Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

There was once a King of the water nymphs who ruled his underwater kingdom. The water people were immortal, but they lacked a soul. The water prince had a favourite daughter by the name of Ondine, and all he wished was for her to have a soul. Now the only way to get a soul was to fall in love with a mortal man.

Out of his love, the prince decided to send Ondine to the surface.

Once she got there, the young Ondine was adopted by a kind fisherman and his wife who lived by the water. Ondine lived there for several years as she came of age.

One day, as she was walking around the nearby woods, Ondine met a knight who had lost his way. Upon first glance, they fell in love, and Ondine took him to meet the fisherman and his wife, where the knight asked for her hand in marriage.

They were married for several years, when one day, Ondine discovered that the knight already had a lover. Enraged, she cursed the knight to only be able to breathe consciously.

As the dejected Ondine left for her home in the sea, the knight simply laughed, not knowing that her curse would spell his certain death. Sure enough, within the span of a few breaths, the knight found himself struggling to stay alert enough to breathe.

That night, he found himself trying to stay awake, afraid of what would come if we fell asleep. Eventually, after several sleepless nights, he could no longer keep his eyes open. Filled with despair and regret for his betrayal of Ondine, he lay in his bed, surrendered to his fate, and closed his eyes for the last time.1

Normally, when we think of breathing, we think of two gases - oxygen and carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is often thought of as a waste product, and oxygen as the “good stuff” - the gas that we need for survival.

As it turns out, there is more nuance to this.

First of all, while oxygen is good, too much oxygen can have a damaging effect on the body, reducing lung capacity and slowing down the delivery of oxygen to the rest of the body. Additionally, it can create irritation and dryness in the throat, and cause damage to cell membranes. This phenomenon, called “oxygen toxicity” doesn’t usually happen with breathing, but it can happen with oxygen concentrators or other forms of supplemental oxygen.

Second, and perhaps most surprisingly, carbon dioxide isn’t all bad.

We have chemoreceptors in the body which gauge the amount of carbon dioxide in the bloodstream. When the amount is too high, the body is automatically triggered to take a breath. The mechanism of automatic breathing, upon which our lives depend, is based on the presence of carbon dioxide. Not having this ability is known as Ondine’s curse.2

Normally, when we breathe, oxygen that enters our lungs binds to haemoglobin in the blood. When the blood reaches a particular area of the body, that oxygen is released into the tissues and organs, keeping them alive.

Carbon dioxide is critical to this release process.

Without carbon dioxide, the oxygen sticks to the haemoglobin, and doesn’t end up in the tissues and organs where it is needed.

Additionally, carbon dioxide plays an important role in regulating stress and anxiety.

For example, one of the most effective treatments for “free-floating anxiety” (the most common form of anxiety today) is a prescription of between two and five inhalations of an even mixture of carbon dioxide and oxygen. It has been found that this simple prescription is sufficient to reduce the baseline level of anxiety from “debilitating” to zero.

Research has also shown that ET-CO2 (end-tidal carbon dioxide, ie. the level of carbon dioxide released at the end of an exhalation) is a significant predictor of the severity of emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety. The lower the levels of carbon dioxide, the higher the severity of the disorder.

In summary, our ability to endure higher levels of carbon dioxide is directly related to our ability to endure stressful situations.

Today’s technique, Moorchha, is a method to improve our resilience to high carbon dioxide levels, thus increasing our resilience to situations throughout our lives.

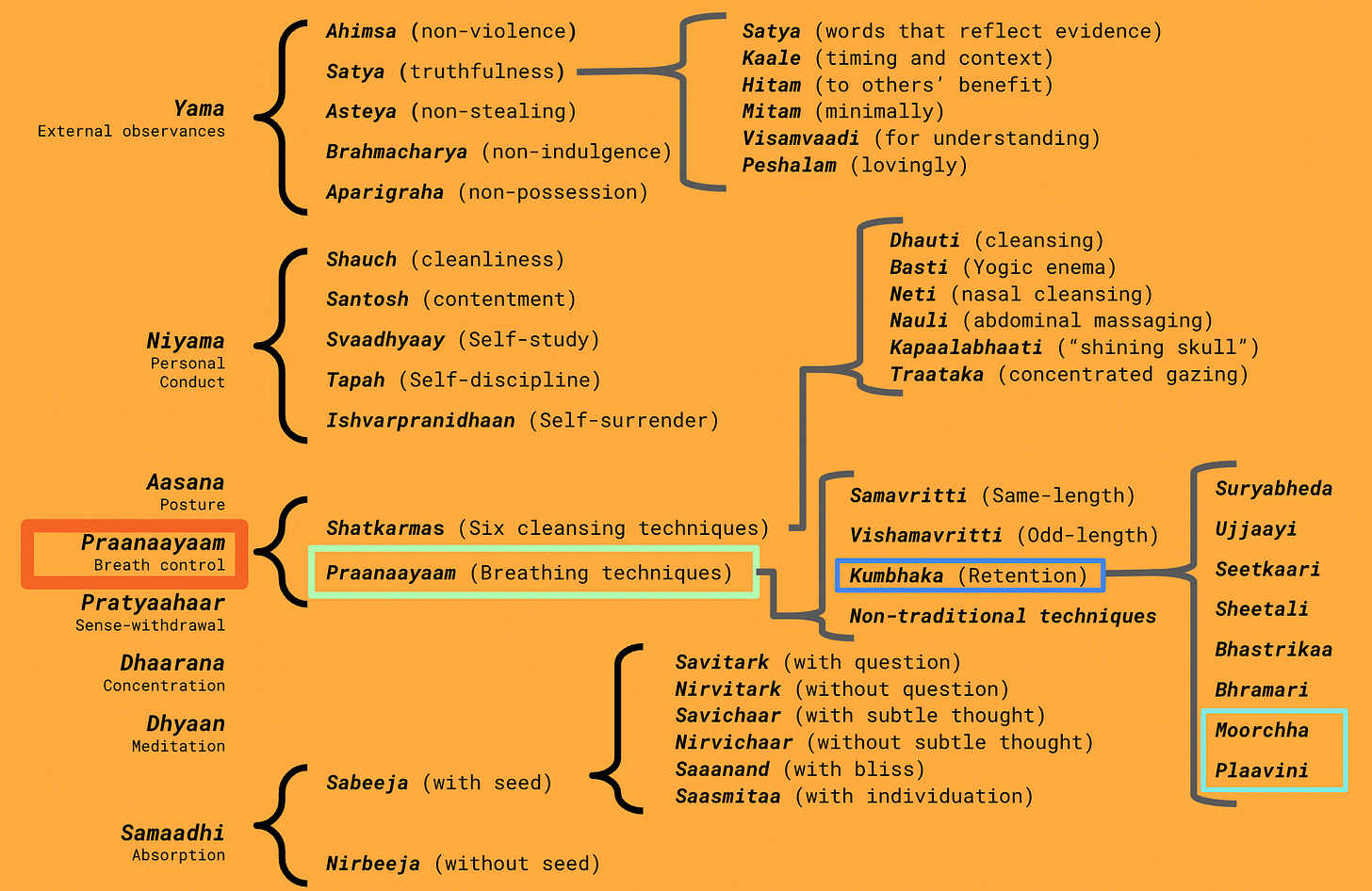

सूर्यभेदनमुज्जायी सीत्कारी शीतली तथा ।भस्त्रिका भ्रामरी मूर्च्छा प्लाविनीत्यष्टकुम्भकाः ॥SooryabhedanamUjjaayee seetkaaree sheetalee tathaaBhastrikaa bhraamaree moorchhaa plaaviniItiAshtaKumbhakaahThe eight Kumbhakas are Suryabheda, Ujjaayi, Seetkaari, Sheetali, Bhastrika, Bhraamari, Moorchhaa, and Plaavini.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 2.44

The eight Kumbhakas are:

Suryabheda: The Secret of the Sun

Ujjaayi: Victorious Breath

Seetkaari: Hissing Breath

Sheetali: Cooling Breath

Bhastrikaa: Bellows Breath

Bhraamari: Bee Breath

Moorchhaa: Swooning Breath

Plaavini: Gulping Breath

Moorchhaa: Swooning breath

पूरकतिं गाढतरं बद्ध्वा जालन्धरं शनैः।रेचयेन्मूर्च्छनाख्येयम् मनोमूर्च्छा सुखप्रदा॥Poorakatim gaadhataram baddhvaa jaalandharam shanaihRechayenMoorchhanaakhyeyam ManoMoorchhaa sukhaPradaaAfter inhaling, slowly fix [the attention] on the jaalandhar bandha. Then, exhale [very] slowly. This is called Moorchha (ie. the swooning or fainting technique) because it makes the mind inactive, and creates a sensation of pleasure.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 2.69

The word “Moorchha” (pronounced moor-ch-haa) literally means “to faint” or “to swoon”, and is named for the effect it has on the practitioner. This is an advanced technique and is meant for practitioners who are able to easily transcend the movements of the mind without getting entangled in them.

To make this clear, consider a time when you were tired. You may say “I am tired.”

While this may seem like a simple statement of fact, if we think about this closely we will notice that in fact, You are not tired. Rather, the mind is tired, and You are observing the tired mind. The problem is that most of the time, in our avidya we are so caught up with the objects of the world that we don’t take the time to notice the facts. As a result, we start to take phrases like “I am tired” seriously, thus identifying with the tiredness, although it is just an object in Awareness.

P: How is this relevant to the technique?

Moorchha Praanaayaam generates a feeling of swooning or fainting. If the Yogi is not absolutely alert, they would simply go into a stupor, increasing tamas, thus hindering their progress. On the other hand, if the Yogi is attentive to the swooning sensation, it can create a clear separation of the Seer from the mind, thus increasing sattva, and helping the practitioner along the path.

P: How does it create a clear separation of the Seer from the mind?

Jogi: Normally, we confuse our mind with Consciousness. This confusion manifests itself when we say things like “I was unconscious”, when what we really mean is that the mind is inactive. By being attentive to the feeling of the mind becoming inactive, we see directly that Consciousness is separate from mind. It becomes apparent that the unconscious, or, more precisely, inactive mind is an object in Consciousness.

P: Ok, I get it. How do I practice?

There are two techniques of Moorchha. For both, make sure to remain absolutely alert and attentive to how the mind moves from the current waking state into the swooning state. This transition must be the object of focus.

Warning: Do not practice this technique if you have been diagnosed with vertigo, high blood-pressure, or heart disease. Additionally, if you start to feel lightheaded, stop the practice and take a few slow, deep breaths using Deergha Shvaasam.

Preparation

Sit in your Aasana, with your head, neck, and torso in alignment, and take a few deep breaths (Deergha Shvaasam) to prepare yourself.

Inhale slowly, deeply, and intentionally through the nose until the lungs are filled with air.

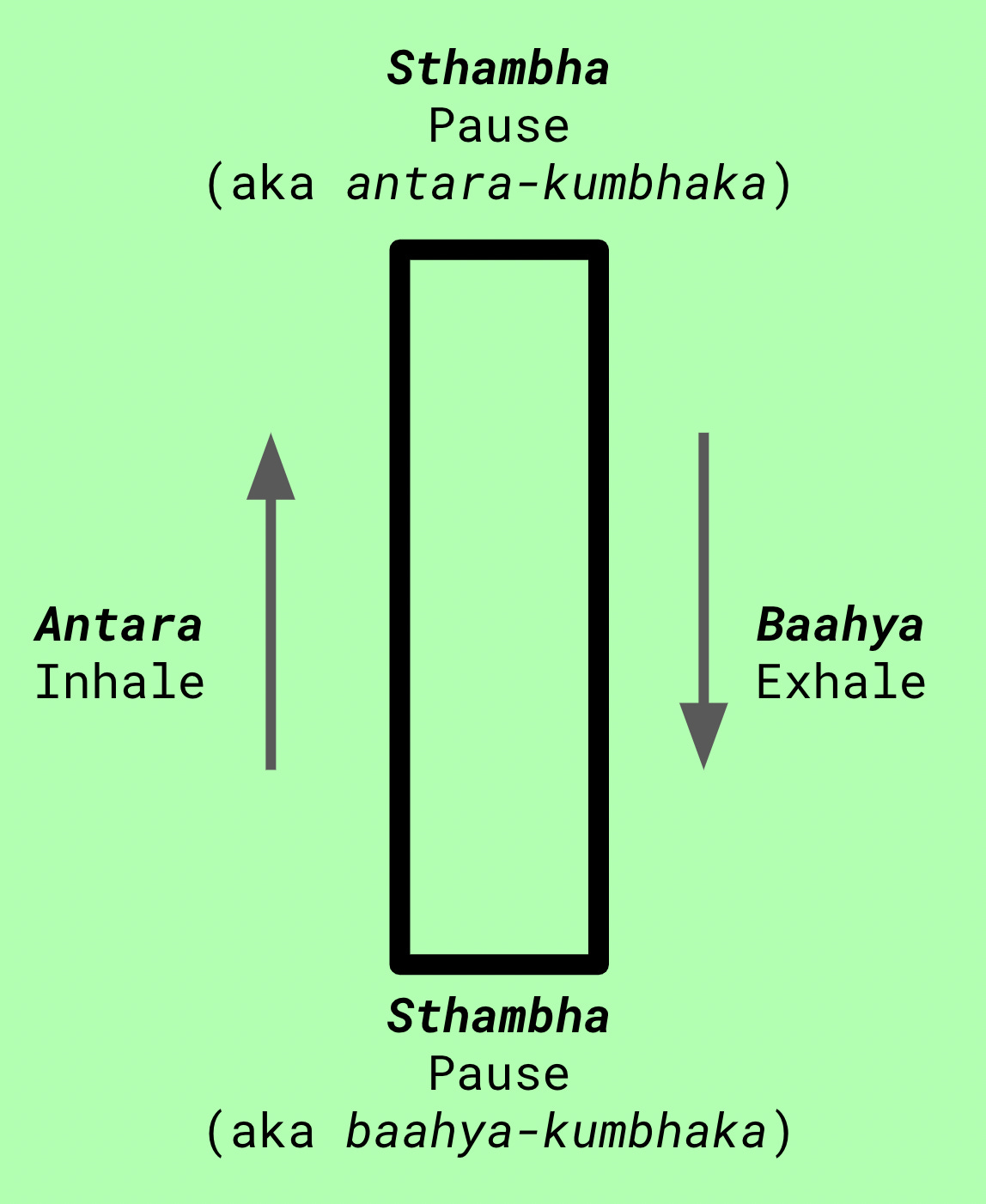

Hold the breath (antara-kumbhaka), lower your head in jaalandhar bandha, keeping the eyes focused on the eyebrow center (ie. shaambhavi mudraa). Count the number of maatraas.

Release jaalandhar bandha by raising the head, lift the chin slightly, and exhale slowly in a controlled fashion until all the air is out of your lungs.

Now, take the number of maatraas, and multiply by 1.5. This will be your hold and exhale time for the technique. For example, if you were able to hold for 20 maatraas and exhale for 40 maatraas, you will now hold for 30 maatraas and exhale for 60 maatraas. Use these numbers for the next sections.

Technique #1:

Sit in your Aasana, with your head, neck, and torso in alignment, and take a few deep breaths (Deergha Shvaasam) to prepare yourself.

Inhale slowly, deeply, and intentionally through the nose until the lungs are filled with air.

Hold the breath (antara-kumbhaka), lower your head in jaalandhar bandha, keeping the eyes focused on the eyebrow center (shaambhavi mudraa). Hold for the number of maatraas as described above (ie. 1.5 the comfortable number from the “preparation” section above)

Release jaalandhar bandha by raising the head, lift the chin slightly.

Exhale slowly in a controlled fashion for the number of maatraas as described above (ie. 1.5 times the number from the “preparation” section), removing all the air from your lungs within the count.

This is one round. Breathe normally for a few minutes before starting the next round, concentrating on the sensation of lightness and emptiness, and the transition of your mind to this state.

Repeat this for three rounds.

Technique #2:

Sit in your Aasana, with your head, neck, and torso in alignment, and take a few deep breaths (Deergha Shvaasam) to prepare yourself. Keep your hands on your knees.

Raise your chin slightly, tilting your head back. If this strains your neck, tilt slightly less until it is comfortable.

Inhale slowly, deeply, and intentionally through the nose until the lungs are filled with air.

Keeping your head tilted back, straighten your elbows, and hold the breath (antara-kumbhaka). Keep the eyes focused on the eyebrow center (shaambhavi mudraa). Hold for the number of maatraas as described above (ie. 1.5 the comfortable number from the “preparation” section)

Slowly lower your head back to the normal position.

Exhale slowly in a controlled fashion for the number of maatraas as described above (ie. 1.5 times the number from the “preparation” section), removing all the air from your lungs within the count.

This is one round. As before, breathe normally for a few minutes before starting the next round, concentrating on the sensation of lightness and emptiness, and the transition of your mind to this state.

Repeat this for three rounds.

Over time, as you practice, you will find that you are able to hold your breath for longer and longer periods of time. When you notice that it is no longer challenging, increase the number of maatraas by ten.

Note: If you don’t know what a maatraa is, click here to learn more.

Another way of deepening this practice is to extend the number of rounds. For example, if you start with three, increase to four, then five, and so on.

Practising this technique prior to meditation helps to weaken the hold of distractions on the mind (ie. the next limb, Pratyaahaar).

However, be careful when practising, and stop if you feel uncomfortable or dizzy. The feeling should be one of lightness and emptiness, not one of dizziness.

Plaavini: Gulping breath

अन्तः प्रवर्तितोदारमारुतापूरितोदरः।पयस्यगाधेऽपि सुखात्प्लवते पद्मपत्रवत्॥Antah PravartitaUdaaraMaarutaApooritaUdarahPayasyaGadhe’Api sukhatPlavate padmaPatravatBy filling the inner part of the abdomen area with air, [the Yogi can] float on water like a lotus leaf.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 2.70

Plaavini comes from the root “plavana” (pronounced pluh-vuh-nuh), which means “to float.” It is named in this way because it is said that it enables the Yogi to float on water. It is also known as bhujangi mudraa.

The idea is that by gulping air into the stomach and intestines in a particular way, and retaining it there for an extended period of time, the digestive tract can become bloated like a balloon, enabling the Yogi to float on water.

This technique is particularly dangerous if not taught and practised properly. Given this, we will not discuss it in detail here, but it has been mentioned for the sake of completeness.

Until next time:

If you feel ready, practice moorchhaa. Remember to remain highly alert and attentive.

Take notes to see your progress, and your resilience to stress week over week.

Next time: Non-traditional Praanaayaam techniques: Vilom

There are several versions of this story. It seems it originated as an ancient greek myth, was adapted into various plays, dramas, and ballets through the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the 19th century, a rare disorder characterized by a loss of autonomic breath control came to be known as Ondine’s Curse. Today, it is known as Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome.