How we lie to ourselves: Part II

The Four Confusions: Suffering and Non-Self

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

While the various techniques in Yoga certainly help to make the mind feel calmer, less stressed, and more joyful, these are just side effects. The ultimate goal of Yoga is nothing short of the complete cessation of all suffering (ie. complete fulfilment), and, if reincarnation is a part of your worldview, freedom from the cycle of birth and death.

This may sound philosophical or theoretical, but it is already your goal in life, whether you know it or not.

We spend our lives trying to reduce our suffering and increase our happiness in all sorts of roundabout ways - through money, power, relationships, sense enjoyments, and so many more. But every time we “get that thing”, another thing pops up in its place, and we start to strive after that, in an infinite game of whack-a-mole.

You wanted a million dollars, so you suffered tremendously, and got it. Now it’s not enough, and you want five million. You get that, and you realise that money wasn’t the thing you were after, maybe it was power. Then you get that, and, still unfulfilled, you start to think that maybe you wanted good relationships with people. You go make some friends, but now you want love. Maybe find a significant other, get married, have children, but now you realise that that isn’t fulfilling you either. There is always something more to be had, and running after these phantoms is how we spend our lives, until the body runs out.

This constant hankering is called dukkha. As mentioned in a previous article, the word dukkha is derived from the prefix du, which means bad, improper, not good, etc., and the root word kha which means space. It conjures the image of a chariot where the wheel doesn’t quite fit the axle, resulting in a bumpy ride. This bumpy ride is the nature of life as a jiva (an individual sentient being). Our thirst for happiness and fulfilment is insatiable, and we suffer as a result of it.

आवृतं ज्ञानमेतेन ज्ञानिनो नित्यवैरिणा | कामरूपेण कौन्तेय दुष्पूरेणानलेन च ॥Aavritam jnaanamEtena jnaanino nityaVairinaaKaamaroopena Kaunteya dushpoorenaanalena chaEven for the wisest people, the perpetual enemy called Desire veils the Knowledge [of the Self], like an insatiable fire.

- Bhagavad Gita, 3.39

Yoga provides a systematic mechanism to fulfil this constant thirst - all it takes is practice - no blind faith involved. In fact, don’t take my word for it, and don’t just trust the traditional texts, commentaries, or any other authority either - try it for yourself and see if it works for you.

The method is to remove avidya, the primal ignorance, which is the root cause of our suffering. In order to do this, we must first understand what avidya is.

Last time we began a discussion on how avidya manifests in our lives as four deep-seated confusions:

Confusing the impermanent to be permanent

Confusing the unclean to be clean

Confusing suffering to be pleasure

Confusing the non-self to be self

We went over the first two confusions last week, and so this week we will go over the third and fourth on the list.

Confusion #3: Confusing suffering to be pleasure

All pleasure is surrounded by what is called the “threefold suffering.”1 The word used for suffering in the Yoga Sutras, and most other texts from Indic traditions, is “dukkha”. “Dukkha” does not quite have the same connotation as the word “suffering” in English, although it is often translated this way. As described above, it is more like a constant sense of hankering, unease, and discomfort - a bumpy ride - rather than the searing pain that the word “suffering” conjures up. For this reason, we will use the term dukkha itself rather than the word “suffering.”

Consider any pleasure - it could be a vacation, a chocolate chip cookie, a nice cold drink on a hot summer’s day, or something bigger like getting a promotion at work, winning a coveted award, or buying a house that you always wanted.

Now think about the time before you got that pleasure. It was filled with some degree of longing (dukkha), and effort to get it (more dukkha).

Ok, then it all worked out and you got it. Great! But not really. It is impermanent, and you know it, so you are afraid that it won’t last (dukkha), you make efforts to extend it (more dukkha), and perhaps it wasn’t up to your expectations (even more dukkha).

Finally, the pleasure is over. This time is filled with longing for the pleasure to repeat (dukkha), the effort to repeat it (more dukkha), and the lamentation for its loss (even more dukkha).

You can apply this to any pleasure at all. All pleasures are surrounded by this threefold dukkha - before, during, and after - like honey mixed with poison.

Like with the other aspects of avidya, we don’t want to admit our confusion, even to ourselves, and so we spend our lives running after pleasure, only to exacerbate our own suffering. On the surface claim that we are enjoying ourselves, finding meaning in our work, our relationships, and our families, when all the while, deep down, there is a constant sense of unease that we are deeply afraid to face.

Yam pare sukhato tadaraiyaa aahu dukkhatoWhat others call pleasure, [the Noble ones] know as suffering.

- Sutta Niptata 3.12 (765), Gautama Buddha

If this seems like too much to contemplate, this same confusion also rears its head on a more surface level when it comes to pleasures with obvious negative consequences.

Consider a friend who had a lot to drink the night before, complaining about their hangover and swearing that they will never touch alcohol again. They suffer after the pleasure is over, but it is highly likely that they will repeat the experience again.

On the other hand, for one who has noticed the dukkha in the apparent sukha (happiness/a smooth ride - the opposite of dukkha), they will notice the future suffering in the moment itself. This person is much more likely to actually hold off on drinking enough for them to suffer later.

“Even in a state of pleasure, the Yogi is afflicted by the dukkha [that manifests in] change, anxiety, and habituation…

…Others give up the pain they have again and again taken upon themselves … and again take it upon themselves after repeatedly having given it up. Such people are all-round pierced through by avidya, possessed of a mind full of kleshas, following in the wake of the “I” and “mine.””

- Vyasa, Vyasabhashyam on Yoga Sutra 2.15

This is true for any pleasure - consider a person trying to lose weight. They may eat a bunch of unhealthy food, only to regret it later when they start to see their weight increase, or when they start to see their health deteriorate in some other way. Just like in the example above, they suffer after the pleasure is over, but you, and everyone else, know that it is highly likely that they will repeat the experience again.

On the other hand, for one who has noticed the dukkha in the apparent sukha of the greasy food, they will notice it in the moment itself, and are much more likely to hold off on eating that kind of food again.

The reason for this is that every time one indulges in a pleasure, it creates an impression in the mind to repeat that pleasure. Similarly, with aversion - every time one indulges in avoiding an unwanted situation or object, it creates an impression to avoid that situation or object again. These impressions make it more difficult to hold off from following those habit patterns the next time.

Said another way, these mental impressions (called samskaaras) perpetuate our constant hankering to run towards pleasure and away from pain. It is like we are trying to put out a fire, but instead of pouring water, we are pouring fuel. This is how we tie ourselves up in the mire of avidya.

Note: To be clear, this is not to say that pleasure is bad or “unholy” in any way, but rather to face the fact that what we usually call “pleasure” is just suffering in disguise. There is no compulsion to do anything about it. Rather, just like with the other confusions, it is simply a matter of noticing the facts.

Confusion #4: Confusing the non-self to be Self

This confusion runs deeper, and is at the root of the other three. It can be broken down into three aspects. These are not three different interpretations - rather, they are three ways to look at the same phenomenon:

Confusion of the Self with the functions of body and mind

Confusion of Self with the contents of body and mind

Veiling and Projection (aka ajnaana)

Aspect #1: Confusion of Self with the functions of body and mind

We consider ourselves to be the body - but only sometimes.

This confusion often manifests itself through language - sometimes we say “I am thin” or “I am tall”, but other times we say “this is my body” or “my back hurts” as though the body and its parts were possessions of a different “you” floating in there somewhere. We even apply this to the mind, saying “my mind is restless” (as though it were a possession, like “my phone” or “my clothes”) but also saying “I am happy” or “I am angry” as though the mind were identical with you. We are not clear on this fundamental aspect of our own being - sometimes these objects are you, and sometimes they are not.

To quote Adi Shankaracharya,

किमज्ञानमतः परम् ॥kimAgyaanaMatah paramWhat greater ignorance can there be!

- Aparokshanubhuti, 17-21

We notice that the body is changing, and that we are the witness of the changes. We also notice that we are conscious, while the body is inert matter. We even notice that we can see, hear, taste, touch, and even smell our bodies in the same way that we sense other objects in the world around us. In these ways it becomes clear that the body is an object that is different from You, but, due to the body’s persistence in our experience, and due to the fact that we can sense other objects through the body, we start to identify with it. However, if you consider it closely, you will notice that not only is the body an object in your experience, the sensations are too.

We can also apply this to the mind - the mind is constantly changing, and you are the witness of those changes. The mind is an object, You are the subject. The mind is more “external” to You. In this way, we can see that the mind is also just an object in our experience, but we are confused about whether to identify ourselves with it or not.

Through the practice of meditation, we can start to clearly “objectify” the body and mind in this way, noticing that they are “not Self”, and ceasing to identify with them.

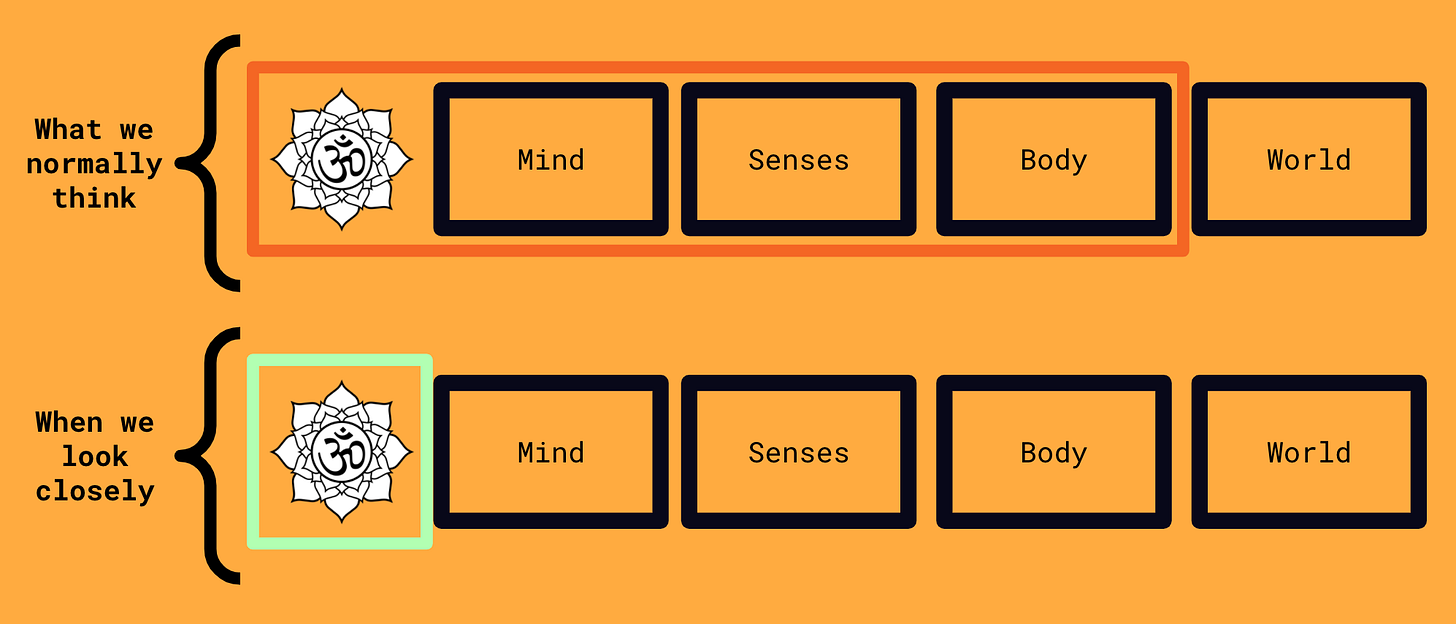

To make this clearer, consider the diagram of the 25 Tattvas below.

Normally, we consider everything in the yellow box to be “self”, and everything outside it to be “non-self” when in fact, the intellect, ego, mind, and senses are all objects that You, the Purusha, witness. These are the “components” or “functions” of body and mind, and the first way this confusion manifests is as a confusion of Self with these components - sometimes it is me, other times it is not me.

For more detail on this aspect, you can take a look at the article on the Purusha here, where we go over a Vedantic method called Drg Drishya Viveka (the discernment of the Seer and the seen).

Aspect #2: Confusion of Self with the contents of body and mind

In the first aspect, above, we are confusing the Self with the components or functions of body and mind. However, it doesn’t end there - in our ignorance, we go so far as to confuse ourselves with their contents and characteristics as well!

To make this clear, consider a time that you were asked to introduce yourself. What did you say?

“Hello, my name is so and so, I am so many years old, this is my job, I am from this place, these are my accomplishments, these are some things I like or don’t like, this is where I went to school, this is what I studied, this is my family.”

- You, at a networking event not too long ago

Now if you think about this carefully - none of these things are actually You. Your name is a convention given by your family. Your age is the time since the body came out of your mother’s womb. Your job is a series of tasks or ideas that your mind spends time thinking about, and for which the body-mind complex is provided material compensation in return for that service. Your home town is a location where the body has spent time, and of which the mind retains more memories than other locations. The things you like or don’t like are colourings (kleshas) on mental happenings (vrittis) based on past conditioning, and so on.

When you look closely, you can clearly see that anything you may use to describe yourself is just some combination of events, locations, memories, and ideas, pertaining to the body, the mind, and their components. But all these events, locations, memories, and ideas are just objects in your experience. You are just the witness of all of them.

This is as silly as if you were to observe a flower for an extended period of time, and then start to think that you are that flower. But, because of how we are socialised, we don’t see it that way, and as a result, we suffer.

Note: To be clear, this is not to say that these identities don’t have any value - of course they do. The set of memories in one mind are (mostly) unique, and we use this uniqueness to distinguish it from other minds. The problem is when we start to confuse ourselves as identical with that set of mental contents.

Depending on the strength of this confusion, we get upset when the objects deteriorate (since all objects, including memory, are impermanent), and we may even get angry if we feel that the objects are under attack! Nationalist movements around the world are a great example of this - people feel like they are Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, White, Black, Brown, Liberal, Conservative, etc, when these identities are nothing but bundles of memory and ideas in their experience.

Note: Again, this is not to say that identity has no value, or is not important - identity certainly shapes experience, and labels are convenient for communication. The problem is when we start to take the labels seriously.

This aspect of the self/non-self confusion often goes a level deeper where we start to confuse ourselves with our internal monologue.

There is a voice in your head reading these words, but that voice is not you. Notice closely, you are listening to the voice - there is a separation between you and the voice. When you stop reading this, the voice may start to speak about other perceptions, memories or imagination. Sometimes, the voice may turn into images or other symbols, but that voice, and the speaker of that voice are objects in your experience (specifically the manas, the subtle power of speech, and the subtle power of hearing, listening to the tanmaatra of sound). The voice in your head is not You, but we often take it to be so.

Ok - so we confuse the Self with the functions of the body-mind complex, and we also confuse ourselves with the contents of those functions. This confusion, like the others, results in suffering.

“Don’t you see that all your problems are your body’s problems - food, clothing, shelter, family, friends, name, fame, security, survival - all these lose their meaning the moment you realise that You are not a mere body.”

- Nisargadatta Maharaj

Now, while these two aspects are problematic in themselves, there is a third aspect of this same confusion, which runs deeper. This third aspect is fundamental to the other two, and to all the confusions we have discussed so far.

Aspect #3: Veiling and Projection (aka ajnaana)

After defeating the Minotaur and returning from his travels, Theseus finally returned home. Upon his return, he was celebrated as a hero, and as a monument to his glory, the people decided to put his ship up in the city center, with a plaque that read “The Ship of Theseus.”

Years went by, and one day, a visitor noticed that one of the planks had started to rot. They alerted the keepers of the monument, who promptly had the rotten plank replaced with a new one.

A few years later, another visitor noticed that a plank of wood was rotten, and so once again, it was replaced.

This happened over and over again over a period of several decades until eventually, about a hundred years later, not one original plank of wood remained.

Is it still the Ship of Theseus?

P: Yes, of course it is.

Jogi: Ok, now imagine that all the old planks were kept safely, and put together in a large warehouse some distance from the monument. Now which one of the two is the “real” ship of Theseus? The monument in the city center, or the ship in the warehouse?

P: I see, so then I guess the monument is not the ship of Theseus.

Jogi: Ok, when did it stop being the ship of Theseus? Was it when the last plank was removed?

P: No, some time before that.

Jogi: Was it when the first plank was replaced?

P: No, some time after that.

Jogi: So where do you draw the line?

P: Probably when more than half the planks were changed out?

The key here is not what boundary was decided upon, but rather that Jogi and P had to collectively agree on a boundary. This collective agreement is not actually “out there”, but is a projection of thought - a mental construct (specifically, a vikalp). The boundaries that define any object are not “out there”, but rather are in the mind of the perceiver. That is, what we call “objects” are not actually real in themselves - rather, they are a projection of thought onto boundary-less nature for the sake of convenience and communication.

“[You cannot] cut a cheese with a line of longitude.”

- Alan Watts

Why do we care about this hypothetical example?

This is how we treat our bodies, our minds, and all the objects around us. Objects are defined by their boundaries, but these boundaries are nothing more than a symbol, created by collective agreement.

We agree upon these boundaries through conditioning, socialisation, and education, but in reality there are no actual objects out there. Sure, there are clusters of individual, momentary perceptions that are in constant flux, but what we call “objects” are not real in themselves. They are mental projections. We group these momentary, shifting, individual perceptions and give them names, then sort of “forget”2 that we did that, and finally take the conventional groupings seriously.

Once we take the groupings seriously, we then act as though the objects have some sort of “essence” hiding within, when really, that is a convenient fiction.3

This especially becomes a problem when we apply this confusion to ourselves and start to selectively identify with some of these clusters of perceptions.

To make this clear, consider the body. What we call “the body” is in fact just a cluster of perceptions, constantly shifting around. I ate rice yesterday, and now that rice is me. Later, I go to the bathroom, and what left my body is no longer “me.” At what point did it start being me? At what point did it stop being me? Where is the boundary between “me” and “not me”?

“Problems that remain persistently insoluble should always be suspected as questions asked in the wrong way”

- Alan Watts

These questions only seem difficult or “philosophical” because of a deeper confusion. The boundary itself is made up. There is no physical boundary between self and non-self - there never was - it was only ever a mental creation. Reality has no boundaries. To use a classical example, asking a question about the boundary between self and other makes as much sense as asking a question about the horns of a rabbit. Rabbits don’t have horns, and so any question about the horns does not make sense.

Like with the other confusions, we build up a wall to avoid facing this truth head on. Often, this looks like discussion of a “soul” or an “essence” hidden somewhere within. Even when reading about the Purusha, the mind may jump to an image of some sort of luminous orb floating in the center of the heart or in the head, or perhaps a translucent, glowing humanoid within the body. These are just images, and are not what is being referred to as “Self.”

The Self is not an object, it is the power of Awareness with which you are seeing this phone or laptop screen, with which you are listening to the inner voice reading these words, which is in all of your experiences, that witnesses all change. That Self has no colour, no form, no shape, no division, for all colour, form, shape, and division appear within It.

“As an unintelligent man seeks for the abode of music in the body of the lute, a conch-shell, or a drum, so does he look for a soul within the skandhas (ie. the body-mind complex)”

- Lankavatara Sutra, Sangathaka 757

Now what?

Yoga follows the format of ancient Indian medicine, wherein first there is a diagnosis of the disease, then the cause of the disease is found (the etiology), followed by the prognosis, and finally the course of treatment.

Here, the diagnosis is dukkha - the constant sense of unease and the cycle of suffering. The cause of dukkha is avidya, the primal Ignorance, that manifests in the four confusions. The prognosis, if the course of treatment is followed, is Moksha (ultimate freedom), and the course of treatment is Jnana, or Knowledge of the Self (also known as Samyak-Darshana or “correct-seeing”). In Raja Yoga, the method to attain Jnana and thus get rid of avidya is the eight-limbed Yoga.

Starting next week, we will go through an overview of all the eight limbs, followed by a deep dive into each of them, along with practices that you can cultivate in your life to systematically remove avidya, while getting the benefits of the side effects (ie. a calm mind, etc.) along the way.

Yoga is not just philosophy - it is a set of real-world practices that anyone can benefit from, as long as you have a mind, and a willingness to put your thoughts into action.

Until next time:

Continue your practice of Kriya Yoga. This will help you to build up the willpower to actually turn these ideas into action, rather than leaving them as ideas that you read in an article once upon a time. If you are finding your Kriya Yoga to be too difficult, cultivate eka-tattva-abhyaas (focusing on one thing at a time), and the four attitudes (friendliness, compassion, gladness and equanimity) in the appropriate situations using your daily life as an opportunity to practice.

Notice where you are hiding from the truth of suffering - closely observe what you call “pleasure” to find the threefold dukkha hiding within.

Notice times where you use language (mentally or verbally) to confuse self and non-self. Language is the expression of your tendencies, and these expressions in turn leave strong impressions on the mind (thus creating more tendencies, or strengthening existing ones). Instead of thinking “I am sad” or “I am happy”, reframe the thought to “I notice sadness in the mind” or “I notice happiness in the mind.” Similarly with the body, reframe “I am thin, tall, fat, etc.” as “The body is thin, tall, fat, etc.”

Next time: The Eight-Limbs of Yoga: Uncovering the Self

The term “threefold suffering” is also used to describe the three sources of suffering - adhyaatmika (suffering caused by oneself), adhibhautika (suffering caused by other living beings), and adhidaivika (suffering caused by the elements, such as natural disasters). Incidentally, this usage of the term “threefold suffering” is the reason that there are three repetitions of the word “shaanti” (ie. peace) in the chant “Om Shaanti Shaanti Shaantih.”

The technical term for the “forgetting” is aavarana shakti or “veiling power,” The technical term for when the clusters of perceptions are grouped, given names, and taken seriously as “real” is vikshepa shakti or “projecting power.” These are the two powers of Maya.

Up until this point, this grouping of momentary perceptions for the purposes of communication, measurement, and transaction is called ajnana (pronounced uh-gyaah-nuh). At the Universal scale, ajnana is called Maya, and it creates the illusion of the manifold Universe. When ajnana is applied to the body and mind, creating the illusion of a separate individual called “me”, it is called avidya.