Consider the lilies of the field

Nowhere to go, nothing to do.

All questions are welcome - please submit your questions here:

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

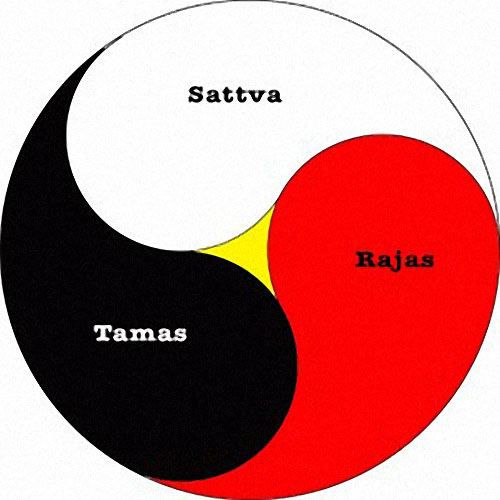

Everything in nature - every single thing that can be experienced - is made of nothing but the three gunas - sattva, rajas, and tamas.

Sattva is the quality of illumination, lucidity, knowledge, and calm.

Rajas is the quality of passion, movement, activity, and stimulation.

Tamas is the quality of dullness, inertia, obscuration, and heaviness.

All experienced things, from the quietest of thoughts to the rocks in space, as well as space itself, are nothing but these three gunas - threads, or qualities - in constant flux.

The mind, being an experienced object, is also made of these three gunas. When it is more sattvic, we feel calm, clear, and happy. When it is more rajasic, we feel desirous, restless, and agitated. When it is tamasic, we feel dull, fuzzy, slow, or tired.

Sattvic mental states are described in terms of openness, largeness, and infinitude - “She welcomed them with open arms”, “He has a big heart”, “They are open-minded.”

On the other hand, rajasic and tamasic mental states are described in terms of contraction, smallness, and narrowness - “She had closed herself off to new friends”, “My heart shrank”, “It made me feel small”, “Don’t be narrow-minded”.

These feelings are not just words - they are a matter of direct experience, and this is how they make their way into language.

Specifically, sattva is expansive - when it is dominant, the feeling can be described as “open”, “clear”, or “big.”

Rajas and tamas, on the other hand, lead to contraction. When they are dominant, the feeling is “small”, “narrow”, or “closed off.”

Through Yoga, we increase the proportion of sattva in the mind by clearing away rajas and tamas as one may remove the dirt from a mirror. This allows sattva to shine through, as sunlight shines through the clouds when a storm clears.

In this way, Yoga is not a process of adding, but rather a process of removal.

An ancient analogy compares this to a farmer who removes dirt embankments on the field in order for water to flow through. In the same way, the Yogi removes the blockages of rajas and tamas in order for sattva to flow, and therefore, for the mind to expand.

When rajas and tamas cloud the mind, they contract it, making it small. For example, we feel that we are this body - “I” only extend from the my head to my toes, and maybe to the tips of my fingernails. However, when we feel anxious, agitated, or sad, we feel contracted even smaller. On the other hand, when we culviate the Brahmavihaaras (e.g. compassion, friendliness, etc.), or we feel happy, ecstatic, or joyful, we feel expansive - beyond our bodies - like our love knows no bounds.

The removal of the veil over Knowledge

तदा सर्वावरणमलापेतस्य ज्ञानस्यानन्त्याज्ज्ञ्येयम् अल्पम्।Tadaa sarvaAavaranaMalaApetasya jnanasyaAnantyaatJnyeyam alpamThere [in Dharma-Megha Samaadhi] all the coverings and dirt over Knowledge being removed, there is little left to know.

- Yoga Sutra, 4.31

How do we know things?

Knowledge is of two types - knowledge of objects, and knowledge of the state of mind. That is, we know something, and we know we know it.

P: Don’t we also know that we know that we know?

Jogi: Certainly, but this is also knowledge of a mental state.

In Yoga, as we know, an object is defined as anything that can be experienced. Given this, the mind is also an object, and so there is really only one type of knowledge - knowledge of objects.

If we break it down, we find that there are three things in any act of knowledge - the knower, the thing to be known, and the instrument of knowledge which bridges them. This trinity is common to all knowledge.

The objects of knowledge vary - right now, you know the device on which you read these words, the words themselves, the meaning of these words, your surroundings, the language in which you read this, and so on. You know your memories, imaginations, perceptions, etc.

The instruments of knowledge also vary - you know the device through the senses of touch and sight, you know the meaning of these words through the buddhi, you know the sound of your surroundings through the sense of hearing, and so on.

The knower, however, seems to remain constant throughout all of these varied experiences. Whether you know the sounds around you, the meaning of these words, or your memories, it feels like there is a constant “you” that knows them all.

This is interesting. The things change, the instruments, change, but this third piece remains constant throughout.

This third piece - the knower - is the buddhi. This is the aspect of mind which knows, determines, decides, and distinguishes. The buddhi is the most sattvic aspect of mind, and in fact of all of nature. It is the first object of our experience, and the hardest to see as an object.1 It is mostly sattva, and is even referred to in the Yoga Sutra as simply “sattva.”

Ok, now back to how we know things.

Knowledge of an object happens when this sattva is limited by the object. That is, if we know the device on which we are reading this, what is really going on is that sattva is limited by the bounds of the device. When we know our thoughts, sattva becomes limited by the bounds of the thoughts.

This limitation - known as sankocha - is the result of rajas and tamas.

Rajas and tamas cloud the sattva in the mind like dirt covering a window. If you clear a small part of the window, you can see through it. Similarly, when the rajas and tamas are cleared away from the object, we can (as if) see through the sattva to experience the object. The more we remove the rajas and tamas, the more deeply we know the object.

We can experience this directly in meditation. If the mind is on the breath, but the mind is restless or dull, we still experience the breath, but not nearly as deeply or meaningfully as if the mind is calm and lucid. When the mind is calm and lucid, and we put our attention on the breath, we can experience it with a whole new sense of depth and clarity.

This is true for any knowledge.

If we watch a movie when we are distracted or tired (ie. rajasic or tamasic), we may not notice the small details. However, if we watch the same movie when the mind is calm (ie. sattvic), we notice everything much more clearly, and it is far more enjoyable like looking at a view through a clean window.

The more we remove the veil of rajas and tamas, the more deeply we know. Taking this to its logical conclusion, if rajas and tamas are completely cleared, we know completely.

P: Wait a second, how can rajas and tamas be completely removed? Don’t sattva, rajas, and tamas always coexist?

Jogi: That is correct! Rajas and tamas cannot be completely removed from sattva - only the proportions are different. In this way, within the mind, we cannot actually reach the logical conclusion of knowing “completely”. However, we can reach a stage where there is very little left to know.

Our whole lives, we seek experience - the experience of new sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures, the experience of new ideas, memories, imaginations, even the experience of sleep.

Experience - aka knowledge - is the magnet to which we are drawn, as moths to a flame. We feel that this will fulfil us, but we find - most often the hard way - that it never does.

Normally, we run after these experiences by using our karmendriyas - we employ our abilities to move, grasp, speak, and so on - to chase knowledge in the external world. However, this knowledge is simply sattva. We chase objects in order to remove the coverings of rajas and tamas, when we could have removed the rajas and tamas through Yoga - without running around the hamster wheel. What’s more, we can do it more efficiently, and more sustainably.

Through the practice of Yoga, we eventually reach its conclusion, when the rajas and tamas have reached their minima, and sattva is shining nearly unlimited. This results in a great feeling of vastness and contentment, since there is little left to know - minimal covering left to uncover.

The Purpose of Life is fulfilled

पुरुषार्थशून्यानां गुणानां प्रतिप्रसवः कैवल्यं स्वरूपप्रतिष्ठा वा चितिशक्तिरिति।PurushaArthaShoonyaanaam gunaanaam pratiprasavah kaivalyam svaroopaPratishtthaa vaa chitiShaktirItiKaivalyam is when the gunas involute, void of any purpose for the Purusha. In other words, [Kaivalyam is when] the power of Consciousness is situated in its own true nature.

- Yoga Sutra, 4.34

We have previously discussed the various levels of depth of Samaadhi, wherein the object of meditation is made progressively more subtle. For example, the initial object may be the breath. At the next level of depth, the object is the texture and sound that compose the breath - after all, what is breath but texture and sound?

This texture and sound, at a deeper level, are seen as nothing but configurations of the senses of touch and hearing, which are further seen as nothing but configurations of attention, and so on, just as a clay pot is nothing more than a configuration of clay, or a Play-doh person is nothing more than Play-doh, through and through.

Each level of depth is more sattvic than the last, and so more expansive than the last.

P: Why is it more expansive as we get more subtle?

Consider the first two levels. We begin with the breath - the breath is in a particular location, at a particular time.

As we go deeper, the object becomes texture and sound. Breath is, after all, nothing but texture and sound in a particular configuration. Breath is only one, limited, configuration of texture and sound, but there are many more possible configurations of texture and sound that appear in our experience.

For example, if you rub your hands together with your eyes closed, there is a texture and a sound - the “rubbing of hands with eyes closed” is in fact nothing more than another configuration of texture and sound.

In this way, “texture and sound” as objects (aka the tanmaatras of sparsha and shabda) are less contracted - less limited - than the specific object of “breath” or “rubbing of hands with eyes closed.” The more gross, or specific, an object of knowledge, the more contracted or limited it is. The more subtle, or generic, the object is, the less limited.

When we discussed the levels of depth, we found that all objects of experience ultimately boil down to the buddhi. Said another way, all objects of experience - including the various functions of the mind - are nothing but the buddhi in different configurations.

Given this, the buddhi - aka sattva - is the most subtle, or least contracted - of all experienceable objects.

Then, we saw that even the buddhi can be seen as a combination of the gunas - a constant stream of moments with no through-line. When this experience occurs, the gunas themselves are seen to be a projection - like a rabbit in the clouds - and so the “rabbit” disappears. That is, the projection ceases altogether - there is no more story to be taken seriously.

At the very beginning this series, we discussed the purpose of life - the four Purushaarthas. These are not things that one should do, but rather observations of what we tend to do. The four goals were Dharma (”doing the right thing”, or “doing good”), Artha (money, power, wealth, material possessions), Kaam (following desire, pleasure), Moksha (Liberation).

At this stage, when all of experience is seen to be nothing more than a projection, the Realized Yogi no longer strives after any of these. There is nothing more to be done, or rather, there was never anything special to do.

It is seen that just like the flowers grow, or just like the wind blows, we blossom, we think, we move, we love, we hate, we fight, we stress, we suffer, we laugh, and so much more.

We clearly see that our lives are of the same order of meaning as the patterns in leaves or the sound of the rain - there is no mistake, no misstep - everything is perfect, just as it is.

“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they toil not, neither do they spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.”

- Matthew, 6:28-29

Next time: The Prescription

It is because of the difficulty in distinguishing the Self from the buddhi that the question of “free will” arises. We feel like we are the doer, the decider, and the mental experiencer - all functions of the buddhi.