What is a sensation?

Vrittis, Pratyayas, and how Karma projects your own personal world

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

One night, Mulla Naseeruddin was seen stumbling around in the dark outside of his house. He would stand underneath a street lamp and bend over, as if searching for something. After a while, he would stand up, walk over to the next street lamp, and repeat the same process. A kind passerby saw Mulla Naseeruddin repeat this a few times, and asked him, what he was looking for. Mulla Naseeruddin replied that he was searching for his house keys.

The passerby asked him where he had last seen the keys, to which the Mulla responded, “Inside my house of course!”

Confused, the passerby asked, “Then why do you search on the street?”

Standing upright, Mulla Naseeruddin looked the passerby straight in the eyes, and said, “Isn’t it obvious? There is so much more light here!”

We spend our lives in search of objects that may relieve us of our unease. We feel dissatisfied, uncomfortable, like something isn’t quite right. For most of us, we have learned to ignore this feeling as a part of life, the “human condition.”

We know that there will be ups and downs. Sometimes we will be happy, other times we will be sad. We know that Death is coming for all of us, and yet we mosey about as though we are immortal. We push down this knowledge - suppressing it - as though hiding from it will solve the problem.

The most we may hope to get out of life is money, power, happiness, perhaps community, love, a family, or to make a name for ourselves. Maybe we want that elusive thing called “meaning” or “purpose” or “fulfilment.” We struggle to achieve these objects, enduring suffering along the way, and when we finally get them, we find that we are disappointed, hankering for something different.

This game plays out at the scale of our day to day life, but it’s the same game as the years go by. This constant thirsting, or trishnaa bleeds into the very fabric of our society. We have built entire structures, over generations, to enable this very game to be played.

We suffer as we want, we suffer to achieve, we suffer once the sheen of achievement wears off, and then we suffer as we start the cycle anew.

We search outside of ourselves for a satisfaction that never comes. We are all like Mulla Naseeruddin - searching for the key to our fulfilment outside of ourselves, because that’s where the light is.

P: What’s wrong with that? Why can’t I go on looking for objects?

Jogi: There is no authority to tell you what to do. Search for happiness however you please. Just know that satisfaction from objects (aka vishay-aanand) is limited, temporary, and unsustainable.

P: So then were can I find lasting fulfillment?

Jogi: By Knowing your Self as you truly are.

P: Why is the “K” in Knowing and the “S” in Self capitalized?

Jogi: Normally, when you think of “knowing”, you think of objects. This Knowing is a different sort of knowledge, just as a lamp illumines itself in a different way from how it illuminates objects around it. This Knowledge is not some new knowledge to be gained, rather, it is to be uncovered.

As for the Self, normally we think of “self”, we think of the body, perhaps the mind, the personality, memories, identities, or some mixture of these. Here, the Self specifically refers to That which is beyond objects, within which all objects appear, exist, and into which they disintegrate just as water is that which is beyond waves, but within which all waves appear, exist, and into which they finally disintegrate.

P: How will knowing the Self give me lasting fulfillment?

Jogi: We feel uneasy and unfulfilled because we feel limited in time and space, and this limitation breeds fear. This fear manifests at different levels of intensity as our day-to-day discomfort, or at its highest, as a fear of Death. Knowing your Self as unlimited in time and space, there is nothing more to be known, achieved, or otherwise experienced. There is no pressure to “do” anything, since it is clearly seen that all objects - including thoughts and ideas - are mere imaginations - groupings of individual sensations, spontaneous and perfect. Just as one does not see imperfections in the shape of a cloud, or desire for it to move in one place or another, such a person sees the body-mind as another happening of nature - perfect as it is.

P: Ok, but what does this have to do with Yoga? Weren’t we just discussing Pratyaahaar?

Jogi: As we have discussed, the Self cannot be seen, touched, heard, tasted, or smelled. It is beyond the senses. The journey of Yoga is a journey to the Self, and so it follows that to find this “Self”, we must go beyond our senses.

Over the past few weeks, we have been discussing Pratyaahaar, or sense withdrawal - the fifth limb of Yoga, and the precursor to meditation. Pratyaahaar manifests “off the cushion” in our day to day lives as the Yamas and Niyamas, and “on the cushion” as specific techniques such as body scanning, mindfulness of the senses, and gently “letting go” of the ability to sense and act.

One symbol of Yoga is the turtle.

Steady and calm, it is able to withdraw its limbs into its shell. Similarly, the Yogi, steady and calm, is able to withdraw the senses into the mind at will.

This limb of Yoga, often forgotten, is a key to deepening meditation, as well as to remaining calm and centered in day to day life. Without it, meditation is challenging, and the mind can be difficult to control.

इन्द्रियाणां तु सर्वेषां यद्येकं क्षरतीन्द्रियम्।तेनास्य क्षरति प्रज्ञा दृतेः पादादिवोदकम्॥Indriyaanaam tu sarvEshaam yadiEkam ksharatiIndriyamTenaAsya ksharati pragyaa driteh paadaadIvaUdakamIf even just one of all the indriyas starts to ooze outward, all the wisdom oozes out, just like all the water oozes out of a leather bag from a single hole.

- Manusmriti 18.2.99

Any time we are pulled out by even a single sense, if our outward tendencies are strong, the mind is very difficult to reign back in. This is why Pratyaahaar is important. This can be compared to how the smallest hole in a container leads to all of the water spilling out.

On a deeper level, Pratyaahaar helps us to tilt the mind inward, opposing its natural outward tendency. This helps to bring the attention towards the Self, which cannot be grasped by the senses. Otherwise, if the outward tendency is followed, the attention will flow towards objects - gross and subtle - moving the Yogi away from the goal.

What is a sensation?

In Yogic terms, there are a total of five jnanendriyas (aka buddhendriyas), or sense organs. Each of these can modify in particular ways, just as water can modify in particular ways to form waves, or as clay can modify to form a pot.

Ultimately, all waves are just modifications of water, and in the same way, all objects are just modifications of the five senses.

This turns our conventional thinking on its head, so take a moment to let it set in.

Normally, we think that there are objects, and our senses perceive them. In Yoga, however, the objects are made from the senses, like a pot is made from clay.

Everything that you see around you, including these words, is nothing but your senses dancing in a particular pattern. We name these patterns, especially when patterns between senses match up (e.g. if you can both touch and feel an object), and this is how the Universe is projected.

For more on this, take a look at the article on how the senses create the world here.

Now let’s get more specific.

The senses don’t modify into complete objects. Rather, they modify into momentary happenings, kind of like pixels on a screen. These pixels, or momentary happenings, are called pratyayas (प्रत्यय, pronounced pruh-tyuh-yuh).

Just like we mentally group pixels on a screen to perceive images, we group these pratyayas based on our own conditioning (aka samskaaras). These groups of pratyayas are called vrittis, or waves.

P: Wait a second. How can the groups be based on our own personal conditioning? Aren’t the groupings real in themselves?

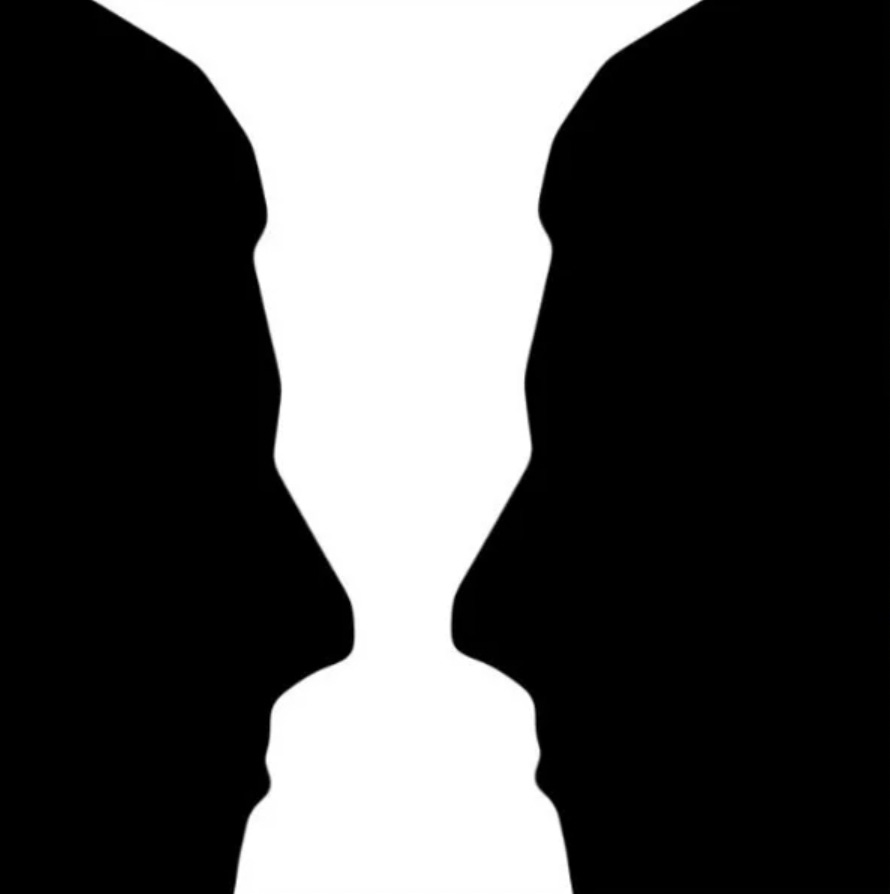

Jogi: Consider this image. What do you see?

P: I see two faces looking at each other. So what?

Jogi: Look again, can you see a white vase?

P: (pauses) Yes!

Jogi: Now consider, why did you see the faces, and not the white vase?

P: Because the background of this text is white, and so my mind automatically interpreted the white as background.

Jogi: Exactly. The white colour of the background created an imprint - a samskaara - in your mind, of the form “white equals background”. You then saw the image through the lens of this samskaara, and automatically assumed that white was the background. This brought the black to the foreground. As a result, you saw faces rather than a vase.

For someone else, perhaps viewing this in dark-mode, or with a different set of samskaaras, they may see the vase before the faces. In much the same way, we group pratyayas together to form vrittis, and so filter our entire experience of life, based on our own karma.

P: So is it two faces or a vase?

Jogi: It is neither - it’s just a group of sensations, and you give it meaning based on your own karma.

To summarize this, our senses modify into pratyayas just as water modifies into waves. We then group these momentary pratyayas into vrittis based on our past conditioning (aka karma).

P: How is this relevant to Yoga?

How sensations relate to vrittis

The definition of Yoga is:

योगश्र्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः॥YogasChittaVritti NirodhahYoga is the mastery of the vrittis in the chitta.

- Yoga Sutra, 1.2

The source of vrittis is the activation of the senses. In addition, the closer the vritti is to the activation of a sense, the grosser it is.

For example, if I am looking at a rabbit right now, the vritti is extremely gross, or heavy (स्थूल, sthoola) . It feels “really real.” On the other hand, if there is no rabbit around, but I try to recall a rabbit from my past experience, the memory or visualization feels “less real.” In Yoga, this kind of mental movement is described as more subtle, or lighter (सूक्ष्म, sookshma), than the direct perception.

There are even more subtle kinds of mental movements, like the ahamkaar (the “I-maker”) and the buddhi (the decider/the intellect). These are also based on sensory involvement, but are further removed, and are thus even more subtle, or sookshma, than imagination and memory.

The definition of Yoga is the mastery of the vrittis, and so it may be helpful to recap the five types:

All mental happenings are one or a combination of these five categories. Of these 5 types of vrittis, four of them are generated by the contact of the senses with their respective objects, and one is generated by the absence of contact.

The first, pramaan, or evidence, is based entirely on senses having contact with gross objects. You see a tree, and you know it’s a tree. Or, you see smoke, and you infer fire. Or, you hear about an event, and you develop a knowledge of that event.

The second, viparyay, or error, is also based on contact with gross objects, but includes an aspect of subtle objects. For example, you see a rope in semi-darkness, but think that it is a snake. The mental image was a snake, but it is based on the sight-sensation of the rope in semi-darkness.

The third, vikalp, or imagination, is also based on sensations, but manifests as subtle objects. Your imaginations happen in your mind, but they are of objects. Your inner eye “sees” objects, your inner ear “hears” sounds, etc. Remember - in Yoga, the senses are not the external organs (ie. the eyes, the ears, etc.), but the power of sight, hearing, and so on. When you see something in your mind, the indriya of sight is still active.

The fourth, nidra, or deep sleep, is based on the absence of both gross and subtle sensation. You once had sensation, and then you didn’t, and so you can compare the two. Absence only has meaning in relation to presence, and so nidra is also based upon sensation.

Finally, the fifth, smriti, or memory, is also based on the contact of senses with their respective objects, except that there are two moments of contact, separated by time. Consider an example of remembering a quote that you once heard. You only remember it because you heard it at some point. That is the first contact. Then, at the moment of memory retrieval, you hear the quote again, but within your mind. This is the second moment of contact.

As you can see, the senses are the very basis of the five vrittis, and so disconnecting the senses through Pratyaahaar provides a major boost forward towards the goal of Yoga.

Sensory involvement, dukkha, and action

Consider the last action you did. Perhaps it is reading these words, picking up your phone, or walking to a quiet place to read. What led you to act?

Notice, every action that “you” do is a reaction to a feeling of discomfort, whether mild, mediocre, or strong.

You read because there is a sense of discomfort in not reading, and so you act to fill that gap, just as air rushes to fill a vacuum. You shift in your chair because of a physical discomfort in sitting still. You breathe because of the desire to avoid discomfort of not breathing.

Even thinking is the result of a discomfort with mental silence, a desire to resolve a thought (another discomfort) or a feeling of being “unproductive” or mentally empty.

All desire is a product of discomfort, and all action is a product of desire. This discomfort, known as dukkha, is the basis for all our actions as the bodymind.

The subset of the actions that we consider voluntary are especially interesting. We consider ourselves to be acting, when we are, in fact, simply reacting to mental movements based on sensory input, whether subtle or gross.

A pramaan-vritti of hunger arises, and so the bodymind gets out of the chair and moves towards the fridge. Then the ahamkaar says “I did it”. In this way, sensation and so-called “voluntary” action are two sides of the same coin.

The ultimate cause of this discomfort, of dukkha, is avidya. Avidya can be seen as the grouping of the momentary pratyayas into vrittis in such a way that we take the vrittis seriously - as “real” objects. These vrittis, as we saw in the section above, stem from sensory involvement, and so abstracting sensory involvement (aka Pratyaahaar) allows us to temporarily stop dukkha.

Remember, abstracting sensory involvement is not suppression. It is more similar to how the wipers are abstracted from attention when driving in the rain.

P: Is sensory abstraction, or Pratyaahaar, enough to stop dukkha altogether?

Jogi: No. It is only a step along the way.

P: Why not? If dukkha is based on vrittis, and vrittis are based on sensory involvement, shouldn’t abstracting sensory involvement be sufficient to stop dukkha?

Jogi: Dukkha is based on avidya. Avidya can be seen as the grouping of pratyayas into vrittis, and taking the objects they represent to be real. Pratyaahaar may stop pratyayas, but the moment they return, the mind will once again start grouping them into vrittis, thus starting the cycle of dukkha again.

P: Then what’s the point of Pratyaahaar?

Jogi: It allows us to temporarily relieve our dukkha, so that the mind is no longer engaged with thought. This allows the Yogi to delve further inward, and explore without distraction.

In summary

The objects of the world, including the happenings within our mind, are groupings of pratyayas, just as images on a screen are groupings of individual pixels. The groups are not real in themselves, rather, we mentally group these pratyayas based on our past conditioning, or karma. We then takes these groups of pratyayas as real. As a result, we suffer (aka dukkha).

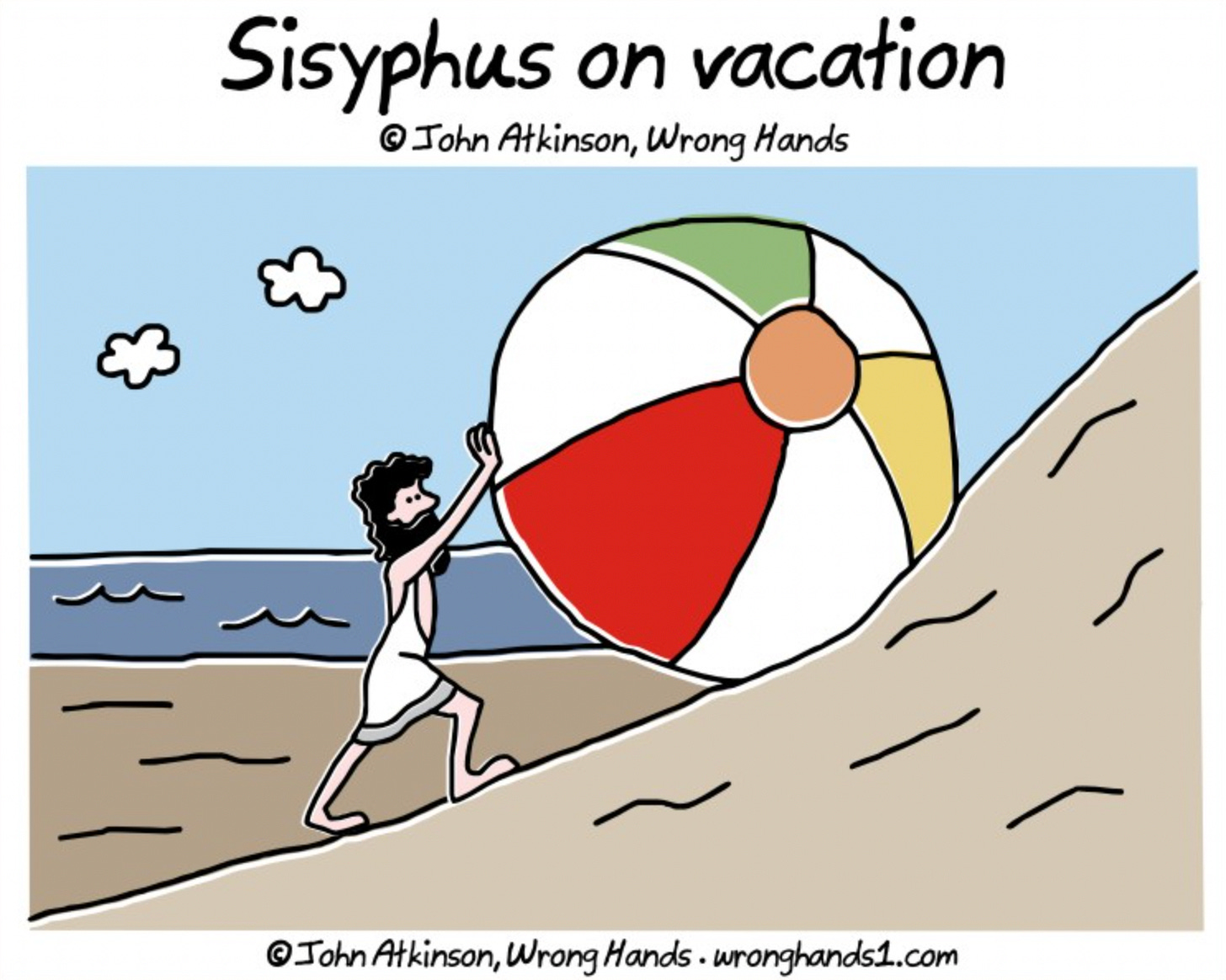

The bodymind is continuously acting, shifting, and changing, to relieve dukkha, and the ahamkaar takes credit for a subset of these actions, thus creating more impressions (aka samskaaras) in the mind. However, there is no action that can permanently relieve dukkha, and so karma is an infinite, sisyphean, cycle.

The Yogi, however, is able to withdraw their senses using the methods of Pratyaahaar on and off the cushion. By withdrawing the senses, vrittis are seen as momentary pratyayas, and can be let go of just like a driver “lets go” of the windshield wipers in order to focus on the road. Once this happens, the mind is temporarily relieved of dukkha, and the attention can move further inward without being drawn out by objects.

Until next time:

Notice the slight discomfort that precedes your actions today. For example, if you eat, mentally note that you chose to eat food due to hunger, or desire, and notice the nature of that discomfort. Was it severe, medium, or mild?

Try to notice the lens through which you view particular situations, and how this view is coloured by impressions (aka samskaaras) in your mind. How might someone with a different set of samskaaras view the same set of circumstances?

Take notes!

Next time: Levels of Pratyaahaar