How sticky is your mind?

How meditation leads to happiness and resilience

If you are new to this newsletter, welcome, and thank you for joining us on the journey!

Yoga - like this newsletter - builds upon itself, and so in order to make the most of these teachings, I would strongly suggest starting at the beginning, here, and making your way through by clicking on the link at the bottom of each article to get to the next one:

Alternatively, if this is too much, you can try clicking on the links in green (like this) to open previous articles (or sections of articles) that are relevant to the current topic.

Finally, you can always (I mean always) reach out directly with feedback, questions, or comments by leaving a comment down below, responding directly to this email, or posting anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup.

🙏🏽❤️

Kunal

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

“The source of joy is not in the external world of objects, but is deep within us, and when the mind is at perfect rest, effulgent beams of the inner Bliss pour out its satisfying joy.”

- Swami Chinmayananda

Over the past several weeks, we have been discussing meditation, or Dhyaan - the seventh limb of the eight-limbed Yoga. The word “meditation” has come to mean many different things, often including things like general mindfulness, cultivation of attitudes like metta or compassion, breathing techniques, observation of thoughts, prayer, and contemplation.

In Yoga, however, meditation - called “Dhyaan” - has a very clear definition:

तत्र प्रत्ययैकतानता ध्यानम्॥Tatra pratyayaEkataanataa dhyaanamThere [ie. in Dhaaranaa], Dhyaan is when [attention is continuously] fixed on the same pratyaya.

- Yoga Sutra, 3.2

At first, the mind is brought to focus on an object. When it wanders, the attention is returned to the object, called the aalambanaa, or support. This is called Dhaaranaa, or concentration - the sixth limb.

Eventually, the mind effortlessly “sticks” to the aalambanaa - this could be the breath, a mantra, an image, or any other object. This state is known as Dhyaan, or meditation.

We have previously discussed the two main functions of Dhyaan:

To weaken the kleshas from a tanu (weak) to prasupta (dormant) state.

As a stepping stone to Samaadhi, or absorption

We then began a discussion on the side effects of meditation. In particular:

Increased focus

Increased happiness

Increased resilience

Last week, we discussed the first of these - focus. In today’s article, we will go over the next two - happiness and resilience.

Happiness

We have previously discussed how happiness works in the mind. Briefly, the nature of the Self is Bliss1, and all happiness and pleasure that we experience in life is a small reflection of this Bliss in the mind.

Normally, the mind is clouded, like a cloudy sky.

Every now and then, when we fulfil a desire, it is as if one of the clouds temporarily disappears, allowing a ray of light to shine through. However, since happiness from objects (aka vishay-aanand) is temporary, the cloud eventually returns to hide the light once again, until the next time we fulfil a desire. This cycle of happiness and unhappiness continues ad infinitum.

We initially went over this theory of happiness when discussing santosh, or contentment, the second Niyama. Through contentment, the Yogi can reduce the number of clouds, therefore allowing more light to shine through. In this way, practising contentment increases feelings of happiness in the mind.

However, in this analogy, desire is only one of several types of cloud.

As a matter of experience, all mental movements - not just desire - obscure the light of Bliss from shining through. Happiness comes from mental clarity, and is obscured by mental agitation. The more vrittis (mental whirlpools), the less happiness. The fewer vrittis, the more happiness.

One can even extend this analogy to include kleshas. Compare a dark raincloud to a wispy white cloud. A dark raincloud obscures light more than the white cloud.

In the same way, klishta-vrittis obscure happiness more than aklishta-vrittis, and so weakening or reducing kleshas also increases happiness in the mind.

Now consider a concentrated mind.

If attention is entirely concentrated on a singular vritti, it is like reducing the clouds in the sky to a single cloud. This allows for more space for light to shine through, thus creating a feeling of bliss that permeates the mind.

We can notice this phenomenon outside of meditation as well. Any time we are focused intensely on something, to the exclusion of all thoughts, a feeling of peace and clarity permeates the mind. This conclusion is not limited to Yoga psychology. Recent research has also found that mind wandering is generally the cause, and not the consequence, of unhappiness.

A word of caution

This happiness experienced in meditation can be extremely satisfying, and can lead the Yogi to feel like they have arrived. However, note that it is temporary, and only really lasts as long as the mind remains this focused. The ultimate goal of Yoga is the complete cessation of suffering, known as Moksha, or freedom. This is “achieved”2 by the regular practice of Dhyaan, clearing of all kleshas through Samaadhi, and ultimately by removing avidya - the root cause of suffering.

Resilience

"There are these three types of individuals to be found existing in the world. Which three? An individual like an inscription in rock, an individual like an inscription in soil, and an individual like an inscription in water.

"And how is an individual like an inscription in rock? There is the case where a certain individual is often angered, and his anger stays with him a long time. Just as an inscription in rock is not quickly effaced by wind or water and lasts a long time, in the same way a certain individual is often angered, and his anger stays with him a long time. This is called an individual like an inscription in rock.

"And how is an individual like an inscription in soil? There is the case where a certain individual is often angered, but his anger doesn't stay with him a long time. Just as an inscription in soil is quickly effaced by wind or water and doesn't last a long time, in the same way a certain individual is often angered, but his anger doesn't stay with him a long time. This is called an individual like an inscription in soil.

"And how is an individual like an inscription in water? There is the case where a certain individual — when spoken to roughly, spoken to harshly, spoken to in an unpleasing way — is nevertheless congenial, companionable, & courteous. Just as an inscription in water immediately disappears and doesn't last a long time, in the same way a certain individual — when spoken to roughly, spoken to harshly, spoken to in an unpleasing way — is nevertheless congenial, companionable, & courteous. This is called an individual like an inscription in water.

"These are the three types of individuals to be found existing in the world."

- Gautama Buddha, Anguttara Nikaya, 3.3.3.10, translated from Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

What are the things you tend to remember more than others?

Is it easier to remember things that you enjoyed, disliked, or things that were neutral? Is it easier to remember things that had to do with you, or things that had to do with others? Does it take more effort to bring to mind something that relates to a fear, or something that is not related to a fear? Once it is there, which one lingers in the mind longer?

In Yoga psychology, all mental movements (aka vrittis) can either be coloured or uncoloured. That is, they can be klishta (with kleshas) or aklishta (without kleshas). Klishta vrittis draw our attention more strongly than aklishta vrittis.

In order to make this clear, let us review the five kleshas:

Avidya (the Primal Ignorance): The root cause of all suffering (more here and here)

Asmitaa (“I am”-ness): e.g. when you say “my” coffee, “my” job, “my” phone, etc.

Raag (attraction): e.g. when you feel attracted to a chocolate chip cookie, an idea of yourself, when someone praises you, etc.

Dvesha (aversion): e.g. when you feel averse to brussels sprouts, a dirty toilet, a person you don’t like

Abhinivesha (fear): e.g. when something is ending that you wished would continue, when your identity feels threatened, etc.

For more on the kleshas, take a look at this previous article:

Now consider the last thing you were ruminating about.

Specifically, a rumination is a vritti that lingers in the mind - similar to when a song is stuck in your head. Was it a joyful thought or a painful thought?

If we watch the mind carefully, we will likely notice that the thoughts which tend to be “sticky” are coloured with one or more of the five kleshas. For example, it may be a thought about someone who said something to you that made you feel bad (ie. dvesha and asmitaa), a thought about something that triggers a particular fear in you (e.g. a memory of a past trauma - big or small, coloured with abhinivesha), or worry about the future (ie. a vikalp coloured with asmitaa and dvesha).

This may seem fairly obvious for painful thoughts, but if we are honest with ourselves, we will find that even apparently “happy” thoughts that linger are, in fact, coloured. For example, a memory about a pleasant vacation may be coloured with asmitaa and raag, and may be accompanied by a desire to repeat the experience, as well as a lamentation of its ending.

Any thought that lingers in the mind is most likely coloured with one or more kleshas.

P: Why does this matter?

As we have discussed, kleshas darken the clouds of thought in our mind, blocking, as it were, the Bliss of the Self from shining through. As a result, the more kleshas we have, the worse we feel, and the worse we feel, the more kleshas we have. Therefore, in order to feel happy, the first thing to do is to weaken the kleshas.

However, aside from the side-effect of happiness, fewer kleshas also means more mental resilience.

Here, resilience refers to the ability to bounce back from stressful events or thoughts, or difficult situations, without getting stuck in the weeds of thought. It is the ability to quickly and effortlessly return to a state of mental peace and clarity, no matter how agitated the mind was.

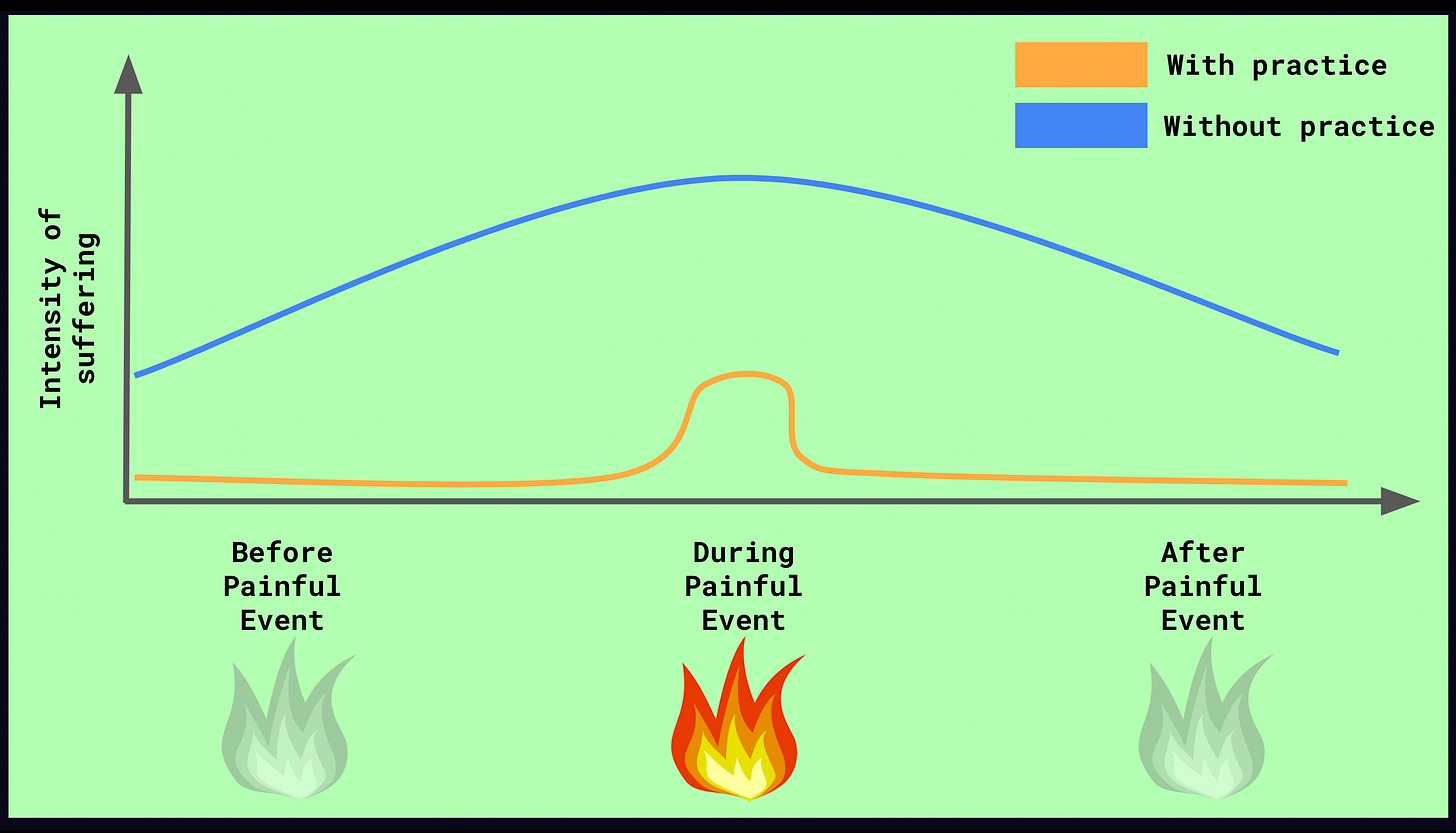

Often, when we face a difficult, painful, or stressful situation, the mind gets lost in thought before, during, and after the actual event.

Beforehand, there is anticipation and trepidation - vikalpa (imagination) coloured with asmitaa, dvesha, and abhinivesha.

During, there is the experience itself - pramaana, in addition to the colourings of asmitaa, dvesha, and abhinivesha, as well as perhaps vikalpas in the form of a desire for it to end, or a fear of it getting worse.

Afterwards, the same kleshas appear over memory (smriti), where we relive the experience over and over again in our heads, in addition to vikalpas in the form of thoughts about how to avoid the situation in the future (ie. asmitaa and dvesha).

As we can see, the kleshas appear in the mind before, during, and after the event, making the mind far more miserable than it needs to be.

On the other hand, if there were no kleshas in the mind, or if the kleshas were weaker, there can be little to no anticipation beforehand, just the unfiltered perception during the experience, and afterwards there can be little to no memory, and nothing but the bare minimum thoughts about avoidance of the situation in the future.

Given the same event, the stronger the kleshas in the perceiving mind, the more suffering is felt, and the longer the suffering is felt for.

The reason for this “lingering” suffering is that klishta-vrittis tend to stick around longer than aklishta-vrittis. The stronger our kleshas are, therefore, the more “sticky” the mind becomes - like inscriptions in rock.

As we weaken the kleshas through meditation, we are likely to find that the mind becomes less and less sticky - thoughts may arise, but they subside just as quickly - like inscriptions in water.

As a result of thoughts becoming more like inscriptions in water, it becomes easier to bounce back from stressful situations, to let go of painful rumination, to change one’s opinion rapidly given new evidence3, and even to rapidly context-switch from one task to another without much loss of energy.

The value of thought in Western-educated society

P: Wait a second. Are you saying that I need to reduce the amount and speed of my thoughts? And are you saying that I should forget everything that happens, and flip-flop on my opinions? How can I function like that?

In Western-educated (aka colonised) society, memory and thought are held in high esteem. We are brought up to value our capacity for holding on to thoughts, and our capacity to maintain a high speed and volume of thoughts. We are trained to feel like holding on to our opinions is a valuable trait - the sign of a “strong backbone.”

However, as we have seen, a high speed, volume, and persistence of thoughts leads to mental suffering, just as a high speed, volume, and persistence of clouds blocks the sun.

This kind of intensity of vrittis and kleshas in the mind leads to feelings of stress, anxiety, and even deep feelings of dejection, sadness, and emptiness. We end up living in a world of thought - mental images - rather than in the fullness of reality before us.

With regard to holding on to thoughts, this also causes suffering in others, as we have seen in so many elections around the world where despite clear evidence, “die-hard” supporters do not change their opinion for no reason except the fact that they once held it.

A Swami once compared the mind of a Yogi to the river Ganga at its source in Gangotri.4 In the winter, it has a minimal volume of water, and is clear enough to see the rocks below. On the other hand, he said, the mind of someone who does not practice is like the Ganga during the rainy season - a high volume of water, and so muddy that you can’t see anything in it.

In addition, he said that while walking through the river during the winter season - when the water is shallow and clear - is difficult due to the cold, you can easily walk through the water. However, in the rainy season - although the water is warmer, and it is easier to step into - one is lucky if they are not swept away by the current when they put even a single foot into it.

In the same way, it is far easier to not practise, and to keep the mind muddy with kleshas and agitated with vrittis. We are educated and bred to do exactly this, and kleshas create the grooves in the mind (aka vyutthaana samskaaraas, or gesticulating tendencies) that encourage it to continue the same pattern of behaviour. On the other hand, while practice takes effort, and can be difficult, it leads to mental calm, clarity, and peace of mind.

P: Ok, I see how it is problematic to have many thoughts, and to hold on to them. But how can I function without the thoughts?

P’s question here hits at the heart of a deep fear we often have of letting go of our thoughts. We may feel that it would be difficult to function in society if we did not think a lot, think fast, and hold on to thoughts.

After all, don’t we need thoughts to function?

The key here is to realise that we need not try to function without thoughts altogether. Thoughts will come, and they are an extremely useful tool. Rather, it is possible to use thoughts without also identifying with them. Additionally, we can learn to let go of unnecessary thoughts, slowly training the mind to generate thoughts only when necessary, and only when desired.

In this respect, thought can be compared to any other function of the body.

We eat in order to survive, and food is an extremely useful tool to keep the body alive. However, if we eat too much, we will become sick. Therefore we learn to eat only when necessary, and only when desired, rather than compulsively.

Similarly, we walk in order to get from one place to another, and walking is an extremely useful tool to get things done. However, if we walk too much, we will injure the body. Therefore, we learn to walk only when necessary, or when desired, rather than compulsively moving around from one place to another until our legs atrophy from exhaustion.

As another example, we speak in order to get a point across to another person, and speaking is an extremely useful tool for the sake of communication. However, if we speak too much, we can injure the throat (and annoy others in the process!). Therefore, we learn to speak only when necessary, or when desired, rather than compulsively making sounds from our mouths.5

In the same way, we can use Dhyaan to learn to use our thoughts as a tool, rather than get lost in the flowing current. We can even learn to gradually reduce and clarify the flow of thoughts, so that it’s not so hard to swim.

With practice, over time, the mind goes from stone, to soil, to water, generating feelings of happiness, focus, clarity, and peace.

Until next time:

Notice the thoughts that tend to linger in the mind more than others. Which kleshas are they coloured with?

If your seated practice is less than 40 minutes per day, increase the length by five minutes.

Take notes to find patterns.

Next time: Sequential practice, how to get to meditation

More on how we know this later. For now, just know that it doesn’t need to be taken on faith. There are thousands of years of rigorous logical argumentation that lead to this conclusion, which we will discuss in a future article.

To say that Moksha is something to be “achieved” is just a figure of speech for the sake of convenience. In Reality, You are already free. You just don’t know it yet.

This is a particularly interesting outcome, because the effect of the klesha of asmitaa is apparent. The stronger the asmitaa (here, pride) colouring one’s “own” thoughts, the harder it is to change opinions when presented with new evidence. Weakening the klesha of asmitaa on the vritti of one’s “own” thoughts makes it easier to change opinions at a moment’s notice, as soon as one has a reason to do so.

Credit for this story goes to the great Swami Sarvapriyananda.

For some of us some of these may be easier than others. However, depending on the tendencies in ones mind, these may also seem difficult to accomplish. This is where Pratyaahaar comes in - the fifth limb of Yoga - to be practised before attempting meditation.