How to be content

The 5 Niyamas: Santosh (Contentment) Part II

Note: Click on the title above to view the full post in your browser.

Ask your questions anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup.

One day, walking along the bank of a river, a rich industrialist came across a fisherman. He was horrified to see the fisherman just lying on the dock beside his boat, smoking his pipe. He asked the fisherman. “Why aren’t you fishing?”

He responded, “Because I’ve caught enough fish for the day.”

“Why don’t you catch more?”

“What will I do with them?”

“You could earn more money, then get a motor fitted onto your boat, then you can go into deeper waters and catch more fish.

“Then you could buy some higher quality nets, and that would allow you to catch more fish and make more money. Over time, you’d have enough money to buy another boat, and eventually a whole fleet of boats. Then you would be rich like me”

The fisherman thought about this for a moment and then asked, “What would I do then?”

The industrialist replied, “What do you mean? Then you could sit back and enjoy life of course.”

The fisherman smiled gently and said, “what do you think I am doing right now?”

For the past few weeks, we have been discussing the Niyamas - the second limb of Yoga. This limb deals with the Yogi’s personal conduct, allowing us to shape our lives in such a way that the centrality of personal conduct (ie. the things we need to do) sort of drops away, allowing the Yogi to move further inwards with ease. The second of the five Niyamas is santosh, or contentment, and is the subject of this week’s article.

Last week, in order to better understand the “why” behind the practice of santosh, we began a discussion on trishnaa (aka the great unquenchable thirst), and vishayaanand.

As a reminder, vishayaanand refers specifically to the type of happiness/satisfaction (aka anand) that we gain from objects (aka vishay).

In particular, we discussed how vishayaanand has three defects, in that it is:

Limited

Temporary

Unsustainable

Most of the time, we don’t stop to consider this fact, even though it is apparent in our everyday experience. Every time we want something, we run after it, both mentally and physically, as if driven by a deep and unquenchable thirst. This thirst is called trishnaa, and is what drives us to act to fulfil our desires. Remember, objects are not limited to physical objects or sense pleasure, but to mental objects like power, goodness, knowledge, ideas, money, or even happiness itself.

Then, when after tremendous suffering, we finally get the object we were after, we are still not satisfied.

Our folly becomes especially apparent at this point when, despite not being satisfied, we somehow fool ourselves into thinking that the next time will be different. In this way, we spend our entire lives in endlessly thirst - in search of a deep and lasting fulfilment that we never truly find.

P: Ok, I get it. Happiness from objects is limited, temporary, and unsustainable. But I still want to be happy. How can I be happy if not by fulfilling my desires?

How happiness works

Analogies are important, in that they inform our mental images which allow us to frame our experiences. Normally, our mental image of happiness and suffering is that of a sine-wave, with crests and troughs representing the so-called “ups and downs” of our mental experience. With this analogy in mind, the idea of contentment seems as though it will be somewhere in between - a sort of dull, perhaps even bland, non-attached evenness of mind.

Rather than this mental image, let us consider a different analogy. Imagine a clear sky with the sun shining above, that is occasionally covered in clouds. Here, the clouds are the kleshas (including desire) in the mind, and the sunlight shining through the gaps is happiness. The more cloudy the sky is, the darker it seems, although the sun is still shining. When there are some gaps in the clouds, streaks of sunlight shine through.

Given this new analogy, consider the example of when you fulfil a desire, any desire at all. In the moment of fulfilment, there is a burst of happiness in the mind.

Now let us ask, how does this happen?

First, when you are chasing a desire, the mind is focused on achieving the goal. This focus is critical.

Then, once the desire is fulfilled, the focused mind becomes momentarily free from thirst. It is this freedom from thirst that we call “satisfaction”, or “happiness.”

As we can see, “happiness” or “satisfaction” is the absence of thirst.

In the analogy, the clouds have been temporarily cleared in one spot, allowing the sunlight to shine through there. In this way, satisfying our desires is one method to gain freedom from a particular desire.

However, as we have seen, this kind of happiness has the three defects of being limited, temporary, and unsustainable.

Additionally, notice that once the desire has been satisfied, the mind is calm for some time as we enjoy the pleasure, but quickly goes back to wandering in search of the next desire, thirsty once again, in an endless game of whack-a-mole.

The reason for this is that the cause of the mind’s focus was the object of desire. The mind was only focused because of how badly you wanted the object. As a result, in the absence of that object (since it has already been acquired), the mind goes back to wandering.

In this way, trying to get happiness by satisfying desires is as futile as trying to blow away all the clouds in the sky. Even with a powerful fan mounted on a giant plane, you may succeed in blowing away a small or medium-sized cloud at best, only to have the wind bring it right back to cover up the sun.

This is summarised in the following traditional story:

Once upon a time, there was a monk who lived with a dog. The dog had a favourite bone that it that it would chew on for some time each day, and then bury in a specific spot in the garden behind the monastery. Every day, the monk would watch the dog going to that spot, digging up the bone, chewing on it, and then burying it right back.

Years went by, and one day the monk began to wonder how the dog was still enjoying its old bone. Reason suggested that it would be old and dry by now, devoid of any juice or flavour. Yet, for some reason the dog kept returning to the same bone, preferring it to other bones offered to it.

Eventually, the monk gave in to his curiosity.

One night, while the dog was asleep, the monk went out to the garden and dug up the bone. As he shone the light of his lamp on the bone, he noticed that it was indeed completely dry, with some sharp edges and splinters. Confused, he buried the bone again, and decided to watch the dog closely the next day.

Sure enough, as the sun rose the next morning, the dog scurried along to the garden, dug up the bone, and began to chew on it. This time, the monk watched the dog closely.

As he watched, he noticed that each time the dog would bite on the bone, a little blood would trickle from its gum on to the bone, and the dog would lap it up. This continued for a while - the dog lapping up its own blood, thinking that it was the flavour of the bone - until the dog had its fill, and returned the bone to its resting place, only to be picked up the next morning.

We are all like the dog in this story.

We run around chasing objects, thinking that they are the source of our happiness, when in fact the happiness already existed within us.1 We keep licking our own blood, thinking that it is the flavour of the bone.

P: But even in this story, the dog needed the bone to enjoy the blood. Don’t we need objects to allow the desire to shine through?

It is at this point that the analogy breaks down. The dog indeed needed the bone to enjoy the blood, but we do not need objects to feel happiness. As we have discussed, using objects to gain happiness (aka vishayaanand) has its defects.

The question, then, is can we can relieve our thirst for objects without using objects?

Here, the analogy of a fire is useful. In order to extinguish a fire, one does not pour fuel. One may pour water, or one may simply let it die out of its own accord.

In this analogy, pouring fuel is like satisfying desires with objects, pouring water is akin to the Knowledge of Brahman (aka completely removing avidya), and letting it die out of its own accord is akin to santosh, or contentment.

How do I practice contentment?

Like the other Niyamas, santosh (ie. contentment) can be practised in two ways:

Practicing santosh as a mahaavrat

“I have learned to seek my happiness by limiting my desires, rather than in attempting to satisfy them.”

- John Stuart Mill

This method of practicing santosh means that the Yogi strives for contentment at all times, in all places, and in all circumstances.

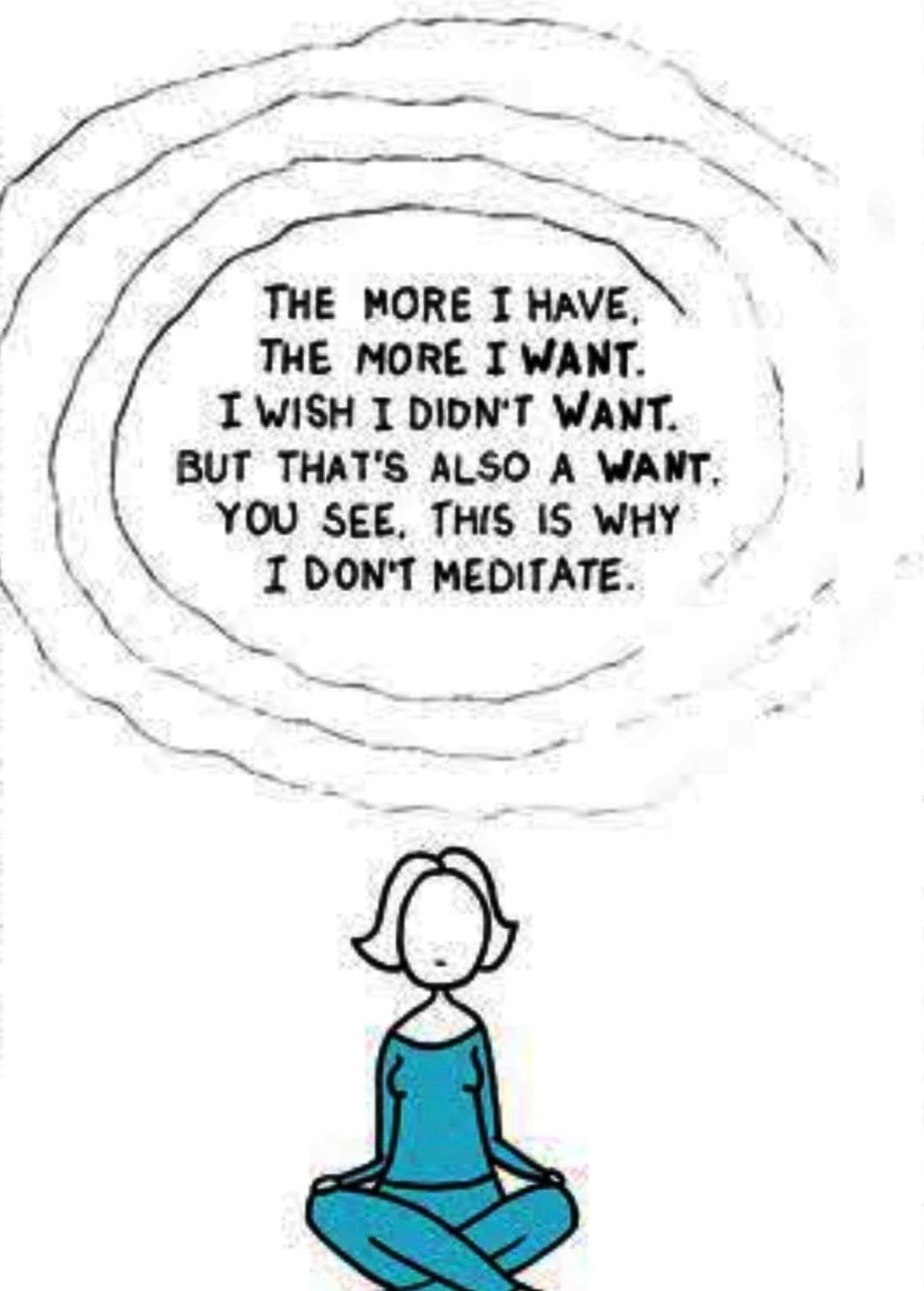

In order to better understand this, consider yourself right now. You are sitting on your phone, laptop, or some other device, listening to these words as the voice in your head reads them to you. While you are focused, there is no room for desire in the mind. However, the moment your attention wavers, gross and subtle thoughts start to crowd the mind - “I need to do the laundry”, or “I need to eat something” or even “I need to be more content.”

Notice these thoughts carefully - especially where they begin with “I need”, “I want” or “I wish.”

Now notice the reaction to them - what is your mental tendency? Are you indulging the thought? Are you stepping on the train and seeing where it takes you? How seriously are you taking the line of thinking? Are you allowing your physical body to be taken in by these thoughts?

Now that you understand the tendency, try to take a step back. Can you watch the train of thought go by and fade back into the depths of the mind, without engaging it? Notice, in simply watching the thought, you are not trying to be content - contentment simply arises.

Practicing in this way during your day to day life is a method of practicing santosh as a mahaavrat (a great vow).

There is more to this as well. We often feel like we need more than we actually do. We feel like we need a big house, a fancy car, fancy clothes, the latest gadgets, and so on, when we are actually confusing a want for a need. What’s more, when we say “need” something, what we ultimately mean is that we feel that without the object, we will not be happy.

This is the root of our confusion. We do not discern between what we need for survival, or for particular consequences, and what we need for happiness. Truly speaking, you do not need anything for happiness - the happiness arises from an absence, or an emptiness, ie. when the mind is free of desire. However, if we indulge this confusion enough, we create tendencies in the mind to treat our wants with the same urgency as we would treat needs, thus resulting in feelings of dissatisfaction (aka dukkha).

Additionally, by constantly rushing to fulfil desires, or even by thinking about what is lacking in the present moment, we create tendencies in the mind that search for what is lacking at all times. As a result, even when all our desires are satisfied, these tendencies take over, and the mind starts to ruminate about how things could have been better. The result of these tendencies is a continuous and pervasive feeling of being unfulfilled and unhappy, no matter how “amazing” your life may look from the outside.

In this way, the tendency to seek for happiness is the cause of our suffering.

The practice of santosh helps to weaken these tendencies. In this case, it looks like stopping for a moment to question the urge as it arises. Ask - is there a need for this object aside from satisfying a klesha? Does it serve any practical purpose? If not, actively remind yourself that - to quote Adi Shankaracharya - “this is enough.”

Wanting more than what we need prevents us from clearly seeing what we already have. It is the very wanting, or thirsting, that is the cause of our unhappiness.

If you are reading this, you are likely blessed with food, safety, shelter, money, education, opportunities, and knowledge, at the very least. Even if not, you are, at the very least, alive and well. Actively practicing gratitude for what you have results in feelings of contentment - realising that you lack for nothing, except in thought.

P: But what about those who are poor? Should they also practice contentment? If happiness is in the mind, why can’t they be happy?

Jogi: First of all, the practice of santosh, like all of Yoga, is a highly personal practice. Everyone has a different situation, and different mental tendencies. If someone does not have money, it is beyond your control whether or not they practice santosh. However, it is within your power to practice compassion. Feed who you can, clothe who you can, help to relieve the suffering of others. Ramakrishna is known to have said that it is a sin to teach a hungry person religion - first give them food, then talk to them of God.

P: Ok, so I should act to relieve the suffering of others. But isn’t that a violation of contentment?

Jogi: Contentment is independent of apparent action or inaction. Contentment lies in your dependence on external events for your own happiness. You need not stake your happiness on whether or not your relieved the suffering of others effectively, or at all. Do your best to relieve suffering, but do it without attachment to the result of the action.

You can only sit in one car at a time, you can only live in one house at a time, and you can only use so much money for all of your practical purposes, but thought tells us otherwise. We feel that we lack, but if you stop for a moment, close your eyes, and take a deep breath, what do you need in this moment? Be honest - do you really need anything right now? Knowing this, and reflecting upon it, we can strive to always want less.

In the Christian tradition as well, Jesus says,

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for they shall see God.”

- Matthew 5:3

Living in this way, making sure that you strive only for what you need, and, crucially, that you do not depend upon objects for your happiness, at all times, in all places, and in all circumstances, is santosh.

To quote Hariharananda, “In order to avoid injury from thorns, one need not cover the entire earth in leather. Rather, one must simply wear a pair of shoes.”

P: How can we practice santosh and still be ambitious?

Jogi: What is your ambition?

P: To make money, gain power, and have a good life for myself and my family.

Jogi: Why do you want that?

P: I need to take care of those around me, it is my responsibility.

Jogi: Good.

P: But I don’t have those things right now, and I need them, so I am unsatisfied.

Jogi: Will you be satisfied once you have those things?

P: Certainly.

Jogi: Are you sure?

P: (pauses) no, more things will probably come up.

Jogi: Exactly. There is no limit to how much we can have, but there is a limit to how much we can enjoy. How many sweets can you eat before you start to feel sick?

P: Ok, I get it. I don’t actually need more than I can use, but should I not get at least what I need?

Jogi: Not at all, get what you need, but know when it’s a “need” and when it is just a “want.” Practicing santosh requires a clear discernment (vivek) between these two.

P: But what if those around me are not satisfied? What if my family wants more than I currently have?

Jogi: Then work to satisfy them, but know that you yourself are already satisfied.

P: But if they’re not happy, then I’m not happy. I can only be satisfied when they are.

Jogi: Are you hungry when they are hungry?

P: No.

Jogi: Then you can be satisfied when they are not satisfied.

P: But I want to feed them when they are hungry.

Jogi: Then feed them, by all means.

P: Now I’m confused.

Jogi: Your feeding them is a selfless act of devotion, or duty - you are feeding them to feed them, not to satisfy yourself. You are giving them what they want to give them what they want, but you are satisfied in what you have. You do not want more for yourself, even though you may want more for them. This is santosh.

Just because something is necessary for survival doesn’t mean it should also bring us happiness. For example. prosperity may be necessary for survival, but it will not bring happiness. It is simply a tool for survival, not a tool for fulfilment. Knowing this, be happy, whether or not your desires are fulfilled.

As you act, know that you are not acting from a place of desire, but rather that the body-mind is functioning and reacting to its environment as a sunflower turns towards the sun, or as the leaves blow in the wind.

Act with sincerity, but do not take success or failure seriously. This way you are not depleted with failure or inflated with success.

Notice, anxiety and worry come from the results of actions, not from actions themselves. The reason we feel worried is because we are emotionally invested in a particular outcome as opposed to another. As a result, giving up attachment to the fruits of actions results in a feeling of contentment regardless of the outcome.

To be clear, santosh does not mean that one should not do anything and just sit back in sloth. To the contrary, santosh is a highly active, sattvic state of contentment with what one has, no matter the situation, clearly differentiating between what we need and what we want but don’t actually need.

No individual can escape action. Even just laying on a couch, lying on a bed, or sitting in meditation is action, often done with the desire for relaxation. This is not santosh. On the other hand, santosh means letting go (vairaagya) of the desire for fruits of action in the midst of activity, no matter how intense it may be.

Practicing santosh as conditioned by time and place

Prior to meditation, as we sit down, we often have numerous thoughts come to mind which pull us back towards the objects of the world. This is not a problem - rather, it is the consequence of the mind’s natural externalising tendency. As we have discussed, the mind can be likened to a field that is tilted in one direction - when we pour water (here, attention), it flows along channels that it knows, in the downward direction.

Practicing santosh before meditation means an active letting go of these thoughts - noticing them, but not engaging them. Over time, they get weaker, and the Yogi can move further inward.

As you sit, it may help to repeat to yourself gently, “I have nowhere to go, and nothing to do.”

It may also help to inform your family members beforehand that you are going to be sitting for meditation, so that you are not disturbed, and so that you do not feel a pull of others’ expectations during meditation.

Further, it may be helpful to set a timer. There are several apps for this purpose (Insight Timer is great, no affiliation). Set an intention when you sit down that no matter the urge to get up, you will sit until the bell rings. Then, as thoughts arise, and the temptation to get up gets stronger, you can safely watch these thoughts come and go without engaging them.

Finally, visualisations can help too. You can imagine a small box on your right hand side. As thoughts of the “things you need to do” arise, simply notice them and visualise yourself placing them in the box, reminding yourself that the thoughts will be right there waiting for you when you need them.

The result of santosh

Like for all the Yamas and Niyamas, there is a companion sutra which describes the result when the Yogi is completely established in santosh.

संतोषाद् अनुत्तम् सुखलाभः।Santoshaad anuttam sukhaLaabhahFrom santosh comes a happiness that cannot be exceeded (ie without limit).

- Yoga Sutras, 2.42

Normally, we run after objects for happiness (remember, objects are not just physical). When we do this, the limitations of the objects limit the amount of happiness that we get. This is much like how the amount of reflected sunlight that we see in a puddle of water is limited by the clarity of the water. The more mud there is in the water, the less sunlight will reflect. The less mud there is, the brighter the reflection will be.

In this analogy, the mud is the kleshas in the mind. The more we satisfy our desires and aversions, the more we strengthen the kleshas, thus leading to more dissatisfaction, and ultimately less happiness. In this way, our happiness from objects is limited by our desires and our ability to sustainably satisfy them. In simple terms, when we want more, we end up wanting more, leading to a cycle of dissatisfaction.

On the other hand, for the Yogi established in santosh, there is no desire in the mind whatsoever. As a result, there is nothing to obscure or limit their happiness. In this way, santosh brings about a happiness that cannot be exceeded.

Different ways to deal with desire

Over the past several weeks, we have discussed three different concepts relating to desire.

We will make an attempt to clarify some of these ideas here:

Brahmacharya: Non-indulgence, the fourth Yama

Aparigraha: Non-possession, the fifth Yama

Santosh: Contentment, the second Niyama

First let us differentiate between brahmacharya (non-indulgence) and santosh (contentment).

While brahmacharya is a desisting from sense pleasures in particular, santosh is an active letting go of wanting more in general. In this way, santosh is one level more internal than brahmacharya.

To make this clear, consider a scenario in which you are hungry, and need to decide what to eat.

You have some food in the fridge at home, but you want something more. Perhaps you had some similar food the day before, or you don’t think it is tasty enough. As a result, instead of eating what you have, you decide to order food.

Let us break down this scenario. First, you felt a sensation (pramaan-vritti) of hunger. Then, you wanted to fulfil it. Third, you had two opposing ideas (vikalp-vrittis) - eat what’s at home or eat something from outside, and the manas (the lower mind) flitted between the two.

Finally, influenced by the intensity of the klesha of raag (ie. the colouring of desire) upon the vikalp-vritti (imagination) of food from the restaurant, the buddhi (the intellect) decided to order food.

Now how might we have applied brahmacharya and santosh in this situation?

In this particular scenario, practicing brahmacharya would involve not indulging the raag-klesha (your desire for something new). In this case, it would mean desisting from ordering food just to satisfy the taste buds.

Practicing santosh, on the other hand, is one level deeper. This would look like actively reminding yourself that the food in your fridge will satisfy the underlying hunger just as much as any other food, and that you do not need more than what is necessary in order to be happy. For the Yogi who practices santosh, food is viewed as medicine to nourish the body, and nothing more.

Note, this does not mean that one should not eat delicious food, only that one need not rely on the excitation of the taste buds in order to be happy. A simple test for this is to ask yourself if you would be happy without the food. If not, practice brahmacharya in order to weaken the tendency.2

While this example relates to food in particular, it applies to all desires.

Now let us differentiate between santosh and aparigraha (non-possession). In order to make this clear, let us consider a scenario in which you are scrolling through the Amazon app on your phone for a new heated blanket.

Let us break down this scenario. First, you noticed a vritti in the mind - either a smriti (memory) or a vikalp (imagination), or a pramaan (perception) of a heated blanket. The vritti is coloured with raag (the colouring of attraction), and so you feel you want it. This results in an urge to fulfil it.

Now the mind knows that opening the Amazon app will result in a satisfaction of the desire for possession of objects, and so you pick up your phone and click on the Amazon icon.

Next, as you scroll you find a few options that oppose each other, and the manas (the lower mind) flits between them. One of these options is not purchasing the heated blanket at all.

Finally, influenced by the intensity of the klesha of raag (ie. the colouring of desire) upon the pramaan-vritti (perception) of one of the options, the buddhi (the intellect) decides to make the purchase.

Now how might we have applied aparigraha and santosh in this situation?

In this particular scenario, practicing aparigraha would involve not indulging the raag-klesha (your desire for possessing the heated blanket) in the first place. In this scenario it would look like not opening the Amazon app despite the thoughts that came to the mind.

As with the example of brahmacharya above, practicing santosh is one level deeper. This would look like actively reminding yourself that you do not need the heated blanket in order to be happy, despite what the mind is telling you. For the Yogi who practices santosh, possessions are a hindrance to happiness due to their being shrouded in the threefold suffering of acquisition, preservation, and destruction.

As you can see, the Yamas are one level external to the Niyamas. While practicing brahmacharya or aparigraha consists of desisting from indulging the kleshas by turning them into actions, santosh is at the level of the mind, actively reminding oneself that one does not need an object to be happy - whether for the purposes of possession or sense-pleasure.

Until next week:

Notice when the mind says “I need”, “I want”, or “I wish.” Watch the thought with curiosity as you let it go. What sensations arise in the body? How does the breath change? Make sure not to hide from the thought - acknowledge it with openness and curiosity.

As you sit for meditation, use one of the techniques mentioned above to let go of all outgoing thoughts, reminding yourself that they will be there for you when you need them.

Keep track of how the practice of santosh affects your mental well-being. Take notes.

As always, please do not hesitate to reach out with questions, comments, objections, or feedback. You can post here in the comments section or anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup.

Next time: “Talk does not cook rice.”: Tapas (self-discipline)

The following question might arise - how can we logically prove that happiness exists with us? We will discuss this in further detail in future articles on Advaita Vedanta when we go over the nature of the Self as Bliss.

In this way, the Yamas help to reinforce the Niyamas and make them easier to practice. Generally speaking, practicing the earlier limbs of Yoga makes it easier to practice the later limbs.

Really loved the quotes from John Stuart Mill and Shankaracharya!

“I have learned to seek my happiness by limiting my desires, rather than in attempting to satisfy them.”

"This is enough."