If you are reading this in your email, click on the title to see the full article in your browser, or you can click the link below to get the Substack app.

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

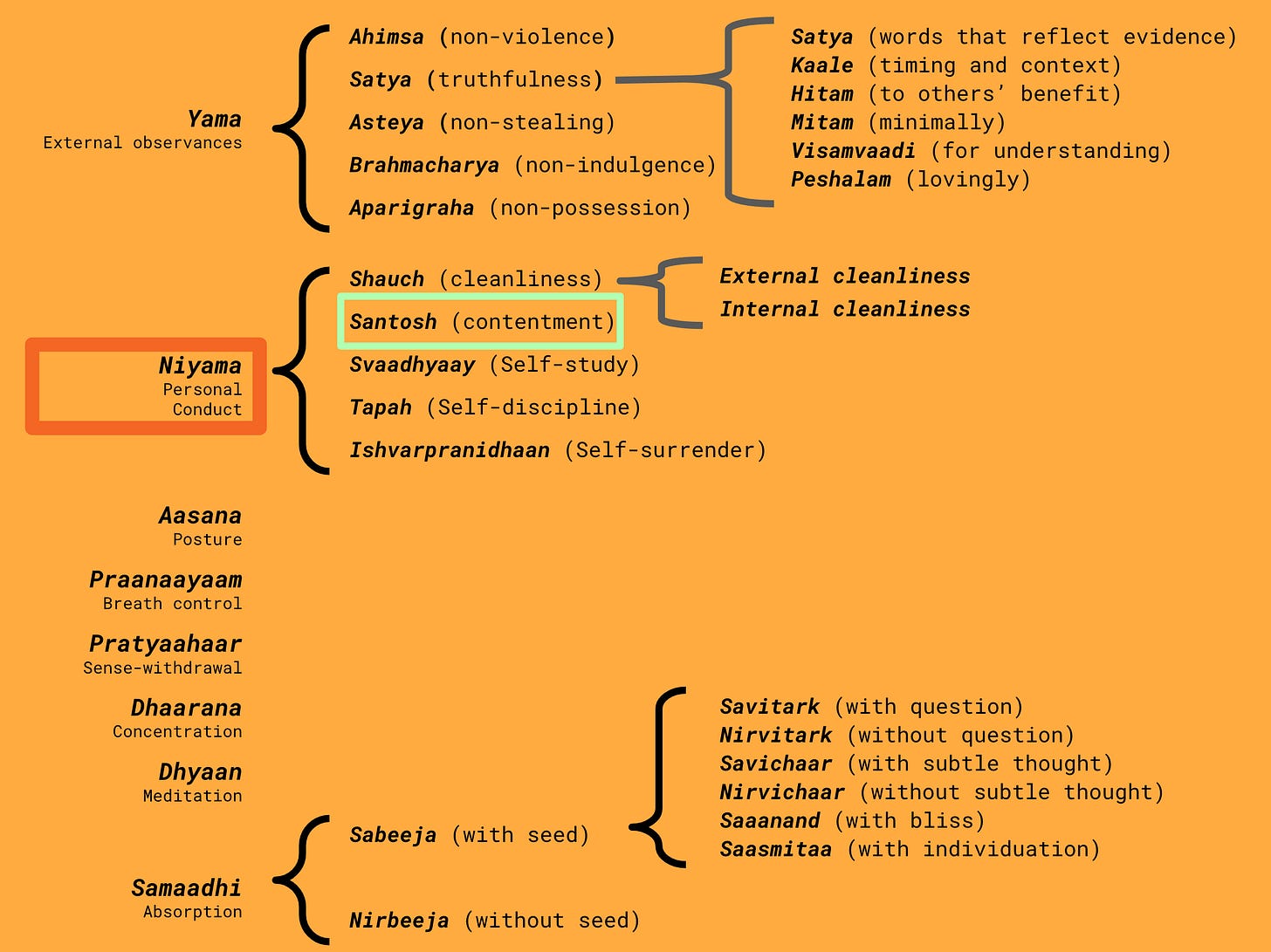

Last week, we started a discussion on the five Niyamas - the second limb of Yoga.

As a recap, they are:

Shauch: Cleanliness

Santosh: Contentment

Tapah: Self-discipline

Svaadhyaay: Self-study

Ishvarpranidhaan: Self-surrender

The goal of the Niyamas is to simplify one’s personal conduct so that it is no longer a distraction, such that the Yogi can move their attention further inward.

Our minds are conditioned to be tilted outward towards the objects of the world, and so, for the Yogi, an intentional effort must be made to tilt the mind inward, so that attention flows towards the Self rather than away from it.

This week, we will begin a discussion on the second of these Niyamas - santosh, and will continue it next time as well.

Santosh (pronounced sun-toe-sh) means “contentment”, and is defined by Vyasa as not wanting more than what one has. It is one of the most critical parts of the journey, especially for those of us who are conditioned from an early age in the culture of “more.”

However, before rushing blindly into the practice of santosh, it is important to understand the problem that it is solving - trishnaa, or “thirst.”

Trishnaa: The Thirst

As we have discussed previously, most of us run around our whole lives looking for that next thing that we feel will finally bring us happiness. We want more money, more cars, more space, more pleasure, more power, more love, more approval, more friends, and so on. There is no limit to our desires. This urge to get more goes further than our long term plans and goals, extending to every moment of our lives.

Even right now as you read this, you likely have a list in your mind - whether well-formed or not - of the things you need to do and the places you need to go once you have finished reading this, whether work-related or “recreational.”

Now the problem isn’t so much in desire itself, but in our relationship to desire. We suffer not because we desire, but because of the urge to fulfil our desires - whether we act on it or not.

The term for this urge to fulfil our desires - gross or subtle - is called trishnaa (pronounced trih-sh-naa), or thirst.

If this description doesn’t ring a bell, try this experiment: Set a timer for 20 minutes, and sit silently with your eyes closed. Do you feel an urge to get up, adjust your body, or to open your eyes and check the time? This urge is trishnaa in action.

This is not a matter of theory - we can directly experience trishnaa in the urge we feel to look at our phones, scroll through our feeds, shop for new stuff, or find the next place to go. Trishnaa permeates our entire lives - whether we know it or not.

It is as though we are constantly thirsty, looking for something to quench our craving once and for all. As a result of this thirst, we feel that we must have that next thing, because if we don’t, we will remain unfulfilled.

We feel a deep and desperate urge to fill up our cups, rather than empty them.

Having said this, it is a matter of common experience that satisfying desires brings happiness. This is certainly true.

However, this kind of happiness has three defects. In particular, it is:

Limited

Temporary

Unsustainable

In Vedanta, this type of happiness borne of satisfying desires is known as vishayaanand (pronounced vi-shuh-yaah-nun-duh). This can be translated as “object-bliss”, “object-satisfaction”, or “object-fulfilment.” For the purposes of this series, when the word “happiness” is used, it can mean either of these three translations.

Let us go through some of the problems with this type of happiness.

Vishayaanand is limited

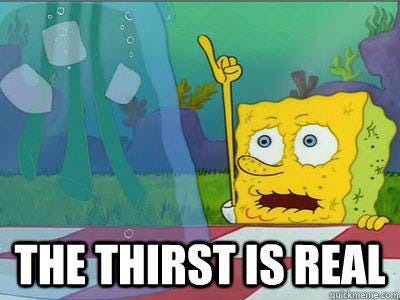

Vishayaanand is limited by its very nature. As we have discussed previously, it is surrounded by the threefold suffering of acquisition, preservation, and destruction objects (we suffer when we want them, we suffer to retain them, and we suffer when they are gone). As a result, no matter how amazing the pleasure may be, it is ultimately shrouded by suffering as honey mixed with poison.

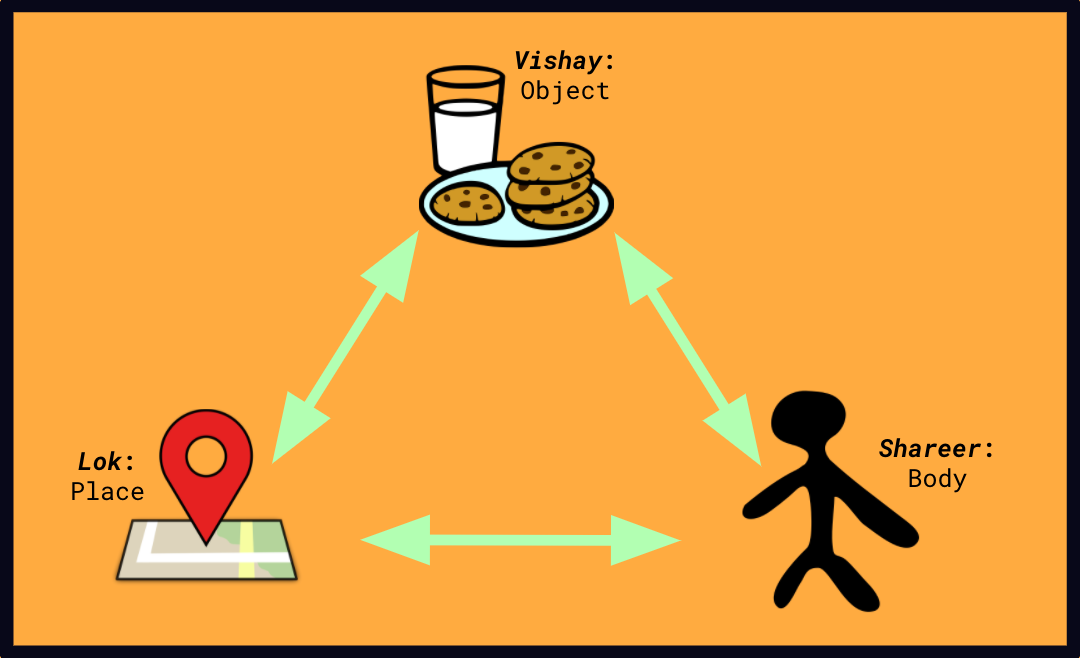

Additionally, the level of happiness one can attain from satisfying a desire is tied to more than the object itself, extending to the environment and the instruments of enjoyment. In this way, vishayaanand is limited by its component parts.

To be clear, there are three factors that play a part in the happiness derived from objects:

Vishay: The object itself

Lok: The place in which the object is enjoyed

Shareer: The body through which the objects are enjoyed

Let us begin with the first factor - vishay, ie. the object itself. As a matter of definition, objects extend beyond physical objects to mental objects like power, ideas, knowledge, credit, health, goodness, and so on. Anything you can refer to as “this” comes under the umbrella of “objects” for the purposes of Yoga and Vedanta.

Objects are the most obvious factor of happiness, wherein different objects result in different levels of enjoyment. We know this because when we keep the other two factors constant and change only the object, the amount of happiness changes.

For example, if you were to satisfy your desire for a chocolate chip cookie while sitting in your house, you get some level of happiness. Now let us switch the object around and see how it compares, while keeping the person (ie. you) and the location (ie. your house) constant.

Try this thought experiment: If the chocolate chip cookie gives you one unit of happiness, how many units of happiness do you get from each of these objects? Twice as much? Three times as much? Or more?

A new phone

A new relationship

New knowledge (e.g. an answer to a question you have been pondering)

A promotion at work

As you can see from this experiment, for the same person, in the same place, different objects will bring different levels of enjoyment. In this way, vishayaanand is limited by the object of desire.

Now let us move on to the second factor, lok (pronounced low-k). This refers to the place where the object is enjoyed. To investigate this factor, we will use the same method as we just used for vishay, where we keep the other two factors the same, and vary the factor we are inquiring about.

Consider the example of a meal eaten in your apartment. Remember to keep the meal constant - perhaps it is a salad, or maybe some dal and rice. Now let us consider that eating this meal in your apartment generates one unit of happiness in your mind.

Try this thought experiment: If eating it in your apartment gives you one unit of happiness, how many units of happiness do you get from eating the same meal in the following places?

The pavement outside your house

Inside a car while sitting in traffic

A fancy restaurant overlooking a beautiful view

You may notice how varying the location changes the level of enjoyment even for the same object, and for the same person.

A very real example of this is how a meal served by the roadside or at a fast-food drive-through costs a fraction of the exact same meal served in a fancy restaurant. The reason for this is the ambience - we feel more enjoyment with the same object, with the same sense faculties, in different settings. This is a well recognised fact of our experience, and so it is reflected in the (often vast) difference in price.

In this way even inferior objects can produce a higher sense of vishayaanand in the same person, if the place is different.

Now on to the third factor - shareer (pronounced shuh-ree-ruh), or body. This includes the body, senses, and mind of the person who is enjoying the object.

The more refined the senses (the more sattvic they are), the more the sense of enjoyment, even when the location and the object are the same. In simple terms, the way we usually refer to more sattvic senses is when we say that someone has a “taste” for some type of object (e.g. they have good taste in clothes, good taste in art, good taste in food, music etc.).

Let us consider an example using the same method of inquiry, where we keep two factors constant and vary only the factor in question. Keeping the object (vishay) and location (lok) constant, we vary the person who is enjoying it. Let us imagine different people at a concert. One person listens to music sometimes, but not often. This can be our baseline of one unit of happiness.

Try this thought experiment: Consider one unit of happiness to be the amount of pleasure experienced by the regular person (listens to music sometimes) at a concert. Now compare this to the enjoyment of the following people with the same object (a song played at the concert) in the same location (the concert venue):

A person who listens to music every day

A person who is trained in music, or a professional musician

A person who cannot hear (ie. their hearing is impaired in some way)

Notice, how the level of enjoyment for these people varies, even though the object and the location are both exactly the same. The reason for this is that the level of subtlety (sattva) in their sense of hearing is different from one another. The more sattvic the senses, the more the enjoyment - even when the object and the location are the same.

While this example related to a piece of music played at a concert venue, this same reasoning can be extended to any pleasure at all. For example, consider wine as enjoyed by a sommelier, food as enjoyed by a chef, football as enjoyed by someone who plays football, or art as enjoyed by an artist.

This phenomenon is beautifully summarised in this famous Sanskrit verse:

गुणी गुणं वेत्ति न वेत्ति निर्गुणो, बली बलं वेत्ति न वेत्ति निर्बल: ।पिको वसन्तस्य गुणं न वायस: करी च सिंहस्य बलं न मूषक: ॥Guni gunam vetti na vetti nirguno, bali balam vetti na vetti nirbalahPiko vasantasya gunam na vaayasah, kari cha sinhhasya balam na mooshakahThose with the quality appreciate the quality [in others], those without the quality do not.

Those with strength appreciate the strength in others, those without strength do not.

The cuckoo appreciates the spring, while the crow does not.

The elephant appreciates the strength of the lion, while the mouse does not.

In this way, no matter how much you may want something, know that the happiness you will get from it is limited by your body, your senses, your mind, and your capacity to enjoy it. No object can bring happiness that is not limited in one way or another.

Vishayaanand is temporary

All objects are impermanent. More than this, they are constantly changing, never the same from one moment to the next. Additionally, the other factors of enjoyment (body and location) are also impermanent.

As a result, happiness from objects (vishayaanand) is temporary as well.

Try to remember a time that you wanted something, and spent significant time and effort to acquire it. At first, when you got it, there was some enjoyment. Perhaps it was a job that you wanted, a relationship with a person, money, a house, knowledge, or anything else that you felt would bring you happiness. Now notice, if you no longer have this object, the enjoyment from it has faded, or even perhaps turned into suffering.

What’s more, even if this object has somehow remained in your possession, your initial enjoyment from it has reduced over time. This is either because the object, the location, or your body and mind have changed, as is the nature of all things.

All the things that we want, and spend so much effort to acquire and enjoy, will change or disappear one day. As a result, all vishayaanand is limited by the temporary nature of the three factors of enjoyment.

Vishayaanand is unsustainable

We have now gone over how vishayaanand (ie. happiness from objects) is limited and temporary. However, this kind of happiness has yet another defect.

Because the burst of happiness from objects is temporary, and because our thirst for happiness is insatiable, the moment the happiness from objects wears away, we feel the thirst (aka trishnaa) yet again. As a result, we run off in all directions trying to satisfy it, and end up spending our entire lives trying to fill a bottomless pit.

Aside from all this, by satisfying desires, we are strengthening the klesha of raag (colouring/affliction of attraction) in our mind. The reason for this is that every time we follow a tendency, we are training our mind to follow that same tendency again in the future. This is similar to how pouring water on soil in the same place repeatedly will create channels in the soil, so that when the next time water is poured, it will follow those same channels.

In simple terms, the more you satisfy desires, the more you want to satisfy them. In this way, desire is like a fire, and satisfying the desires is like fuel.

This is summarised in the following verse from the Bhagavad Gita:

आवृतं ज्ञानमेतेन ज्ञानिनो नित्यवैरिणा |कामरूपेण कौन्तेय दुष्पूरेणानलेन च ||Aavritam jnaanamEtena jnaanino nityaVairinaakaamaRupena Kaunteya dushpoorenAanalena chaThe knowledge of even the wisest of the Jnaanis (ie. the Knowledgeable ones) is shrouded by the Great Enemy called Desire, which appears in the form of an insatiable fire that cannot be quenched.

- Bhagavad Gita, 3.39

Let us quickly summarise what we have gone over.

It is a matter of direct experience that we feel a deep sense of thirst for fulfilment. It is also a matter of direct experience - if we are honest with ourselves - that we never really feel fulfilled, no matter how hard we try. This constant and unquenchable thirst is called trishnaa.

In our ignorance - aka avidya - we try to satisfy our thirst with objects, because that is what we have been conditioned to do.

However, while this does give us some relief, this kind of happiness - called vishayaanand - is ultimately unsatisfactory due to its three defects, in that it is:

Limited

Temporary

Unsustainable

Knowing this to be true, it is clear that happiness from objects does not really work, just like one cannot put out a fire with gasoline.

P: So then what do we do?!

This is where santosh, or contentment comes in. It is the second of the five Niyamas, and will be the subject of our discussion next time.

Until next time:

Think of something that you now have, that you once wanted terribly. Do you feel fulfilled now that you have it, or do you still feel a sense of trishnaa for more, or for different objects?

What are the objects you chase for fulfilment? These could be small or big, physical or mental. Write these down.

How often do thoughts about these objects arise? Notice them as they arise, and notice how often you act on them. Do these thoughts make you feel good, bad, or neutral?

As always, please do not hesitate to reach out with questions, comments, objections, or feedback. Additionally, feel free to share your notes from the exercises here in the comments section or anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup. Finally, if you are enjoying this series, feel free to share it with anyone who you feel may be interested.

Next time: How to be content