How do I stop feeling this way?

The 9 Obstacles, 4 Accompaniments, and one-pointedness of mind

Om Sri Gurubhyo Namah. Salutations to all the teachers.

When we feel bored, dejected, anxious, frustrated or sad, our tendency is to look around for a cause outside of ourselves. Perhaps you’re watching a movie but you feel bored - the tendency is to say “this movie is boring.” Perhaps you feel a sense of general sadness or anxiety - here also, the tendency is to try to find the source. Maybe you feel “I don’t like my job, and that is making me sad” or perhaps “I am not as successful as I thought I would be at this age, and that makes me anxious” or “I hate this pandemic - I’m so bored sitting at home all alone and that makes me feel frustrated.”

Once the apparent source has been identified, we then make an attempt to solve the problem or change the situation in the hope that it will make us feel differently, often only to find ourselves in the same place where we began.

Notice, there is a common thread throughout these “negative” emotions of anxiety, sadness, frustration, etc. - a scattered mind. Usually, we think that the situations in our life lead to these feelings, and these feelings lead to a scattered mind. We assume that the source of the problem is an object of perception (the movie, the job, the idea of “success, etc.). We think we are distracted because the objects are somehow faulty, or not good enough to hold our attention. Further, with this assumption in hand, we run around trying to solve situations which are often outside of our control, or that take tremendous effort to solve, only to be disappointed when the feelings of sadness, anxiety, and dejection don’t go away.

Yoga turns this assumption on its head - the scattered mind is not the result, but the cause.

Over the past two weeks, we went over the twin foundations of Yoga - Abhyaas (Practice), and Vairaagya (dispassion). These two are to be kept in balance in order to effectively edit the tendencies in our mind towards peace and tranquility, regardless of situations that arise in our lives. However, in practice (pun intended), it is extremely difficult to remain disciplined over a long period of time.

We may start a meditation practice, keep it up for a few days or even weeks, and then stop. For some of us, we may even keep it up for several years but find it difficult to deepen the practice. Although this can often lead to frustration, it is completely normal - in fact, this phenomenon is explicitly discussed in the Yoga Sutras. Understanding these obstacles to practice and their accompaniments helps us to shine a light on how to break out of the “funk” that we may find ourselves in, and to prepare the mind for more advanced practices like meditation.

The underlying principle

We normally feel like the problems in the external world are the cause of our “negative” feelings like sadness, frustrations, and anxieties. Yoga clears up this confusion with a simple causal chain: obstacles result in scattering in the mind, and the scattered mind is the cause of “negative” feelings (also referred to as accompaniments, since they accompany the scattered mind).

We want to get rid of these feelings, but due to our confusion, we run around trying to solve the external problems. This takes our limited attention away from solving the underlying obstacles. As a result, while we may find temporary respite from the raging river that is the mind, it does not last.

Instead, if we make a habit of focusing the mind, we can break the chain between obstacles and “negative” feelings. With a focused mind, not only do the accompaniments disappear, but we also regain the energy needed to solve the underlying obstacles to a deeper meditation practice. The removal of the accompaniments is a nice side-dish, but the main course is the removal of the obstacles to Samadhi - meditative absorption, the last of the eight limbs of Yoga.

The 9 obstacles

These obstacles are the cause of gaps in practice, and block the Yogi’s progress towards the ultimate meditative stage of Samadhi. They are called “antaraayaah” (literally “that which causes a gap”). They begin as distractions, and if left unsolved, end up making it very difficult to maintain a steady practice of Yoga. They are:

Vyaadhi: Disease

Styaan: Mental coagulation/heaviness

Samshaya: Doubt

Pramaad: Carelessness

Aalasya: Sloth

Avirati: Desirousness

Bhraanti-Darshan: Misapprehension

Aalabdha-Bhumikatva: Inability to find a base

Anavasthitva: Instability/Inability to maintain a state

Vyaadhi: Disease

This refers specifically to bodily ailments. If you are physically unwell, it becomes very difficult to practice since the mind is focused on the discomfort in the body.

Styaan: Mental coagulation/heaviness

This is the disinclination of the mind towards work. According to Shankaracharya, it is a sort of mental paralysis that makes it difficult to act. The word styaan literally translates to coagulation, thickness, density, or oiliness, conjuring up the image of moving through thick oil in order to move even the smallest amount. This particular obstacle is different from laziness/sloth, mentioned below, in that it runs deeper. One may want to practice, but they cannot bring themselves to do it despite tremendous effort.

Samshaya: Doubt

There is a lot of discussion on doubt in Indian philosophy. Briefly, doubt arises when there is a lack of distinguishing characteristics between two things. The traditional example is when a person sees a tree stump in the distance at dusk, but is unsure if it is a person or a tree stump. As a result of this, the mind (specifically the manas) flits back and forth between the two (or more) options. In the context of Yoga, the Yogi may start to wonder if their practice will actually have an effect, whether their practice is doable or not, or even have unanswered questions about the underlying philosophy or practices. As a result of this unresolved doubt, the Yogi may stop practicing.

Pramaad: Carelessness

This one is especially common in today’s world, where we want to jump straight into meditation without the proper foundations. What we usually refer to as “meditation” is actually a mixture of the sixth, seventh, and eighth limbs of Yoga (more on the eight limbs later). What’s more, the eight-limbed practice itself follows several preliminary practices! Jumping directly into the deep-end results in frustration (e.g. I can’t sit still and meditate), dejection (e.g. I’m terrible at meditation), and eventually a break in practice.

Aalasya: Sloth

Aalasya is simply a lack of effort. Notice, it is similar to styaan (idleness) above - in both scenarios, the external perspective is the same - the person is not practicing. However, there is a subtle difference in the mind. In styaan, the person is as though mentally paralysed. They may genuinely want to practice, but find themselves unable to do so. This may seem like laziness from the outside, but actually is a much deeper issue. In aalasya, on the other hand, the Yogi simply needs to decide - there is no additional clouding that prevents practice except their unwillingness to act.

Avirati: Desirousness

Constant contemplation of sense objects and sense pleasures is another potential cause for gaps in practice. Note, there is no moral judgement here - this should not be read as “sense pleasure is bad.” Rather, it is simply a statement of fact - contemplation of sense objects and attachment to sense pleasures will result in gaps in practice. We often disguise avirati as “self-care” (the hedonistic kind) when actually we are just distracting ourselves. We can be deeply afraid to be with ourselves and our own thoughts, and so we grasp at the world as a method of escape. Following this tendency is avirati.

Bhraanti-Darshan: Misapprehension

Bhraanti-darshan (literally “seeing in error”) is where one might feel as though they have had some sort of experience, but actually did not, and so they think that they are further along than they are. For example, one might theoretically understand samadhi, and while in meditation, feel as though they experienced it. Or, one might have ideas about “out of body” experiences or visual phenomena that may occur through a deep meditation practice, and imagine (ie. vikalpa) that they have had those experiences. As a result of this misapprehension, the Yogi might feel like there is no longer a need to practice, or may attempt practices that they are not yet prepared for and thus feel dejected or frustrated. In this way, bhraanti-darshan can result in gaps in practice.

Aalabdha-Bhumikatva: Inability to find a base

We may hear of many different “types” of meditation - breath, body-awareness, sensory-awareness, Vipassana, Za-Zen, Yoga, mindfulness, Kundalini, Tantra, and so many more. What primarily differentiates these “types” is the support that is used for the mind - in Yoga, this is called the “aalambanaa.” When we constantly shift our aalambanaa - trying one thing one day, and another the next day - this does not allow us to go deep, and so is an obstacle to Samadhi (meditative absorption - the eighth and final limb of Yoga). Additionally, aalabdha-bhumikatva is classified as an obstacle because the Yogi’s continuation of practice depends on a superficial desire to try new things rather than the effects of bliss and calm that come from a deep practice. Once they have run out of things to try, or after not having achieved any results, the individual will feel disillusioned, and so stop practicing. We will discuss this particular obstacle in more detail when we go over breadth vs. depth of meditation.

Anavasthitva: Instability/Inability to maintain a state

The final and most subtle obstacle is anavasthitva - literally instability. This manifests as “glimpses” - the practitioner may have brief, momentary insights, but they are unable to maintain the state. While this may result in a desire to practice more, it can also lead to dejection and that can result in a break in practice.

The 4 Accompaniments

The obstacles themselves can be difficult to recognise directly. However, there are four signs that we can look for in ourselves that indicate the presence of an underlying obstacle:

Dukkha: Sadness/Distress

Daurmanasya: Dejection/Frustration

Angam-ejayatva: Anxiety (literally, trembling of the limbs)

Shvaasa-Prashvaasa: Irregular breathing

The obstacles (the 9 above) result in a scattering of the mind, and the scattered mind results in one or more of these four feelings (accompaniments). These are so easy to see that you can recognise them in another person - but don’t go around looking for these in others or diagnosing people! Everyone is on their own path. Not only that, but an external observer can only go so far as to see the accompaniments. The underlying obstacle is only perceptible to the individual themselves.

Take a moment to do a quick self-diagnosis. If you are unflinchingly honest with yourself, at the very least you can know what your accompaniments are, if not the obstacles themselves. So how do we get rid of these feelings? The practice of Yoga (the eight limbs, that is, including meditation) helps, of course. But the obstacles prevent you from practicing, so what do you do?

Eka-Tattva-Abhyaas: One thing at a time

Have you ever found yourself watching TV, with your laptop open, and your phone in your hand? Do you find yourself aimlessly scrolling through social media while listening to music? What about when you’re in a meeting but reading emails at the same time? This behaviour is the opposite of Eka-Tattva-Abhyaas (literally, the practice of one that-ness).

Eka-Tattva-Abhyaas means to place your entire attention on only one thing at a time. This means if you are watching TV, just watch TV. If you are “phone-ing” (yes, I just used “phone” as a verb), just “phone.” If you are listening to someone, just listen. If you are writing emails, just write emails, and if you’re in a meeting, just be in the meeting. This requires first noticing when you are automatically moving towards scattering your attention, and then intentionally focusing it by dropping away all other things.

To be clear, eka-tattva-abhyaas is not “just focusing.” It is a constant practice of bringing the mind back to one thing at a time - training the mind as one trains a wild horse. This can be extremely difficult to do.

At the root of this difficulty is a feeling that we must do everything all at once, otherwise we won’t get anything done. There are many solutions to this - creating to-do lists, prioritising your work, and setting reasonable expectations with others based on what you can actually do are a few of them. But notice, that for all of these, it requires a letting go (vairaagya). In order to focus on one thing, you must mentally let go of everything else.

Additionally, it requires a constant mindfulness of your mode of activity - simply notice when you are trying to do more than one thing at a time, and gently bring your attention back.

Don’t be hard on yourself, this scattering is a natural tendency of the mind - view it with amusement, as one would view a child putting their hand in a cookie jar.

Finally, focus is not a forceful act. If you try to force your mind, it will jump away like trying to hold tightly on to moving water with your hand. If this is your problem, it may be helpful to view focus as an act of releasing everything aside from the object of your attention. Don’t hold on to the object of focus, rather, release everything else.

If you find this difficult, don’t worry. This practice gets easier over time, and it also gets deeper. At first, it is as above - focusing on one thing at a time before moving on to the next. Eventually however, it enables a more visceral experience of life itself. This may sound pretty esoteric, but it’s actually quite simple.

If we are used to being in a mode of constant stimulation - context switching between multiple things at a time - we may start to notice that life feels dull and empty, as though the saturation is low, and as though things are hollow.

Now let us inquire - why might this be the case?

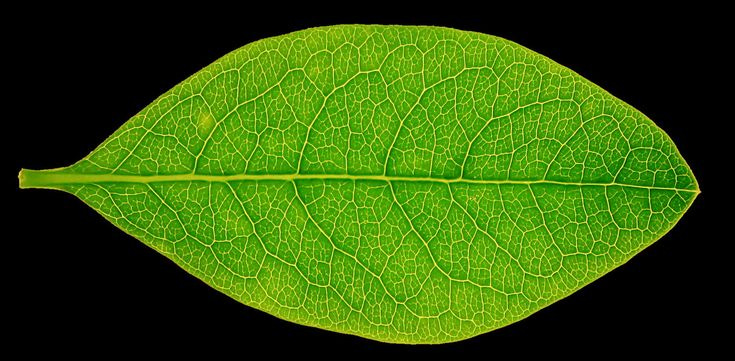

All perception is simply the input of information through the senses, into the mind. You get form (colour, brightness, shape, etc.) from your eyes, sound from your ears, and so on. Each object you perceive is a composite of many different micro-perceptions. For example, when you perceive a leaf on a tree, you perceive its shape, its colour, the lines on the leaf and their shape, maybe you touch it and feel a texture that differs along different parts of the leaf, or hear the sound of your fingers rustling along its surface. All these perceptions together are bundled up into the word “leaf.” Now when we normally see a leaf on a tree (perhaps we’re walking in a park, or down the street), we may notice that there are leaves on the trees, but don’t go into that kind of depth on each leaf. In the off-chance that we do notice the leaf, chances are that we will mentally label it “leaf” and move on to the next object.

Now the word “leaf” and the visceral experience of colour, texture, sound, and smell that comprise the actual object are two totally different things. The word is just a sound - a symbol for a rich multitude of micro-perceptions. By substituting the richness of the actual leaf for the word “leaf” we are substituting a high fidelity photograph for a stick figure.

Now imagine doing this for every object you ever experience. By not spending sufficient attention on objects, we end up living in a world of these “stick-figures”, and so it should be no surprise that we feel it to be hollow, dull, and unfulfilling. It is in this way that a scattered mind leads to the accompaniments.

To really bring this home, let us consider an example. Let us say you are eating a slice of pizza, watching TV, ruminating about something, and on your phone, all at the same time. You take a bite of the pizza, but your attention is now shifted to the TV screen. You start to settle into the dialogue on screen, but your attention shifts to your phone. Now you’re reading an article, but your attention shifts momentarily to your mental ruminations and then to the next bite of your pizza. In shifting attention between these objects, you are filtering out a vast majority of the information from each one of these experiences, and in doing so, not really experiencing any of them. If you live your whole life this way, you will feel unsatisfied and sad, like the world is dull and dreary, and as though there is nothing really to live for. On the other hand, if you were to focus on one thing at a time, and really take it all in, the world will go from grayscale to technicolour, and the accompaniments will simply disappear. Every object of experience will seem miraculous, beautiful, and fulfilling.

To quote the late great Alan Watts, “The menu is not the meal.”

By making a habit of acting this way - focusing on one thing at a time - one-pointedness (ie. eka-tattva-abhyaas) becomes a natural tendency. This is not just a seated meditation practice, but rather a lifestyle to be cultivated in every moment - on the cushion, off the cushion, and everywhere in between. It is something that anyone can do, regardless of level of experience or knowledge of Yoga.

Aside from providing relief from the four accompaniments, this tendency towards focus prepares the mind to be still for longer periods of time, enabling the practitioner to deepen their meditation practice.

One might wonder, why does this work? What is the mechanism? If you recall, the problem statement (ie. the cause of suffering) in the fourth Sutra was:

वृत्तिसारूप्यं इतरत्र |VrittiSaaroopyam ItaratraOtherwise, the Self becomes identified with the vrittis.

- Yoga Sutras 1.4

By focusing or sharpening the attention in this way, it is less likely to get entangled with the vrittis, as a sharp sword does not get entangled in vines but cuts right through them. As a result of less propensity for entanglement, there is less propensity for mental sufferifng. Additionally, over time, since we are not “serving them tea”, the vrittis themselves reduce, resulting in a lasting sense of peace and tranquility.

Until next time:

Throughout the day, notice when you are focusing on more than one thing at a time.

Gently bring the mind back to one thing, and give it your full, undivided attention.

Take notes on how you feel in terms of the four accompaniments, and see for yourself if this practice has any effect.

Next time: The Four Attitudes: Friendliness, Compassion, Gladness, and Equanimity

Brilliant article as always, Kunal 🙏

While reading about eka-tattva-abhyaas, I find myself remembering times when I become frustrated or angry while interacting with others. There seems to be a sense of the group's attention and sometimes others scatter that shared attention. Or maybe my wife and my kid are both asking for my attention at the same time. I'm at a loss for how to handle these situations with grace, when my intention is to focus on one thing at a time but I find myself in a situation where I'm unable to do so.

Curious to know your thoughts!