Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

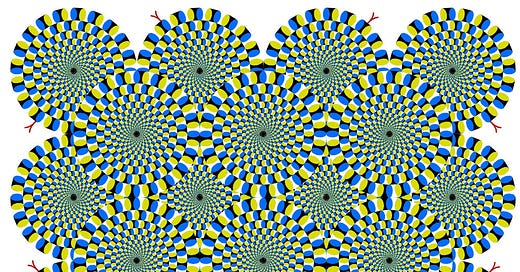

Look closely at the image below. Do you notice movement?

Now try not to blink, and stabilize your eyes in such a way that the movement in the image completely stops. How long can you keep your eyes still in this way? Did your breathing change?

This practice of stabilizing the motion of the eyes and controlling the blink-reflex is called traataka (pronounced “traah-tuh-kuh”). Through stabilizing the eyes, the movement of thought slows down1, and the mind is prepared for meditation.

For the past several weeks, we have been discussing the shatkarmas. These are six categories of preliminary techniques to stabilize the Praana so that it is no longer a distraction, thus allowing the Yogi to move further inward towards the Self - the goal of Yoga.

This is the pattern of the eight-limbed path. Each limb stabilizes an aspect of the Yogi’s being such that it is no longer a distraction and can be dropped off, or let go (with vairaagya) in such a way that the Yogi is able to turn further inward with ease.

The shatkarmas are often taught alongside Praanaayaam - the fourth limb. Where the shatkarmas purify and strengthen the movement of the Praana, Praanaayaam allows the Yogi to control and observe the Praana. The shatkarmas are not necessary for everyone, but are helpful even if they are not needed.

As a reminder, the six shatkarmas are:

Nauli: Abdominal massaging

Kapaalbhaati: “Skull shining”

Traataka: Concentrated gazing

Traataka: Concentrated gazing

निरीक्षेन्निश्चलदृशा सूक्ष्मलक्ष्यं समाहितः।अश्रुसंपातपर्यन्तमाचार्यैस्त्त्राटकं स्मृतं॥NireekshenNishchalaDrishaa sookshmaLakshyam samaahitahAshruSampaataParyantamAachaaryaisTraatakam smritamLooking at a subtle/small goal/object without moving the eyes, with a gaze that is unmoving, until tears arise, is known by the teachers as Traataka.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 2.31

The movement of Praana is intimately tied with the movement of the mind. When the Praana moves, the mind moves; when the Praana is still, the mind also becomes still. In this way, being able to grasp and control the Praana is a powerful way to still the mind, such that it becomes prepared for meditation.

One of the five Praanas is called udaana. Amongst other things, it is responsible for the blink-reflex and the movement of the eyes.

Udaana is the most subtle of the five Praanas. When all the other Praanas are no longer a distraction, this Praana continues to present distractions to the mind. In fact, these distractions are so subtle that we often do not even realize that the mind has been drawn outwards.

The purpose of traataka is to be able to clearly notice this subtle distraction, and then to still the mind through the control of the eyes.

There are two forms of traataka:

Bahiranga: External traataka

Antaranga: Internal traataka

Both of these can be practised safely without supervision. However, the latter is more difficult than the former.

Bahiranga: External Traataka

Bahiranga, or external traataka uses an external object to stabilize the eyes. Any kind of small object can be used for this technique. Some common objects are:

A candle flame

A yantra

A dot

The Moon

A star

The symbol of Om (ॐ)

The image of a deity (specifically the Yogi’s ishta-devataa)

One’s own shadow

The common feature of these objects is that they are steady.

This is important, because if the object is moving, the eyes will need to move in order to maintain focus - however, the purpose of traataka is to keep the eyes steady.

Another feature of these objects is that they are either uplifting or neutral, and do not elicit any kleshas in the mind. For example, one should not use an object if it elicits fear, lust, greed, envy, sense-attraction, aversion, selfishness, etc. The reason for this is that kleshas, like any thought pattern, are strengthened with repetition. One of the goals of Yoga is to weaken and eventually remove the kleshas, and so eliciting the kleshas in the mind can be counterproductive.2

If you wear glasses, you can remove them prior to practising this technique.

Warning: If you suffer from dry-eye syndrome - do not try this practice. Research has shown that dry-eye syndrome is most common amongst post-menopausal women, and manifests itself as redness or inflammation of the eyes.

Following is the technique:

Select an object that fits the criteria above. It should be steady and neutral or uplifting.

Find a room that is free of insects, wind, and any other moving objects (including a TV or computer screen with video playing on it).

Sit in your Aasana, placing the hands on the knees. The body should be completely still and relaxed - no fidgeting, scratching, or wiggling!

Close your eyes and take five to ten deep breaths using the Deergha Shvaasa technique.

When the mind is a bit more calm, open the eyes and steady them on the center of your object. If you are using a flame, focus on the part of the flame just above the wick.

Keep your eyes absolutely steady, without blinking. If the urge to blink arises, lower your eyelids slightly, keeping the eyeballs completely steady. Hold the gaze for between five and ten minutes (increase this with practice). You may notice that the image starts to become fuzzy - this is a sign that your mind is starting to wander. Retain the sharpness of the image! Notice your breath - has it become more subtle?

Close the eyes and notice the after-image of the object in the blank space of your mind. Gaze at this mental image. If you find the image moving, bring it back to the center and study it carefully - notice the colour, the shape, and the background.

If a thought arises, let it pass without getting involved, holding the focus on keeping the eyes steady.

Keep the eyes closed until the image disappears, and repeat.

This is one cycle.

When gazing at the external object, you will notice at first that the eyes are prone to move around quite a bit. As you continue to gaze, you will find that the eyes become steadier.

However, once your mind becomes sufficiently calm, you may also notice that your eyes involuntarily flicker ever so slightly.

These flickers of the eye are called “saccades.” The eyes only capture small slices of information at a time. To create an image of our surroundings, the eyes move around, and the brain puts all these slices together to form the image of the space around us.

To make this clear, imagine walking into a room for the first time. At first, you look around to get a high-level understanding of the space. This usually includes the layout, the walls, the floor, large objects, and any people. At the next stage, the mind starts to hone in on certain objects. For example, you may notice a friend sitting in the corner of the room, or see a book on the bookshelf which looks familiar or interesting to you. We rarely get more detailed than this - perhaps when we are studying a piece of art, or when we are searching for a small object. However, as a result of this “glossing over”, we tend to ignore a large amount of information.

This “glossing over” has a more insidious effect too. By not paying attention, the mind abstracts the visceral experience of objects into verbal symbols (ie. words). For example, rather than looking deeply at the beauty of a flower as we walk past it, we quickly pass it off as “flower”, and move on to the next thing.

If we do this enough, we end up living in a world of these abstractions, and everything starts to feel dull, hollow, and empty. We have discussed this in some detail in the article on the obstacles to Yoga, here.

Through regular practice, the world starts to feel brighter, more visceral, and more full.

Through the practice of traataka, these otherwise involuntary flickers of the eye can be controlled, leading to a calmer mind, and more attention to detail.

Tip: During the practice of traataka, when the mind calms down you will notice the eyes slightly flickering. When you notice this, lengthen your exhalations to steady the eyes even further.

You will know that you are successful when all objects except your chosen object disappear - it should feel like the entire Universe has dissolved. No other object will be visible to you. This is called the Troxler effect. You can try this by performing traataka on the cross in the center of the image below - notice how the face disappears.

Sometimes, the entire visual field, including the object can vanish. Other times, hallucinations can start to appear. This is called the Ganzfeld effect. When this happens during a traataka session, it can be somewhat frightening at first - this fear will pass. Continue on with the practice and you will find that the mind becomes completely steady, and that this steadiness continues into your day.

Additionally, practising traataka just prior to meditation enables the Yogi to go deeper, faster.

Antaranga: Internal traataka

In antaranga traataka, the support of an external object is no longer necessary. This technique takes a lot of practice, so don’t worry if it doesn’t work for you the first time around.

The technique is as follows:

Select a mental image that is steady and neutral or uplifting. Using the same object that you used for external traataka will provide quicker results.

Sit in your Aasana, placing the hands on the knees. The body should be completely still and relaxed.

Close your eyes and take five to ten deep breaths using the Deergha Shvaasa technique.

Bring the image to your mind and try to visualise it in as much detail as possible. It should appear clearly before you. If this does not happen immediately, start with a portion of the object - the simpler the object, the easier it will be.

Center the image and make it as steady as possible, and watch it closely, noticing the details and the background.

The manas has the tendency to oscillate back and forth between objects. This is most clearly experienced when we have to choose between two things, as in this meme below.

This oscillating tendency results in feelings of worry, anxiety, and even sadness and dejection. If we make a habit of living in this way, we can start to feel like the world around us is hollow and empty.

Through the practice of traataka, the mind becomes steady, and we start to notice small details which we had previously missed. As focus increases, so does memory and will-power.

Finally, the practice of traataka helps to stabilize the mind for meditation. With sufficient practice, distractions simply melt away, and attention that was otherwise dissipated through the motion of the eyes becomes available for the intense focus required for the next few limbs of Yoga.

Until next time:

Practice bahiraanga (external) traataka using the steps above. Slowly extend the time you spend with eyes open, as well as the time it takes for the image to disappear with eyes closed.

Optional: Practice antaranga (internal) traataka.

Take notes to see how the mind feels before and after traataka. Do you feel more focused, calm, and decisive?

As always, feel free to reach out with questions or comments by responding directly to this email, in the comments section below, or anonymously at r/EmptyYourCup.

Next time: Praanaayaam: “Box Breathing” (aka Samavritti Praanaayaam)

When the mind slows down, so does the breath.

चले वाते चले चित्तं निश्चले निश्चलं भवेत् ।योगी स्थाणुत्वमाप्नोति ततो वायुं निरोधयेत् ॥Chale vaate chalam chittam nishchale nichalam bhavetYogi sthaanutvamAapnoti Tato Vaayum NirodhayetWhen the Praana moves, the chitta moves. When the Praana is still, the chitta is still.

By the steadiness of Praana, the Yogi attains steadiness. Therefore, master the Praana.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 2.2

This is not always the case. There are situations in which one may want to use an aversive object for traataka, but it is under very specific circumstances wherein the technique is used to weaken existing kleshas.