therefore more effective.

Both options move the car forward, and similarly, both the earlier limbs and Pratyaahaar achieve the same outcome - weakening of outgoing tendencies. However, Pratyaahaar is more subtle, and so requires more practice.

The earlier, external, limbs of Yoga act on the outer layers of the Yogi’s being. For example, with aparigraha, the Yogi gently and systematically stops themselves from thinking, saying, or doing anything that generates a feeling of “ownership”. This is only one manifestation of sense activity, and happens on a more gross layer of our being.

Another example is shauch (cleanliness). Taking the example of alcohol or unhealthy food for this Niyama, one may have a strong desire to drink alcohol or eat unhealthy food. The practice of shauch in this scenario would be to gently and systematically stop oneself from consuming anything that would agitate the mind or body. However, this is only one manifestation of sense activity, and happens at the level of personal conduct.

Underlying both shauch and aparigraha (and all the other earlier limbs for that matter), is Pratyaahaar, where the indriyas (the powers of both sense and activity) themselves are brought under the control of the buddhi (the intellect).

In the beginning, while our kleshas (mental colourings) are strong, practicing the Yamas and Niyamas can be a huge challenge. However, with perfection in Pratyaahaar, all the Yamas and Niyamas become effortless.

Another, more traditional example to make this clear is rooting out weeds in a garden. One option is to cut stems one by one. This works, but is not as effective as pulling out the root. There is just one root, but many stems.

In the same way, Pratyaahaar is at the root of all the limbs that precede it.

How do I practice Pratyaahaar?

There are several techniques to practice Pratyaahaar. You may find some to be more effective for you than others. Every practitioner is different, and so, as with all of Yoga, it is important to experiment to find what works best for you.

Mindful watching

This technique is often taught as a precursor to meditation, and, in some traditions, is taught as meditation itself. It is one of simplest and most powerful techniques to calm the mind and prepare attention to turn back in upon itself.

However, in Yoga, it is only a precursor to meditation, albeit extremely powerful.

Sit in your Aasana, close your eyes, and do a few rounds of your favourite Praanaayaam.

Return to normal breathing, and bring your attention to the breath.

Notice the sensations of your breath. You may feel it more under your nostrils, at your belly, or elsewhere in your body. Notice if it is hot or cold, smooth or jerky, and start to feel how every inhale is slightly different from the last.

Keeping your breath as an anchor, broaden your awareness to other sensations. Watch them rise and fall without judgement. Simply notice them, and watch them with curiosity.

With some practice, you will start to notice your kleshas. A good way to find these are to notice which sensations draw your attention more easily than others. Once you find these tendencies, notice the feeling of attraction and aversion, without judgement. Watch until you notice how the sensations are not “good” or “bad”, but rather that they arise, and alongside them arises a sensation of attraction or aversion. Notice how attraction and aversion are also objects in your awareness.

After some time, you may start to feel restless, wondering when the timer will run out and you can get up again.

Notice the feeling of restlessness in your body, with the same curiosity. Where do you feel it? In your chest? Your ears? Your forehead? How does it affect your breath? Stay with the sensation until it fades away, and notice where it fades into.

After some time of this, the mind may get bored of noticing gross objects, and will turn to thought. You may start thinking about your day - things that happened or will happen. In Yoga, these thoughts are a type of “subtle” object. They are also heard, seen, etc., except that the sensing happens in the mind. Just as you noticed the external objects and let them go, repeat the same exercise with the subtle objects.

Eventually, the thoughts will cease, and it will feel like a deep silence. It is at this point that the mind is prepared for the next limb - Dhaaranaa, or concentration.

Using a Yantra

The purpose of Pratyaahaar is to strengthen the buddhi’s control over the indriyas. Remember, the indriyas are not the external organs (e.g. the eyes, the ears, the mouth, etc.), but rather the internal powers (e.g. the power of seeing, hearing, grasping, talking, etc.).

Among other benefits, this exercise helps with:

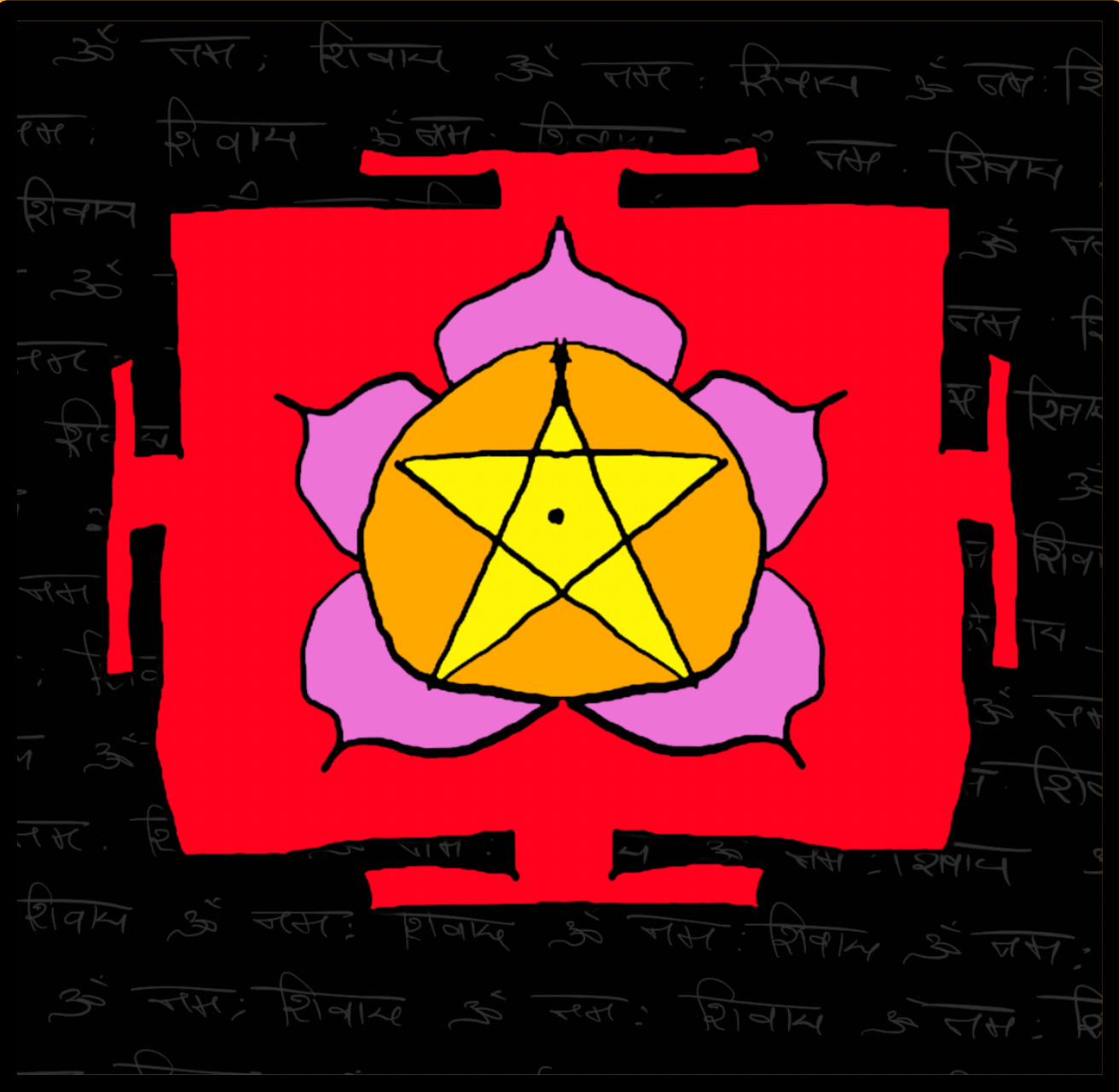

This technique uses a Yantra (यन्त्र, literally “machine”, “tool”, or “supporting instrument”) to calm and restrain the wandering manas.

The Yantra in the diagram below is known as the Panchaakshari ShivaYantra (the “Five-lettered” Shiva Yantra), since it has a five-pointed star, with each point representing one of the five syllables in the Panchaakshari Shiva Mantra - Om Namah Shivaaya (ॐ नमः शिवाय; the five syllables are na, mah, shi, vaa, and ya).

The five points of the star also represent the five gross elements, the five subtle elements, the five praanas, the five koshas1, the five karmendriyas (organs of action), and the five buddhendriyas (sense organs).

The technique is as follows:

Sit in your Aasana, close your eyes, and do a few rounds of your favourite Praanaayaam.

Return to normal breathing, and bring your attention to the breath.

Once the mind has settled, open your eyes, and bring your complete attention on the dot in the center of the Yantra. This dot is called the bindu (बिंदु).

With the eyes trained on the bindu, move your attention to the top left point of the star. Hold this for one breath.

Bring your attention back to the bindu. Hold here for one breath.

Without moving your eyes from the bindu, move your attention to the top point of the star. Hold this for one breath.

Bring your attention back to the bindu. Hold here for one breath.

Again, without moving your eyes from the bindu, move your attention to the top right point of the star. Hold here for one breath.

Bring your attention back to the bindu. Hold here for one breath.

Continue in this way, making your way around the star, without moving your eyes away from the bindu.

Notice how your indriya of sight is able to separate from the movement of the physical eyes. This distinction between the eyes and the indriya of sight allows you to see clearly the level at which Pratyaahaar happens. It is not about your eyes looking or not looking, rather it is the indriya that has to be mastered.

While this technique uses the sense of sight, the same technique can be applied to any of the other senses.

In the beginning, you may find that your attention wavers, and it is difficult to hold the attention at a different place from where the eyes are focused. With time, it will become easier.

Once it becomes easier, keeping the eyes trained on the bindu as before, try to move the attention between the points of the star faster. Once this becomes easy, try to modulate the speed - sometimes faster sometimes slower.

Finally, you can start to expand the reach of your attention. At first, you start with the eyes on the bindu and the attention on the points of the star. Now, keeping the eyes on the bindu, try the same exercise with the points of the lotus petals, then expanding to the corners, or walls, of the Yantra, and eventually to the room surrounding you, until you reach the very edges of your awareness.

If the mind wanders, you can even use the Yantra to “catch” your attention.

If the mind is moving fast, start by moving your attention around the Yantra faster, and then gradually slow it down. Moving the attention around feels the easiest when the speed of movement is about the same “speed” as the mind.

This technique can be likened to building muscle at the gym by lifting weights. At first, you can only lift a certain amount of weight. Then you are able to increase the weight more and more. However, the increased strength of your muscles can be used outside of the gym too. Perhaps you weren’t able to lift heavy boxes, but now, after going to the gym you can easily do so - using the same muscles that you strengthened by lifting weights.

Similarly, with this technique, you can get better and better at moving your attention at will. Then, you can use the same “muscle” to “catch” your attention when it gets distracted, especially during meditation.

Cycling through the indriyas

Pratyaahaar can be seen as a practice of vairaagya, or “letting go” of your indriyas. You have the powers of hearing, touch, sight, grasping, moving, and so on, but during practice you choose (with the buddhi) not to use them.

The mind has a natural tendency to go outward in the direction of objects. With ten indriyas, this can be quite a task, especially if the mind is not yet trained.

Given this difficulty, the following method is a systematic way of letting go of the indriyas, one by one, until attention has nowhere to go but inward.

This technique uses the seven chakras (literally “wheel”, pronounced chuh-kruh, not shaah-kraah), and association with these points as a way to hold the attention. If you choose to use the beej mantras associated with each chakra, the “m” at the end is pronounced as in the “n” in the word “sing.” We will not get into the meaning of the chakras just yet, but for now just use them as a way of associating the indriyas with different places in the body2:

Sit in your Aasana, close your eyes, and do a few rounds of your favourite Praanaayaam.

Return to normal breathing, and bring your attention to the breath.

Once the mind has settled, bring your attention to your mooladhaara chakra, at the pelvic floor, reciting the mantra “lam” (लं, pronounced “lum”). Consider your power of excretion, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Move your attention up to your svaadishthaana chakra, in the abdomen, reciting the mantra “veem” (वीं, pronounced “veem”). Consider your power of reproduction, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Bring your attention to your manipoora chakra, behind the navel, reciting the mantra “room” (रूं, pronounced “room”). Consider your power of movement, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Lift your attention to the anaahata chakra, near the heart, in the center of the chest, reciting the mantra “yaim” (यैं, pronounced “yaim”). Consider your power of grasping, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Shift your attention to the vishuddha chakra, in the middle of the throat, reciting the mantra “haum” (हौं, pronounced “haum”). Consider your power of speech, including internal speech, and your control over it. You are able to use it but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Raise your attention to the ajna chakra, at the point behind the center of your eyebrows, reciting the mantra “Om” (ॐ, pronounced as in “home” without the “h”). Consider your power of attention as the reigns through which the indriyas are being withdrawn, as a turtle withdraws its limbs into its shell. Release any desire for action, letting it all go until the bell rings.

Now bring your attention back to the mooladhaara chakra, at the pelvic floor, reciting the mantra “lam” (लं, pronounced “lum”). Consider your power of smell, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Move your attention up again to your svaadishthaana chakra, in the abdomen, reciting the mantra “veem” (वीं, pronounced “veem”). Consider your power of taste, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Bring your attention to your manipoora chakra, behind the navel, reciting the mantra “room” (रूं, pronounced “room”). Consider your power of sight, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Lift your attention to the anaahata chakra, near the heart, in the center of the chest, reciting the mantra “yaim” (यैं, pronounced “yaim”). Consider your power of touch, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Shift your attention to the vishuddha chakra, in the middle of the throat, reciting the mantra “haum” (हौं, pronounced “haum”). Consider your power of hearing, including listening to your own internal vocalizations, and your control over it. You are able to use it, but are choosing to let go of it until the bell rings. Hold your attention here at this spot, and slowly release any intention to use this power for the time being.

Raise your attention to the ajna chakra, at the point behind the center of your eyebrows, reciting the mantra “Om” (ॐ, pronounced as in “home” without the “h”). Once again consider your power of attention as the reigns through which the indriyas are being withdrawn, as a turtle withdraws its limbs into its shell. Release any desire for action, letting it all go until the bell rings.

Finally, raise your attention to the sahasraara chakra at the crown of your head. Imagine a thousand-petalled lotus, and try to move your sense of “I” upward into this point.

Repeat this until the timer runs out.

This practice takes time to master, but is extremely powerful if practiced diligently with the four keys to practice. It looks like a lot of steps, but it is really quite simple, and can be extended to hold the attention with the colours and shapes corresponding to the individual chakras.

Eventually, you may find that in the final step of this process, you feel a deep sense of silence. When this happens, Pratyaahaar is complete, and the mind is ready for the next limb.

“Boring” the mind

Sometimes, during meditation, we may get distracted with sense objects. The power of hearing is generally the most common offender, but it can happen for other indriyas as well. Try to remember a time that you were meditating, or otherwise trying to focus, and suddenly a loud or annoying sound pulled your attention outward. What happened?

Usually, the mind goes into a state of conflict, trying to push the sound out, or to pull the attention back by force. This force usually makes it worse, and the feeling of annoyance increases until any sense of peace or clarity is gone. Using force to hold on to attention is like trying to hold on to water by grasping more tightly.

Rather, this method is a way to induce Pratyaahaar using the principle of vairaagya, or letting go:

Sit in your Aasana, close your eyes, and do a few rounds of your favourite Praanaayaam.

Return to normal breathing, and bring your attention to the breath.

Once the mind has settled, notice the most “distracting” sensation. If you don’t have a distracting sensation, you can click on this link for the sounds of traffic.

Notice the sensation of sound in your left ear. Keep your entire attention here, completely leaning into it.

Once the mind starts to turn inward into thoughts, gently bring your attention back to the breath.3

If the mind is distracted by sound again, repeat steps 3-4.

This technique is easiest when the sensation is repetitive since the mind is more easily drawn to things which it cannot predict. Once this starts to feel easy, you can start to intentionally bring in distractions in the following order:

Instrumental music: Remember, your goal is not to focus on the music, but to use it as a “distracting” factor. The goal is to turn the mind inward, not to allow it to settle on the music.

A TV show or YouTube video with words, or a podcast that you find boring or neutral: If you end up listening to the words for the whole time, the goal has been missed. Ideally, with practice, you would not be able to recall what was said except as a vague memory.

A TV show, YouTube video, or podcast with words, that you are interested in: This is especially challenging because the sensation activates a klesha (here, raag, or attraction). When a klesha is activated, attention is automatically drawn to it.

As with everything in Yoga, Pratyaahaar takes practice. At first, it can be frustrating, but this is the very reason that practice is important.

Don’t be hard on yourself. Simply notice your tendencies, and meet yourself where you are.

Over time, following the four keys to practice, your Pratyaahaar will improve, and you will be able to focus and keep a calm mind even in the most difficult of circumstances.

Until next time:

Try practising each of these techniques at least once to see what works best for you.

Once you have found a technique that works, practice it every day for at least 10 minutes, setting a timer.

Take notes to keep track of your progress, and to uncover your tendencies!

Next time: What is a sensation? More on Pratyaahaar.

Technically speaking, the chakras are in the the subtle body, not the physical body, but the association works just fine either way.

This method a way to smoothly transition into the next limb, Dhaaranaa. If your aalambanaa, or support, is not the breath, but a mantra, or something else altogether, you can bring your attention to it at this point in the technique.