Q&A: Why is it necessary to understand the types of suffering?

Understanding over faith to build intrinsic motivation, and the place of morality in Yoga

Note: These next few articles will be devoted to answering questions asked by readers. If you have questions, please submit them by clicking the button below.Why is it necessary to understand the types of suffering, if the solution we are arriving at is that any action taken to alleviate that suffering is Yoga? Why not focus on the modes of alleviation? And where does morality fall into "any action"? What if an action hurts another?

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Thank you for your question 🙏🏽

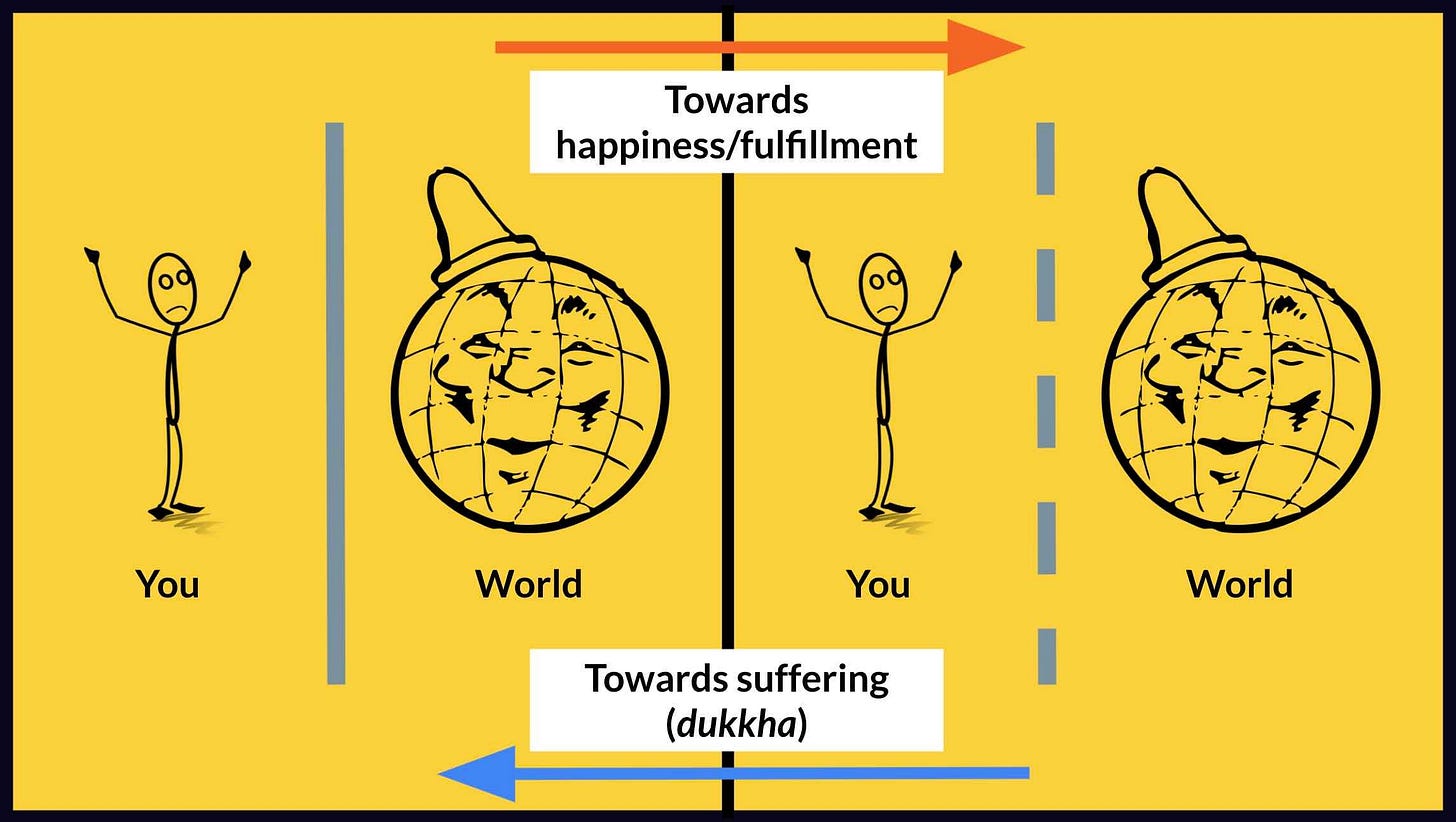

Normally, we think that certain actions lead to happiness, while other actions lead to suffering.

For example, we may feel that if we make money it will give us happiness, or if we lose money we will feel pain. We may feel that if others like us it will give us happiness, but if we do something such that others look down upon us it will lead to suffering.

In one sense, this is correct.

We directly experience that every action has consequences, and we classify some consequences are “positive”, and others as “negative”.

These positive outcomes give us a sense of happiness, known, in Yoga, as hlaad.

The negative outcomes result in a sense of pain, known as paritaap.

ते ह्लादपरितापफलाः पुण्यापुण्यहेतुत्वात्।Te hlaadaParitaapaPhalaah punyaApunyaHetutvaatThese [the results of karma, ie. birth, life span, and life experience] are experienced as pleasure or pain, and are the fruits of of merit and demerit.

- Yoga Sutra, 2.14

However, if we look closely, we will notice that even those outcomes which we would normally consider to be pleasurable or positive are limited, temporary, and unsustainable.

In fact, even the most pleasururable experiences are just dukkha in disguise.

One example we have used in this series is that of a vacation.

Imagine you are going on a vacation for a few weeks. You look forward to the vacation before it happens. Then, while it happens, you enjoy it. Finally, once it is over, you look back upon it with a sense of nostalgia.

If we investigate closely, however, we will find that these positive feelings are shrouded in suffering.

Before we go on the vacation, we long for it to begin. The mind is scattered, and the present moment begins to feel dull in comparison. This is dukkha.

Then, while we are on the vacation - either it exceeds our expectations, or it is below our expectations. If it is below our expectations, we suffer, especially if we had placed a lot of emotional weight while we were longing for it. On the other hand, if it is above our expectations, we still suffer out of longing for it to not come to an end.

Finally, once the vacation is over, we suffer because it is now over, and we long to repeat the experience at a future time.

To summarize, we suffer before, during, and after the pleasurable experience. We certainly experience the pleasure of it - however, it is shrouded in suffering.

For more on this topic, you can take a look at the article here:

In this way, we see that our normal thought process, where we distinguish between pleasurable and painful experiences - between happiness and suffering - is erroneous.

Our base assumption of this bifurcation was incorrect the whole time. This is why it is said that the one with discernment sees suffering in all experiences.

दुःखं एव सर्वं विवेकिनः।Dukkham eva sarvam vivekinahTo the one with vivek (ie. discrimination), everything is indeed suffering.

- Yoga Sutra, 2.15

Normally, we do not stop to think about this fact.

As a result, we continue on with our lives looking for fulfilment by maximizing hlaad and minimizing paritaap. We continue to be disappointed, but rather than investigating why we don’t achieve ultimate fulfilment in this way, we somehow feel - whether consciously or not - as though the next time will result in greater happiness.

As a result of this, we end up spinning on the hamster wheel of samsaara, blindly producing suffering for ourselves.

P: Why is this bad?

It is not bad. It is just the consequence.

If we want to continue spinning on the wheel of samsaara, great. The only problem is that we will continue to experience dukkha, and will not know why. The truth hits whether not we know about it - just like gravity will drop a person to the ground whether or not they know any physics.

Yoga starts with an investigation into the diagnosis so that we can see that our current course of action doesn’t work. By investigating dukkha, we see that our normal course of action - running after hlaad and running away from paritaap - is not actually moving us away from dukkha.

P: But why do we need to see that our normal course of action isn’t working? Can’t we just start practicing the techniques of Yoga? Why not just focus on the modes of alleviation?

Both are true. The Yogi must understand the cause and focus on the modes of alleviation.

If we just understand the cause and don’t focus on the modes of alleviation, this knowledge will be utterly useless - like a person who knows that they have a disease and yet do not take any medicine.

On the other hand, focusing on the techniques in isolation without knowing why we are doing so will result in a short-lived and shallow practice.

P: How?

We certainly can focus on the modes of alleviation in isolation, and start to practice the techniques of Yoga without understanding the root problem. However, what would be the motivation to do so?

As we have seen, Yoga takes immense effort - known as veerya, or vigour. Without intrinsic motivation, any vigour is likely to be short-lived.

We are creatures of habit, and have formed a deep habit pattern of following hlaad and running away from paritaap - a habit of spinning on the hamster wheel of chasing momentary happiness and running away from pain. Without intrinsic motivation, the Yogi is highly likely to fall back into this comfortable pattern, rather than shifting it to break out of the hamster wheel.

But let’s say there is motivation. What could it be grounded in?

Most likely1 it would be grounded the authority of the texts, or of a teacher. Maybe the Yogi has heard that Yoga will help them, and so they do it. But this is blind faith - they do it because they think it is somehow good, without understanding the reason behind it.

P: What’s wrong with this?

Blind faith is the antithesis of Yoga.

Yoga is an unwavering search for the Ultimate Truth. Blind faith blocks us from uncovering the truth.

P: Why?

Because it leads to attachment.

Here, the attachment is to an idea, method, text, or teacher. Attachment is raag - a klesha - that clouds the mind from seeing the truth, and ultimately shrouds liberation. Ultimately, all attachment - even to the idea, method, etc. - must be ultimately given up.

If the Yogi understands the root problem - dukkha - and how it affects them, only then can they give up the method without fear. Otherwise, they will cling to it, and as a result not progress beyond a certain point.

Belief is, ultimately, a doubt. We only believe in what we don’t know.

You can read more on this topic here:

“And is not this acceptance of a belief, the covering up of that fear - the fear of being really nothing, of being empty?

After all, a cup is useful only when it is empty; and a mind that is filled with beliefs, with dogmas, with assertions, with quotations, is really an uncreative mind, it is merely a repetitive mind.”

- Jiddu Krishnamurti

Additionally, even if the practitioner begins with the motivation of blind faith, eventually the mind will clear up sufficiently that they will start asking questions.

Why should I keep doing this? I am going to spend my life on this, what is the purpose?

If the motivation is blind faith, these questions will come up without an answer, and the person will lose motivation, and so stop practising, or practice without vigour. On the other hand, if the motivation is through an understanding of the root problem, the person will have answers to these questions and so have good reason to continue their practice.

Next, Yoga requires the Yogi to be able to experiment with which techniques work for them, which ones don’t, to investigate the reasons why, and then adjust their practice accordingly. If the Yogi does not know the underlying problem they are working to solve, they will not be able to adjust their practice without external help.

This is like someone who is trying to reach a destination with some directions but does not know what their destination is. When they hit a roadblock, or if they don’t see the landmark that they were expecting to see, they will be completely lost and unable to progress.

Furthermore, practice in Yoga - abhyaas - is discussed as follows:

स तु दीर्घकालनैरन्तर्यस्त्कारासेवितो दृढभूमिः।Sa tu deerghaKaalaNairantaryaSatkaaraAsevito dridhbhoomih[Practice] becomes firmly established [when it is done for] a prolonged period of time, without interruption, with internal honesty/sincerity, and with careful attention.

- Yoga Sutra, 1.14

The second factor of practice on this list - nairantarya (without interruption/incessantly) - means that the Yogi is literally practising all the time, without a break.

This means that every moment of the Yogi’s life is transformed into Yoga.

Even when they are not sitting in meditation, in every task, they focus on one thing at a time - eka-tattva-abhyaas. Their personal conduct is the Niyamas, and their external relationships are the Yamas. Difficult social situations become a field to practice the Brahmavihaaras, and their work becomes Ishvarpranidhaan (aka Karma Yoga).

All of this follows automatically once the Yogi is intrinsically motivated.

If the motivation is extrinsic (e.g. a teacher, a community, etc.), this becomes very difficult. After all, it is not practical for someone else to have to constantly monitor a person’s thought patterns throughout the day - this is most effectively done by the practitioner themselves.

P: Ok, I get it. A Yogi needs intrinsic motivation in order to practice nairantarya - incessantly. But why do they need to practice incessantly in the first place?

This is a good question. In Yoga there is no compulsion. Every “should” must be followed by a “so that.”

If the Yogi does not practice incessantly, then progress will be slower. If the Yogi practices following the four keys, then progress will be faster. Even a little practice is helpful. However, given the reasons above, we can see that an intrinsically motivated Yogi will make quicker progress than an extrinsically motivated one.

There is more discussion on this topic at the article below:

P: Is any action taken to alleviate suffering considered Yoga? What about actions that harm another person?

No. Not all actions are Yoga.

For example, a person may act selfishly out of greed, and harm another to gain what they want. This is not Yoga.

A person may lie to someone in order to protect their self-interest. This is not Yoga.

Yoga is specifically that set of actions and knowledge that help us to break free from the hamster wheel - the duality of hlaad and paritaap - which allows us to break free from dukkha and the cycle of samsaara.

Yoga is specifically that set of actions and knowledge which can help us to remove avidya, and so become free.

P: Where does morality fall into all of this?

It depends on what is meant by “morality.”

One one hand, there is dharma - “doing the right thing.” Yoga does not explicitly deal with dharma. Texts on Yoga are moksha-shaastras - teachings dealing with liberation and freedom from dukkha. There is, however, an entire body of (non-Yoga) texts known as dharma-shaastras, which exclusively deal with various actions which are considered moral and ethical.2

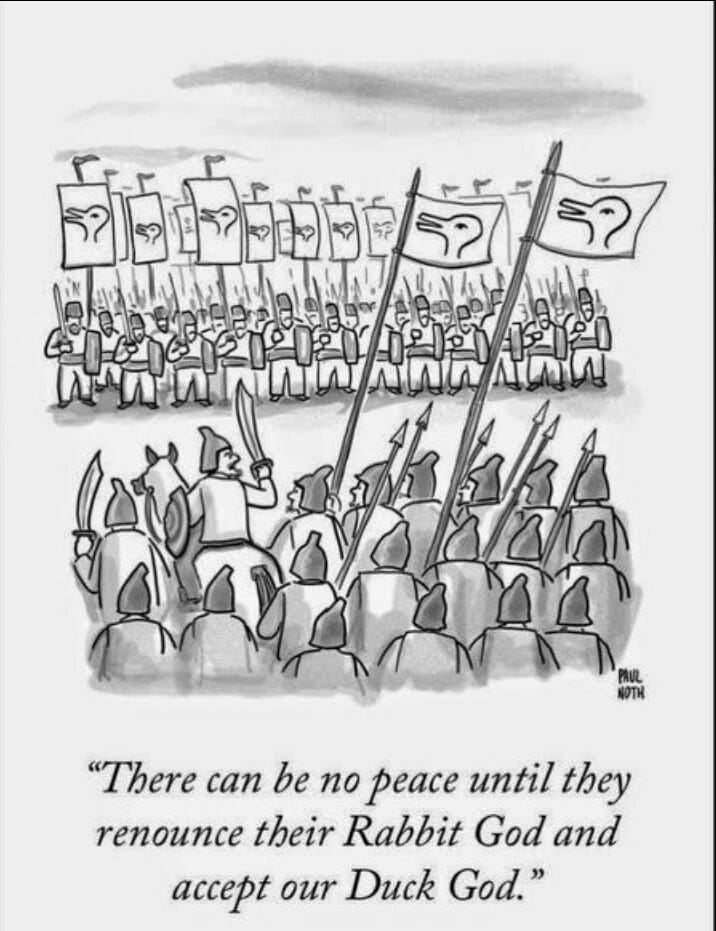

From a Yogic perspective, upon some investigation, we see that morality and immorality are relative to each other. This means that one cannot exist without the other - like “up” and “down”, or “left” and “right”. Additionally, the boundary between “moral” and “immoral” changes from time to time, place to place, and mind to mind. Given this, we see that there can be no such thing as absolute morality, unless, of course, it is rooted in belief. But belief is simply a tightly held concept, and this is, as we have seen above, counterproductive to the goal of Yoga.

P: Ok, I get it. There is no universal morality, and any tightly held belief is counterproductive to Yoga. But even so, does morality have any place in Yoga?

The Yamas are the closest thing to a moral system within Yoga.

As a reminder, they are:

Ahimsa: Non-violence

Satya: Truthfulness

Asteya: Non-stealing

Brahmacharya: Non-indulgence

Aparigraha: Non-ownership

Of these ahimsa - non-violence - comes first, and is prioritized above all else. For example, it is in line with the Yamas to tell a lie to avoid harming another, but it is against the Yamas to harm another to avoid telling a lie.

In a sense, the only Yama is ahimsa, and all the others are just methods of teaching ahimsa to show the subtle extents of what can be meant by “violence” in a Yogic context.

On the surface, the Yamas look a lot like a moral system, but they are not. Rather, they are a method to break down avidya - specifically the barrier, in thought, between what we normally consider “self” and what we normally consider “other.”

In this sense, anything which goes against the Yamas can easily be discarded as “not Yoga.”

With regard to the matter of belief above, we may note that belief - including belief in a system of morality - is, in itself, a form of violence. By holding on to a particular set of beliefs and considering them to be ultimately correct, the practitioner - perhaps unknowingly - separates “self” and “other”, and so violates the Yama of ahimsa.

The Yamas are the first limb of Yoga, and are prioritized above all the other limbs.

That is, a person may meditate, pray, or study incessantly, but if they violate the Yamas, does not achieve the desired outcome, since the boundary between “self” and “other” will remain strong, or even become stronger.

The purpose of Yoga is the dissolution of this very boundary, and so the Yamas are a critical piece of the foundation.

For more discussion on this topic, take a look at the articles starting here:

TL;DR

To summarize, understanding dukkha helps to build intrinsic motivation in the Yogi, and this intrinsic motivation is necessary to expedite progress and keep the Yogi on the path.

Without understanding the root problem of dukkha, it is difficult to build intrinsic motivation, and without intrinsic motivation, it is easy to fall off the path, and difficult to maintain a continuous practice. Furthermore, without knowledge of the root problem, it is impossible to adjust one’s practice through direct experience, the moment it deviates from the teaching. And since all teachings are words, and all words are abstractions, there cannot be any teaching that perfectly captures all the possible intricacies of all possible minds at all possible times.

While all actions are done - knowingly or unknowingly - for the same reason (ie. the pursuit of fulfilment and avoidance of dukkha), most of our actions simply keep us on the hamster wheel of samsaara by leading to momentary pleasure and pain, resulting in further action, ad infinitum. In this way, not all actions are Yoga.

Yoga is specifically that subset of actions which helps the practitioner to break out of this hamster wheel, and is defined as chittaVrittiNirodha - the cessation of the whirlpools in the mind.

Finally, the place of morality in Yoga is that Yoga is not actually about morality at all. This is similar to asking what Yoga has to say about computer science, building bridges, or environmental regulations. While one may apply a Yogic mindset of truth-seeking to these subjects, Yoga is not actually about these things. Rather, Yoga’s sole focus is the cessation of dukkha, and methods to Realize the Self. Having said this, the Yamas - the first limb of Yoga - closely resemble a moral system.

However, they are, in actuality, a method to weaken the boundary between “self” and “other”, not moral injunctions of what one “should” or “should not” do.

This is summarized beautifully by the great Ramana Maharishi. When asked by a questioner “how are we to treat others”, he responded:

“There are no others.”

- Ramana Maharishi

Once again, thank you for your question. I hope this helped to answer it.

If there are any lingering doubts, or additional questions that stem from this response, please do not hesitate to reach out. You can reach out by directly responding to this email, by clicking the button below, by commenting on the post, or by posting anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup.

There are examples in the smritis of Yogis who attained liberation motivated not by knowledge, but by anger, fear, or delusion, such as Dhruva who was motivated by anger with his father, Uttaanapaada, or Kamsa, who fixed his mind undeviatingly upon Krishna out of hatred.

The four best-known “Dharma Shaastras” are the Manusmriti, the Yajnavalkya Smriti, the Naradasmriti, and the Vishnusmriti. Reading these texts makes it clear how what is considered “moral” in one place and time can be considered highly immoral in another place and time. In this way, holding strictly and without question to a set of moral principles can lead to violence, and has done so throughout human history.