How should I sit?

Aasana: Specific Postures

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

हठस्य प्रथमाङ्गत्वादासनम् पूर्वमुच्यते।कुर्यात्तदासनं स्थैर्यमारोग्यं चाङ्गलाघवम्॥Hathasya prathamAangatvaadAasanam poorvamUchyateKuryaatTadAasanam sthairyamAarogyam chaAngaLaaghavamFirst, Aasana is said to be the first limb of the Hatha Yoga.

Having done Aasana, [the Yogi achieves] steadiness, diseaselessness, and lightness of the limbs.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 1.17

In Raja Yoga - the path of meditation, which we are currently discussing - the goal of the third limb, Aasana, is to be able to sit still and comfortably for long periods of time. This is to be done in such a way that the Yogi’s mind is no longer distracted by the opposites such as heat, cold, comfort, discomfort, pleasure, pain, and so on.

The way to do this is by releasing prayatna (ie. effort) or sankocha (ie. tightness) throughout the body, such that the body can settle into a comfortable and stable posture.

Last week, we went over the fundamentals of this practice, as well as a few traditional methods to release sankocha, or tightness (aka praytna, or effort).

When it comes to meditation, however, not all poses are created equal.

There are some fundamentals which, if followed, allow the practitioner to access deeper states faster and more easily. In this week’s article, we will go over some examples of meditation postures, as well as a brief Hatha Yoga (ie. the typical postural Yoga you may find in a Yoga studio) exercise which will help to demonstrate the basics of how to target your practice.

As discussed last week, Hatha Yoga is a very important part of the process, and one can easily spend a lifetime perfecting postures, human anatomy, and how they affect each other. There is tremendous power to these practices, in terms of physical and mental well-being. However, while it may be helpful, it is not necessary to perfect Hatha Yoga in order to perfect your meditation practice. Furthermore, too much focus on Hatha Yoga can actually be detrimental to Raja Yoga if it leads to a stronger identification with the body.1

Meditation Postures

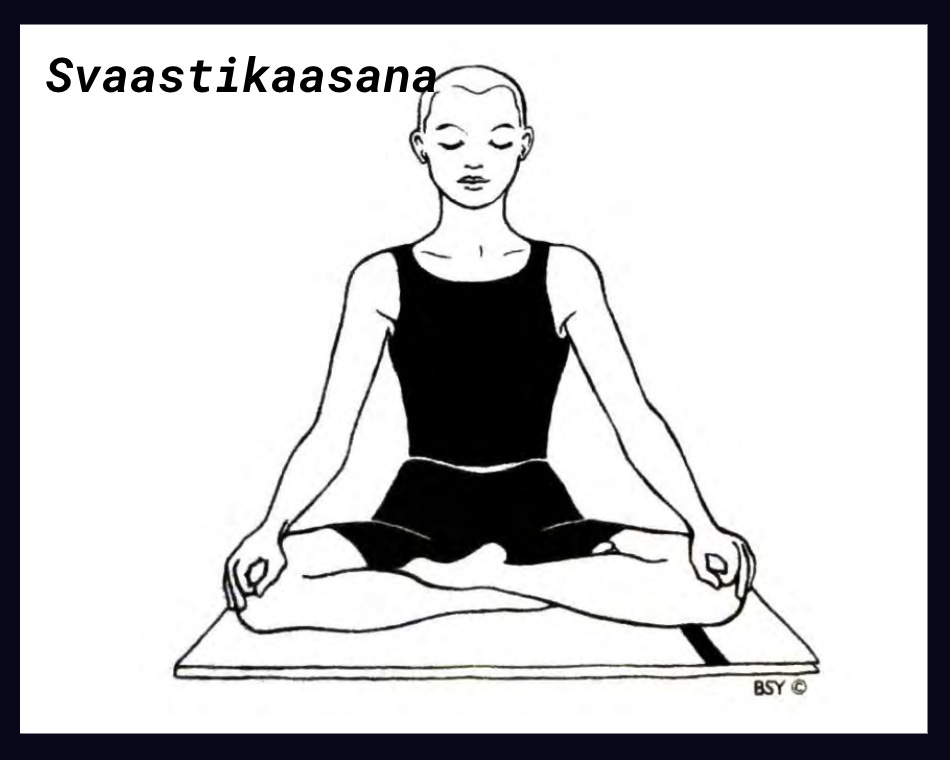

Traditional commentaries mention a number of specific postures that are especially conducive to meditation. Some of them are shown in the image below.

Vyasa (the foremost traditional commentator on the Yoga Sutras) names a total of eleven meditation postures in his commentary2, but we will focus on six in this article.

Padmaasana: The lotus pose

इदं पद्मासनं प्रोक्तं सर्वव्याधिविनाशनम्।दुर्लभं येन केनापि धीमता लभ्यते भुवि॥Idam padmaasanam proktam sarvaVyaadhiVinaashanamDurlabham yena kenaApi dheemataa labhyate bhuviThis is called Padmaasana [the lotus pose] - Destroyer of all Disease.

It is extremely difficult for most people. Only a few wise ones on this Earth can achieve it.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 1.47

This is widely considered to be the best posture for meditation.

However, it is a lot harder than it looks, and if done without proper preparation, it can lead to serious injury in the knees, hips, ankles, and lower back. This is especially true in today’s day and age where most of us spend a significant percentage of our time sitting in chairs, which leads to tightness in the hips and lower back.

Be careful: If you want to attempt this position, make sure to sufficiently loosen your hips first (this often takes years), and protect your knees by keeping your ankle at ninety degrees to your shin while in the posture.

Essentially, padmaasana involves placing the feet on the opposite thighs (ie. right foot on left tight, left foot on right thigh), while keeping the hips, chest, neck, and head in alignment.

As with any aasana, practice both sides equally to ensure balance. That is, first practice with your right leg above your left, and then with your left leg above the right. Over time, following the four keys to practice, the posture should become effortless. Then, it can be used for meditation.

Bhadraasana: The gracious/divine pose

भद्रासनं भवेदेतत्सर्वव्याधिविनाशनम्॥Bhadraasanam bhavedEtatSarvaVyaadhiVinaashanamThis is Bhadraasana - the Destroyer of all Diseases.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 1.54

This aasana is sometimes taught as the butterfly pose. However, while it is somewhat similar, the butterfly pose is known as moola-bandha-asana or baddha-kona-asana (these have slight variations), and differs from bhadraasana in that the toes are pointing forward.

For bhadraasana, start by kneeling, and sit down on your heels. Then, spread your knees as wide as possible, making sure to keep your head, neck, and chest in alignment.

Like Padmaasana above, it is also known as the “Destroyer of all Diseases.”

Siddhaasana: The pose of the perfected one

किमन्यैर्बहुभिः पीठैः सिद्धे सिद्धासने सति॥KimAnyairBahubhih peetthaih siddhe siddhaAsane satiWhen perfection can be attained through Siddhaasana [alone], what is the use in practicing so many other Aasanas?

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 1.41

This posture is considered to be one of the best for meditation. To start, sit on the ground in a cross-legged posture, and pull your left heel in until it touches your perineum (the space between the anus and the genitals). Then, left the right foot and place it above the left foot, such that the heel touches the pubic bone, directly above the genitals.

Then, sandwich the toes of the right foot in between the left thigh and left calf muscle, making sure the spine is erect, and the head, neck and torso are in alignment.

As with padmaasana, be careful with this posture, since it can lead to injury in the knees if not done with the appropriate preparation. Try it, by all means, but be aware of the risk.

Vajraasana: Thunderbolt/Diamond Pose

To sit in this posture, start by kneeling with your shins on the ground, and then sit down on your heels. Then, allow your heels to move apart, and sit in the pit created by them, but keep the big toes touching each other. As with all the postures, make sure that your head, neck, and torso are in alignment with each other.

As an aside, if you are ever having stomach pain or heartburn, especially after a heavy meal, try sitting in this posture for five to ten minutes.

Be careful: A possible contra-indication to this pose, especially for those with weak knees or a recently slipped disc, is that it may hurt the knees or the lower back. To solve for this, place a pillow in between the feet, and sit on the pillow while in this posture to reduce the pressure on the knees.

Svastikaasana: Auspicious pose

जानूर्वोरन्तेरे सम्यक्कृत्वा पादतले उभे।ऋजुकायः समासीनः स्वस्तिकं तत्प्रच्क्षते॥JaanoorvorAntare samyakKrtvaa paadaTale ubheRijukaayah samaaSeenah svastikam tatPrachkshatePlace both the soles of the feet on the inner side of the thighs, and sit evenly with a straight body. This is known as Svastika.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 1.19

Start by sitting cross-legged on the floor. Then, place your left foot between the right thigh and knee, hiding the toes, and place the right foot between the left tight and knee (also hiding the toes).

Dandaasana: Staff pose

This one is a little different from the rest in that it requires more core strength, and allows for arm support. Start by sitting down and stretching the legs all the way in front of you, with the sides of feet touching each other in complete alignment. The hands should rest by the sides of the body with the fingers slightly apart.

Or whatever is comfortable

स्थिरसुखं यथासुखम् ॥SthirSukham yathaaSukham[Or] whatever [posture results in] stability and comfort.

- Vyasa’s commentary on Yoga Sutra 1.46

In Vyasa’s commentary, he mentions that aside from these specific postures, any posture that allows for stability and comfort is an acceptable posture for meditation. There is no need to force the body into the poses mentioned above in order to meditate, although they are certainly helpful.

The main thing is that the head, neck, and torso should be in alignment with each other, and that there should be complete comfort and stability in the pose.

If you are able to sit without back support, that is ideal, since it allows the lungs to expand backwards, allowing for fuller, deeper breaths, and keeps the mind alert.

P: What about walking meditation?

Jogi: In Yogic terms, what you call “walking meditation” is a form of eka-tattva-abhyaas - the practice of focusing on one thing at a time. This is an extremely useful preliminary practice, but is not a substitute for seated meditation. The reason for this is that while walking, the mind is drawn out to many things such as the space around you, the placement of the feet, any obstacles in the path, and so on. When sitting, on the other hand, the mind is free to let go of the external world and move inwards.

P: What about meditation while lying down?

Jogi: Yes, this is possible, and is known as paryanka or shavaasana (bed pose or corpse pose). However, it is not recommended unless there is no other possible pose, since it may lead the tamasic mind to fall asleep, and the rajasic mind to dream. Then, if you are not honest with yourself, you will emerge thinking that you had a deep meditation session when in fact you just fell asleep.

Meditation requires the mind to be extremely alert, but lying down can induce feelings of tiredness. You can try it for yourself and see if it works for you, but make sure to be completely honest with yourself about what you experience. However, sitting with the head, neck, and torso in complete alignment, and without a rest for the back, is the best way to ensure that the mind stays alert throughout.

For most of us, sitting in the poses above can be quite difficult. Try sitting cross-legged on the ground and see if you are able to keep your back straight. Aside from a few lucky ones, for most of us, the back starts to hunch forward, and the knees start to rise upward from the ground.

Trying to sit like this for a long period of time will cause fatigue in the hips and psoas (and perhaps other muscles as well), since the muscles have to continuously work against gravity to keep the body in an upright position.

In order to avoid this, try placing your buttocks on top of a cushion or block such that the knees are below the level of the hips. Once the knees drop below the hips, you will notice that you are able to rest with your back completely straight. Additionally, placing a folded blanket below the knees is helpful to avoid injury from prolonged contact with a hard floor.

Now, you can try to place your legs in any of the postures above that work best for you. Whatever posture you choose, the head, neck, and torso should be in alignment, and it should feel as though the head is floating, without any muscular strain throughout the body.

Fundamentals of Aasana practice

आसनानि तु तावन्ति यावत्यो जीवजातयः।एतेषामखिलान् भेदान् विजानाति महेश्र्वरः॥Aasanaani tu taavanti yaavatYo jeevaJaatayahEteshaamAkhilaan bhedaan vijaanaati MaheshvarahThere are as many Aasanas as there are living beings. Their definitions and distinctions are known to Shiva [the Great Ishvar].

- Goraksha Shataka, 8

According to the Goraksha Shataka, Shiva taught humanity as many aasanas as there are species in this world. Out of all these, 84 of them are selected as the best for practice. Out of these 84, two of them are considered by the author of the Goraksha Shataka to be the most important - padmaasana and siddhaasana, both of which are meditation postures.

The traditional method of Aasana is to hold a specific posture for a substantial period of time, rather than “flowing” from one posture to the next in quick succession. In doing so, the Yogi can pay close attention to various parts of the body, making micro-adjustments to perfect the posture over time. This is not to say that there is anything wrong with any sort of “flow” Yoga, which also has great benefits for the body, but is a newer innovation.

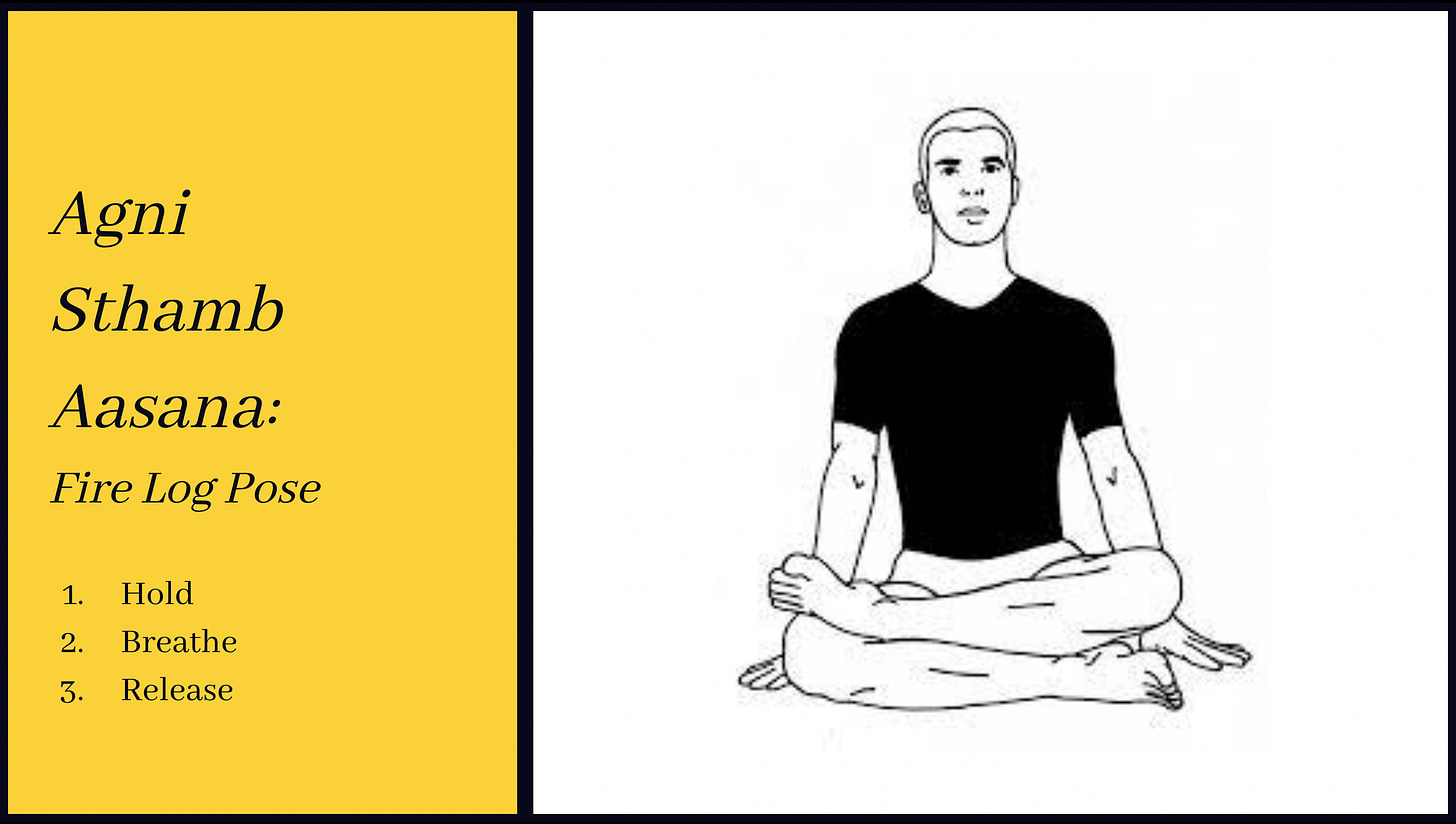

In order to get the most out of a given posture, there are three fundamentals that should be kept in mind:

Hold

Breathe

Release

We will go over these fundamentals using one posture as an example, but these can be extended to all Aasanas.

The example: Agnisthambhaasana - Fire Log Pose

Sit down cross-legged on the floor, and place one ankle on the opposite thigh. Make sure the ankle is resting on the thigh - not the foot.

Take the foot that is on the ground and push it slightly forward so that your shins are completely parallel with each other

Don’t place your hands on the ground as in the image. Rather, allow them to rest on your thighs.

Is one knee floating in the air, or are you able to get it to touch the ankle on the ground?

Now try the opposite side and notice any imbalance. Was one side more difficult than the other?

If your knee was floating in the air, this posture is a perfect example for you. However, if you are extremely flexible and this was not a problem, you can try bending forward to get a deeper stretch.

Be careful: Make sure that your ankle is resting on the opposite thigh - not the foot - otherwise you may hurt your ankle. Also, try to keep both your feet at ninety-degrees to the shin to protect the knees. If you have recently had joint pain, a slipped disc, or surgery, do not try this exercise. Finally, if you have a knee injury, do not try this exercise.

Ok, now to the three fundamentals:

Hold

Breathe

Release

Hold

As you sit in this position, count the number of full breaths (in and out together counts as one). Each time you practice the pose, try to increase the number of breaths by at least one, if not more. You can start by counting to twenty complete breaths per side.

You can also do this by setting a timer to three minutes per side.

Make sure to practice both sides equally, regardless of the pose you choose to practice.

Breathe

There is a specific breathing technique that will allow you to release the sankocha (tightness) with greater ease - it is called ujjayi, or victorious breath.

Try this: Breathe in through your nose, and then, when your lungs are filled with air, open your mouth and breathe out while making a continuous “hhhhh” sound. If this is difficult to follow, try whispering “Om” for as long as you can, as loudly as you can.

This kind of breathing increases vagal activity, which relaxes both the body and mind by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system. This results in reduced blood pressure and heart rate, leading to a feeling of relaxation if done for sufficient time.

Try doing this as you sit in the position, counting the number of times you exhale in this way, and notice the parts of your body where you feel the tightness the most.

Note: Even if you’re not trying the poses right now, try doing this breathing technique for at least ten repetitions, and notice how you feel.

Release

Finally, as you are holding and breathing in this way, try to completely relax the parts of the body where you feel the sankocha. It should feel like you are leaving that part of your body completely limp, gradually letting go of any residual “holding on” with every exhale. There is no force involved - rather, it is a complete and utter release of effort.

Now that you have done this for one side, switch over to the other side and repeat the exercise. Notice how the knee dropped closer to the ankle in just one sitting!

Now what?

Carefully notice the tightness in your body, and focus your Aasana practice on these areas. Each body is different and has different tendencies. Pay careful attention to your body so that you can direct your own practice. Alternatively, one can always seek the help of a teacher at your nearest Yoga studio or online.

The practice of Aasana has great benefits for the body and mind, but in terms of Raja Yoga, it is only one step on the way to a much larger goal. There is no need to perfect every posture or become a gymnast in order to move further inwards. Simply practice enough such that you are able to keep the body still and comfortable for long periods of time. This way, when you close your eyes for meditation, you can feel as though the body has “dropped away”, and the mind is free to move further inwards, towards the Self.

Until next time:

Experiment with the postures mentioned above to find a position that works for you (ie. where you can sit still for an extended period of time). The body should be stable and comfortable, and the head, neck, and torso should be in alignment. If you need a cushion, use one (you can find meditation cushions, called zafus, online). If you need a chair, that’s fine too. Just make sure to find one position and stick to it. This posture will be used in the coming weeks as we go deeper into the next few limbs of Yoga. Don’t worry too much if your legs fall asleep3 - even the Buddha was known to have rubbed his ankles after meditation!

Optional: If you have a regular Aasana practice, try to use the three fundamentals (ie. hold, breathe, release) with each pose, and take notes to see how your practice develops over time.

Next time: Pranayaam: The fourth limb of Yoga

The style of Yoga known as Iyengar Yoga, pioneered by the great BKS Iyengar, uses postures as the object/mental support for meditation. While this is unconventional, and is a very recent innovation (Iyengar died in 2014), it certainly falls within Patanjali’s guidelines where any object can be used as a mental support for the later limbs.

The eleven aasanas mentioned by Vyasa are padmaasana, veeraasana, bhadraasana, svaastikaasana, dandaasana, sopaashraya, paryanka, krauncha-nishaadana, hasti-nishaadana, ushtra-nishaadana, sama-samsthaana.

Through targeted Aasana practice, this will eventually stop happening, and you will be able to sit for longer periods of time without your legs falling asleep.