Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

Now, the senses argued amongst each other, each saying, “I am the best of us all.”

They went to Prajaapati, their father, and said, “Sir, who is the best among us?”

Prajaapati said, “He on whose departure the body looks the worst, he amongst you is the best.”

Speech went forth, and having stayed away from a year, returned and asked, “How did you fare without me?”

[The senses replied], “Just like one who cannot speak, not speaking, but breathing with the Praana, seeing with the eye, hearing with the ear, and thinking with the mind.”

Disappointed, Speech re-entered the body.

Sight went forth, and having stayed away for a year, returned and asked, “How did you fare without me?”

[The senses replied], “Just like one who cannot see, not seeing, but breathing with the Praana, speaking with the speech, hearing with the ear, and thinking with the mind.”

Disappointed, Sight re-entered the body.

Hearing went forth, and having stayed away for a year, returned and asked, “How did you fare without me?”

[The senses replied], “Just like one who cannot hear, not hearing, but breathing with the Praana, speaking with the speech, seeing with the eye, and thinking with the mind.”

Disappointed, Hearing re-entered the body.

Mind went forth, and having stayed away for a year, returned and asked, “How did you fare without me?”

[The senses replied], “Just as a child, not thinking, but breathing with the Praana, speaking with the speech, seeing with the eye, and hearing with the ear.”

Disappointed, Mind re-entered the body.

Now the Praana was just about to depart, [and it was seen that] this would tear up all the other senses - just as a spirited horse might tear up the pegs to which he is tethered. The senses all gathered around him and said, “Sir, you are the best of us, please do not depart.”

Then Speech approached Praana and said, “Sir, that attribute of mine which is the most excellent actually belongs to you.” So said Sight, Hearing, and Mind.

Therefore, the senses are not merely sense organs - they are all signs of life - Praana.

For Praana alone is all these.

- Chhandogya Upanishad, 5.1.6-15

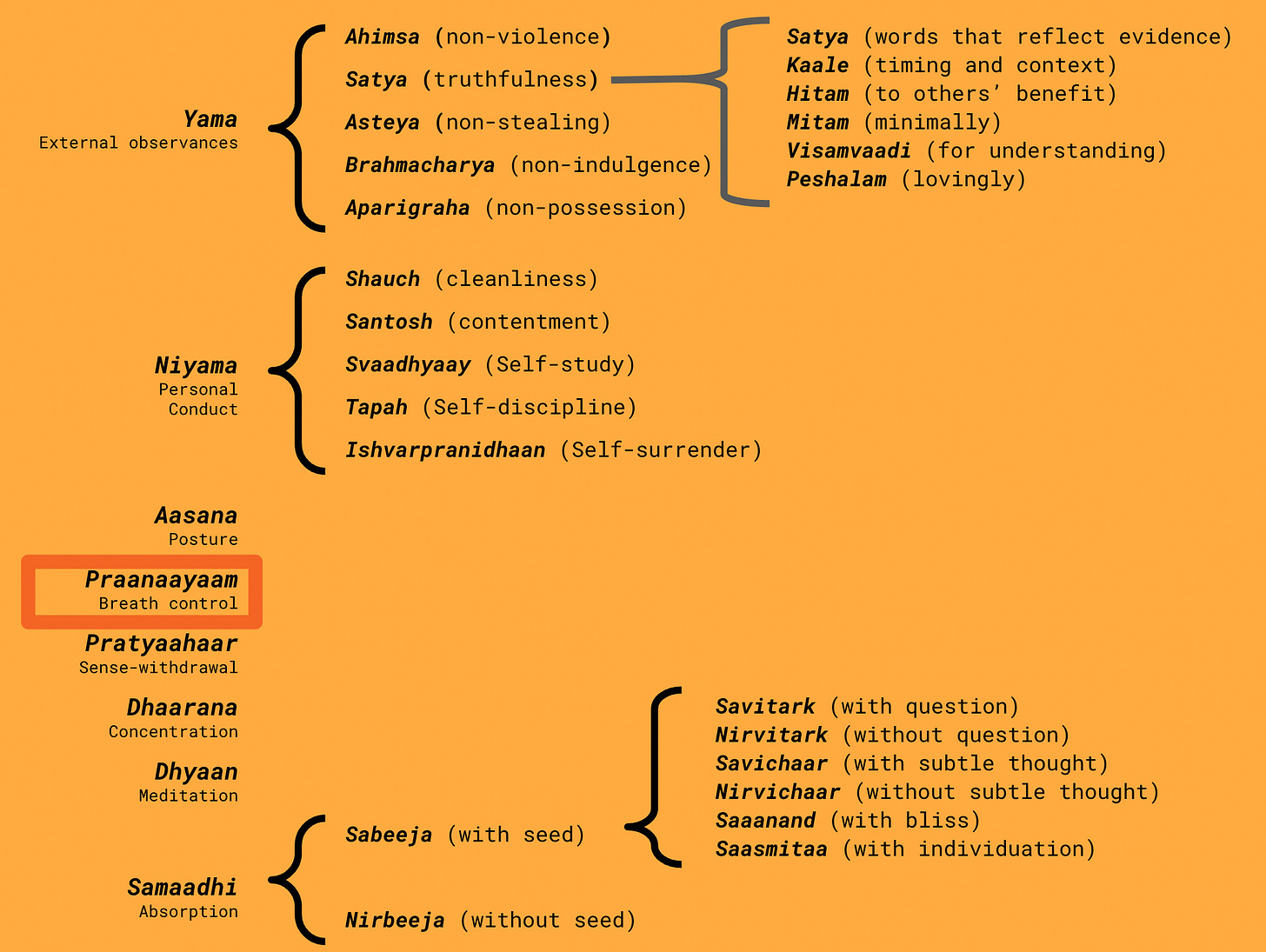

Over the past several weeks, we have been discussing the eight-limbed (Ashtaanga) Yoga. It begins with the Yamas, which deal with the most outwardly aspect of our being - our external interactions - and moves systematically inwards, dropping off each layer to move to the next.

Following the Yamas are the Niyamas, which deal with the next layer - our personal conduct. Next is the third limb - Aasana - which deals with the physical body. Once the physical body is sufficiently comfortable and still, the Yogi is able to let go of the body and move one layer inward to the Praana.

What is Praana?

Praana (pronounced praah-nuh) is often translated as “breath”, but is in fact something deeper. Literally, the word translates to “life” or “life force.” Sometimes, Praana is referred to as vaayu (pronounced vaah-you), which literally means “wind”, and is sometimes translated as “vital airs.”

यावद्वायुः स्थितो देहे तावज्जीवनमुच्यते।मरणं तस्य निष्क्रान्तिस्ततो वायुं निरोधयेत्॥YaavadVaayuh sthito dehe tavajJeevanamUchyateMaranam tasya nishkraantisTato vaayum nirodhayetAs long as Praana remains in the body, this is what is referred to as “life.”

“Death” is when [Praana] leaves the body. Therefore, master the Praana.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 2.3

Praana is not breath in itself, but rather it is that by which you breathe. We start our lives with an inhale, and end our lives with an exhale. Life is, in this way, counted not in time, but in the number of breaths from the first to the last. However, breath is only one of the many symptoms, or modifications, of Praana.

P: What do you mean “modification” of Praana?

A single piece of clay can be moulded into a pot, a plate, a cup, or a statue. These are modifications of clay. Similarly, Praana appears in the form of breath, digestion, procreation, circulation, and all the other life functions.

Notice, the clay never appears without a form - if nothing else, it is in the form of a lump of clay. Similarly, Praana always appears to us through its modifications.

What’s more, with practice, the Yogi is able to notice it as Praana, and even direct it at will.

Hatha Yoga has a number of practices through which the Praana can be controlled, refined, and directed around the body. There are countless stories - old and recent - of how accomplished Hatha Yogis are able to direct their circulation in and out of a given limb, or how they are able to completely stop breathing for hours at a time. However, in Raja Yoga, this kind of thing is not the goal.

Rather, Raja Yoga uses the fact that Praana is intimately connected with the mind (aka the chitta) to help the Yogi eventually transcend Praana altogether, and move further inwards towards the Self.

चले वाते चले चित्तं निश्चले निश्चलं भवेत् ।योगी स्थाणुत्वमाप्नोति ततो वायुं निरोधयेत् ॥Chale vaate chalam chittam nishchale nichalam bhavetYogi sthaanutvamAapnoti Tato Vaayum NirodhayetWhen the Praana moves, the chitta moves. When the Praana is still, the chitta is still.

By the steadiness of Praana, the Yogi attains steadiness. Therefore, master the Praana.

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 2.2

Otherwise, as with Aasana, there is a risk that the Yogi gets stuck on this limb by getting obsessed with physical feats, thus getting tied further to the body and strengthening avidya.

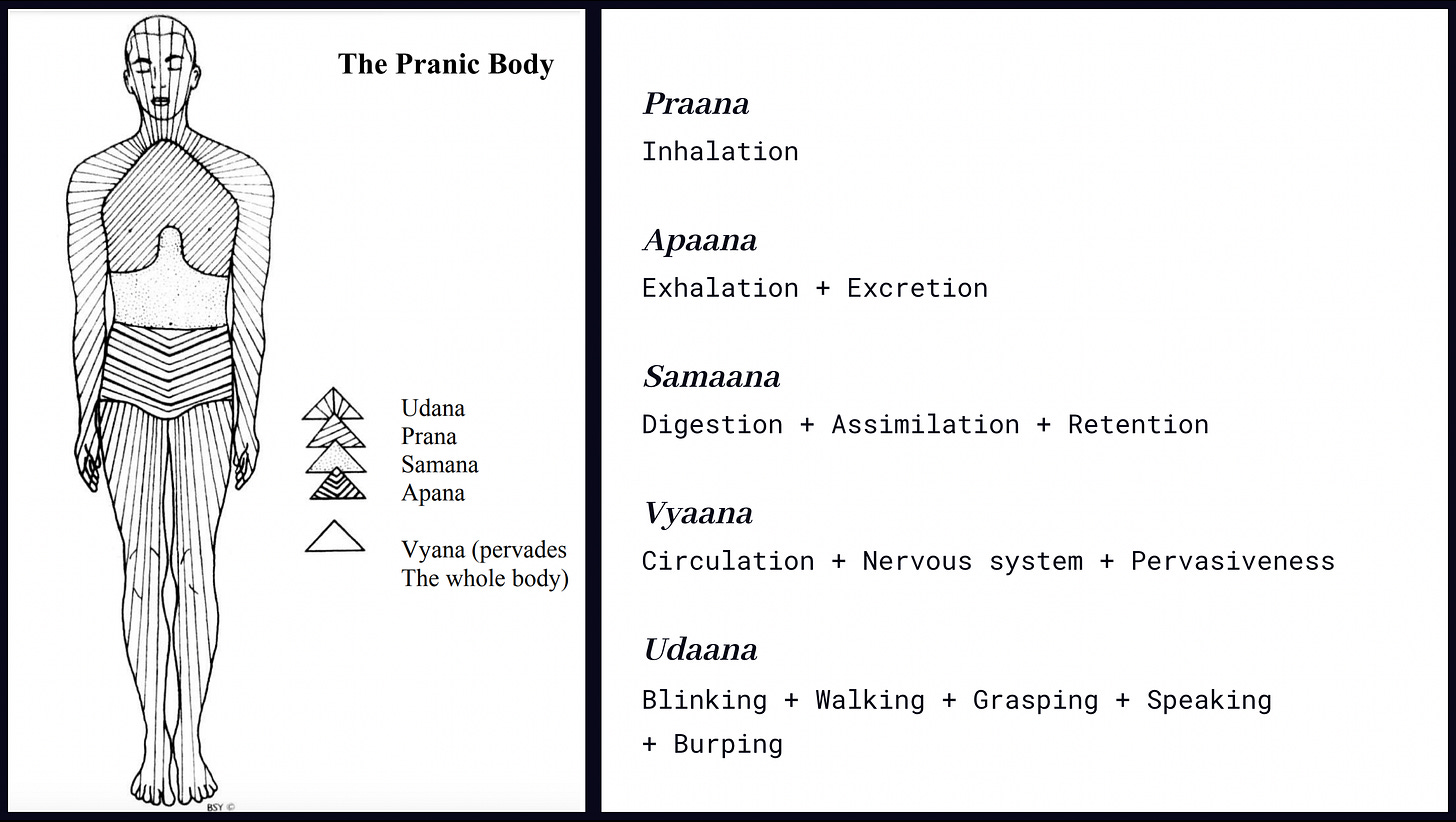

The 5 types of Praana

Depending on whom you ask, there are several different modifications of Praana. These differ from text to text, and school to school - there is no common consensus. This is likely because the distinctions of Praana stem from personal observation and experience of various Yogis over millennia, and there is no single source of truth. However, this should not be a hindrance. Any school will do so long as you get an understanding of what is meant by the term Praana.

The 5 main Praanas are:

Praana: Inhalation

Apaana: Exhalation + Excretion

Samaana: Digestion + Assimilation of nutrients + Retention of breath

Vyaana: Circulation + Nervous system + Anything that pervades the whole body

Udaana: Blinking + Walking + Grasping + Speaking + Burping

There are also 5 subsidiary Praanas, known as Upapraanas. Notice, there is some overlap with the first five:

Koorma: Blinking

Krikaara: Hunger + Thirst + Sneezing + Coughing

Devadatta: Sleep + Yawning

Naaga: Hiccups + Burping

Dhananjaya: Lingers immediately after death

Don’t worry, you don’t need to memorize these. They are just for the sake of understanding what Praana is, by way of seeing how it appears as the various functions of life in the body. Additionally, one may notice that although there is a tremendous focus on breath in Raja Yoga, breath is not the only Praana.

Note: The Praanas are not the functions themselves, but that by which the functions occur. This may not be immediately understood, but can be seen directly through practice.

One way to understand Praana is to try to find the experiential similarities between the different functions mentioned. For example, udaana is that which is common between blinking, speaking, and grasping.

Praanaayaam: Lengthening the Praana

The fourth limb of Yoga is called Praanaayaam (pronounced praan-aah-yaahm). Literally, it means “lengthening the Praana”, and while there are a number of specific exercises within this limb, there are some fundamentals which underpin all of them.

For the next few weeks, we will go over the fundamentals as well as some specific exercises.

तस्मिन् सति श्र्वासप्रश्र्वासयोर्गतिविच्छेदः प्राणायामः॥Tasmin Sati ShvaasaPrashvaasayorGatiVicchedah PraanaayaamahWhen [Aasana] happens, the regulation of inhalation and exhalation follows, through which the Prana is lengthened (ie. Pranayama).

- Yoga Sutras, 2.49

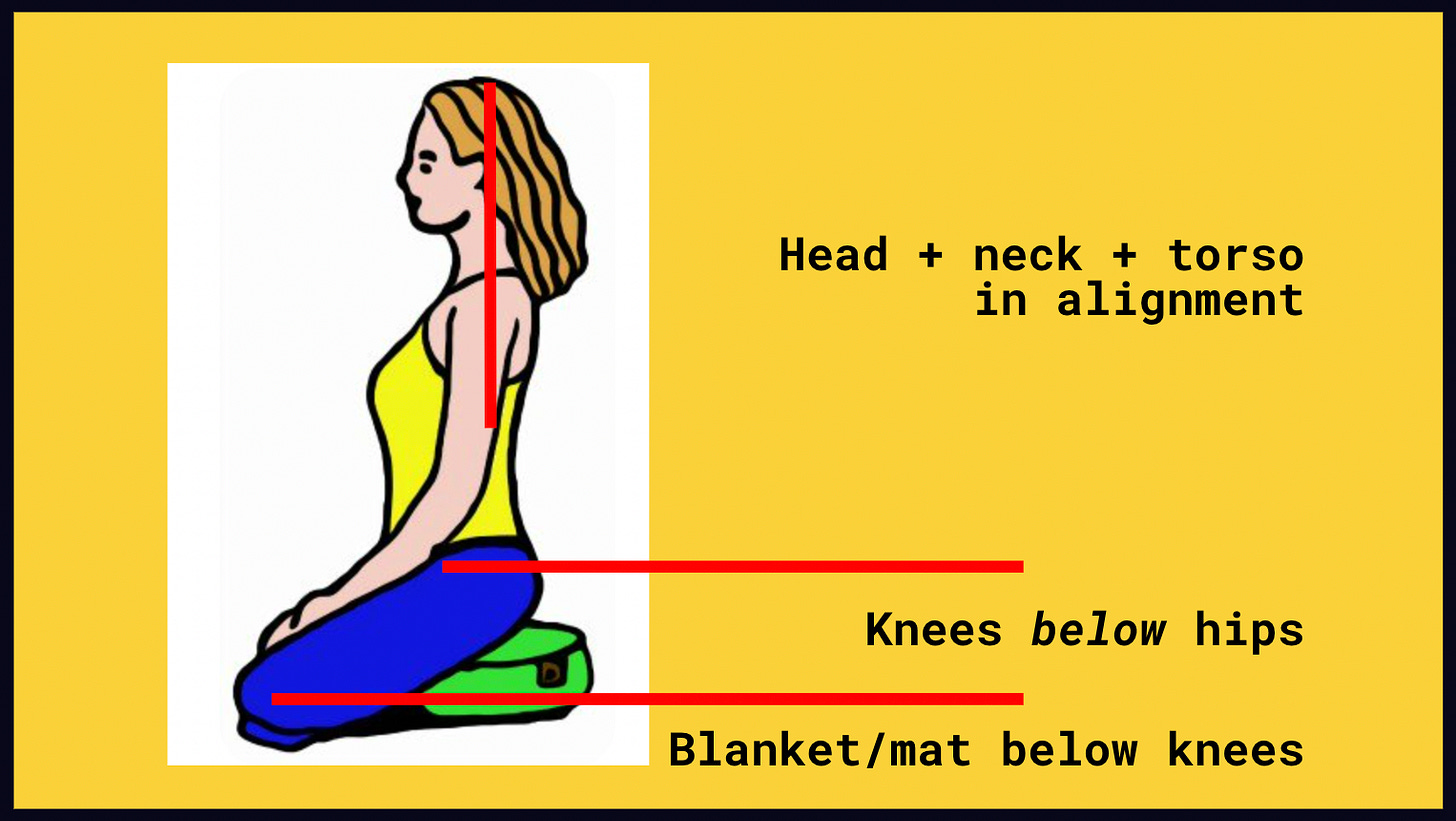

Praanaayaam follows from Aasana.

Practically speaking, this means that one should practice Praanayaam once they have properly established and settled into a seat which is stable and comfortable, such that the head, neck, and torso are in alignment.

This is extremely important, otherwise the practices may not have the intended effect.

Additionally, this means that the breath provides an indication as to whether you are established in your Aasana - you will know that your Aasana is stable when you feel the urge to take a deep breath, and are easily able to do so.

In Raja Yoga, Praanaayaam is the intentional regulation of the breath with the goal of making the breath long and subtle.

Notice the use of the word vicchheda in the sutra above.

Vicchheda means to cut, cleave, divide, limit, interrupt, pause, or regulate. In this way, Pranaayaam is not just about inhalation and exhalation, but also involves retention of the breath.

There is an additional meaning as well. When you cut something, it involves a deeper focus on the object. For example, imagine you are cooking, and as you are preparing the ingredients, you need to cut a carrot into two pieces. As you cut the carrot, the attention becomes naturally more focused on it.

Similarly, when practising Praanaayaam, the attention becomes naturally more focused on the breath, and the inner workings of Praana become experientially clear to the Yogi.

When going over the second limb - the Niyamas - we discussed how there are two modes of practice:

As a mahaavrat: At all times, all places, etc.

Limited by time and space: At a specific time and place

Praanaayaam is very similar in this way. While there are specific exercises that can be done at particular times of the day (e.g. just prior to meditation, just after Aasana practice, upon waking up, etc.), there is also a specific method of breathing which is to be practised at all times, and in all places, regardless of the circumstance.

This “all-the-time” practice is the basis for all other Praanaayaam techniques, and so it is important to get a good handle on it before moving on to other exercises involving the breath.

Deergha Shvaasam: Big Breath (aka Yogic Breathing)

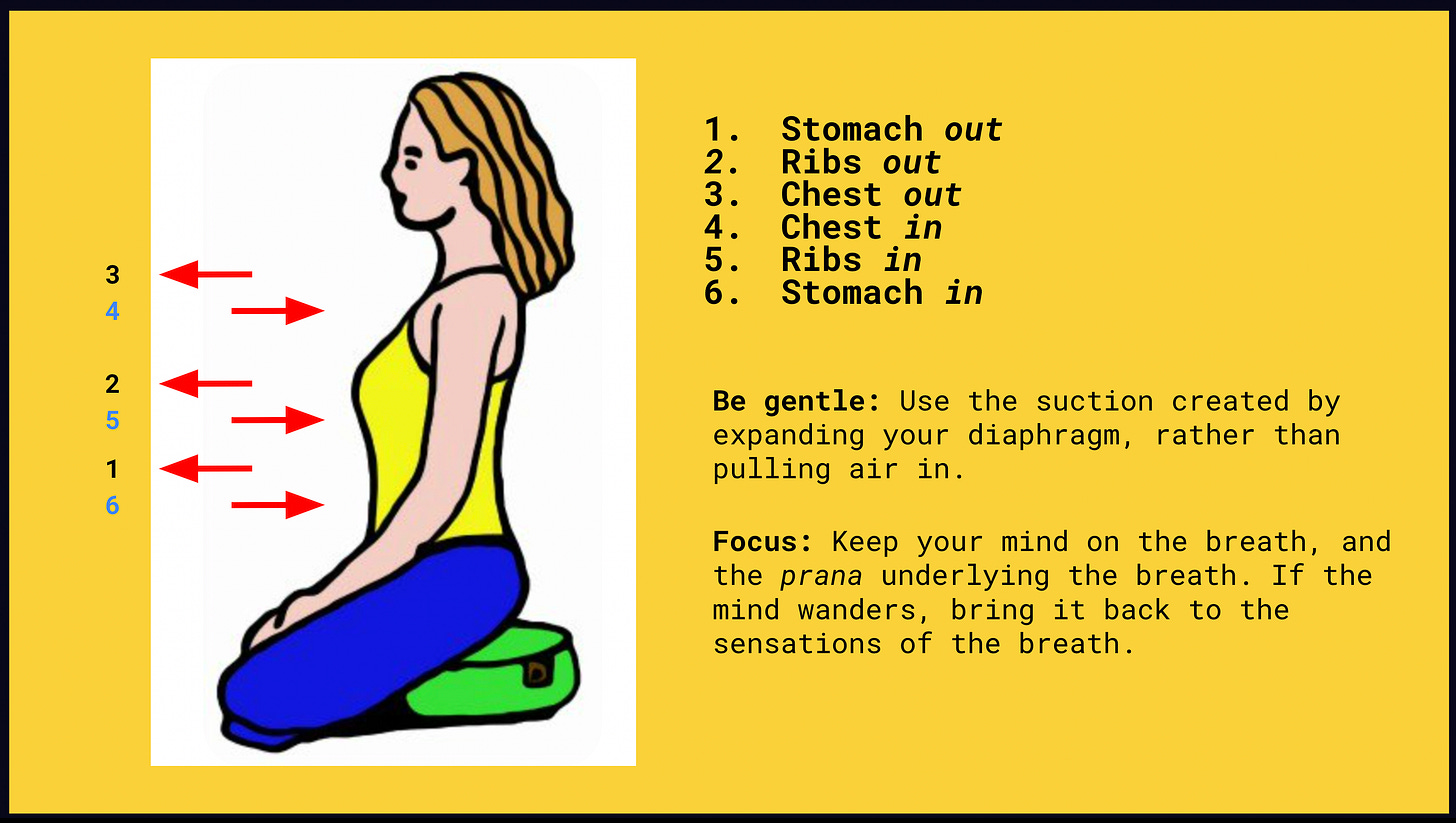

Rather than jumping into the steps mentioned in this diagram, start by isolating the stomach, ribs, and chest one by one. For all the steps, make sure to breathe in and out through your nose, keeping the lips closed and the tongue resting behind the top front teeth, on the roof of the mouth.

Step 1: Isolate the stomach. Expand your stomach outward as you breathe in, and contract the stomach inward as you breathe out. It should feel as though the movement of the stomach leads to the breath, rather than the other way around. As you expand the stomach, the breath should be drawn inward, and as you contract the stomach, the breath should feel like it is being squeezed out.

Step 2: Next, try to isolate the ribs, around the solar plexus (numbers 2 and 5 on the diagram). Expand the ribs and breathe in, and contract the ribs to breathe out. The stomach should not move.

Step 3: Finally, isolate the chest. Expand the chest outward as you breathe in, making sure to keep the stomach and ribs as still as possible. Then contract the chest as you breathe out.

Tip: If you are finding this difficult, try to visualize a point of light at the specific location where you are breathing. For example, when isolating the stomach, imagine a point of light at the belly button. When isolating the ribs, imagine a point of light at the solar plexus. When isolating the chest, imagine a point of light at the top of the sternum (where the chest connects to the neck in the front).

Alternatively, you can try to place your hand on each location as you try to isolate it, or lie down on the ground to feel the expansions and contractions more intensely, before shifting into your Aasana.

Try this a few times, isolating each area until you have gotten the hang of it.

Step 4: Once you have a good handle on each area by itself, try to bring them all together into a single coordinated breath:

Start by expanding the stomach

Expand the ribs

Expand the chest

Deflate the chest

Deflate the ribs

Deflate the stomach

First, make sure to be gentle. Do not force the air in. It should feel as though the expansion and contraction of the torso is the cause of the air moving in, not the other way around.

Second, identify your mode of practice. When practising this in your Aasana, breathe all the way in, and all the way out. However, when practising this as your everyday normal breathing, only fill the lungs about three-quarters of the way for the best results.

Finally, it helps to focus. Try to keep your mind on the subtle force by which you are breathing. If the mind wanders, simply bring the attention back to the breath.

Try it for 10 to 15 repetitions (steps 1 through 6 being a single repetition), and practice it every now and then. This is to become your normal breathing technique.

Once this starts to feel easy, then you are ready for the techniques that will follow.

Until next time:

Practice Deergha Shvaasam at least twice per day. If you have a regular meditation practice, try this as soon as you sit down in your Aasana, prior to meditation.

Set a timer for three to five times in the day. When the timer goes off, notice how you are breathing, and make sure to use this technique if you aren’t already doing so, filling your lungs about three-quarters of the way.

Take notes to see your progress over the course of the week, taking note of your mental state before and after the practice.

Next time: Fundamentals of Praanaayaam